A topographical, historico-cultural, vinological account of a swift trip to Slovenia, a small but vital country situated in southern Central Europe located at the crossroads of main European cultural and trade routes, bordered by Italy to the west, Austria to the north, Hungary to the northeast, Croatia to the south and southeast, and the Adriatic Sea to the southwest.

Four major European geographic regions meet in Slovenia: the Alps, the Dinarides, the Pannonian Plain, and the Mediterranean. The Alps—including the Julian Alps, the Kamnik-Savinja Alps and the Karavanke chain, as well as the Pohorje massif—dominate Northern Slovenia along its long border with Austria. Slovenia’s Adriatic coastline stretches approximately 47 km from Italy to Croatia.

The Collio border. Josko Gravner has a vineyard on the Slovenian side.

The term “Karst topography” refers to that of southwestern Slovenia’s Karst Plateau, a limestone region of underground rivers, gorges, and caves, between Ljubljana and the Mediterranean. On the Pannonian plain to the East and Northeast, toward the Croatian and Hungarian borders, the landscape is essentially flat. However, the majority of Slovenian terrain is hilly or mountainous.

Historically, the current territory of Slovenia was part of many different state formations, including the Roman Empire and the Holy Roman Empire, followed by the Habsburg Monarchy. In October 1918, the Slovenes exercised self-determination for the first time by co-founding the internationally unrecognized State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs. The Slovenians mostly wanted to be with Germany and Austria, but merged that December with the Kingdom of Serbia into the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (renamed Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1929). During World War II, Slovenia was occupied and annexed by Germany, Italy, and Hungary, with a tiny area transferred to the Independent State of Croatia. Afterward, it was a founding member of the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia, later renamed the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, a communist state which was the only country in the Eastern Bloc never a part of the Warsaw Pact. In June 1991, after the introduction of multi-party representative democracy, Slovenia split from Yugoslavia and became an independent country

According to historical record, the beginnings of viticulture and winemaking in the area of modern-day Slovenia can be traced all back to ancient Noricum, the predecessor of Carinthia. Evidence of this is inscribed in the stones laid in Roman times featuring the vine, the wine vessel and two panthers (2nd century) above the main entrance to the Cathedral of Holy Lady (Gospa Sveta). The Celts in all likelihood grew vines and produced their own wines. When the Romans advanced into the area of modern-day Slovenia, viticulture methods changed, and vines and wine production methods were introduced. “Vinum Pucinum”, which grew on the rocky hills (»pe?ine« in Slovenian) east of Aquileia, was mentioned in the Roman annals. The situla (an ornamental Early Iron Age drinking vessel) from the village of Va?e (5th century BC) denotes an ancient (and social) wine culture.

The famous situla of Va?e

By the Middle Ages, the Christian Church controlled most of the region’s wine production through the monasteries. Later on, a new organisation was established to oversee viticulture on the Slovenian territory, one which survived until 1848. The so-called gorska pravda comprised an assembly of vini?ars the workers, who cultivated the vineyards, and their masters – the owners of the vineyards.

Under the rule of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, privately owned wineries had some presence in the region but steady declined following the empire’s fall and the beginning of Yugoslavia. By the end of the Second World War, co-operatives controlled nearly all of the region’s wine production and quality was very low as the emphasis was on the bulk wine production. The exception was the few small private wineries in the Drava Valley region that were able to continue operating.

The long and rich history of viticulture resulted in a wide collection of local Slovenian vines, mostly white ones. In his Austrian verse chronicle, Ottokar names some varieties of Slovenian wines namely Teran (terran), Vipavec (win von Wippach), Rebula (reinwal), Pinela (pinol), wine from Milje (muglaere) and wine from Brda (ecke).

In Slovenia, many vineyards are located along slopes or hillsides in terraced rows. Historically vines were trained in a pergola style that optimizes fruit yields. However, the emphasis on higher quality wine production has encouraged more vineyards to switch to a Guyot style of vine training. The steep terrain of most vineyards encourages the using of manual harvesting over mechanical.

There are four main regions – Vipava Valley; the border area of Collio (Goriska Brda); the Karso/Istria bit near Trieste and finally the Slovenian part of Styria near the town of Maribor. Climate is warm and Med in the SW, cooler, wetter and more continental in the NE. Interestingly, Gravner has his best vines in Slovenia; I could see his Ribolla vineyard from my room and equally many Slovenian producers have vines in Italian Collio!

Farming in Slovenia is mostly conventional – all the growers I met, however, were organic with one hardcore. The main grapes planted in the Collio region are Rebula (from which the highest quality wines are made), Tocai/Jakot, Malvazija, Sauvignon and Cabernet and Merlot. In Styria, it is Renski Riesling, Laski Riesling (Welschriesling), Sauvignon, Chardonnay and Pinot Noir.

