Age shall not wither wine, except when it does…

Ah yes. And, oh no. The expression “this wine will age”, was considered a badge of honour, once upon a time. It was akin to saying that it is too serious and too profound for you – poor you – to understand it in its youth. That intense extraction, those unresolved tannins are, without doubt, a sign of latent charm and wisdom to come. Mere mortals with uninsured palates are not meant to comprehend the mysteries of ageworthiness and how beauty unfolds and Parker predictions pan out. Instead of the determinate “will age”, perhaps the more reserved “has the potential to age,” is closer to the mark.

The Ancient Greeks and Romans were aware of the potential of aged wines. In Greece, early examples of dried straw wines were noted for their ability to age due to their high sugar contents. These wines were stored in sealed earthenware amphora and kept for many years. In Rome, the most sought-after wines – such as Falernian – were prized for their ability to age for decades. In the Book of Luke it is noted: “No man also having drunk old wine straightway desireth new: for he saith, The old is better.” The Greek physician Galen wrote that the “taste” of aged wine was desirable and that this could be accomplished by heating or smoking the wine, though, in Galen’s opinion, these artificially aged wines were not as healthy to consume as naturally aged wines.

That a wine may qualitatively stand the test of time is somewhat trite in itself though. Some wines do indeed have beautiful material, are glorious in both their relative infancy and middle age, and make different kind of magic when they are older. The breast was delicious, the legs were equally good, and the bones made remarkably tasty soup. With certain wines, a tertiary quality may be rather wonderful, the aromatics almost tactile, and after that point in the evolution… comes decay and

Second childishness and mere oblivion

Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything

Zombie Wine & Vintage Beaujolais Nouveau

One has to investigate in each case, why different wines can survive a lengthy period of ageing. For example, once, on a visit to Styria, we were taken to a small cellar that still housed some bottles of co-operative wine made in the 1950s. And not by Cliff Richard. Here were yellowing liquids from Sylvaner, Muller Thurgau and so forth. Our cellar-cicerone, the Styrian grower, Franz Strohmeier, delicately eased the shrunken cork from a bottle with a mid-shoulder level and poured the amber-tinged wine into our outstretched glasses. Incredibly the wine had not oxidised. We took our glasses outside, lounged on the grass and chatted, taking an occasional sip of old gold. After half an hour, the wine had not moved a scintilla. Franz showed an entry from a book describing how the wine was made. Apparently, this one had 350 mg/l of sulphur. The wine was pickled, preserved in a state of chemical death; it was truly a zombie wine, and no amount of air could destroy it.

Do we mean that we are sure as sure can be, that in 10 years, the wine will metamorphose from ugly duckling to sainted swan? We hope this to be the case. Often it is not the case.

I doubt that the fine members of the co-op in Western Styria designed their 1955 Sylvaner intending it being stored, re-animated, assayed and assessed 60 years later. And I am fairly certain that the opinion or the effect on posterity (and beyond) is a secondary (or tertiary) consideration in any vigneron’s mind.

A further anecdote alert. In a similar vein (perhaps). Oz Clarke partnered a friend of mine in a cookery class for house husbands and home-aloners. At the end of each session, he would triumphantly bring out and open a bottle that he had brought from his cellar. On one occasion it was a Beaujolais Nouveau with around 20 years of bottle age. Stop smirking. All agreed that the wine – and it was still wine – was in cracking condition. Whatever the explanation for its exceptional longevity, this story illustrates that wine invariably has the capacity to surprise us. I have had a few serendipitous experiences care of some accidentally-aged bottles.

What are the criteria for a wine to age well?

Great grapes. As in cooking, good wine is so much about the prime ingredient. The quality of grapes depends in turn on the health of the vines, and how these vines are set up to maximise their potential. Deep root systems allow the vines to tap into the minerals and the abundance of microflora, further complexity may be achieved through environmental biodiversity. Practices such as good pruning technique, shoot thinning, appropriate canopy management, ensures that the maximum amount of energy in the vine is focused on ripening grape clusters.

Other things that contribute to potentially long-lived wines will be the nature of the vintage and how long the growing season is, the resultant thickness of the skins, natural acid in the grapes.

Harvest is critical, especially in timing and fruit selection. Often the best results are not achieved according to picking on the numbers, but tasting the balance between all the elements in the grape and intuitively knowing that the various components will help to create a harmonious wine in due course.

