Read Chapter One Parts One, Two and Three

Chapter Two Parts One, Two and Three

Chapter Three Part One and Two and Three

Chapter Four Part One and Two

Chapter Five Part One

Wine diamonds

- What’s that in the bottle?

- It looks like slivers of glass.

- More like a disco glitterball light show!

- It’s like diamonds dancing in a cloud of purple smoke!!

- Tartrates are a normal by-product of wine as it ages—but, if the wine is exposed to temperatures below 5c, wine diamonds can form within one week of a wine bottle’s exposure to extreme temperatures. It is these chilly conditions that make the tartaric acid compounds in a wine naturally combine with potassium to form a crystal.

- Boring!

- What a tosser!

Outside London: The Stirrings of a UK Wine Culture

Is there a disjunction between London and the rest of the UK in terms of wine taste? Although I am mainly interested in regional attitudes towards natural wines, one may broaden the terms of reference to include all interesting, authentic, terroir-driven wines, unusual styles, and offbeat grape varieties.

We begin once more with that c-word. A character in Hans Johst’s play, Schlageter, opined: “Whenever I hear the word culture I reach for my gun”, although I prefer to recall the adaptation of this quote pronounced by a producer in Jean-Luc Godard’s 1963 film Le Mépris, who says: “Whenever I hear the word culture I take out my chequebook”.* A wine culture should never be pretentious or elitist or revolve around money; rather it should be endemic, with drinkers who are relaxed and curious about wine. Whilst more people than ever are drinking wine in the UK, we still seem to be unduly exercised by perceived trends, and how others regard our wine choices. That is not wine culture.

*The character in Schlageter actually says: “Whenever I hear the word culture, I release the safety catch on my Browning.”

Some people like to believe that an adventurous wine culture is synonymous with the easy availability of wines from the non-classic regions and countries. The origin of wine, however, means a lot more than simply the place where it is manufactured. After all, about thirty years ago, Bulgarian and Romanian wines positively (negatively) populated the shelves of supermarkets, hitting certain key price points (the result of cheap labour and industrial farming practices). Of course, in those days, a Bulgarian £3.99 Vatted Merlot was hardly representing a rich eastern European wine heritage. And nowadays, you may well be able to find wines from Brazil, China, Croatia and Georgia and other seemingly far-flung and exotic places, but in the majority of cases these are bland facsimile varietal wines made by oenologists as “products for a purpose”.

I have done enough wine events to know that by opening people to new taste sensations, you can help to change their attitudes towards wine.

To all intents, this is simply repackaging the same wine-taste (cold-fermented, filtered whites, for example, or reds manufactured with added tannins and chemical flavourings). It is not about the nuances of grape varieties either. Not only are international grapes made to a formula (by adding yeasts), so that they might derive from any country or region with a suitable wine facility, but indigenous varieties are also neutralised, so they neither reflect terroir nor vintage, but are a construct that may be always easily replicated to be instantly recognisable to the so-called average consumer.

This commercialism is not so much a gateway to more interesting things, as a revolving door to the same taste profile.

The common denominator approach to winemaking exists to create brands. Austria is associated with a single grape, Grüner Veltliner (brand Grüner), much as Italy used to associated with Pinot Grigio, and Argentina with Malbec. Yet so many commercial Grüners are heavily filtered, and are thoroughly anodyne as a result. This results in a vicious circle: people will buy Grüner because they believe that it is the great Austrian specialty, meanwhile producers in Austria will continue to make the style that they believe consumers can relate to. This commercialism is not so much a gateway to more interesting things, as a revolving door to the same taste profile. A commercial Fiano that tastes like a Côtes de Gascogne, or a white Verdejo, is offering three different countries and three different grape varieties in name only. The name of the wine, the country or region, the variety, is so much less important than the nature of the wine itself in terms of gauging how tastes are changing, or developing.

My perception of a so-called wine trend is really a gut feeling based on the sales of wine companies, what I’ve seen on the wine lists of mover-and-shaker-bars-and-restos, glimpsed on the shelves of interesting independent retailers, and by regular trawling through social media. It is not a scientific approach, but statistics shed less illumination on the aesthetic responses to wines than on quantitative measurements of buying and consumption.