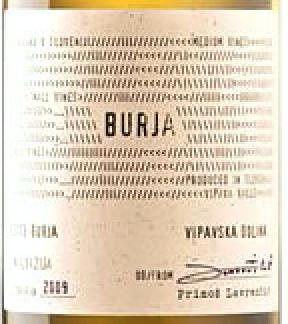

Photo credit: Burja Estate

Burja – Primoz Lavrencic

First stop was Posestvo Burja in the Vipavska Dolina. Rich descriptions of Vipava viticulture and winemaking can also be found in winemaking for Slovenes (Vinoreja za Slovence – the first Slovenian book on viticulture) written by Matija Vertovec in 1844 and in The Glory of the Duchy of Carniola (1689) by Johann Weikhard von Valvasor.

According to location and natural geographic features, the Vipava Valley is very much betwixt and between, wedged between the Trnovo Plateau to the north, and Karst to the south, a mixture of Alpine, Mediterranean and Continental climates. The Vipava Valley is also the windiest part of Slovenia, noted for the gusts of its famous wind which blows with furious gusts – the bora (burja)

I met Primoz Lavrencic from Burja – he is a young, progressive guy. His wines are distributed by our colleagues, Les Caves Italia, and he is married to Benjamin Zidarich’s sister, so plenty of things in common. The Lavren?i? family moved in the Vipava Valley as far back as 1499, and like the majority of the population, engaged in agriculture and viticulture. Primoz’s mother’s family were blacksmiths, and also owned some vineyards.

Respecting the local varieties Primoz adopts a holistic approach to farming and winemaking. He grows varieties that originate in Vipava Valley and along the northern Adriatic coast, namely: Zelen, Pokalca (Schioppettino), Refošk (Refosco), Rebula (Ribolla Gialla), Malvazija (Malvasia d`Istria), Laški rizling (Italian Riesling, Welschriesling), There is also some Modra frankinja (Blaufränkisch), whilst he inherited a vineyard of Modri pinot (Pinot Noir) that has become his not-so-secret-passion (as a committed Burgundo-phile).

The diversity and richness of the vineyards is impressive. He believes that a thriving microflora are an integral part of each vineyard’s identity and encourages their proliferation by practicing organic and biodynamic farming. He appreciates the nuances of soil type and climate diversity in individual locations, and farms accordingly.

The eggs are accumulating at Burja

In the winery Primoz only controls a few things such as temperature and the degree of oxidation in the cellar. He allows spontaneous fermentation and ensures contact between grape skin and must with the white wines. The diversity of yeast strains contributes to the complexity of the wine and provides an original expression of each vineyard.

The vineyards have their roots in sedimentary flysch, the composition of which differs significantly according to lithologic varieties of the bedrock below the soil. In Zadomajc and Ravno Brdo sandstone and marlstone form the bedrock. Marlstone prevails a little, causing middle heavy ground, which retains moisture quite well. It is a similar situation in Stranice, except that marlstone is even more prevalent over sandstone, resulting in even heavier and wetter ground. In the biggest vineyard in Golavna the soil lies over tough sandstone, is thinner, lighter and dries faster.

The two baby wines are in stainless tank, one being a Vipavan version of Malvasija, the Istrian grape. This Petite Burja is from the youngest vines – it’s simple and clean. The other little wine comes from Zelen, the pride of Vipava. Also young vines, also maturation in stainless steel tanks. Reminiscent of citrus and apples, with undertones of green herbs, particularly sage, it is elegant and delicate on the palate, while rich and harmonious. Somewhere between a Muscadet and a mini-Vitovska.

Burja white is the heart of their production, based on the former glory of the Vipava white wine, Vipavec (win von Wippach). This blend comprises Laški rizling (Italian Riesling, Welschriesling) 30%, Rebula (Ribolla Gialla) 30%, Malvasia 30 %, other varieties 10 % and is a field blend of the two oldest vineyards: Ravno brdo over 20 years old and Stranice over 60 years old with the different vines growing side by side. This wine is aged for one year in foudres of 20 – 35 hl.

Burja noir is the aforementioned Modri pinot (Pinot Noir, Blauburgunder) the only non-local variety in the vineyards, though historical records suggest that Pinot Noir has been already present in the Vipava Valley for many years. Primoz’s version is aged for two years in large barrels (10 to 15 hl) and 225 l barriques.

Burja Reddo sees Primoz playing with the idea of former red wine varieties in the Vipava Valley, which were once in minority. Pokalca (Schioppetino) 50%, Modra frankinja (Blaufränkisch) 30% and Refošk (Refosco) 20% make up this red blend, the grapes coming from young vineyards, from 4 to 6 years old. Also aged for two years in large barrels (10 to 15 hl) and 225 l barriques.

To be continued…

Congratulations for this excellent and comprehensive presentation of the country and of one of my favourite winemakers. Looking forward to the sequel.