As we know, the quality of winemaking helps, or hinders. Oenology is a science, but it is equally an art. The numbers tell you one thing, your taste may tell you something different. Good quality winemaking involves capturing gently and accompanying the wine to its natural destination, not intensifying flavours for the sole purpose of creating a monumental wine.

What do we mean when we say that the wine will age? Sometimes, it is to remark at a particular time that the wine is currently immature and awkward. However, some men remain forever immature and awkward. Do we mean that we are sure as sure can be, that in 10 years, the wine will metamorphose from ugly duckling to sainted swan? We hope this to be the case. Often it is not the case. Things do fall apart, the central fruit core does not hold. The fruit may dry out, leaving only the hard tannins behind. The wine may also oxidise in that period of time.

And this will allow you re-enact the famous sketch in your best John Cleese accent:

Its metabolic processes are now ‘istory! It’s off the twig! It’s kicked the bucket, it’s shuffled off its mortal coil, run down the curtain and joined the bleedin’ choir invisible!! THIS IS AN EX-WINE!!

O Tannin Bombs

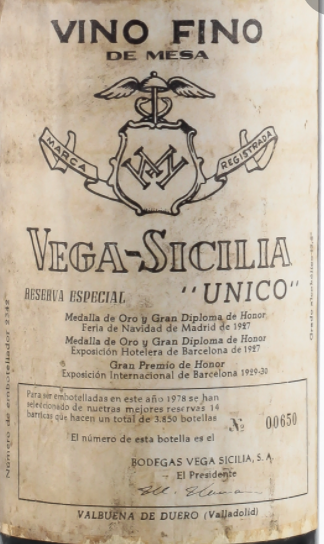

I once drank (a glass of)Vega Sicilia Unico. It was black as the proverbial, lacquered in oak, and tannic beyond belief. Even at 20 years and chump change, it was definitely not ready to drink. The wine is legendary and enjoyed a great reputation, but I was not sure on what basis that assessment was made. Is impenetrability per se a positive quality? Many wines have a similar capacity for opacity, but is not transparency is a greater quality and that the wine communicates something of itself, rather than remains in a state of mute muddled stubbornness. Some wines seem to be made to prove a point. Alain Brumont made a wine that saw 400% new oak. I spilled some of it on my hands twenty years ago and have been washing them ever since. The wine was monumental, architecturally magnificent, a gothic cathedral of wine, but one wouldn’t want to be entombed in it, so to speak.

Am I alone

And unobserved? I am!

Then let me own

I’m an aesthetic sham!

This air severe

Is but a mere

Veneer!

This cynic smile

Is but a wile

Of guile!

This costume chaste

Is but good taste

Misplaced!

Why, what a very singularly deep young wine this deep young wine must be!

In a sense, such wines are about pushing the envelope of extraction. Winemakers are entitled to experiment as they wish. The vogue for meta-structural wines has passed, however.

Nevertheless, there are some wines, rooted in a winemaking style, a place or a culture, and even in a particular grape variety that have the potential to age well.

In general, wines with a low ph (such as Pinot Noir and Sangiovese have a greater capability of ageing. With red wines, a high level of flavour compounds, such as phenolic (most notably tannins), will increase the likelihood that a wine will be able to age. Wines with high levels of phenols include Cabernet Sauvignon, Nebbiolo, Tannat and Syrah. The white wines with the longest ageing potential tend to be those with a high amount of natural extract and acidity. The acidity in white wines, acting as a preservative, has a role similar to that of tannins in red wines.

Slow-cooked wines & old timers

Here are some examples of wines that are either aged, achieve age or have age thrust upon them. In no particular order. The wines of Marsala, particularly the vergine styles pioneered by Marco de Bartoli. The Vecchio Samperi Ventennale, for instance, made by solera method of fractional blending until it achieves an average age of twenty years, is an astonishingly complex, powerful and resilient wine. The Vernaccia di Oristano of Sardinia (Attilio Contini’s, in particular) is another solera wine and is a sticker rather than a twister, and then, of course, sherries themselves will live a lifetime. These wines may derive their miles-on-the-clock in the cellar, but continue to perform at a high level for years to come. After 40-50 years all these wines taste like liquidised mahogany.

Not that wine has to go through a solera to attain semi-immortality. Controlled oxidation and lengthy elevage are responsible for some wines that can happily age half a century. Here we think of the Vin Jaunes of Jura and other sous voile wines that have spent years under a layer of flor.