From what I gather anecdotally, you’re less likely to find natural wines, skin contact/orange wines, organic wines from small artisan producers (say) outside London, because consumers are inherently more conservative outside the Metropolis. Does this perception hold water, or is it a generalisation? Individuals, after all, do move from place to place for work, others visit interesting wine regions, and attend major artisan wine fairs like Real Wine, RAW, La Dive, Les Anonymes, Villa Favorita etc. in order to broaden their wine horizons. More than happy to engage and educate rather than kowtow to perceived taste, these people will always try to find an audience for their love of unique artisan wines, even if it means, at first, swimming against the tide. The flipside is the restaurateur or sommelier who says: “My customers would not like this/these wines.” (How often have we heard that?) Claiming knowledge of a customer, and his or her taste, is presumptuous. Certainly, if you are unwilling to engage, and will only give people what you think they want, they will, of course, default to the tried-and-trusted. We should never talk about “archetypal consumers” as that reduces individuals to the status of cyphers. I have done enough wine events to know that by opening people to new taste sensations, you can help to change their attitudes towards wine.

Wine culture throughout the world may be concentrated in large cities (critical mass etc), but there are always demographics within demographics. You may have the opportunity to drink exciting, unusual authentic wines in London, but only in certain parts of town. East London, Central and SE London have become de facto wine destinations, whereas in other parts of London there is a comparative dearth of places to drink interesting wines. The reasons for this may be to do with the profile of the local inhabitants (age range, disposable income, nature of businesses in the area).

Outside London, cities like Bristol, Brighton, Manchester and Leeds may have the demographic ingredients to support a progressive wine culture, but for all that, it is down to individuals to make that leap of faith, and open a wine bar, not as a local oddity, thereby excluding certain people, but to ensure that any gastronomic enterprise is vibrant and inclusive, and that the service of wine is both friendly and informative. It is not so much that if you build it, they will come, but that Rome wasn’t built in a day. Wine trends are here today, gone tomorrow; real wine culture has roots.

A few years ago, Hammersmith, Chiswick and Shepherd’s Bush had a number of wonderful gastropubs and restaurants run by individuals who assembled interesting wine lists featuring bottles that they enjoyed drinking. These areas have changed; many of those establishments have since been sold and purchased by high street chains. Those wine lists now feature brands, and bland commercial wines. In East London, meanwhile, wider “craft culture” has exploded, with myriad bakeries, micro-breweries and distilleries fuelling a young artistic/bohemian community. There is an energy and excitement about food and booze around here; it is not simply, as the social caricaturists would have it “a hipster phenomenon” – although there is an element of certain people wanting to advertise themselves through their food and wine choices – it is that there is a community of people who love to explore new tastes, care about the provenance of ingredients (and wines), and enjoy talking about food and wine.

Wherever there is a healthy debate about food, you will probably find the stirrings of an informed wine culture. We must always return to this: wine is so much more than the label, or the perception of the product, or the adherence to a trend. It is the story inside the bottle. The more opportunity that people have to drink (and enjoy) real artisan wines, the more they will be creating a wine culture of their own.

Mattia Bianchi, who founded Berber & Q in Haggerston and then opened Shawarma Bar in Exmouth Market, organises a now-annual event called DIRT. It has a twofold purpose – firstly, to explore how flavours in – and feelings about – wine may be determined by soil type and micro-climate (Alice Feiring’s The Dirty Guide to Wine being an inspiration here) and secondly, to promote debate, banter and a greater awareness of those individuals who are communicating intelligently and passionately about wine:

I think there’s plenty bubbling under with a lot of sommeliers taking risks and approaching their wine lists in a more creative and ‘no-rules’ way. That’s why I’m throwing DIRT.

The issue is not with wine-dedicated places, where you already have a lot of knowledge amongst a team that is doing their job extremely well.

Some restaurants, which are not wine destinations, should be more creative in order to generate that sort of interest and fun within their wine lists.

I’m now seeing more guests taking greater risks with their wine choices. It’s fun to see this development.

We’ve got a fun job and we should introduce that sense of fun into our customers’ wine experience.

