Read Chapter One Parts One, Two and Three

Chapter Two Parts One, Two and Three

Chapter Three Part One and Two and Three

Chance rules our lives, and the future is all unknown. Best live as we may, from day to day. –Oedipus Rex, Sophocles

Destiny doesn’t do home visits…you have to go for it yourself. –The Prisoner of Heaven, Carlos Ruiz Zafón

Side effects of using the Infinite Improbability Drive include temporary (and sometimes permanent,) changes to environment and morphological structure, hallucinations, and the calling into being of large marine mammals. An incredible range of highly improbable things can happen. Known effects have included the creation, and spontaneous upending, of a million-gallon vat of custard, marrying Michael Saunders, the transformation of a pair of guided nuclear missiles into a sperm whale and a bowl of petunias, redesigning the interior of the Heart of Gold, turning Ford Prefect into a penguin, causing Arthur Dent to temporarily lose three of his limbs, transforming the desert world of Kakrafoon into an incredibly habitable oasis during a Disaster Area concert, ridding the people of Kakrafoon of their telepathy during the same concert and allowing for the discovery of Magrathea by Zaphod Beeblebrox. Other universal aberrations included:

- A team of seven three-foot-high market analysts came from the hole and died from a combination of asphyxiation and surprise.

- Arthur and Ford appeared to be at the sea front at Southend, Essex, UK, and were passed by a man with five heads and the elderberry bush full of kippers.

- A company “as crazy as a cup of waltzing mice” called Les Caves de Pyrene ruled the wine world.

–(with apologies to) The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, Douglas Adams

A friend of ours, whom one might call a restaurant entrepreneur, once wandered into Terroirs and looked around. Pointing vaguely at the bar, the busy décor and the effortless, lived-in look, he said “This is genius! Who designed it?”

No-one had. Terroirs had grown into its skin over the years. Our lack of money meant no conspicuous grand design or grand designer. Instead, we cut our cloth accordingly, and improvised. The evolving business story of Les Caves follows a similar arc. The less you have to work with, the more creative you can be.

Og Mandino said: “The prizes of life are at the end of each journey, not near the beginning; and it is not given to me to know how many steps are necessary in order to reach my goal. Failure I may still encounter at the thousandth step, yet success hides behind the next bend in the road. Never will I know how close it lies unless I turn the corner.”

That describes a glass that is half-full, which is the way we’ve always rolled. Some time, somehow, something would happen. Infinitely improbably, it did.

Andrew Jefford wrote an article in Decanter in 2017 detailing the unorthodox journey of Les Caves de Pyrène, how we ascended from the depths of rank amateurism (or the ranks of deep amateurism), operating by the skin of our teeth and the flexible friendliness of credit cards, eventually to become respected, known throughout the wine world, and even strangely institutional (yeah, yeah). I think he thought we were nefelibata, beatifically detached from reality.

Reasonable people adapt themselves to the world. Unreasonable people attempt to adapt the world to themselves. All progress, therefore, depends on unreasonable people. –George Bernard Shaw

Reason was never in our vocabulary. In fact, we were reasonably good at being unreasonable.

Les Caves has undergone numberless minor and major metamorphoses over the years. I like to think that we never followed a single trend in our lives (this much is true), but stuck rather to our beliefs and tried plenty of stuff. Mistakes? There were a few! We tried to do what we thought was right. And we still do. We became inextricably associated with the natural wine phenomenon, but that originated from a natural desire to drink hand-crafted wines made with the minimum of fuss or faff, not because it was trendy at the time to beat the drum for alternative wines. It certainly wasn’t. Eventually, it became a point of principle to seek out growers and wines that we liked rather than what the “market” (whatever that is) thought was fashionable. It’s fun to be explorers and push boundaries – we introduced the wines of South West France to the UK for goodness sake – and we still haven’t been forgiven for that! We were the first company to bring in the new wave of artisan Georgian qvevri wine producers. We quickly identified the excitement in Australia surrounding the young generation of experimental winemakers and populated our portfolio with their fun and funky offerings. We opened the Green Man and French Horn with an exclusively Loire natural wine list and shone a light on a region that was nearly entirely associated with Sancerre and Pouilly-Fumé. We became, via the auspices of our Italian brethren, the biggest distributor for artisan and organic wines in Italy. With such sales and marketing initiatives as sherry & tapas crawls, camping expeditions in the forest with wine growers (Aussie tree dwellers, need you ask), organising a never-ending roster of visits, tastings, pop-up wine events, instituting the Real Wine Promotion (which normally involves around 300 restaurants, bistros, bars, retailers and wholesalers through the UK and Ireland), we have demonstrated that – from the intimate to the grand scale – we are able to reach customers in new and dynamic ways.

I like to think that we never followed a single trend in our lives.

And yet, when you are amongst the first to stick your head above the parapet, you become automatically associated with a movement; if you articulate a credo, even a rough one, you open yourselves to the charge that you are being dogmatic. It is good to have a clear direction; for us it was highly logical to support small artisan growers, individualists who were less concerned about conforming to some outdated notion of appellation, preferring to express qualities of typicity, purity, drinkability and authenticity in their wines.

Having superb growers on your list does not maketh a superbly successful company. Living on your wits, and having to be imaginative and personable, is an excellent discipline for any growing business. Common sense, for instance, dictates that your greatest assets are the individuals who work for the company, so it is important to build a strong team and reward your employees with responsibility and shares (make it their company too, in effect). Following the golden rule of business by treating your suppliers and customers with respect, going the extra mile by making their business your business, is as strategically sensible as it is ethically sound. Furthermore, investments in spectacular events such as the Real Wine Fair (rather than spending money on pointless PR and bland generic tastings) have lasting value; they help to sow the seeds of a better/more informed/more enthusiastic wine culture and forge strong-and-long-lasting trade relationships.

A lot of people believe that in this age of materialistic individualism you will never be able to foster the spirit of collectivism. Many large wine companies seem to adhere to Mr Boffin’s credo – scrunch or be scrunched. There is certainly no room for sentiment in the big business world when you are competing in a finite market, operating on fine margins, and often effectively paying just to create turnover. The business becomes not about selling wine, but capturing market share. Many wine companies who chase growth at all costs aspire to be the one importer to rule them all, and thus reconfigure themselves to be all things to all people. Wine becomes an adjunct of business, a means to an end, and an almost inevitable dumbing down of the product, and the selling of the product, tends to take place. Meanwhile, small specialist wine merchants have identified a demand for authenticity and singularity. They are presenting the stronger sales arguments – quality and real value – they are forging the stronger relationships as a result.

