New Zealand is viewed by many and sundry as the Land of the Long White Sauvignon, a drink on the river gravel rocks topped with mint and elderflower pressé. Les Caves, however, dwells in a world of pleasing uncertainty, a world where jokers and yeasts are wild, liquid is invariably turbid and critical opinion is a zero-value currency.

Whether it is still a hangover from the dairy industry (that’s not a sentence you read every day) winemaking in NZ tends to favour cleanliness over godliness. Anaerobic stainless commercial yeast-profiled wines, largely intended for export, are manufactured. And brand NZ hits its benchmarks, repeatedly dialling up the numbers on the gooseberry Sauvignon and chocolate cake Pinot Noir. The words Marlborough and Sauvignon are as mother’s milk to the sommelier in the street. Whilst that might be a simplistic summary of the NZ scene, the wines have become generic to the point of being stylised, trading on their broad certainties, rather than constituting a real wine identity. A country’s wine culture develops roots when its vignerons acquire the confidence to make and sell wines that they themselves find pleasing, or when they respect and communicate their terroir, or allow their wine a certain freedom.

In terms of the competition, Australia has a dynamic wine culture driven by growers, sommeliers, restaurateurs, importers and wine writers. This natural wine culture communicates in a friendly (and a proactive) way with its audience and informs the eating and drinking in that country. South Africa, meanwhile, is on the cusp of change – there is a strong core of young adventurous (well-travelled) vignerons who want to make the wines they want to drink. These guys have formed a support network and happily exchange ideas. It is difficult to discern the same progressiveness in NZ viniculture – there is some excellent vineyard practice and some shining examples (one thinks of Millton Vineyards) but little in the way of handbrake-off winemaking.

The reference is Pyramid Valley Vineyards where beautiful biodynamic farming meets intelligent and intuitive natural winemaking. These are beacons of purity – the home vineyard wines exhibit brilliant terroir definition and contain a mineral core that only sympathetic and patient winemaking can elicit (these are “slow wines” in the truest sense). Vigneron Mike Weersing also makes skin contact wines which are rather fine.

If Pyramid was the lone voice for several years now there are few extra hazy diamonds in the ruff. The beauty of the natural wine world is that it is a wild ferment of ideas and what-ifs. Winemakers travel, observe and absorb, and apply what they have learnt to their vision of the world. Having company on the journey is also an encouragement to push for what you believe in. Mike and Claudia’s achievements have inspired – and will continue to inspire – others.

