Biodynamic diversions

A Wreath of Sonnets, by France Preseren (one of Slovenia’s great poets):

Send but your rays their glory to renew

And let me not look for dawn’s light in vain

In your dear face, to hold back night’s domain

And calm the wildest storms that ever blew.

Fall with the load of heavy cares I knew,

Their fetters will be loosened, chain by chain,

And all the wounds they caused that still remain

With gentle soothing will be healed by you.

The cloud then from my frowning brow shall clear,

Within me hope will shine and thrive once more,

And from my lips sweet words again shall pour.

My heart no longer shall remain austere,

And from the inspiration in its store

Fresh flowers will spread fragrance far and near.

Zorjan is located in the hilly Tinjska Gora area of Slovenian Styria – this guy is virtually off the google search map, which, when one considers the quality and originality of the wines, is very surprising. Božidar Zorjan’s philosophy is that there is a sacred connection between land, animals, man and nature. He does not use any chemicals, his sheep have names and come running when he calls, and their only job is to fertilise the vineyard. He believes that animals belong on the land rather than in the stables– they are as free-roaming physicians, mapping and monitoring the rhythms of nature.

A former police inspector, and as far removed from the woolly jumper brigade as you can imagine, Božidar spoke at great length and with great erudition about the philosophies underpinning biodynamics. He reminded us that Steiner himself was a scientist rather than a farmer, although he was to invoke and then codify age-old farming practices based on observations of natural phenomena. Biodynamics, I suppose, looks all around by looking down (at the soil, at the farm an organism, at the human being at the apex of the farming activity, as it were, and at nature – and the earth – in a universal holding pattern. At the local organic level, there can be no synthetic chemicals or mechanical irrigation, anything which diminishes, dilutes or disrupts the natural order. A true biodynamic farm must also grow a variety of fruits and vegetables, and there should be animals, either domestic or wild, to keep this miniature ecosystem in check. A biodynamic farmer is one who listens and learns, takes his or her cue from the surroundings, ritually observes and works with rhythms of nature.

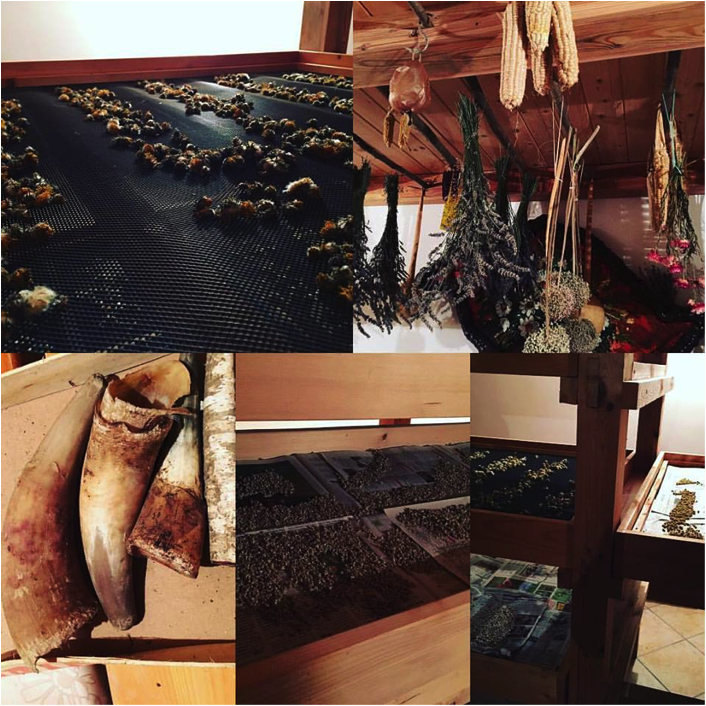

We are taken into a room dedicated to biodynamic preps. Yarrow and other floral extracts are being dried on wooden trays alongside beans, other plants and dried vegetables are suspended from beams and racks. Nothing is wasted; everything is done for a reason. We are shown some trays of grape seeds – these will be cleaned and pressed and made into the most delicious grape seed oil.