For all the things that make Les Caves a strong company – a good sales team, excellent office back-up and a nifty wine portfolio – the extra ingredient is creativity, and the imagination to grasp the bigger picture. It is not just that we have gone into areas where many other companies would not dream of venturing, but that we’re always making strong connections by building on solid foundations. We don’t waste money on public relations gimmicks – our actions create the news stories (although we tend to fly under the news radar). We open restaurants and wine bars so that as many people can experience the wines in the medium for which they were intended. We co-ordinate one of the biggest artisan fairs so that consumers and trade may interact with growers. We set up sister-companies in other countries and ship around the world to build a wider community of like-minded wine-souls. Above all, we’ve kept our ‘satiable curiosity’ alive. As a company, we are not bound by convention, just because we seem to have arrived. As James Bryan Conant observed: “Behold the turtle. He makes progress only when he sticks his neck out.”

It is not just that we have gone into areas where many other companies would not dream of venturing, but that we’re always making strong connections by building on solid foundations.

Managing our time skillfully is key to be able to work on several fronts simultaneously. Today, Eric is off to Jura to wave his almsbasket at Pierre Overnoy, Manu Houillon, Philippe Bornard and sundry Ploussard-producing genii, then hopping over to Australia with Garth to meet with our Australian partners (Puncheon Bottles and Embla). Tending to Vino di Anna duties, he has also been virtually commuting back and forth between Etna and London the last three months. Eric’s a guy who flew out to Australia for a day just to sign a legal document. I’ve been in Budapest this past weekend presenting some of our new world wines at an artisan fair called Mitiszol?. Terroirs in Charing Cross, meanwhile, has been celebrating its 10th anniversary with a fortnight of growers’ pop-ups and takeovers. Beaujolais Nouveau day has just been and bubblegone, and we just wrapped up promotions of US wines by the glass to coincide with Thanksgiving. All the time, our pr bods are gathering in names of growers for the Real Wine Fair in 2019.

Since such multi-tasking is a virtual impossibility, it must have finite improbability. So, in order to know how feasible this is, all I have to do is to work out how exactly improbable it is, feed that figure into the finite improbability generator, give it a fresh cup of really hot tea…and turn it on!

And the Infinite Improbability Drive? Oh, that’s another story, called The Hitchhiker’s Guide to The Galaxy.

- Who is Les Caves de Pyrène?

- No, Hu is the leader of China

- No – it only works as a homophone

- Who are you calling a homophone?

- No, Hu is the leader of China

Yes, reader, we made it. There must have a day, a time, a moment at which we stopped biting our nails and realised that we had established a sustainable company. Once you have something to protect, then you concentrate on devising structures and disciplines to consolidate your gains and create a foundation for further growth. When you have nothing to lose, then you can be more fearless.

When Eric asked me to come on board the good coracle Les Caves (comprising four souls at that juncture) as a sales rep, I was a bit trepidatious. I had become accustomed to the closed environment of the restaurant wherein the sommelier has a captive audience, owns the knowledge, and can dictate the very nature of the wine experience. Selling wine in the outside world in those days was purely cold calling, jumping into the unknown. How quaint we were though. We actually used to write letters introducing our company and telling restaurateurs about our wines. The fax was another invaluable tool of the trade. I might even have kept a carrier pigeon in lieu of e-mail.

Hand sell: denoting an obscure or quirky wine that may only be sold by sommeliers to their customers by careful prompting (with a loaded gun) –The Real Alternative Wine Glossary

The real meat of selling was tramping the streets with an open bottle or two, screwing one’s courage to the sticking place to walk through that door and to be able to pitch your entire raisin d’être to a total stranger in a couple of pithy sentences.

I was directed back to the door on numerous occasions. Although, in virtually every restaurant I visited, I took a coffee for my pains.

There must have a day, a time, a moment at which we stopped biting our nails and realised that we had established a sustainable company.

“Good. Coffee is good for you. It’s the caffeine in it. Caffeine, we are here. Caffeine puts a man on her horse and a woman in his grave.”

And reduces an honest sales rep to a gibbering gibbon, Mr Hemingway.

One of the fine arts of selling is to have your own theme music or song reverberating in your mind as you tramp the streets. I could never go near Shaftesbury Avenue without…

I saw a werewolf with a Chinese menu in his hand

Walking through the streets of Soho in the rain

He was looking for the place called Lee Ho Fook’s

Gonna get a big dish of beef chow mein.

…bouncing in my head.

Cold calling is as good for the soul as it is as wearing for the soles of your shoes. You develop a moderately thick skin; humility becomes second nature. Indeed, humility triumphs over humiliation, because your major victory is to remain always polite and dignified in adversity. You smile…and leave.

When you do achieve a little success you feel like Alexander, that there is nothing impossible to him who will try.

I was directed back to the door on numerous occasions. Although, in virtually every restaurant I visited, I took a coffee for my pains.

Eric and I have never advocated standing over a potential customer and saying: “Go on, go on, go on…” as per an importunate Mrs Doyle, until their resistance evaporates. As the cliché goes, selling is as much about winning hearts and minds. A restaurant account where you have to batter down the door each time for each listing is not one where you have cultivated a relationship based on mutual trust.

Les Caves profile:

Philippe Lubac.

As Monsieur Lubac (how’s that for a nick-name?) can testify, it is dangerous to get drunk with Eric because you may find the King’s Shilling at the bottom of your wine glass. Our senior French buyer looks after some pretty groovy accounts in London, where he will often take “a quick bite of lunch”. For three hours. The Lubac (another name) has accumulated a formidable personal cellar (or Grand Cru cooking Burgundy as we call it) over the years, which is housed in a real cellar spiralling down to the earth’s core. Philippe’s knowledge of Rhône wines is encyclopaedic, he never wears the same tasteful designer t-shirt twice, his filing system is his back pocket, and once I described him as “so cool that cats could take correspondence courses from him”.

