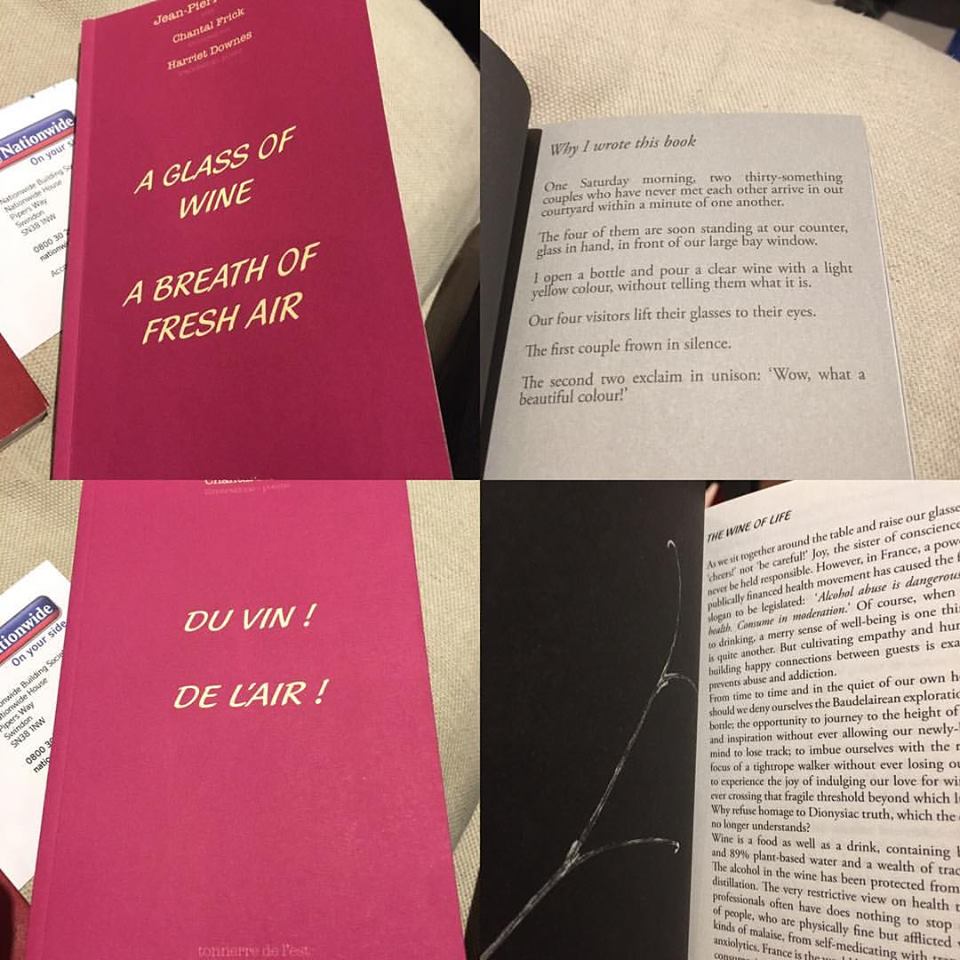

I was fortunate enough to attend a wine dinner at Terroirs Wine Bar hosted Jean-Pierre Frick who has written a book called Du Vin, De l’Air. This slim but beautifully-presented volume with illustrations by Chantal Frick, contains fascinating and provocative philosophical and political insights into the psychology of tasting, discusses what is real and natural, what is energy, what is biodynamics, what is terroir and appellation. Jean-Pierre is deeply invested in his local culture but also brings a wider perspective to bear, for he is not only a farmer, but also a scientist, a natural philosopher (invoking Goethe), and someone concerned for the future of man and the planet.

The book was apparently inspired by observing how different people react to the same wine. If we are what we eat, we are also what we drink, and how we appreciate wine indicates (to a greater or less extent) what our values are and the way we approach life. J-P sees various wine responses as emblematic of certain social and philosophic tensions. He implies that orthodoxies result from continuous classification and compartmentalisation. One may develop this further and examine how political systems are designed to make individuals confirm, and big corporations, by definition, view humans as consumers, cyphers to be conditioned to respond in a particular way. We need to encourage people to think of (and value) themselves as individuals, not to care what the majority thinks, and look inside themselves and to their feelings to guide their responses.

