Styria – History and Regional Overview Viticulture is one of the oldest cultural traditions in Austria. As early as 2500 years ago (about 400 BC), the Celts knew about and availed themselves of the grapes that grew wild in this region. But it was the Romans, of course, who first cultivated extensive vineyards. Evidence of the Roman wine culture is shown by the findings of vineyard remnants and drinking vessels in southern Styria. Viticulture was neglected during the Dark Ages but did not completely vanish. A new impetus for wine growing in Styria was given by the introduction of Christianity and cultivation of the land. It was an important economic factor throughout the Middle Ages, vine cultivation reaching its high point toward the end of the 16th century, whereupon another phase of neglect followed due to plagues and wars. Archduke Johann was responsible for the resurgence in Styrian viticulture with his concern for systematic improvement and development in the early 19th century. He created an experimental vineyard with 425 different varieties. There was, however, a further serious setback in the second half of the last century owing to devastation of the vineyards due to diseases and pest at a time when Styria was one of the most important viticulture regions, with vineyards covering nearly 35,000 hectares. Currently 4.200 hectares are under cultivation as vineyards in Styria. Which means in bald figures that Styria has about 9 % of the total vineyards in Austria and produces a little more than 7 % of the country’s wine. The vineyards generally make use of dry, stony and steep slopes that otherwise would probably not be cultivated. Over the half of the Styrian vineyards have a slope of more than 26%, so that they are quite properly called mountain vineyards.

Southern Styria feels like an artisan wine region. These vineyards are generally small operations, of which there are some 3.000. The average vineyard covers only 1.40 hectare. About the half of the wine that is drunk in Styria is also produced there, so there is no danger of overproduction. In order to survive in the face of the competition created by the larger wine-growing provinces in Lower Austria and Burgenland, the Styrian producers have successfully concentrated on producing wines of unusual quality.

Southern Styria feels like an artisan wine region. These vineyards are generally small operations, of which there are some 3.000. The average vineyard covers only 1.40 hectare. About the half of the wine that is drunk in Styria is also produced there, so there is no danger of overproduction. In order to survive in the face of the competition created by the larger wine-growing provinces in Lower Austria and Burgenland, the Styrian producers have successfully concentrated on producing wines of unusual quality.

White grape varieties dominate the vineyards in southern Styria in particular. Sauvignon flourishes on the opok soils. Harvested mid-late October, it is fuller and richer with less pronounced fruit character and more on the texture with notes of fennel and dill on top of ripe citrus and apple.

Chardonnay, known locally as Morillon, is understated yet consistent, sometimes vinified to be on its own, sometimes blended with other white varieties. Without the cushion of new oak it displays gentle flavours of waxy citrus, pollen and toasted oatmeal. Weissburgunder has good depth with warm spicy butternut texture and tends to ages well. Welschriesling is the wine of green apple and lemon fruit for early drinking with Gelbermuskateller (Moscato Giallo) a delightful floral alternative. Produced in tiny quantities, Goldmuskateller, however, is the gold standard with a shimmering array of honey, grapefruit and warm spice. Andreas Tscheppe’s version of this, called Butterfly, is a wonderfully exotic and hedonistic wine.

Chardonnay, known locally as Morillon, is understated yet consistent, sometimes vinified to be on its own, sometimes blended with other white varieties. Without the cushion of new oak it displays gentle flavours of waxy citrus, pollen and toasted oatmeal. Weissburgunder has good depth with warm spicy butternut texture and tends to ages well. Welschriesling is the wine of green apple and lemon fruit for early drinking with Gelbermuskateller (Moscato Giallo) a delightful floral alternative. Produced in tiny quantities, Goldmuskateller, however, is the gold standard with a shimmering array of honey, grapefruit and warm spice. Andreas Tscheppe’s version of this, called Butterfly, is a wonderfully exotic and hedonistic wine.

The red grapes are less exalted in this region but still make very drinkable wines. Zweigelt is rustic with exotic spice and floral character with predominant aromas of cinnamon and violets. With age it becomes more complex and finer. Imagine a spicier version of Beaujolais or an unoaked red from Galicia. It works well in blends too. Blaufrankisch is a late-ripening red and tends to produce deeply coloured wines with dark fruit aromas, peppery spice notes and moderate to high acidity. Depending on where it is produced the wine can be unoaked, or spend some time ageing in the barrel. The unoaked styles tend to be lighter bodied while the oaked versions tend to be of fuller body and often rather bloated. Not much is produced in southern Styria. Blauer Wildbacher is a dark-skinned grape variety and specialty of the Styria region of Austria. It is a very old variety said to date back to the Celts, and manuscripts first record the name in the 16th century. The variety is not particularly demanding in terms of soil though it does require warm sites with sufficient aeration as it is prone to rot. The grapes tend to ripen late and yields can be inconsistent. Wines made from Wildbacher typically exhibit red berry and herbal flavours with a refreshing acidity. Genuine Schilcher comes exclusively from West Styria although this style of wine is also made in South Styria and Southeast Styria. Schilcher wines are rosés with pale red to straw shades and true Schilchers from West Styria can be identified by the presence of a Lipizzaner stallion on the bottle or cap. Schilcher wines are light, dry and fruity with a distinctive crisp acidity and should be drunk as young as possible.