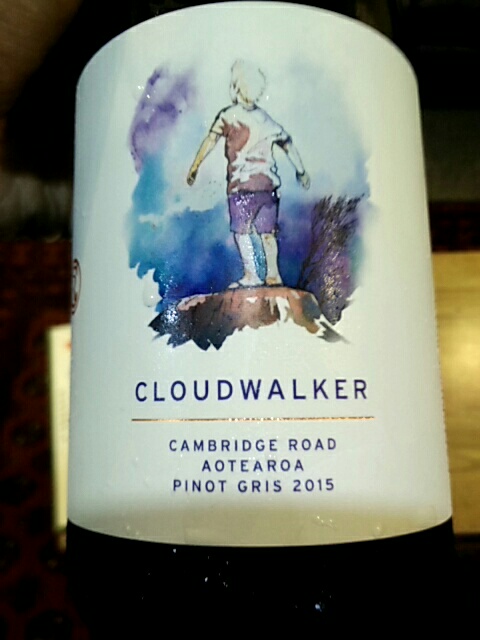

The NZ World According to Gris

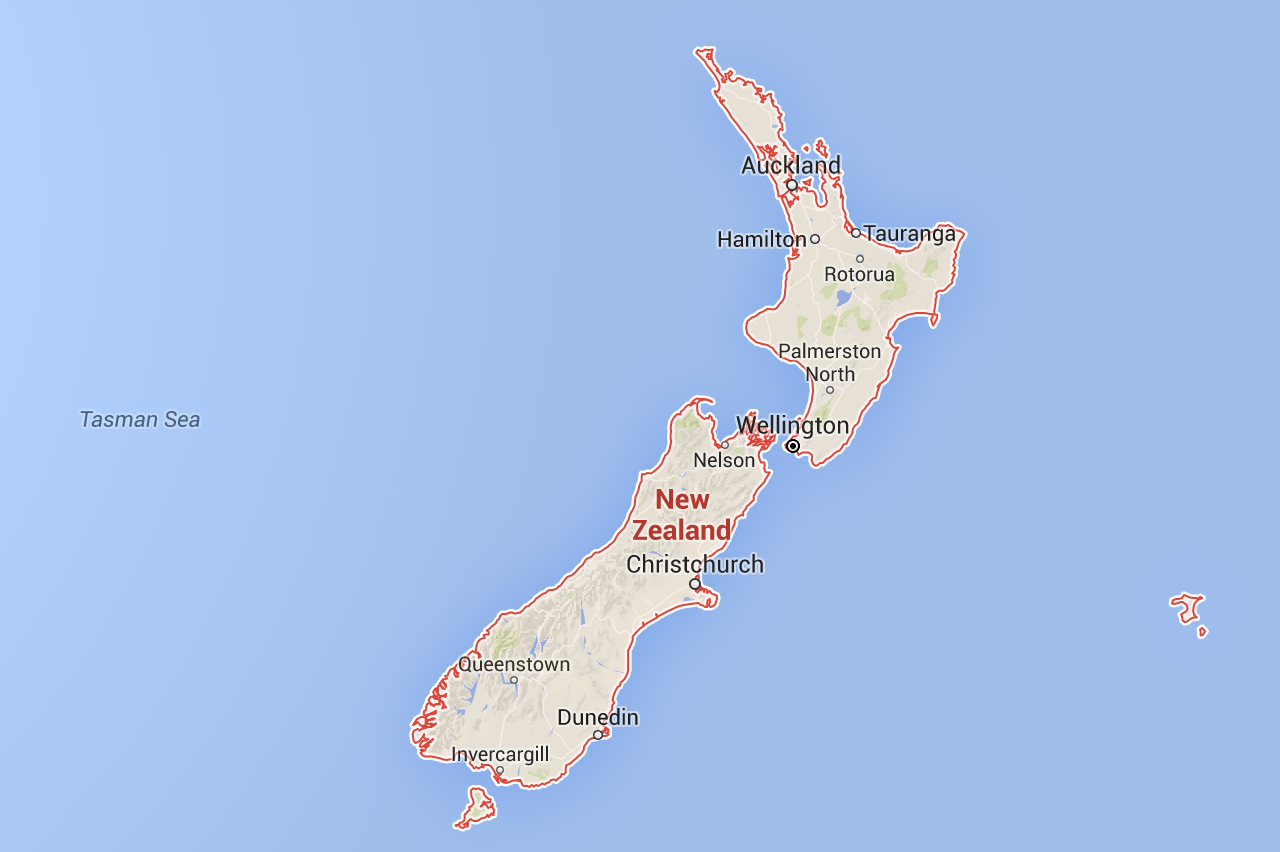

Lance Redgewell’s Cambridge Road Vineyard is a small 5.5-acre estate in the esteemed Martinborough Terrace Appellation in the North Island of New Zealand. He and his team are the newest stewards of this vineyard, which was first planted in Pinot Noir and Syrah in 1986 which makes the vines amongst the oldest in the country and they continue their management with love and pride, focusing their time and energy on cultivating the land according to natural biodynamic principles. Lance embarked many years ago on understanding the grape vine in its natural state and how as a grower he could allow the vine to flourish with only the assistance of natural encouraging inputs. “It brings me closer to the land than ever before and I believe it brings a quality unsurpassed by other means of agriculture when conducted correctly and intelligently.”

We have witnessed a development in the wines themselves. Each year they acquire more of an edge, are less polished and correspondingly more drinkable.

And so to Cambridge Road’s Cloudwalker, made from hand-harvested Pinot Gris and 100% whole bunch wild fermented in neutral oak barrels (228-700 litre). The wine was macerated with stems for 3 days prior to basket pressing with foot treading to extract a little more colour. No filtration, fining or SO2 added, a zero additive wine based on lightly skin soaked Pinot Gris, the intention to deliver the true nature of Pinot Gris from the stony soils of the Martinborough region. Early spring bottling has allowed a natural sparkle to be retained adding a refreshing dimension to the palate (Cloudwalker is bottled under crown cap).

With its light orange-hue Cloudwalker has a fresh peach-skin texture. Cider House rules here, an irresistible combo of russet apples and ginger beer, the gentle spritz providing a thirst-quenching rasp.

This wine has a red brother, a blend of Pinot Noir and Syrah across two vintage, a mixture of whole bunch and destemmed fruit, young vines freshness meets old vines minerality. Also crown-capped the wine shows a new direction for New Zealand reds, one where the wines are less “earthbound”, for want of a better word and may be bright, energetic and uplifting. Cloudwalker indeed.

The Don is run by Alex Craighead and Josefina Venturino who have settled on a new vineyard located in Upper Moutere in Nelson. The vineyard has been certified organic since 1997 and as such is one of the oldest organic vineyards in New Zealand. The Don consists of only 4 wines, two Pinot Gris and two Pinot Noirs. The idea is to illustrate the difference of the terroir from Nelson and Martinborough, the Nelson soils being all Moutere clays which are the oldest and poorest soils in New Zealand, whereas the Martinborough vineyards are from old free-draining river gravels. The wines are made the same way with just the sites changing.