Coolness and effortless wine knowledge are invaluable assets when flogging wine. Philippe needs to don the armour of fiche to ward off any problematic questions hurled at him by the more nerdish sommelier-buyers. A fiche is a sheet containing technical information about a wine. Should you wish to spout chapter and verse about how tanky the tanks are, how many stems are employed in the fermentation, or what finings were used before bottling, the fiche is your improving bible. The art as a sales rep is to mug up on all the trivial stuff and bring it effortlessly to the fore, as if your knowledge of the wine was so personally extreme that you had actually measured the grams of free sulphur yourself.

Eric

Getting someone to try the wine is the main thing. We sometimes say that a wine is a more eloquent advocate for itself than any sales rep. It is what it is, after all. Good wine needs no bush and so forth. Although we were unknown as a wine company in the late 90s and early 00s, we were sufficiently confident that any wine in our portfolio, once tasted, would show that we were serious about what we were doing. Hence, we were, and still are to this day, liberal with our sampling. Whereas other companies might advertise, or hire huge venues for gargantuan tastings, we preferred the one-on-one approach, to share a glass of wine out of the bottle, and to tell its story.

This was not always possible and samples given “blind”, might well be purloined for personal enjoyment.

Eric once sent a sample bottle of one of our most expensive 1er cru Burgundies to a restaurant owner, a man, who shall we say, did not lack for self-esteem and would never fail to let you know that any conversation with him was a waste of his precious time.

After many unrequited phone calls, Eric finally went to the restaurant to follow up.

The follow up:

Eric: What did you think of the sample I left you?

Owner: I haven’t seen it, let alone tried it.

Eric: Well, what’s the wine like that you’re drinking at the moment – any good?

Owner: It’s excellent!

Eric: That’s the sample I left you!

Our pr budget at the time was our eating budget. One week, we ate out together six times. When you dine with Eric the wine list is not a document you look at to see what you would like to drink, it is rather the complete list of wines that you will order to taste (usually just a mouthful). Many’s the time we dined in restaurants when the sommelier had perforce to annexe other tables to accommodate the sheer number of bottles that we had ordered – and almost instantly discarded after a prefatory sip.

When you dine with Eric the wine list is not a document you look at to see what you would like to drink, it is rather the complete list of wines that you will order to taste (usually just a mouthful).

I’ve learned a lot from Eric. His palate is phenomenal; he can usually see straight into the heart of the wine. Or know instinctively whether it possesses a heart or not. Once we ordered a bottle of Californian Pinot Noir. It can happen. The wine was attractively ruby-hued and smelled so inviting. I said to Eric:

“Its (Pinot’s) flavours, they’re just the most haunting and brilliant and thrilling and subtle and…ancient on the planet.”

Maybe not those exact words.

Eric sniffed sniffily. “I give it five minutes”.

Five minutes? To open up still further? The aromas were already hedonistic, the fruit was cornucopiac, even pornucopiac.

He took a swig of the friand, tasted fruit and freshness, a flavour that turned briefly and looked back over its shoulder at the summer before last, but didn’t pause even to shade its eyes. (The Vintner’s Luck, Elizabeth Knox)

After a couple of further swigs of this particular friand, I was puzzled. The sweetness was now palling, the oak lacquer was apparent, cloying and almost charcoal-y. On the five-minute buzzer, I frowned. The wine had imploded. It was almost a happy-slapping wine: one of those oak monsters that whack you across the face before even touching your lips. But so cunningly disguised behind the veneer of luxuriance!

At that moment I understood that winemaker intervention may unmake the wine by means of the imposition of extraneous flavour and oenological trope. The fruit may have been beautiful, haunting, thrilling and brilliant, but the maquillage was less so. The result?

Therefore, to be possess’d with double pomp,

To guard a title that was rich before,

To gild refined gold, to paint the lily,

To throw a perfume on the violet,

To smooth the ice, or add another hue

Unto the rainbow, or with taper-light

To seek the beauteous eye of heaven to garnish,

Is wasteful and ridiculous excess.

–King John, Shakespeare

Eric looked at me and nodded.

The other lesson is in generosity of spirit. Follow your instincts and feelings – it’s as relevant to understanding wine as it is people. Wine is for sharing and for enjoyment.

You are what you taste (2010)

- The best bottle is the empty bottle – drunk by people who enjoy the taste of wine.

- The worst bottle is the empty bottle – emptied down the sink.

I have this anthropomorphising theory that wine responds to the person tasting it. The more open-minded and open-hearted the person you are tasting with, the more generous the wines seem to be. And the converse also true – negative attitudes or preconceived opinions beget bad tasting experiences.

In the wine trade we seem to be in thrall to notions of correctness. We even say things like: “That is a perfectly correct Sauvignon”. Criticism like this becomes an end in itself; we are not responding to the wine per se, but to a platonic notion of correctness. This is the zero-defect culture which ignores the “deliciousness” of the wine. We cannot see the whole for deconstructing the minutiae, and we lose respect for the wine. We never mention enjoyment, so we neglect enjoyment. This reminds me of the American fad for highbrow literary criticism, imbued with a sense of its own importance. Wine is as a poem written for the pleasure of others, not a textual conundrum to be unpicked in a corridor of mirrors in the halls of academia. If the path be beautiful, let us not ask where it leads.

When the cultured snob emits an uncultured wow, when the straitjacketed scientist smiles, when scoring points becomes pointless…

And why should wine be consistent? There are too many confected wines that unveil everything and yet reveal nothing. The requirement for homogeneity reduces wine to an alcoholic version of Coca-Cola. Restaurants, for example, are perhaps too hung up on what they think customers think. Patrick Matthews in his book The Wild Bunch quotes Telmo Rodriguez, a top grower in Rioja Alavesa. “We were the first to try to produce the expression of terroir, but people didn’t like the way it changed the wine. The consumer always wants to have the same wine; the trouble is if you have a bad consumer, you’ll have a bad wine.” And, of course, if you push wines that are bland and commercial, then the public will continue to drink bland and commercial wines.

When the cultured snob emits an uncultured wow, when the straitjacketed scientist smiles, when scoring points becomes pointless, when quite athwart goes all decorum, when one desires to nurture every drop and explore every nuance of a great wine, surrendering oneself emotionally to the moment whilst at the same time actively transforming the kaleidoscopic sensory impressions into an evocative language that will later trigger warm memories, it is that the wine lavishes and ravishes the senses to an uncritical froth. Greatness in wine, like genius, is fugitive, unquantifiable, yet demands utter engagement. How often does wine elicit this reaction? Perhaps the question instead should be: How often are we in the mood to truly appreciate wine? Rarely, must be the answer, for if our senses are dulled or our mood is indifferent, we are unreceptive, and then all that remains is the ability to dissect.