Meet The Strohmeiers

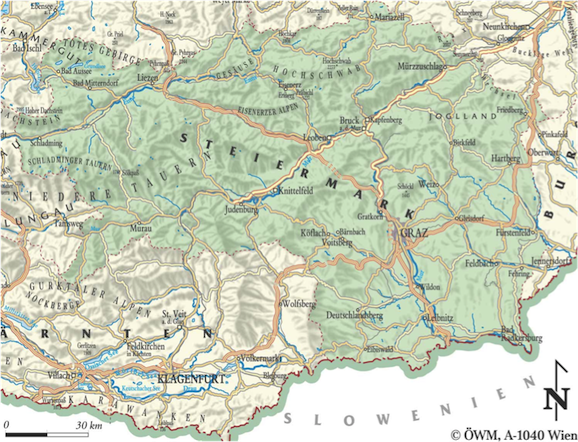

After taking an initial wrong turn onto the A4 autobahn instead of the A2 – Bratislava anyone? – before flipping back and proceeding Graz-wards, we circumnavigated Austria’s second city and followed Christine Strohmeier’s precise and super-helpful instructions, wending our way through a succession of shortbread tin villages till we reached the tiny hamlet of Lestein and the sign for Strohmeier. We were greeted by Christine, and after an initial refresher glass of Schilchersekt served in enormous Burgundy balloons (which tasted a little like fizzy Campari) we walked over the road with Franz to take a gander at the local vineyard. As with many of the vineyards in Styria it angled steeply from the top of the hill into the valley below and the ground bore testament to the effects of two months of incessant rain being almost boggy underfoot, whilst the ravaged vines themselves told a similar story sporting small sporadic bunches of still unripe grapes. The vineyard itself was full of flora, carpeted with a lush layer of tall grass, weeds, wild herbs and flowers. Franz dug into the soil and demonstrated the quality of the humus, a sweet-smelling friable soil full of worm and bug life. He then took a handful of earth from a row where a tractor had been driven. This was more compacted, stale by comparison, although healthy by the standards of most conventionally-farmed vineyards. Some swift factual context. The Strohmeier winery is located near St.Stefan/Stainz in the West Styrian wine region, technically in the south-eastern foothills of the Alps at the base of the Koralpe Mountain. The climate is called “Illyrian”, wherein cool air-currents from the Koralpe mountain range brings regular rain. (Normally, this part of Styria would receive 1,000 mm per year. 2014 was not a typical year!) Meanwhile, the intensity of the sun warms the vineyards and supports a long growing season with slow and sustained ripening of the grapes. Harvest usually takes place between mid to end of October. Strohmeier’s vineyards are scattered in a few small parcels. The home 3.5 ha vineyard in Lestein is planted to that regional specialty Blauer Wildbacher. The soil is composed of ochre-brown sandy clay with iron from Opok and subterranean gneiss. Another vineyard is in Stainz, a 2 ha south-facing plot on Stainzer plate gneiss with an active mineral content. The elevation is slightly higher here and amongst the variety of grapes are grown are Sauvignon, Weissburgunder, Zweigelt, Blauer Wildbacher, Chardonnay and Muskateller. Finally, there are a couple of vineyards n Bad Gams with various orientations (east to south and south west). These have the highest elevation (over 500 metres) with a full gamut of grapes planted. This is historic wine country. There are records documenting the vineyard in Lestein back to the 14th century. In Stainz we were shown an old cellar with local vintage wines dating back to 1938. Franz mentioned that he had opened a wine from the 1950s that was not only in good condition, but when opened (and accidentally forgotten about) had improved after several months.

After our earth-tutorial we repaired to the winery for dinner. Christine cooked course after course of beautiful vegetarian food including a terrine, tart, salad, home-baked bread (sour dough rye, natch). We then descended into the basement cellar, the walls of which are adorned with Christine’s vivid paintings, to taste a range of wines from cask.

After our earth-tutorial we repaired to the winery for dinner. Christine cooked course after course of beautiful vegetarian food including a terrine, tart, salad, home-baked bread (sour dough rye, natch). We then descended into the basement cellar, the walls of which are adorned with Christine’s vivid paintings, to taste a range of wines from cask.