Frick begins his mini-thesis by describing two extreme types of taster: the academic and the adventurer. The academic, or professional, deconstructs wines on the basis of acquired knowledge. For them tasting is a matter of professional decorum, since they are tasting not just for themselves, but for knowledge itself, a knowledge that will be codified and organised and brought to bear at a later date. The adventurer, meanwhile, is intuitive; he or she prefers to sense the wine rather than judge it right or wrong. Normative values do not apply – the here-and-now is what matters, the very experience of tasting which excites the imagination and arouses the emotions.

Should you ever be “lucky” enough to sit on a wine tasting panel you will find yourself tasting in a virtual vacuum. No-one smiles, brows are furrowed in concentration, lips curled in contumely, the wine is viewed as an obstacle to be overcome, decrypted, evaluated, ticked off. No-one discusses what comes into their minds because it would distract everyone’s analytical attention. The panellist is not interested in just the wine’s colour, but in the very external quality of that colour, in other words its clarity (and thus preferred typicity), as opposed to the sensation that the colour engenders. The cultured taster exists to impose order on chaos and chaotic impressions. For this person, the wine must obey the archetype, the Platonic idea of an icily regular wine from that particular region, or this particular grape variety. The wine cannot exist as a unique living thing, with its own special energy and peculiar identity. It has to classified and defined. When we experience wine au naturel (as I like to call it), the wine and the context in which we experience it, draw energy from each other. Wines will inevitably taste better when the company is congenial and the food you want to eat /are thinking about, is on the table. This is logical; we are in a stimulating environment, our senses are vibrating positively, alive to nuance and energy. One may even say that we have love for what we are doing – drinking and taking pleasure in wine is surely a unifying experience.

As Christopher Hitchens in Hitch-22: A Memoir, observed:

“Alcohol makes other people less tedious, and food less bland, and can help provide what the Greeks called entheos, or the slight buzz of inspiration when reading or writing. The only worthwhile miracle in the New Testament—the transmutation of water into wine during the wedding at Cana—is a tribute to the persistence of Hellenism in an otherwise austere Judaea. The same applies to the seder at Passover, which is obviously modelled on the Platonic symposium: questions are asked (especially of the young) while wine is circulated. No better form of sodality has ever been devised: at Oxford one was positively expected to take wine during tutorials. The tongue must be untied. It’s not a coincidence that Omar Khayyam, rebuking and ridiculing the stone-faced Iranian mullahs of his time, pointed to the value of the grape as a mockery of their joyless and sterile regime. Visiting today’s Iran, I was delighted to find that citizens made a point of defying the clerical ban on booze, keeping it in their homes for visitors even if they didn’t particularly take to it themselves, and bootlegging it with great brio and ingenuity. These small revolutions affirm the human.”

And pleasure is a positive. Why should we deny ourselves, Jean-Pierre asks, the opportunity “to journey to the height of happiness and inspiration without ever allowing our newly-broadened mind to lose track. Why refuse homage to Dionysiac truth, which the digital man no longer understands?”

The book begins:

“Each of our individual cursors wavers between two caricatures.

As soon as a wine is poured, the academic is on mental high alert. They analyse it methodically according to a grid they have gradually acquired over the course of tastings. For example, they may have memorised a so-called typical colour for a given region or grape variety. If a colour is particularly intense, before they have even had a chance to smell the wine they may suspect it to be old or oxidised. The academic knows about different varieties, the classification of crus, the geology of various terroirs and the hierarchy of domains. Their language is codified and precise. They like to organise, arrange and file wines away in their memory cabinets. With the aid of numerous different readings, they possess the precise representation of a given appellation, and they like to encounter in a wine all of the characteristics that conform to their memory image.