Ah yes, the furrowing of the brows denoting concentration, the sepulchral hush, the lips curled in contumely, the business of being serious about wine – the calculated response based on a blend of native prejudice and scientific scepticism. But all wines are different and there is a story behind each one. Good humour, good company, good food and open-mindedness are the best recipe for imaginative appreciation. Leaving aside that dross is dross for a’ that, the mindset of the critic is often to anatomize for the sake to it. I regularly find that tastings degenerate into a frenzy of “banalysis-paralysis”. Too oaky, commented one sommelier about one particular Chardonnay that we were tasting. Too acidic, rejoined another. Too shoes and ships and sealing wax, interjected a third. Too cabbages and kings, prescribed the first. Criticism like this becomes an end in itself, a stylized response uncoupling pleasure from the experience, as if registering subjective pleasure should be invalid.

How often are we in the mood to truly appreciate wine? Rarely, must be the answer, for if our senses are dulled or our mood is indifferent, we are unreceptive, and then all that remains is the ability to dissect.

For me the pleasure of wine is pleasure: occasionally we should resist analysing our experience in the same way as when we read a poem or listen to music we do not always have to clinically dissect its beauty and rearrange it into dull prose. Too often we strain for definitive answers; we want to consciously validate our experiences rather than to feel them on the pulses.

Tasting or experiencing wine involves a portion of humility, of giving of oneself as well as taking. When we smell a wine and turn it over in our mouth, we become engaged in the process of converting fermented grape juice into language. Our sense of smell is inextricably linked to our memories; in fact, smell unlocks memories and language shapes them into a tangible reality. Our highly personal response to a wine is what exalts our imaginations. This is not a new idea. Wine has been seen as the inspiration to unlock creative power of poetry and music since the ancient Greeks. Now we are all critics to the nth degree. If your tasting compass is set to due WSET (sic) you can totally miss the aesthetic and sensual journey the wine is taking you on. Which would be a crying shame.

He who can distinguish a good fruit from a bad with his palate does not have to be able to express the distinction through a chemical formula and does not need the formula to recognise the distinction. –The Theory of Harmony, Arnold Schoenberg

Quite.

In 2018 I was invited to be a member of a panel at the London Wine Trade Fair to talk about the innovative approaches we had adopted in our respective businesses, in order to cope with the various pressures such as rising costs, small vintages, an increasingly competitive market.

As the other members of the panel detailed their operational strategies, I felt somewhat like Sir Geoffrey Boycott preaching the virtues of line and length (and not swishing in the corridor of uncertainty with his grandmother’s stick of rhubarb). Or, in other words, keep it simple and eschew gimmicks.

There is a reverential obsession for “the market”, as if it is a monolithic energy source that one can plug one’s business model into and animate into success. Wine is wine, taste is taste, and individuals are individuals; by focusing so intently on business methodology you begin to lose touch with the products you are buying and selling (which are real) and the people with whom you are dealing (who are real).

Les Caves profile:

Gideon Clow

Inveigled to join Les Caves many moons ago when he was the buyer for Villandry restaurant, rugby-dad Gid manages only behemoth accounts – with the odd gargantuan one. All the world’s his spreadsheet; he loves marshalling his armies of statistics and finding a stray ¼ of one % to save. He buttonholes our buyers with requests for wines that we’ve never heard of (decent Prosecco rosé, decent Pinot Grigio rosé…). No blush Zin so far…He is now Key Keg king. Take that, Steve McQueen! A danger to the Atlantic pulpo population, he’s racked up more trips to Galicia than the rest of the company put together.

Slightly Creative, Mostly Boring – A Sustainable Business Approach (2018)

What is the Chinese market doing? What will be the next big grape variety? How can we transport wine to reduce costs? How can we influence consumers? What can we learn from the craft brewing experience?

“By nature, men love newfangledness.” –Chaucer

You will hear a lot of hubbub in the wine trade about the constant need for business innovations and solutions. The problem with this is that there are factors that are inevitably determined outside our control, ranging from the turbulence of the weather and the way it affects grape vintages and consequently prices, to socio-political factors and sheer random events. To apply any innovative methodology into a potentially chaotic system is “to see what flies”, rather than to know what outcomes will eventuate. In the end, managing a wine business usually boils down to solid virtues rather than meretricious gimmicks.