Events, dear boy, events

Terroirs has screened movies such as Jonathan Nossiter’s Natural Resistance and Skin Contact: Development of an Orange Taste (Bottled Films), hosted no fewer than four Georgian supras, witnessed guest chefs taking over the stoves with one particularly epic natural international wine bar mash-up featuring Melbourne’s Embla, Paris’ Le Verre Volé, Barcelona’s Bar Brutal and Brooklyn’s Four Horsemen; played host to hundreds of great vignerons in pre-and-post fair parties on behalf of Real Wine and RAW, conducted themed weekly barrel tastings, individual growers’ takeovers…

I once walked into Terroirs and saw managers and sommeliers from three top West End restaurants seated on different tables drinking wine and nibbling terrine(s), having snuck out of their own establishments for a swift refuel rather than come for a full-blown dinner.

In an increasingly crowded wine world, Terroirs has had to reinvent itself to stay relevant. Food and wine may be fuel, but eating out is an also an entertainment. Almost as soon as it opened and started receiving positive, even gushing, critical acclaim, customers queued to get in, not to sit down (no chance of that), but to squeeze into cramped standing areas for the sheer privilege of taking a glass of wine and some cheese or charcuterie. These were rollicking, stack-em-high times. The trade especially adored Terroirs. I once walked in and saw managers and sommeliers from three top West End restaurants seated on different tables drinking wine and nibbling terrine(s), having snuck out of their own establishments for a swift refuel rather than come for a full-blown dinner. Heston Blumenthal, Angela Hartnett and Pierre Koffmann, amongst other great chefs, came to sup the wares. In these moments, I thought Terroirs had achieved institutional immortality.

It was always our intention that Terroirs should be about more than eating and drinking well. It should also be a meeting-place, one where one might encounter a vigneron pouring his or her wine, or to have the opportunity to have dinner with one of the “heroes” of the natural wine world.

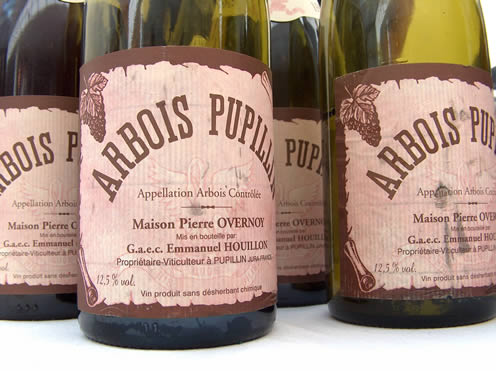

When Overnoy/Houillon Came to Terroirs

Most wine dinners, in my experience, are formal affairs, gilded with glistening glassware, lush napery and suffused with an air of commercial rapture. There’s more to gastronomy than table furniture and awe; geniality and generosity are what makes an occasion worth savouring.

This was undoubtedly a generational affair – Pierre Overnoy, who rarely ventures outside his native Pupillin alongside Emmanuel Houillon, with their family and friends – from the paterfamilias to the six-year-old on her i-pad. It was a privilege for us – not only because the wines are so desirable, although they possess the value of rarity (if that has value), but because to welcome Pierre and Manu, who are true artisans, humble to a fault, into our restaurant, to offer in return the hospitality that they offer to us when we visit, then that is what makes this job special. For the wines are what they are – sans maquillage, edgy, flawed, sensitive to the vintage, deeply rooted in their place. And that is their glory. They are living wines also, and thus constantly surprise you. Both Pierre and Manu speak self-effacingly about the wines – you feel that you should no more judge a certain wine by an absolute standard than you would judge a loaf of sourdough bread after it has come out of the oven (Pierre is a master baker so this analogy has legs!).

Chef Michal prepped a five-course dinner to match with eight wines, four of which were brought over by Manu and Pierre. Michal proudly emptied many a clavelin of vin jaune into his terrine and trout dishes to lend some vinous corroborative verisimilitude to gastronomic narrative! The food was upfront and hearty; the wines conversely creep up on you unannounced. I find that they resist easy descriptors; sure, they evolve, but oh-so slowly. It may be that they reach the ideal temperature in the glass or that they react favourably with a certain amount of oxygen or that the outer shell melts to reveal an inner core. The Savagnins and Chardonnays have the shell of reduction, then the veil of lees contact disperses, the fruit is “yellowing”. You don’t feel the acidity at the front of the mouth, which you do with the more driving Ganevat whites, for example. Here the acidity is somewhere in the middle of the mix, where warmth and minerality mingle.