The explorer, on the other hand, has rarely attended tasting lessons, opting to break away from such a structure. It is their senses that are alert, mental analysis takes a back seat. They find it easy to express their feelings; feelings evoked by colours, aromas and flavours, translated through a barely-codifed vocabulary and personal expressions of hyperbole. The language they use encompasses all of their perceptions at once. Some explorers describe physical effects: “This wine resonates down to the tips of my toes”, or “This wine is electric”. For them, the percentage of grape varieties in a given blend or the type of the soil on which they are grown is secondary to their experience of it. For the explorer, the wine evokes an atmosphere, a state of mind, encounters in other circumstances. Open to blind tasting, they spontaneously announce what they would like to cook or eat with the wine they are drinking.

The unusual and the unknown excite and delight them. Their appreciation of the wine will remain the same regardless of its appellation or price. Instead of filing it away inside their heads, they spend time thinking about which exact friends they would like to share it with. Discovery, astonishment and surprise take precedence over conventional points of reference…”

I believe we find these aesthetic oppositions in every facet of life. The academic or professional must be seen to rise above the fray; to have authority conferred upon them and be deferred to constantly, to be respected for an ability to filter out the subjective, and strangely enough, not to treat wine in the spirit in which it was made, nor the reason for which it was intended. Professionals may speak of certainties and inalienable wine truths, but to cast them as experts is to describe their influence rather than their superiority. When a wine is poured into the glass and sits there glinting in all innocence, all men and women are equal in terms of their responses. Wine should be about liberté, egalité and fraternité rather than critical hierarchy and rigidité.

Jean-Pierre also discusses the nature of perceived wine faults. Some faults are genuinely faults, others are not. Often wines are dismissed swiftly because they do not accord with the norm. If you are tasting dozens, hundreds of wines that are much of muchness, then the wine which is quirky or awkward, is easy to dismiss, precisely because it is (considered) atypical. If this proves anything it proves that one needs to spend time before sweeping to conclusions – a hedonistic wine drinker will take the time to allow the wine to reveal itself gradually. A wine may take up to two years “to be born” – if you add together the growing season, the fermentation cycle and maturation process – and then for a person to dismiss it for what it is not in an instant suggests a dysfunction in the critical process.

Wine responses involve a certain degree of complicity from the drinker. This involves a different aesthetic to the mapped response, and one which respects that wines are often the result of incidents and accidents, have edges and maculae, and where mutability is built into the wine itself.

Take oxidation. There are those who, looking at the colour of the wine will sum it up on the basis of “colorimetric prejudice” (Jean-Pierre). They doubt the integrity of wine which has an off colour. I have been surprised by wines so often; Jean-Francois Chene’s extraordinary O2 voile and fruit, Didier Barral’s (Faugeres) Blanc. These wines are not in the textbook– an expert’s nose would wrinkle reflexively before he or she dipped it towards the offending brown(ish) liquid. Those that respond in this fashion are truly judging by appearances, their responses conditioned by habit to find aromas, flavours and a balance that fully meet their expectation.

Winemakers also trade on expectation. Most champagne producers blend to a style, using dosage to correct and ameliorate and achieve consistency. Other producers may use simple aromatic markers such as new oak and yeasts to provide us with a sense of recognition, comfort and reassurance.