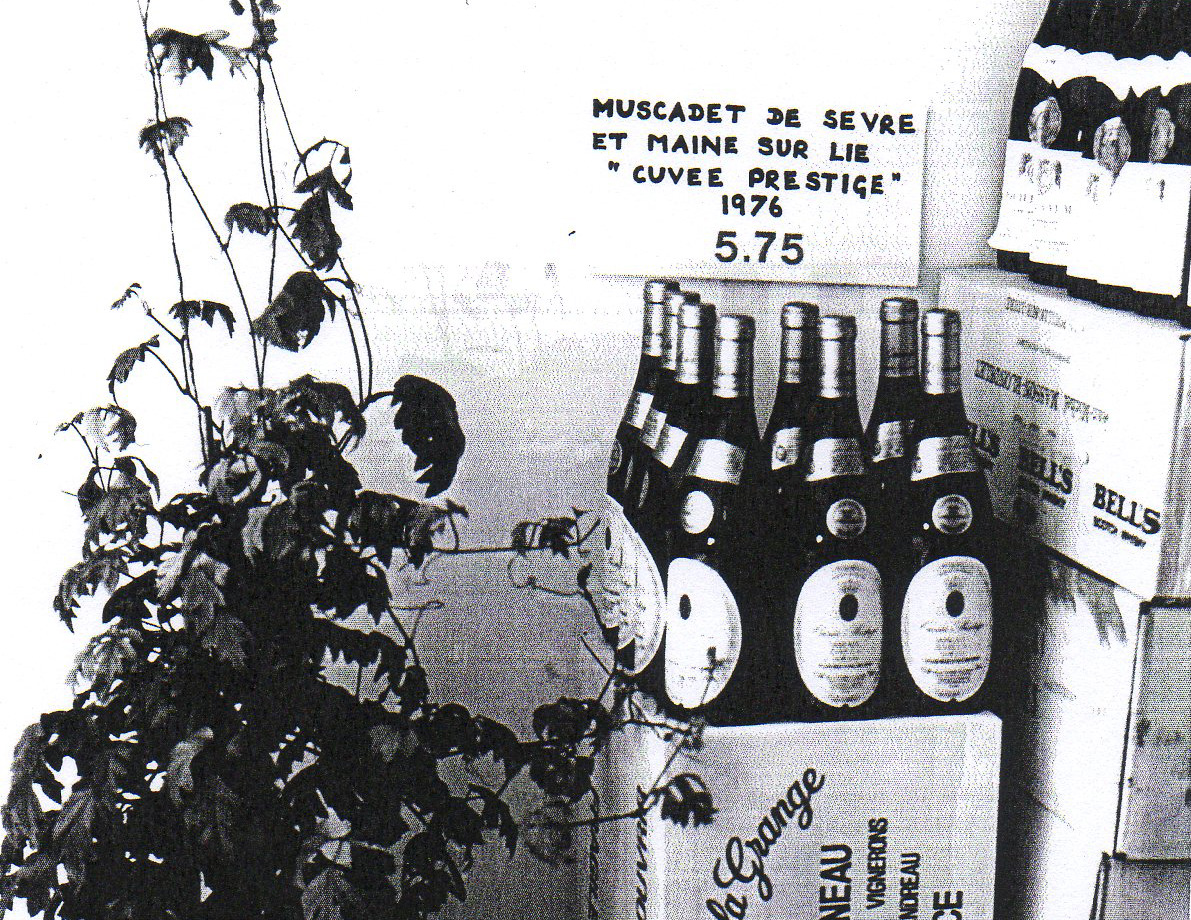

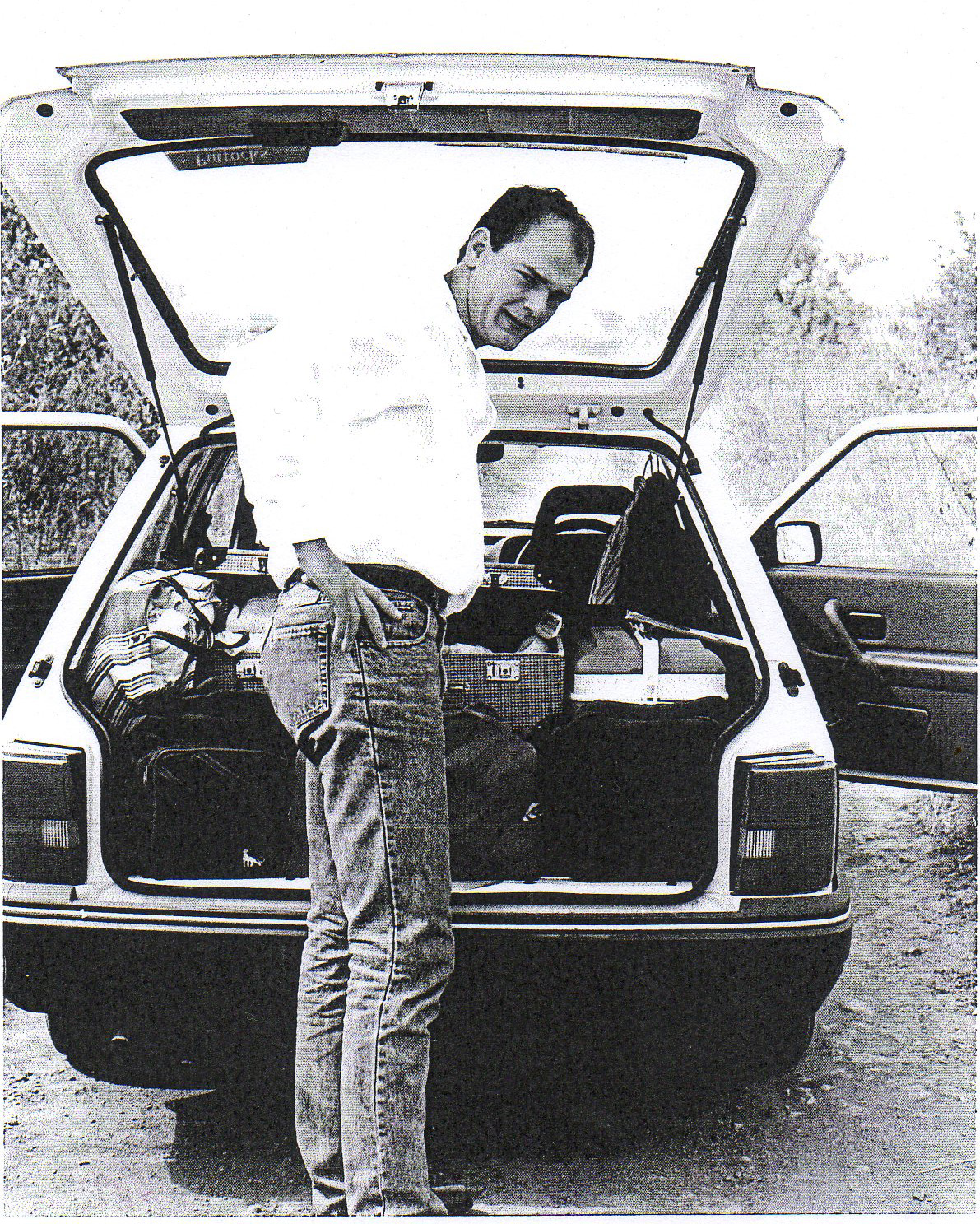

Over the years, Les Caves de Pyrène has grown from an embryonic hobby-business, selling a handful of obscure French country wines out of the back of a battered van, into a middle-sized company importing from twenty countries; one that has sister operations in Italy, Spain and Australia; is a major partner in a group of wine bars, and finances one of the biggest artisan growers’ wine fairs in the world. During that transformation we’ve improvised, taken risks, ridden the financial rollercoaster of three recessions, but also stuck to our core principles.