It was a privilege to welcome Pierre & Manu en famille to Terroirs. Pierre had even had a mini-stroke the previous week, but nothing was going to prevent this old soldier-vigneron-baker from coming over to London.

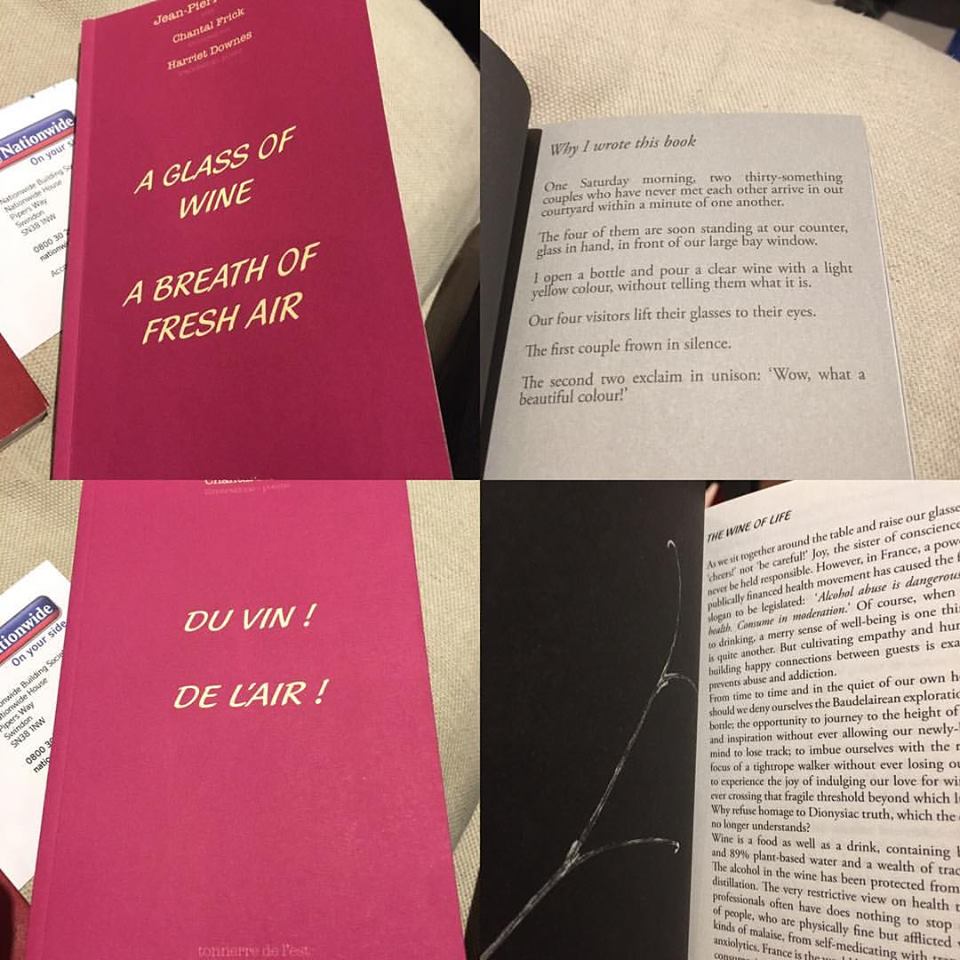

I was equally fortunate enough to attend another Terroirs wine dinner hosted by Jean-Pierre Frick who had written a book called Du Vin, De l’Air. This slim but beautifully-presented volume with illustrations by Chantal Frick, contains fascinating and provocative philosophical and political insights into the psychology of tasting, discusses what is real and natural, what is energy, what is biodynamics, what is terroir and appellation. Jean-Pierre is deeply invested in his local culture but also brings a wider perspective to bear, for he is not only a farmer, but also a scientist, a natural philosopher (invoking Goethe), and someone concerned for the future of man and the planet.

The book was apparently inspired by observing how different people react to the same wine. If we are what we eat, we are also what we drink, and how we appreciate wine indicates (to a greater or less extent) what our values are, and the way we approach life. J-P sees various wine responses as emblematic of certain social and philosophic tensions. He implies that orthodoxies result from continuous classification and compartmentalisation. One may develop this further and examine how political systems are designed to make individuals confirm, and big corporations, by definition, view humans as consumers, cyphers to be conditioned to respond in a particular way. We need to encourage people to think of (and value) themselves as individuals, not to care what the majority thinks, and look inside themselves and to their feelings to guide their responses.