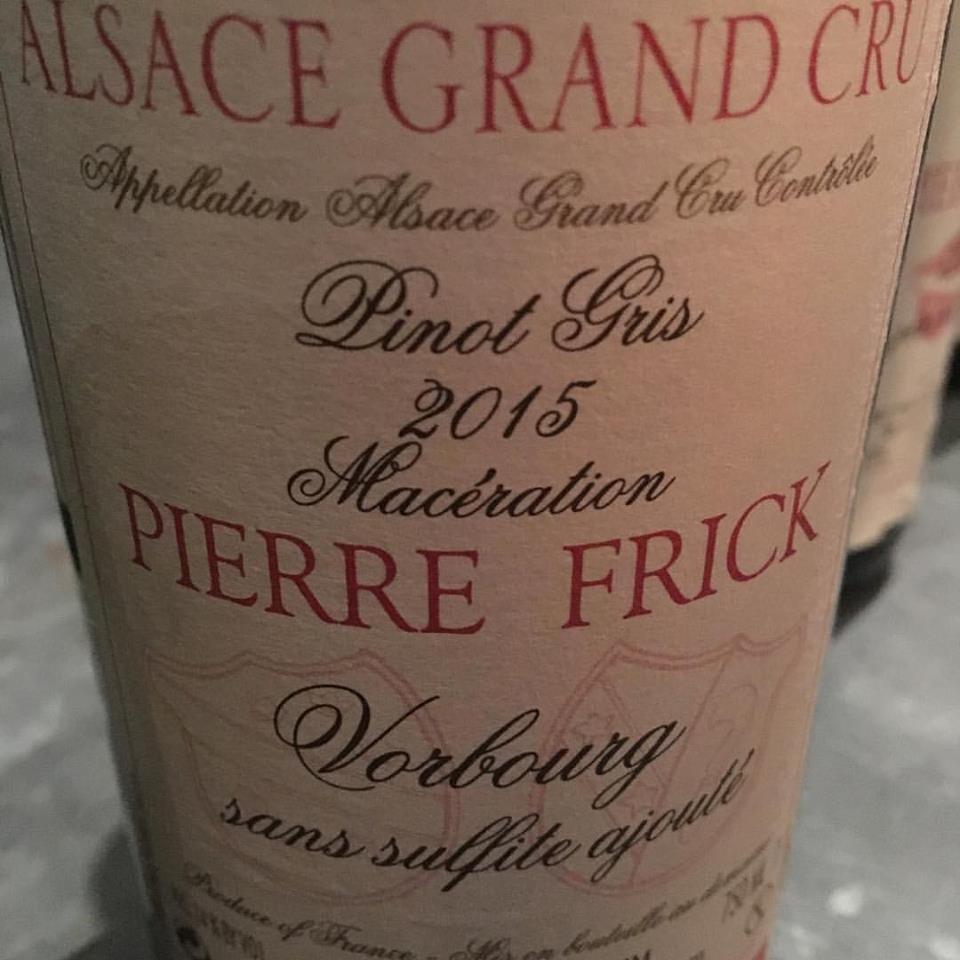

Yes, expectation colours perceptions of wine. When tasting a vin jaune, a sherry or a Marsala one is within a certain “umami-recognition-comfort-zone”. The oxidative clothes maketh the wine, so to speak. Even the aged white Rioja or the old-fashioned orange/mahogany-hued Châteauneuf-du-Pape will accord to preconceived views about how these respective wines might smell and taste. Encountered in other styles and grapes, however, the oxidative veneer strikes a discord, and the characteristic is judged as a fault. Examples here might be the aforementioned Loire Chenins, the foudre-aged wines of Pierre Frick (decried by a particular MW for whom anaerobic cleanliness is evidently next to godliness), and the terroir-specific Sancerres and Pouilly-Fumes of Sebastian Riffault and Alex Bain respectively, but it all rather depends whether you think this particular character is an unhappy superimposition or part of the very fabric of the wine. The “ox” presence divides the critics and sommeliers – Bettane’s attack on the so-styled tarnished wines of certain Loire vignerons exemplifies a kind of dour prescriptiveness that so afflicts the wine industry – his opinion right or right. You might just as well argue that super-controlled ferments, high sulphur regimes and myriad other interventions have falsified wines by allowing inferior vineyards to produce unnaturally polished wines. The results of winemaking should not always be invariably construed as good or bad, right or wrong, oxidised (boo) or clean (divine), but seen as the culmination of a series of complex aesthetic and practical choices.