Firstly, we have eschewed taking on external investment to expand turnover. Our model, such as it is, is to grow organically, be that exponential or snail’s-pace growth. The biggest investments we have made ourselves have been launching the Natural Wine Bars company (Terroirs, Brawn, Soif etc) and bankrolling The Real Wine Fair. Opening the various wine bars has been instrumental in allowing natural wines to be showcased in a (user)friendly environment, whereas the rationale behind the Real Wine Fair was not only to celebrate natural wines, but also to broaden their appeal by bringing the growers to meet the trade and the public alike. There was no immediate tangible financial benefit as a result of either of these investments, but, just as a farmer may use organic or biodynamic preparations before planting his or her vines to ensure a healthy environment for them to grow in, so it was part of seeding interest and establishing the preconditions whereby a more dynamic, informed and open-minded wine culture might eventually flourish.

Our wine business itself operates simply. We reward loyalty and talent by offering shares, so that employees feel that they are valued and working for themselves. The greatest asset any company has are the individuals that work for it. We endeavour to observe the golden rule of business and treat both suppliers and clients with due respect. It is not just a karmic thing (although it is!), it is also best business practice. Finally, we think of the wines we buy not as commodities, brands or products, but as real things crafted by individuals and hence, what we are selling has real value. These solid business foundations, in our opinion, have helped to insulate the company somewhat against the volatility of a market economy.

Having grown steadily for 20 + years, we believe that is important to digest that growth and become as lean and well-run a business as possible.

Recently, however, as with many wine companies in all sectors of the trade, we have encountered profound economic challenges. For starters, a succession of small vintages has impacted severely on the cost of grapes. Meanwhile, a weak trading currency, allied to increased shipping and transport costs and the growth of foreign markets, has compounded the upward pressure on wine prices. Business is being squeezed throughout the UK as on-trade establishments, which constitute the majority of our business, are suffering from massively-increased costs imposed by an inflation-busting cocktail of rent and rate rises, and higher wage costs. It has been described as the perfect storm – and it is. On the one hand, we have to respect that our growers need to be paid more to survive the aforementioned problematic vintages (even solutions such as spreading price increases are only deferring the pain) and that restaurants, bars and small retailers may have to consider increasing their margins in order to compensate for their higher costs.

Adjustments are required therefore. The bigger the company, the more difficult it is to make the rapid changes necessary to meet these challenges. (The analogy of the supertanker taking a long time to turn around is apt here.) Nor is throwing money around to find a solution the appropriate means of strengthening your business. Small enterprises, conversely, can be nimbler and more reactive, as they don’t need to do lengthy audits or exhaustive restructuring in order to save money, whilst implementing strategies is that much easier.

In straitened times, cashflow is vital for any company, big or small. Having grown steadily for 20 + years, we believe that is important to digest that growth and become as lean and well-run a business as possible. There are various measures one may take to realise this intention. One may, for instance, examine one’s wine portfolio critically, reducing it where necessary (especially in areas where there is duplication) and ensuring that every wine works to maximum effect. Ensuring that stock turns over in a reasonable period depends on disciplined ordering and refining the just-in-time logistics. At the other end of the process, preserving profit margins is crucial. Every single % counts. The wine trade is rife with companies throwing out loss leaders, dumping stock and participating in Dutch auctions – this drive to the bottom leaves those companies with little or no room for manoeuvre. Turnover, per se, does not, after all, equal profit.

The quality of business hinges not on headline-grabbing actions, but on developing sustained narrative of strong relationships, with excellent communication, on the everyday servicing of customer accounts, as well as maintaining quality of product and ensuring that you foster the deserved perception that you are providing value for money.

Over the past few years we have started to work with co-ops and medium-sized producers to create labels – at a competitive price – in the style that we specialise in (organic, unfiltered, more naturally made wines). In this respect we have taken a leaf out of the book of larger companies who practise this as a matter of course. For us, however, quality is paramount.

We have looked at different packaging formats such as key kegs, not solely as a cheaper alternative to bottled wine, but for the various other advantages they might bring. And we work strenuously on the sales service. We encourage (and educate) customers to change their lists more often, and to explore different grapes, styles and wine regions. We work with these customers to create a wine culture in their establishments by sponsoring or devising training programmes. When prices are increasing you have to add value to the wine experience and elevate wine from being the mere commodity of booze into something rather more exciting and involving.

As strong and stable (maybe I shouldn’t use that expression!) as your business may be, you should also align yourself to other strong businesses. In times of financial uncertainty, rather than chasing turnover, you should audit whom you are dealing with. Recently, a number of big chains have pulled the plug on some, or all, of their operations. The companies that have been supplying these chains with wines offered at massive discounts, have lost doubly as a result. Wine companies have it in their power to discourage the perception that wine is an inexhaustibly cheap commodity to be used by restaurants to generate unfeasibly high gross profit margins. Of course, we’re in a competitive industry, but nobody wins when businesses go bust.

In summary, there is no single magic bullet that one can fire to transform the fortunes of a business (managing a business is about constant evolution rather than dizzy-headed revolution). There are, however, numerous small measures and gentle refinements that one can make. For an enterprise to be truly sustainable it needs to be founded on sound practice, otherwise it will be forever battered by the cyclical nature of the market (as Shakespeare wrote: “The whirligig of time brings in his revenges”). Chasing trends in the wine world is like chasing rainbows; real success is proven on a long-term strategy, which, boring as it may sound involves protecting what you have, banking steady profit, and keeping both your suppliers and customers happy.

Les Caves profile:

Elena Polouian

With the Mission Impossible theme tune belting out in the background, our Elena P skilfully pilots the supertanker that is the CdP’s shipping department. She is the multi-tasking polyglot’s polyglot conversing at a million miles an hour with our growers across the planet. She’s thoroughly familiarised herself with the arcane procedures, types of containers, refrigeration and if you want to know the weather conditions in some far-flung part of the wine globe, you don’t need to ask the meteorological office. Elena, and her merry band of shipping folk, ensure that we receive wines just-in-time from the farthest shores of manana-shire (except Crete).

