What constitutes a great wine is always a subjective judgement. Each individual arrives at their own very singular list of best—or favourite—wines. It may that one transformative bottle that you had at a special moment; it opened your eyes, your palate, your heart and your mind, to new possibilities and wonderful aroma and flavour sensations. It may be a wine that consistently delivers high quality and that you recognise (and search for) something intrinsic to the wine.

It must possess a life, a power, an energy, whatever we wish to call to it and this is the catalyst that provokes a more engaged response.

I explain some of the criteria that I use for inclusion in this list on a previous ‘intro’ post. One of those that I would reiterate is that I enjoy being taken unawares. Surprise is (surprisingly!) primal—it puts us into a state of excitement and uncertainty, it is an integral part of so many wine epiphanies. After the surprise comes either the acceptance, or rationalisation of, the experience, or to put it more bluntly either going happily and uncritically along with the flow of drinking the wine, or desiring to investigate what properties the wine possesses that it so aroused your intense response to it.

In most of the following examples, I am thinking of a particular bottle, normally the first intimate encounter with the wine in question. The context provides you the preconditions for the experience: where you are, who are you are with, the food, how hungry you are, the light, the weather, and just how you feel on the particular day. As no set of conditions can be identical, then the wine must also be something more that we can pour our ephemeral moods into. It must possess a life, a power, an energy, whatever we wish to call to it and this is the catalyst that provokes a more engaged response.

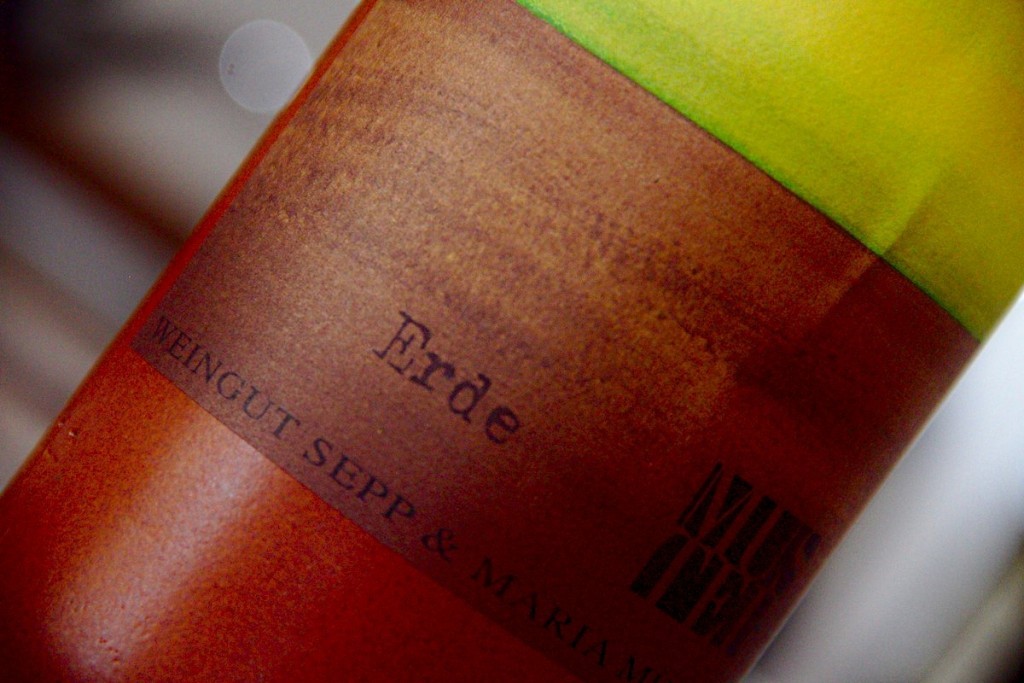

ERDE

Maria & Sepp Muster

Earth Canal

Erde means “earth”, and this resonant amber wine is housed (and liberated) in a beautiful clay bottle adorned with the striking labels based on the work of artist Beppo Pliem, a dear friend of the Muster’s, who just before his death, created a series called “More and more of less and less”, and whose paintings express the natural interaction between the earth, the sky and the vine. The farming is watchfully and respectfully biodynamic, the vine-training done according to traditional local methods, the Styrian climate marginal, the soil a lime-rich clay opok, the altitude 450 metres, and the grape Sauvignon with a little bit of Chardonnay. A maceration of twelve months, and a rich and varied fermentation and maturation process in Pauscha barrels, alternating between reductive and oxidative, gives this wine its profound, almost perpetually shifting, character. As Sepp himself says: “Our way of working is very free and engenders lots of uncertainty. Nature is not always predictable, and follows its own laws. It’s a good thing, as too much certainty clouds our vision of opportunity, and impedes change. The advantage of this uncertainty is that it gives the wines a strong personality, full of vitality and meaning.”