What of wines that are not the result of these slow cooking techniques? I once served a 1945 Mazis-Chambertin from a negoce house. Its colour was incredible, the aromas boomed out of the glass. Either the vintage was concentrated beyond belief, or the wine had been creatively spiked with some darker liquid, Rhone Syrah, for example.

1961 Borgogno Barolo. Having purchased a chunky parcel 50 years after the vintage, we drank this wine with pleasure for a few years. It was barely in the tertiary phase, a testament to good quality fruit, very lengthy elevage and excellent storage (corks were replaced at regular intervals).

I have recounted on other occasions my various encounters with vintage Bourgueils from Domaine de la Chevalerie, and Chinons from Jerome & Alain Lenoir and Patrick Corbineau.

A 1972 Bourgueil (supposedly a lousy vintage) that seemed to gain colour and concentration in the glass, a 1979 Chinon that was graceful and floral and also gathered weight and tannin. These are the sort of wines that make you want to get out the Ouija board to summon up the spirit of Emile Peynaud to ask him how it is that old wines exposed to oxygen can acquire greater intensity. All these wines had been superbly looked after in their original cellars. They had not been moved for decades.

I once tasted some very old Shiraz with Charlie Melton and David Gleave. Old, as in back to the 1950s and 60s. From memory, the wines were more in the traditional self-effacing Syrah-style, weighing in at an 11% – 12% – and sans the new oak veneer. They were bonny in the extreme, still brilliantly alive and fresh. In fact, the wine world is replete with anecdotes about wines that were forgotten for decades, discovered, and opened and found to be in perfect drinking order. The past in wine is another country and that can be a good place to be.

Crusty old Rioja has the longest plateau of all of advanced maturity. That familiar smell of beeswax-buffed furniture in an old library. What imbues these wines with their capacity to age, is surprisingly high acidity.

Another anecdote. I am about to attack a bottle of Chateau Margaux from the mid-1950s with my corkscrew. I had been asked to decant this fabled wine for a table in a bistro (they were all eating Caesar salads) and had positioned myself for this delicate task in a stupid location, namely adjacent to some swing doors to the restaurant kitchen. Every time I raised the bottle to the neck of the decanter with a mixture of reverence and apprehension, a door would swing open violently and bang against my elbow causing the bottle to jerk and precious liquid to be jettisoned over the waiter’s station. This happened on at least three occasions. The Margaux, liberated after 40 years, was a nosegay of young blossom, the colour purple, in colour and in smell. I didn’t need to taste it to reassure the Caesar salad munchers that it was sublime – they didn’t care anyway. I dipped my forefinger in the plentiful liquid that had never reached the inside of the decanter. And it was good. No use crying over spilt aged Margaux.

On the other hand, Bordeaux bibles will tell you to consign certain labels from certain vintages to the oubliette and subsequently bequeath them to your grandchildren on their 18th birthdays. It is worth taking this advice with a healthy pinch of sediment. Ageing wine is a form of Russian roulette.

Time changes everything; its whirligig brings its revenges for wines that are unable to stands its test; equally it can transform certain wines into something more complex.

Hindsight may be a wonderful thing, but foresight is more wonderful. 80s red Burgundies were lauded to the skies at the time; so many collapsed under the weight of oak, extraction, over-maceration and alcohol. Also in Burgundy, premox accounted for the early death of many top white wines in the mid-1990s.

Ever since I have been in the wine trade, people have obsessed over vintage. Some people will write off a wine without even trying it, because the vintage is not a fashionable one. A great vintage is seen as a year in which the wines have greater value and that is often to do with their perceived greater ageing potential. Yet often the reverse it true. The circumstances that give the wine its spine may be found in smaller cooler vintages; the often-meretricious wines made in hot and sunny vintages fall apart sooner than we might imagine.

Is the purpose of ageing to resolve an imbalance, to discover the highest point in the arc of development, to see what happens to wine over a lengthy period of time (assuming that is stored decently) or because the drinker actually likes the aromas and flavours of tertiary aromatics? It can be any of these things.

Time changes everything; its whirligig brings its revenges for wines that are unable to stands its test; equally it can transform certain wines into something more complex. It is not time that does this, of course, and one must always look to the character of the wine itself for evidence of its ability to change for the better.

A great read all the way to the end. I like the Cliff Richard addition.