Delving deep into old historical texts Božidar has developed a “beyond-Steiner” holistic philosophy. What makes it attractive is how it incorporates every aspect of natural life into a single vision; it improves the quality of farming by putting the human into the natural equation.

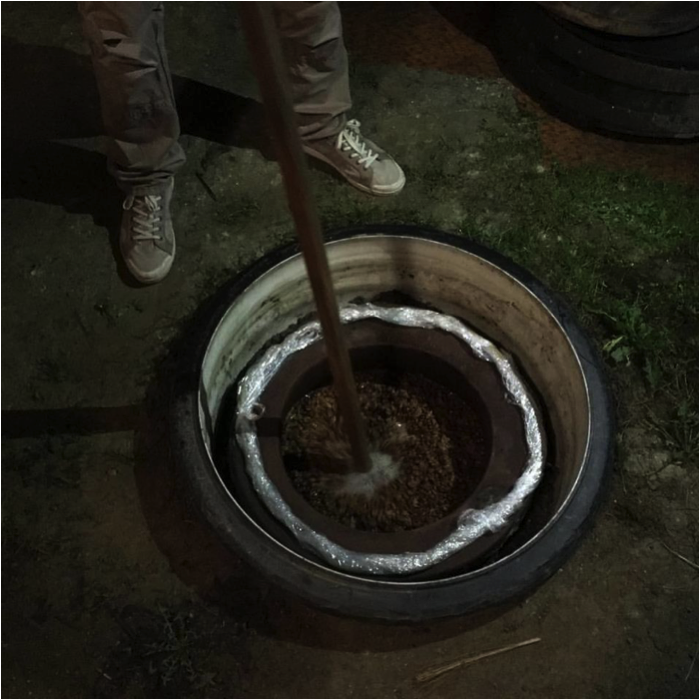

The vineyard glimpsed through the gloaming looks gorgeous, the wines are well… deep and nourishing. Winemaking, which takes place in the small cellar underneath the house, chimes with the nature of the farming. Božidar works with old Slavonian egg-shaped foudres as well as smaller barrels, and, interestingly, with small qvevri (brought back from Georgia in the early 1990s) buried in the open air just outside the house. He insists that not only must the wine have its feet in the soil but it should also be looking up to the stars (so to speak). One qvevri is opened and the thick crust of skins and pips is prodded with a long wooden pole. Marko dips his glass into the must and we swirl and crunch the grippy yet cooling liquid.

Back in the house we taste the wines with some swiftly conjured up salami, ham, cheese and sourdough bread. It is all fabulous – spending time in Slovenia with growers will turn you into a flavoursome lump of lard in no time. We mulled over the wines which were deep and unflashy. No one element stood out as you tasted – not the acidity, not the tannin, not a specific fruit character, not the elevage. They had structure and depth but in an all-in-one-way; they were fluid and harmonious and golden. You have to accept that you cannot always write tasting notes or push the liquid into a stylistic box.

Even glimpsed through a veil of mist Slovenia is a beautiful be-forested and be-mountained country with an excellent climate for vine growing. The farms tend to be small and consequently often have an integrated culture (making other products as well as wine – salamipalooza!). The border is notional around Goriska Brda and the Collio region; we are talking about the wider Mediterranean region rather than a high localised definition (or assessment) of Slovenian wines. It’s difficult to quantify quality off the back of visits to a few growers who are working in a progressively more natural idiom, but the vignerons we visited were so different that it suggests that anyone can make singular wine if they put their mind (and their heart) to it.

To paraphrase Valter Mlecnik, to become a better wine grower you need to trust to nature and simplify. We know from experience how difficult it is to make something that is pure and transparent in style. It requires a light (yet confident) touch, a kind of artful artlessness, beautiful grapes, sensitively handled.