This soaring earth-wine is nurtured both by the minerals within the soil and the light from the sky.

Although I had drunk the wine on several occasions, I had never experienced it through someone else’s eyes and been so receptive to its complexities.

“I asked her if she was amenable to trying an unusual wine. She declared herself willing and so I ordered – and we drank – a bottle of Sepp Muster’s Erde from southern Styria in Austria. I can only describe the experience as beautiful, for the wine took us on a wonderful sense-ravishing journey. Erde, maybe, but Himmel in the glass!), Initially, it detained our attention with its striking orange colour, inviting us into a nose hinting of orange blossom, elderflower, wild mint, golden plum and apricot skins. The wine had moved by the second glass, its palate revealing honeydew melon with delightful pickled ginger and dried cumin, then changing once more slowly becoming leaner and more reserved, impressing now on the stones and mineral salts (the opok showing through here). By the final glass the Erde was tightly wound, more intense and spicier, the minerals shooting through the fruits themselves. My companion and I looked at each other and simultaneously mouthed the word: ‘Wow’.”

Such experiences mingle beautiful hilarity with clarity in a kind of epiphany. The wine exudes glamour, charisma, celebratory joyfulness. We owe it to ourselves (as well as to the vigneron and her wine) to be receptive. Increasingly, I try to experience wines more completely, by not insisting but rather sensing them, not itemising my impressions as if I were searching out a shopping list of qualities, but casting judgement aside, tasting inside out, exploring personality, viewing flaws as textural variations within the whole rather than diminishing faults. I want to dive into the internal story, engage with origin. I am into mutability and playfulness on occasions. I like simplicity and singularity, wine as haiku, the miniature of grace and purity. I like structure, but I don’t always need structure. Wilfulness is also fine. Energy, tension, cut and crunch. Juice gushing over my tongue. All this.

This soaring earth-wine is nurtured both by the minerals within the soil and the light from the sky. Its colour is expansive, shiny and amber, its structure strong, its finish saline. One tastes nothing other than what is integral to the wine. One tastes much, but one tastes that less is more. Words are not enough.

Why we love it: A strong nourishing wine from a deep place that you want to take time to develop a relationship with. Its glorious colour that radiates energy. That bottle.

GREEN DRAGONFLY

Andreas Tscheppe

Dragonfly’s den

One of the Andreas’ key vineyards is the south-east facing high-altitude Krepskogel. The steep terraces lie 500m above sea level and are surrounded by thick forests. You are but a hop from Slovenia – indeed one drives across the border to reach the vineyard from Andreas’ house. The soil here is very sparse and dominated by blue opok with lots of stones on the surface. The remarkably high mica content is seemingly responsible for the particular graphite scent of the wines.

Farming is biodynamic. Each plant has its place and every living thing is taken into consideration in the belief that the vitality and complexity of the soil are the basis for expressive wines. It is an invigorating place to visit in season, full of colourful wild flowers and insects. Andreas speaks about the dialogue of the earth and the air and one may see the roots of the newly-planted vines here peeking out and being part of the conversation. Strike two stones together and smell. Blue opok – a gunflint aroma, a miniature detonation, the kind of fireworks we smell and taste in the wines.

Here Andreas grows and harvests his grapes for the Green Dragonfly (Sauvignon), the Segelfalter (Gelber Muskateller) and Schwalbenschwanz (Gold Muskateller). Close your eyes and smell these wines – light, herbs, flowers, earth and stone captured in the different liquid form.

Green Dragonfly, that Sauvignon, is bursting with kinetic life, an aromatic explosion of minerals and herbs. Despite its tongue-coating thickness, it is cool and focused with a touch of matchstick reduction giving it an edge. When one tastes, one can visualise Andreas Tscheppe in his vineyards hotching with fauna and flora, grasses, weeds, herbs, dragonflies, his eyes darting, alighting on a certain grape bunch, touching, feeling, plucking. This thrilling nervous vitality communicates itself seamlessly into the wines.

The same vineyard yields two other wines: Segelfalter & Schwalbelnschwanz. There’s Muscat and Muscat and there’s Tscheppe’s versions. The former, a Gelbermuskateller gets your superlatives juicing, whilst the skin-contact Goldenmuskateller will leave you on your Hosenboden!

Two utterly “butterfly” wines these, aromatic yet wild and herbal, with firm-fleshed yellow-leaning-into-gold fruit flavours and bitter quinine notes. The Gelbermuskateller is a long-established variety in southern Styria. Muscat wine seems to thrive on the Krepskogel. Its exceptional flavour spectrum combines the exotically floral with beautiful notes of white and yellow peach, pink grapefruit and white spice. The finish is dry yet tongue-enveloping, ripe fruit offset by refreshing bitterness and wild herbs.