The Shock of The Old

Modern palates find it difficult to cope with dissonant flavours in wines. Just as in music you may seek rhythm and melody, or meter and rhyme in poetry, or classical proportion in painting, so the brain naturally tries to channel aromas and flavours into familiar patterns and shapes. The role of the critic or commentator, meanwhile, is to describe and simplify, put wine into familiar contexts. Non-conformist wines and winemaking end is viewed as aberrant at best, and, at worst, beyond the pale. As soon as you confront certain people with something that is notionally blemished, say a Sauvignon that is almost amber in colour and has no obvious fruity aromatics, or tannins in a white wine when you are expecting clean and cleaned-up juice, they are disconcerted for they have been taught to believe that these are deviations from the norm. Such templates need to be shattered, otherwise we will live the mappined life, forever defaulting to the safest options.

To give a musical analogy, the dichotomy between tonality vs. atonality is a product of the changing perception of theory and harmony over the historical continuum – Chopin would be slightly atonal to Bach, and Bartok to Chopin. The same thing in jazz – Ellington would be atonal to Armstrong (slightly), Diz, Bird & Miles to Ellington, and Ornette Coleman to everybody. It’s a matter of what is considered conventional tonal harmony by the standards of the day. What is considered atonal music currently is the 20th century composers like Wolff, Berg, late Stravinsky, Hauer, Schoenburg etc. A lot of these composers used certain techniques and theories in the pursuit of atonality – whole tone, 12 tone, tone row, microtonal, Musique Concrete etc. It’s not just the composers – music can be interpreted and re-imagined by the performers. The same applies to winemaking – current oenological orthodoxies would not have been recognised 50 years ago. Grape juice is always about potential, and all about interpretation, which is why many winemakers love to experiment. And surely this is healthy. Barthes said that current opinion (which he called Doxa) was like Medusa. If you acknowledged it you become petrified.

The styles of wines they are a-changing and will continue to change. Some natural vignerons have chosen to uncouple themselves from the orthodox theories of cool ferment, closed vat, cultivated yeast because they feel that the wine cannot breathe in such an inert environment, and imprisoned by technical trumpery, will lose its soul.

A Wine is a Wine is a Wine

Many in the trade are in jobs where they are ultimately responsible to the end product user – a spade should therefore be a spade – a Sauvignon identifiably a Sauvignon – there should be square wines for square times. But not all drinkers are square.

It is also presumptuous (but it happens in all walk of life where critics critique) to believe implicitly that one knows better than the artisan-vigneron. Just like drinkers and wine critics, artisan winemakers are certainly not infallible, but their actions in the vineyard and winery determine the final individuated personality of the wine. And the wines are usually the way they are for many reasons. Decisions, such as topping or not topping up barrels, how much sulphur to use, to push for malo or not, to let fermentation take its natural course, in other words, all the physical choices of winemaking, will influence the development of the wine itself. For me, however, the paradigm of good winemaking is knowing when to step aside and leave the wine to its devices.

When I see the fault-sniffers, reduction hounds and oxidation haters reducing (no pun intended) wines to the sum of the aromas they’re not sure about, I know that wine tasting has become a cognitive demi-science and lacks an emotional, instinctive dimension.

The obverse of habit is surprise and discovery. It is liberating not to be confined by expectations, to be open to shock and awe. And not to have to judge. To experience the wine in a recognisably human context. The alternative, as Jean-Pierre says, is mummification.