In an age of manipulation and science these wines are a product of the “unlearning” of much of what Alex was taught in his studies and work experiences. These are “living” wines and will evolve from every tasting.

The Pinot Gris is from hand harvested, 100% destemmed fruits and spends 30 days on skins. The winemaking is natural using indigenous yeasts with the ambient ferment taking place in a mixture of barrels and tinajas (200-250L). The win undergoes a natural malolactic; there is no filtration, fining or sulphur used at all. Alex Craighead is a young vigneron who has travelled around the world making wine in various countries (including Japan). He has an intellectual approach to the subject, but through experimentation finds that his wines express themselves most resonantly without the addition of sulphur.

Those who think orange/skin contact wines taste the same, think again. Parenthetically speaking, we don’t say that red wines taste the same because of skin contact so why do certain people level the charge at so-called orange wines? The Cloudwalker is from gravels and loess, whole bunch, short soak and bottled with its latent gas, is crunchy fun. The Don Pinot Gris from old clay soils, is deep amber, richer, spicier, a touch more oxidative (notes of butternut, roasted yellow spices) and needs time in the glass to open up and reveal its true (multi)colours.

Like London buses, skin contact Pinot Gris from New Zealand tends to come in threes (in the wacky world of Les Caves de Pyrene). And now we move the carnival of single grape varieties down to Central Otago to meet the Satos.

Sato Wines was established by Yoshiaki Sato, and his wife, Kyoko Sato, as a small project in 2009. Starting with 190 cases of Pinot Noir in 2009 vintage, Sato Wines now also deals with a small amount of whites, Pinot Gris and Riesling as well but the annual production of the company is still around

Kyoko and Yoshi met in 1998 at a Japanese bank, where they were working. After 12 years of work at the bank in Tokyo and London, they moved to New Zealand in 2006, aiming eventually to make their own wines and both studied for graduate diploma in viticulture & oenology at Lincoln University in Christchurch. Immediately after graduation, they settled in Central Otago and started their winemaking careers. After working at Felton Road with Blair Walter for 2.5 years in the vineyard and cellar, Yoshi worked at Mount Edward as the winemaker for Duncan Forsyth for 4 years. Now he’s making Sato wines at Rockburn Winery in Cromwell, together with working at the organic contract vineyards. Kyoko works in the vineyard of Felton Road as a vineyard supervisor besides running Sato Wines.

Based in New Zealand, they have also worked in the traditional winegrowing countries as well in the last several years, doing time with the who’s who of the natural wine world. Yoshi worked with Bernhard Huber in Baden, Germany in 2007, Tom Lubbe (Domaine Matassa) in Roussillon and Jean-Yves Bizot in Vosne Romanee in 2008, Jean-Pierre Frick in Alsace in 2009 etc…Kyoko worked with some natural wine producers in France as Phillip Pacalet (Beaune), Julien Guillot (Macon), Christian Binner (Alsace)…

We are concerning ourselves not with the straight Sato Pinot Gris but with the wine called Pinot Gris L’Atypique.

This starts already out of the box by being a blend of Pinot Gris 85%, Riesling 15%, although this is not so crazy when you think of the respective characteristics of these two varieties.

The grapes were all destemmed to a small open top fermenter- no enzyme, no additives and no SO2 added before and during fermentation. Pre-fermentation soaking continued for several days. One remontage was done at the end of pre-soak period. After pressing the wild ferment starts (with the occasional punchdown) and continues for 2 weeks. Then, the fermenter was closed with a lid and the wine was soaked on skins for two and a half months. The wine does its malo, spends a further ten months in used barrels and tanks and is bottling without filtration, fining or SO2.

In a country where the rush to get white wines into the market means that they barely finish fermentation before they are bottled, this is a wine that spends 15 months on the lees, not to mention the extended period on the grape skins. What you get in the end is something quite unique and magnificent; multi-layered to the point of great complexity, rich in warm beeswaxy orchard fruits, spices, herbs and tannin.

To say that these three wines are not typical misses the point. They are the products of their respective origins in three different parts of New Zealand (different soils, different climates). They are all the result of excellent hands-on organic or biodynamic farming and very low yields (30-35 hl/ha). They are all natural ferments –the core flavour is generated by the grapes and their own yeasts rather than a commercial yeasts, tank aromas and SO2. The vessels allow for micro-oxygenation during the long ferment (old barrels and amphorae). All the wines soak up goodness and energy from the skins; this gives the juice its spicy intensity and a touch of tannic astringency. These are real wines, living paradoxes in that they are both atypical (unique) and yet entirely typical (true to origin).