Close your eyes and smell these wines – light, herbs, flowers, earth and stone captured in the different liquid form.

The Goldmuskateller grape originates in the South Tyrol. Tscheppe brought this grape variety back to Styria and planted it on the Krepskogel. In its youth the strong tannins from the three weeks on skins make this wine taut and tart, which is part of the charm! The flavours play like an orchestra from your nose to your palate, the length is endless, the fruit darting out from the smoky-spicy ensemble.

All this shows that the grape variety is the transmitter for the vineyard – and what a vineyard. Andreas belongs to a group of five growers who operate under the banner Schmeck das Leben (taste of life). His dragonflies and butterflies are wines as natural life, as if the grapes had inhaled their living environment.

Why we love it: We see that Sauvignon can reach another level when the farming is exacting, when the environment is healthy, when the grapes are sorted in the vines and hand harvested at maximum ripeness and when the naturally-oxidative elevage occurs over a long period of time. The interplay between reduction and oxidation is an eloquent dialogue.

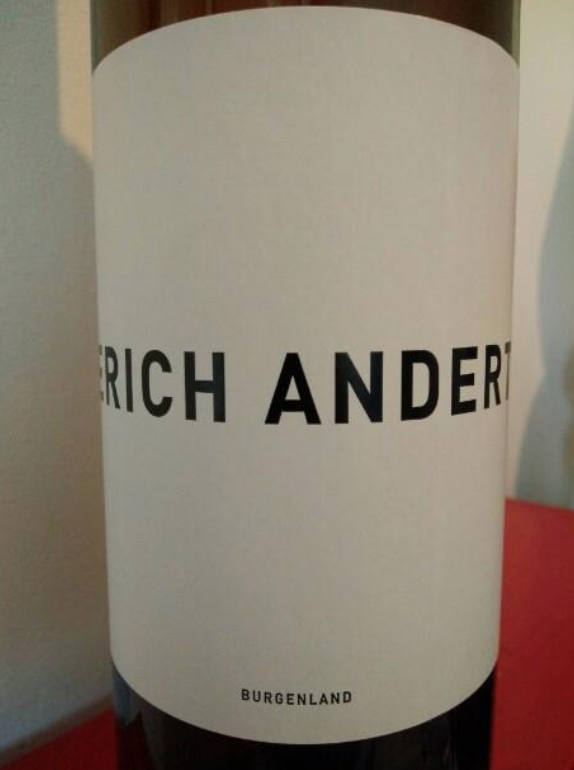

“PM”

Andert-Wein

Energy drink

PM stands for Penetranter Mistkerl, as in a total bloody nuisance, or Puligny-Montrachet, as the Anderts call it (ironisch gemeint) or, as we know, the secret grape, alias Petit Manseng, that somehow made its ironic way from the footslopes of the Pyrenees to the flatlands by the Neusiedlersee.

Michael Andert was born into a large family and grew up on a farm with mixed agriculture, livestock and viticulture and learned to respect his family, his animals and the associated work. Today, as winemaker, this respect has deepened even more. “We think we found the right way in the biodynamic economy to press the grapes into sustainable and valuable wines. We respect the earthly and cosmic influences on our wines, our soil and, also we respect the influence of the seasons on our wines.”

Talking to natural growers, it’s clear that they view treating the vineyard as a living organism, as well as working without chemicals or additives in the winery, as a prerequisite for making quality wine. There is a certain Occam’s razor logic to this approach –that by not over-complicating procedures you arrive naturally at a truth-in-wine. Biodynamics is predicated on observing and responding to the needs of the vineyard rather than following a prescriptive course of action. Working responsively in the vines tends to be mirrored in the actions in the winery. Knowing what you have (in the quality of grapes) means that you tend to do what you feel is right. It is not pure science – there is intuition, gut instinct, feel and taste.

Michael is a farmer. He is as proud of his livestock as his vineyard. He strides, even bounds between the vines, taking deep breaths as if he wanted to inhale the entirety of his surroundings. He has also created a garden, one exploding with flowers and plants. A narrow path wends serendipitously through clumps and clusters of undergrowth, across little wooden bridges over small ponds populated with frogs. We wander by some beehives and discover little clearings populated by strange mud and stone creatures and poppets. Cow horns are ubiquitous – the symbols of fertility are rife. Occasionally, one will find an improving text from Goethe or Confucius nailed to a fence post, jolly exhortations, hailing and hugging nature. A harbour for wild life rather than a monoculture of grape growing the vineyard is part of this celebration. And it is so much more. Andert makes his garden an everywhere and reminds one that nature is therapeutic. Medicines are made from extracts of herbs and plants, and victual nourishment too, and, of course, there is the wine – one cannot but laugh with pleasure at the sheer loving immersion in a place that is humming on every level.