Digression Concerning the Wine Trade and The Golden Rule of Business (2016)

Forgetfulness. A gift of God bestowed upon debtors in compensation for their destitution of conscience. –Ambrose Bierce

It’s not just dog eat dog. It’s dog doesn’t return other dog’s phone calls –Woody Allen

Morals? Can’t afford them guv’nor. –Alfred Doolittle, Pygmalion, George Bernard Shaw

Those are my principles and if you don’t like them I have others –Marx, Groucho

I was musing the other day how there is often a disjunction between the way we conduct ourselves in our private and social lives and the way we do business. Business, big business, often seems to exist in neo-Darwinian bubble, where sentiment is absent and exploitation is rife. Bad practice is not only accepted, it is actively encouraged. What is also striking is that when certain people behave with an iota of propriety, they are lauded to the skies for it. Multi-national corporations and supermarkets receive awards for green initiatives or ethical behaviour. Credit where it is due, although ethical behaviour should be the sine qua non of every business. One should highlight the many unsavoury aspects of big business behaviour: from encouraging over-consumption (and thus exploitation of the planet’s dwindling resources) to pushing suppliers to the limit by screwing down the prices year after year, forcing the same suppliers to accept late payment and making them jump through hoops of red tape.

A cautionary tale of a Hollywood-star-owned vanity-project restaurant that boomed in the 1980s. Back in the day they were one of our biggest accounts, the debt they racked up was sizeable, potentially life-threatening for Les Caves. The restaurant, if we can call it that, closed its doors, ostensibly to do a refurb, shuffled the personnel and structure of the company and performed one of those magical Phoenix company resurrections. As with so many maladministered companies it was difficult to discern whether the endless payment prevarications were the result of sheer incompetence, or whether the principals were congenitally devious. Over the months our credit-control chased with phone calls, followed by letters, then reminder letters, then final demands, then solicitor letters and threats of court summons.

When we discovered that Planet Hollywood was about to have a relaunch party and had invited the usual crew of z-list celebrities, freeloaders and public relations groupies, we were more than a mite peeved. Eric phoned one last time, and explained to the accountant that he would appear in the middle of the party to remove the tables and chairs from the restaurant. If necessary, from under the backsides of said z-list celebs. He conjured up the image of social embarrassment on an epic scale, a kind of enforced celebrity chairs – without the chairs. Reader, the money was transferred into our bank account within the hour.

Owing money brings out the worst in human and corporate nature.

In the late 80s, throughout the 90s and even later on, far too many restaurants would be opened by dilettantes and trustafarians on the basis of their hefty social address books. Conforming to the stereotype of “the trust fund baby” they would hire consultants, then more consultants, change their minds three times in one morning, invite le tout demi-monde of pr folk and fellow trustafarian-restaurateurs to a succession of lavish opening parties (which would be subsidised entirely by their food and drink suppliers), use the restaurant on account to entertain their friends, and then eventually get bored with the grunt work involved in running a successful business.

One of our customers was straight out of PG Wodehouse’s central casting for Eggs, Beans and Crumpets. Although amiable, he was not a particularly good egg. He was forever unobtainable when matters of paying debt arose, normally using that as clarion call to go on holiday to an expensive ski resort or Caribbean island, depending on the time of year.

Eric, tired of being fobbed off by the usual prevarications, decided to beard the beardless debt-avoider in his office. He went up the stairs and entered the outer room. A bored looking young woman, was filing her nails.

Eric: I’m here to see Cholmondeley Plomondeley. (pronounced Chumly-Plumly and not his real name).

PA: I’m afraid you can’t see Chumly-Plumly. He is not in the office today. I am not even sure where he is.

Eric replied: I can see him through the glass door. He is sitting behind his desk in his office.

Evidently, Chumly-Plumly had borrowed Harry Potter’s Cloak of Invisibility and slipped into inner sanctum unbeknownst to his somnolent PA.

There’s a saying in the Old West (America, not Fulham): “Don’t piss on my back and tell me it’s raining.”

Dostoevsky said that the man who lies to himself and listens to his own lie comes to such a pass that he cannot distinguish the truth within him. The little lies in business become so deep-rooted that corruption is complete – lie after lie is spun to protect the original lie. It’s so unnecessary. Lying about the status of a business becomes an addiction. Think Pangloss’ “all is for the best in all possible worlds” combined with “the cheque is in the post”. We’ve been given excuses such as “he is on his private yacht and we can’t disturb him” to “his pen ran out of ink.” This is in “the dog ate my homework” category of lie. Deferral of payment and bad debt create a nasty ripple effect, wherein wine merchants are unable to pay their suppliers on their time. The business world depends on people not breaking the chain.

We’ve been given excuses such as “he is on his private yacht and we can’t disturb him” to “his pen ran out of ink.”

A wine company does not exist to judge its customers’ business strategy, but is honour-bound to audit how they run their business.

Without wanting to sound pompous, I think we can say that we strongly subscribe to the Golden Rule, which underpins the teachings of every single major religion on earth.

- The Golden Rule or ethic of reciprocity is a maxim, ethical code, or morality that essentially states either of the following:

- One should treat others as one would like others to treat oneself

- One should not treat others in ways that one would not like to be treated (also called the Silver Rule)

- The Golden Rule is arguably the most essential basis for the modern concept of human rights, in which each individual has a right to just treatment, and a reciprocal responsibility to ensure justice for others. A key element of the Golden Rule is that a person attempting to live by this rule treats all people with consideration, not just members of his or her peer group. The Golden Rule has its roots in a wide range of world cultures, and is a standard that different cultures use to resolve conflicts.

“Zi Gong asked, saying, “Is there one word which may serve as a rule of practice for all one’s life?” The Master said, “Is not RECIPROCITY such a word?” —Confucius, Analects XV.24

Alternate “Golden Rule”

An alternative, more realpolitik definition of the “Golden Rule” cited in business and politics, with a distinct twist on the expected religious/moral definition, is “He who has the gold, makes the rules.” Citation of the Rule under this meaning is often meant to make a naive, weaker party aware of the dynamics of an interaction in which one party has greater resources and therefore greater power than another. The Alternate Golden Rule tends espoused by bigger companies who threaten to withhold business (or payment) unless you play according to their rules. Often, he that pretends to have the gold, doesn’t really have any gold at all, rather he has a long line of credit and a wealth of entitlement and chutzpah.

Why shouldn’t businesses adhere to the Golden Rule? We hear of good business practice, but is it possible, in the real dawg-eat-dawg world, to run a holistically-sound-yet-economically-effective business at the same time? I am inclined to think so. What holds people back is their distrust of others, the feeling that they are going to be stabbed in the back, or in the front, the cultivation of self-preservation and the pursuit of profit at the expense of ethical generosity. Most businesses are structurally set up to chip away at costs in order to improve profit margins, rather than dedicating themselves to providing excellent service. To run a lean operation is an admirable objective, but when the cuts go through the bone into the very marrow of the operation, the ethical foundation of the business begins to crumble. Without moral imperatives, partnerships may be sacrificed, whilst quality and passion – considered a sentimental distraction – are jettisoned. Bad business practice fosters ill will, the loss of staff (who are the most valuable asset of any business) and the diminution of the product(s) that the business is selling.