Franz is not so much trying to bring the philosophy to the wine as the wine to the philosophy. He has embarked on his own natural path of discovery and self-discovery. The wines will not flatter our preconceptions – our tasting requires us to engage our palates and accept new registers of texture and flavour. All the wines possess a bitterness verging on the astringent, yet with an evenness in the mouth as if the matter and energy in the wine has been equally distributed throughout every molecule of liquid. When you taste a wine normally you are able to break it down into discrete components – here is the fruit, there the acidity, and in that direction the tannin. This diffusion is less applicable with natural wines made in this uncompromising vein – the whole is greater than the sum of its part and it’s a pretty solid whole. The wines thus do not yield readily to blithe dissection.

We first assay various degrees of sekt from younger frizzante perky pink styles to the substantial older darker-red vintages in the TLZ range. Whites include a very good Weissburgunder and there a couple of striking orange wines, one called Sonne No 3 (one month on skins), the other aptly called Orange (nine months on skins). The aromatics are lovely here, Sauvignon lends itself to short and long periods of skin contact. A Zweigelt/Wildbacher blend called Rot No 5 and an intense Rotsekt are also part of the line-up. As I taste my palate slowly realigns itself to take into account the astringency. The enormous glass balloons now make perfect sense. The wines need time and air. Discussion of wine does not revolve around critical analysis of the wines themselves but the ethos of farming, the desire (or otherwise) for consistency, the importance of being true to nature and the role of the vigneron as a patient observer. Indeed all conversations with the growers return to nature with a capital N, as the wines are viewed as part of a grander scheme rather than a consistent commercial product. “It does one good to patiently observe what happens in the peace and tranquillity of nature. And the best occurrences are those that take place without influence from outside sources.” I willingly admit I have such high respect for developments happening unseen- both in the vineyard and later in the wine itself- that I´m afraid of disturbing and defacing the natural process through interference… (Franz Strohmeier following C.G. Jung) This is a studiously humble approach as it posits understanding and listening instead of manipulation and adjustment. Franz continues this theme: “…with these thoughts, we want to encourage you, to become more sensible and alert. Make us aware, what is good for us and our environment. Our living today is in most things technical, what is quite useful. But life is also playful: Love, simplicity, silence, flowers, dancing or painting and art – these things include our inner world. We are equally as passionate about taking time to savour our wines, to enjoy the perfect symphony of liveliness, salubriousness and sustainability.” This is an invitation to experience beauty, the vines and the wine being the conduit to such experience. We understand here the philosophical dimension of biodynamics, that nature is the universal teacher to be listened to and respected.

The Whole Picture What gives these wines their exceptional longevity? The structure comes from the grape matter and the grape matter derives from the essence of the vineyard. Viticulture is sensitive and dedicated to promoting healthy soil structure. Franz allows the soil to retain its natural plants and fauna and only mows one or two times. Every second row in the vineyard is cut to allow enough space for an uninterrupted blossoming natural environment for indigenous insects and animals. Under the vines themselves the grass is cut simply with a scythe. The use of tractors is minimised to ensure that the soil is not compacted. All forms of life are encouraged from the smallest cell to highly developed plants and animals. This explains the aspect of “love” of all species in these “symbiotic vineyards”, one reflected in the name of the range that they give their natural wines: “Trauben, Liebe und Zeit” (Grapes, Love and Time). Nurturing is done with nature in mind; the Strohmeiers harvest and produce plants and blossom extracts for teas including extracts from nettles, yarrow and chamomile and valerian and hawkbit tinctures. Various biodynamic preparations are used such as 500 & 501, and although small amounts of copper and sulphur are used (with such humidity mildew and rot are inevitable) they try to minimise total treatments to 0.3- 2kg of copper per year, In 2011 Franz replaced sulphur sprays with whey as supposedly the lactoferrin in whey and milk causes the hyphae of the Unicinula necator to collapse within 24 hours, a useful natural alternative. Harvest is extremely selective with bunches cleaned up in the vineyard. Yields are naturally very low. The destemming of the grapes is followed by spontaneous fermentation. The grape must sees no additions or other interventions in order to allow the grapes to be transformed into wine as purely as possible. Chardonnay, Weissburgunder and Schilcher wines are pressed without maceration. Sauvignon Blanc here – as well as the red wines – are fermented and pressed on the skins. With the exception of Schilcher, all wines are kept in wooden barrels; red wines are aged in 225 litre barrels, the remainder in 500 litre formats. Maturation in can take up to four years. Time and love. Love and time. The next morning is brilliantly sunny and warm and we drive ten minutes to see one of Franz’s other vineyards in Stainz. A mixture of rain, rot, oidium and mildew have poleaxed the grapes. Despite this obvious damage Franz shrugs his shoulders – nature gives, nature takes away. One of the vineyards runs riotously, its shaggy furrows bisecting some crazily lopsided vines. Once more he takes out a spade, lifts the grass and gives us the soil to hold and rub over our fingers. This is important, looking and smelling – it is fresh, sweet and vital as if to indicate that the vine is breathing good things.

Pingback: A Styrian Adventure: Part 2