A burnished sunset of a wine, its deep hues are captivating, glowing, almost throbbing with primal energy.

What a wine this is. A wine “of the balcony” to catch and squeeze the post meridian blood-orange essence of the dying light. The colour seems to be changing subtly by the moment as if animated by a response to the very light of the day. A burnished sunset of a wine, its deep hues are captivating, glowing, almost throbbing with primal energy.

The nose, or whatever we choose to call it, is (sweet)meaty and a little bit smoky, the palate is smooth and almost velvety with suggestions of pink grapefruit, yet also salty with a bitter almond note on the finish. A wine that sits on the mother of lees and skins, starts off tightly wound in its own skin, its aromatics initially reserved, then gently exudes a kind of warmth as of orchard fruit baked with sweet spices in the oven. And all Andert’s wines have a faintly medicinal bitter, fennel-inflected after-taste. This may to be do with the fact that the vines share their space with wild fennel and many other plants and herbs that have the same anise profile. They also possess what we like to describe as “natural energy”. Easy in themselves or with a relaxed intensity, not inviting judgement, but utterly and vitally redolent of the vineyards from which they are born.

Only 200 bottles of this nectar are made.

Why we love it: Because we smell the life of the vineyard in it, a place where there is a constant interaction with nature. Because the wine is exotic, vital and wild and because of skin-contact, where the al dente bitter texture gives definition to the whole.

FELDSTÜCK RIESLING

Matthias Warnung

Breaking the Riesling code

In Lower Austria there is a divide between Riesling and Grüner Veltliner wherein the former is broadly planted on primary rock and the latter on loess which confers Grüner Veltliner with the wherewithal to make creamier, fatter, richer, and more immediately fruity wines.

Kamptal is subject to the binary effects of the hot, Pannonian plain heat from the east and the cooler Waldviertel region towards the north-west. The unique combination of warm days and cool nights contributes to the fine aromatics and naturally-retained vibrant acidity in the grapes.

The wines from this region have been pretty straitlaced in the past, the winemakers sticking rigidly to a formula to make commercial, filtered and sulphured wines. A select few young vignerons escaped the region and its recent traditions in order to challenge themselves. Their experiences with alternative wine cultures in other countries allowed them to return with a totally different mind-set.

Mouth-filling, layered, notes of dry honey, creamed pear and golden plum, carried by effortless acidity and finishing with subtle tannins. Riesling, but not as we know it.

Matthias Warnung is young chap who has worked several vintages with Craig Hawkins (Testalonga) and Jurgen Gouws (Intellego) and is influenced by their can-do natural approach. He is not dogmatic, but a possibilist, exploring his own path whilst remaining very focused. (He would like to plant Poulsard and Harslevelu!). Like Craig, Jurgen and Tom Lubbe (another mentor) Matthias is looking for vivid acidity and a linear dimension in his wines. In his atmospheric underground cellar, we tasted only from tank and barrel. He makes one of the best dry rosés I’ve tasted from the Zweigelt grape, three Grüners (including one with a short period of skin contact) and a beautifully-balanced Riesling.

Matthias may look youthful but he exudes self-assurance. He loves hard-work, relishing the challenge of setting up new vineyards to give him the material he needs to make convincing wines. His palate is shaped wines to respond to edges and angles. In Kamptal (even more so in Wachau) wines are expected to have weight as if that is a sign of innate seriousness. The patience of slow elevage finds its true reward. The natural approach is an evolving one, a tweak here, a change there, always following the vintage and the quality of the grapes rather than pushing the wine to conform to a certain template. Matthias’ Feldstück Riesling is fermented whole bunch in tank with a 12-16-day maceration on the skins, before being matured in three-year-old 300 and 500-litre barrels for up to a year before being bottled without filtration, fining and only a little sulphur (25 ppm) added. It undergoes full malolactic conversion in the barrel. Mouth-filling, layered, notes of dry honey, creamed pear and golden plum, carried by effortless acidity and finishing with subtle tannins. Riesling, but not as we know it.

Why we love it: Because it is a wine that is comfortable with its phenolic structure, that takes the aromatic charm of the variety, and builds with layers of fruit and lees.

*

Interested in finding more about the wines mentioned? Contact us directly:

shop@lescaves.co.uk | sales@lescaves.co.uk | 01483 538820