Frick begins his mini-thesis by describing two extreme types of taster: the academic and the adventurer. The academic, or professional, deconstructs wines on the basis of acquired knowledge. For them tasting is a matter of professional decorum, since they are tasting not just for themselves, but for knowledge itself, a knowledge that will be codified and organised and brought to bear at a later date. The adventurer, meanwhile, is intuitive; he or she prefers to sense the wine rather than judge it right or wrong. Normative values do not apply – the here-and-now is what matters, the very experience of tasting which excites the imagination and arouses the emotions.

When I see the fault-sniffers, reduction hounds and oxidation haters reducing (no pun intended) wines to the sum of the aromas they’re not sure about, I know that wine tasting has become a cognitive demi-science and lacks an emotional, instinctive dimension.

The obverse of habit is surprise and discovery. It is liberating not to be confined by expectations, to be open to shock and awe. And not to have to judge. To experience the wine in a recognisably human context. The alternative, as Jean-Pierre says, is mummification.

The dinner at Terroirs commenced with two Rieslings from the Steinert Grand Cru (2012 vintage). The grapes came from the same vineyard and the two cuvees were bottled a mere one hour apart. The only subtle difference is that one cuvee received around 10 mg of SO2 at bottling; the other was bottled without any addition. Jean-Pierre asked us to describe and assess the two wines. For me (and for most present at the wine dinner) the difference was startling: one furiously energetic, taut, mineral, prickling over the tongue, the other more golden, softer, and more developed. It was as if the wine did not like the sulphur, the juice was shocked, the message muddled. Normally, opinions would be fairly equally split amongst group of tasters, but here, even people didn’t identify which wine had sulphur added, vastly preferred the one which did not. I also realise that my palate prefers wines that taste liberated and natural. I don’t analyse the particular elements that bring this to pass– perception of acidity or ph, dissolved SO2, reduction etc; there is an almost imperceptible point of balance where the wine “feels” right – in and of itself.

This was a revelation.

Someone will purloin a copy of the wine list and demand our most closely-guarded natural wine treasures. Towards the end of the evening there will be much bad dancing (and falling over). Some Georgians will burst into polyphonic song.

Terroirs’ eve-of-Real Wine Fair growers’ parties have added lustre to its legendary status. Around two hundred vignerons and their partners from a twenty or so wine-producing countries, spread across two floors of the restaurant and spilling out riotously onto the pavement. Tables are pushed back and will groan under a buffet of oysters, mounds of fatty rillettes, salads, and trays of slow cooked meat-and-bean stew. There will be bottles (usually magnums) everywhere with everyone clamouring to try everything. After a refreshing beer or several. The guys behind the bar will activate every crazy-shaped decanter in the house for some degustation aveugle. Someone will purloin a copy of the wine list and demand our most closely-guarded natural wine treasures. Towards the end of the evening there will be much bad dancing (and falling over). Some Georgians will burst into polyphonic song. Christophe Rohr will appear with his accordion and squeeze out uproarious renditions of everything from French folk ditties, to Abba and AC/DC. Brendan Tracey will belt out some punk anthems on his knees. There will be an attack of the Poire Cazottes.

Benoit, great lunch. Can we get another bottle of Chiroubles?

Before the attack of the Cazottes Poires!

–Snowed Under, Mimi, Fifi & Glouglou, Michel Tolmer

Alfred Prufrock measured out his dreary life in coffee spoons. We have measured out ours in a planet’s weight of terrine and rillettes, draining a small ocean of Houillon and Ganevat all the while, and hoisting the white flag on countless occasions ahead of the onslaught of the Cazottes Poires. And the 72 green tomatoes! “Meet you for a quick bite at lunch” now means to unbuckle your belt and strap in for the lengthy gastronomic duration – I am sure that the bar stools have a layer of superglue on them, as it seems impossible to detach oneself once the feeding and drinking process has begun. At least in my case. Many is the time I have gone for one glass of vino and ended up sashaying out of the restaurant through the pre-theatre crowd, exhaling naked eaux de vie fumes. Terroirs is a place to relax when one hasn’t got a second for oneself, especially when one is snowed under, and, indeed, absolutely drowning in work.

To be continued in Chapter Six…