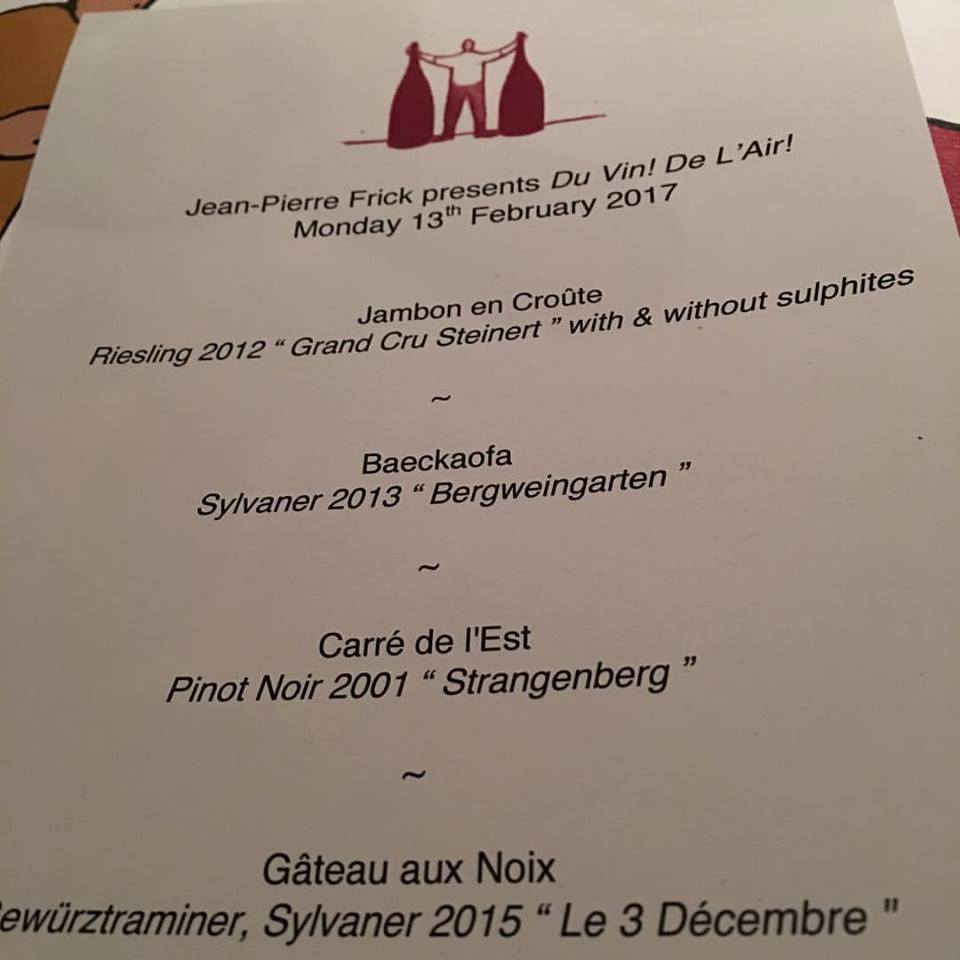

The dinner at Terroirs commenced with two Rieslings from the Steinert Grand Cru (2012 vintage). The grapes came from the same vineyard and the two cuvees were bottled a mere one hour apart. The only subtle difference is that one cuvee received around 10 mg of SO2 at bottling; the other was bottled without any addition. Jean-Pierre asked us to describe and assess the two wines. For me (and for most present) the difference was startling: one furiously energetic, taut, mineral, prickling over the tongue, the other more golden, softer, and more developed. It was as if the wine did not like the sulphur, the juice was shocked, the message muddled. Normally, opinions would be fairly equally split amongst group of tasters, but here, even people who didn’t identify which wine had sulphur added, vastly preferred the one which did not. I also realise that my palate prefers wines that taste liberated and natural. I don’t analyse the particular elements that bring this to pass– perception of acidity or ph, dissolved SO2, reduction etc; there is an almost imperceptible point of balance where the wine “feels” right – in and of itself.

Excellent article, so many valid points in my opinion. I have tasted on wine panels in France for medals and found it a truly joyless experience, whilst I bring knowledge to my tasting I want to be excited and enjoy the wines I taste. Most of us would usually be on the line between these opposites, sadly some seem to think that any acknowledgement of anything but a po faced approach is a betrayal of their self-appointed expertise.

Natural wines to me are a source of pleasure as well as philosophical satisfaction, they are capable of profundity as much as any wine. My most memorable wine moment in recent years was Casa Pardet’s Cabernet Sauvignon, one of those where your whole mind is captivated by what is in the glass.

Thanks for this article, it expresses so many of my own thoughts too.

Pingback: La Famille de Les Caves: A tribute to those near and dear: Part 1 – Les Caves de Pyrene