The Golden Rule can surely exist within the capitalist model, because it is to everyone’s financial advantage that we follow best practice and create a sustainable (by which I mean an ethical) economy.

One final story. We worked very well with a group of bistro-style restaurants who were on an expansionist course. One day we found out that they have bought into a chain of bars; the next thing we knew they had gone bust, owing us a huge amount of money. The sites were purchased by a group which had a small chain of café bars.

Eric drove up from Guildford in the van to retrieve some wine, any wine, from the site. Anything to set against the cost of our swingeing losses. When he entered the building, the owner came down to confront him.

Ghostly Ennio Morricone is playing in the background

Eric: I’m here to take back our stock.

Owner: It’s not your stock, it’s our stock – it came as part of the deal. And now it’s ours by right.

Eric: It’s not your stock. It has not been paid for.

Owner: Yes, it’s mine.

Eric: No, it isn’t. That is stolen stock and I’m going to steal it back.

Owner: You can’t do that. I’m going to call the police.

Eric: Go ahead. I will just tell them it’s stolen.

Impasse.

Blondie: If you shoot me, you won’t see a cent of that money.

Angel Eyes: [frowning] Why?

Blondie: I’ll tell you why.

[Blondie kicks the coffin lid open]

Blondie: Cause there’s nothin’ in here!

Owner: Ok, ok, I see your point, but can you leave us some? We’re just about to open and we need some wine.

Silence

Tell you what, you can have one listing on our list when we open.

Eric: And you can have stock for one day at a time. And I will deliver it every day personally, if need be.

So, it was agreed. We had our listing. And over time, mutual distrust grew (through plain-talking) into mutual respect, and eventually into admiration, friendship, and, in the end, a kind of partnership. The account in question became our biggest account for several years, the chairman became a shareholder in Les Caves, and the financial director, became our financial director.

Positive Reinforcement

“Each time you live up to the Golden Rule, your reputation is enhanced; each time you fail, it is diminished,” writes author and speaker Fred Reichheld in an article in Harvard Business Review.

As it turns out, rising above the situation and treating others decently is just as important in the business world as it is in our personal lives. A cut-throat business strategy may work at first, but as Robert Axelrod observes, over time it will, ironically, “destroy the very environment it needs for its own success.”

Building your business sustainably involves not stepping on others to climb the corporate ladder, treating your team, your customers, your vendors, and competitors fairly.

As it turns out, rising above the situation and treating others decently is just as important in the business world as it is in our personal lives.

As wine importers (dealing with artisan growers) and as suppliers (dealing with restaurants, retailers and wholesalers) it is commercially sensible and ethically important for us to understand the business and livelihoods of the people that we are dealing with.

Henry Ford recognized the value of this simple concept. “If there is any one secret of success,” Ford is quoted as saying, “it lies in the ability to get the other person’s point of view and see things from that person’s angle as well as from your own.”

We bleed empathy for restaurants. I worked in them for years, as did Philippe. Phil Barnett owned his own gaff, Didier came to us from Club Gascon, and Eric and Liz had a small French bistro in Guildford called The Gate. We know what works, and we definitely know what doesn’t work.

When Liz was managing The Gate, she put together one of the best small wine lists I’ve ever seen. It broadly took the form of questions appealing to different sensory/sensual/emotional requirements, such as “Do You Feel Like A Long Luxurious Soak in a Bubble Bath?” or “Do You Scan The Small Ads in Search of Exotic Far-Off Holiday Destinations?” Ah, the days of small ads and bubble baths. For our younger listeners I have one word for you: Badedas!

Les Caves profile:

Liz Reid

As one of its founding spirits, Liz’s memories of Les Caves date back to prehistoric Santat-times when Les Cavistes were indeed caves dwellers, wine lists were Gascon-heavy and verbiage-light, and Eric had a thatch of hair. In those days of yore, Liz was jack (jill?) of all trades, performing umpteen vital tasks – at the same time. Now she beavers tirelessly at being Liz-the-technogeek, cross-examining our growers on the whys, wherefores and SO2 levels of their wines and not accepting “non”, nor Gallic shrugs for an answer.

Price rises result in the wine trade having an existential crisis. These are not in the control of wine merchants, but are influenced by two respective volatile climates – namely the weather and the economy. Upward pressures include, inter alia, the size and quality of vintages, the cost of raw materials, increasing transport costs, increasing wage costs and the (mis)fortunes of the pound against other currencies. When it comes to duty increases wine is very heavily penalised. Most suppliers will absorb the greater part of a price increase as they wish to remain competitive and not inconvenience their customers. You might think that those who purchase wine would appreciate its real value and also the market pressures that drive prices up (mainly) and down (very occasionally). Adhering to their side of The Golden Rule would involve customers understanding these economic rhythms and maintaining a loyal and productive relationship with their suppliers. This is not invariably the case, however, as business is inevitably auctioned off for money, while suppliers seek to undercut each other in order to grab a diminishing piece of the financial pie. All of which sets a very bad precedent, for it creates adversarial relationships based on zero-trust, leads to corners being cut, and goes on to affect the whole supply chain.

Challenging necessary price rises may be topical, but endemic behaviours include avoiding payment, not communicating intentions, not appreciating quality and not rewarding exceptional service. We all understand about cash flow and margins; observing The Golden Rule involves refining and even disciplining your business strategy, ensuring that you don’t bite off more than you can digest, whilst respecting the terms and conditions of a contract. If an arch-capitalist like Henry Ford can see the benefits of treating people in the business supply chain with respect, then others may wish to re-evaluate their business practice. In the final analysis, business is about people and not about numbers and spreadsheets. The most successful restaurants – in our experience – are run by people who care deeply about what they are doing. The businesses that go to the wall may have been started with the best of intentions, but eventually lose their way because the people that run them spend all their energy on making deals and cutting corners rather than focusing on what makes an enterprise really successful.

To be continued in Part Two…