Read Part 1 HERE

Dragonflies, Stag Beetles, Salamanders and Butterflies

Franz leads us to a layby where Andreas Tscheppe is waiting. Andreas apologises profusely for his lack of English (they all speak excellent English, of course) and takes us to a vineyard on one side of the valley. We learn later this is the Green Dragonfly vineyard – all Andreas’ cuvées are named after an insect or creature that dwells in the habitat surrounding the vines. Despite the heat of the day and the sun beating down overhead this seems to be a cooler location exposed to a touch of breeze and well ventilated vines. The views are stunning – hills and mountains roll into the distance and clumps of forest cling to the slopes surrounding the vines. Despite (or maybe because of) the depredations of rot, oidium and the grape-munching insects, the vineyard is rocking with vitality. Andreas is smiling – he is in his element. He is touching the grapes, popping them into his mouth, plucking a leaf or two off the sparse canopy. The grapes taste good, especially the Chardonnay, but the late-ripening Sauvignon needs more time.

Having munched through around half the potential harvest (them’s good grapes) we take a wee detour through Slovenia (right on the border here) and then across to the other side of the valley where Andreas’ other terraced vineyards are located. The vines here are very spacey and even include a few rows of Pinot Noir which we will taste later. He says he will replant these because they are the wrong clones.

Before lunch we taste on the terrace with the sun beating at our backs. The harvesters are out picking the vineyard immediately behind us (which belongs to his brother). Andreas will be out in the next day or so if the weather holds (as it transpires it doesn’t!). His labels have animals on them – the stag beetle is the motif of the winery. The two Sauvignons are characterised by a blue and a green dragonfly, denoting which vineyard they come from. Both are delicious, but the green dragonfly has a bristling minerality that wakes you up. All the wines are excellent, bright and crunchy.

We go to the cellar (which he and Ewald, his brother, share). Here we taste a Sauvignon/Chardonnay blend (Stag Beetle) from a cask that is buried in the earth wherein the wine ferments, some fabulous Muskateller two ways, and other bits and pieces including the aforementioned Pinot Noir.

Each person brings their personality to their wines. Andreas’ wines are chirpy, bouncy and bright, maybe not as intense as those of Franz Strohmeier or Sepp Muster. Nevertheless, they have a brilliant energy, the Muskatellers are joyous and original, whilst the Stag Beetle and Green Dragonfly wines positively crackle with life.

Sepp Muster

When we arrive at Sepp and Maria Muster’s beautiful house next morning the weather has completely changed and the temperature has plummeted by about 12 degrees. Most of the vignerons had intended to harvest today but bitter & damp winds have put paid to those plans. As we stroll along the road bisecting his vineyards Sepp points out the local topography. The landscape is very undulating with vines peeling off steeply in all directions from the top of the slopes. Copses, dotted at the bottom of the slopes, create myriad micro-climates for the vines that seem to be at the confluence of several weather systems.

The vineyards themselves, at a typical altitude of 450-470 m, are notably rocky with clay and silt soils dominating their steep, hand-worked slopes. The character of the wines stems from this unique location, situated in this “illyric” microclimate with the influence of the Koralpe (the nearby high mountain plateau region), with its cool nights and winds being mainly responsible for the character of the wines.

The vines grow on lime soil, composed of solid clay silt, known here as “Opok” which results in warm “dense” wines with intense varietal aroma character. The vines look wild and primitive with their single wire trellising, a reflection of the original method of vine training developed by Sepp’s ancestors’ they rise high along chestnut wood posts and branch out at approximately 1.80 metres height. The one-year canes hang down from the wire as if bending towards the earth. This practice was developed to promote a harvest of physiologically-ripe grapes, the idea being that the energy of the vines goes not into creating a canopy of leaves but into the very subtance of the grapes themselves.

Sepp echoes the simple mantra that we have heard so far that he does not wish to fashion his wines to any specific style, but rather allow them time and space to reach their own individual potential, referenced through terroir, soil character and vintage. It’s the classic hands-on, hands-off approach, emphasising awareness of tradition and the need for observation, seeking healthy vines to yield healthy grapes, and then allowing the wine to make itself in the cellar with the minimum of fuss. As he says with a smile when we enter the barrel room: “I don’t come in here very often.”

The chief preoccupation, as with Franz, Andreas & Ewald, is to build soil and vine vitality by using biodynamic practices. For Sepp this involves the dynamising and spreading of plant, mineral and animal substances and working according the Maria Thun calendar. Cluster thinning is partly naturally generated, partly done by hand, the goal to produce small berries, highly aromatic grape material as the basis for full character and complex wines.

The wines represent the overall character of their immediate surroundings. This involves the singularity of the vines, soil, microclimate, people and vineyard location as well as the specific vintage and results in individual, fine and multiple-layered (complex) wines, which over the years, alter in their aromatic structure.

The cellaring process is where nature meets time. Spontaneous fermentation (with natural wild yeasts) in large format barrels, no temperature control, naturally occurring malolactic fermentation, nothing added, nothing taken away. The wine is aged (up to two years) to obtain the optimal maturity and harmony of the various flavours.

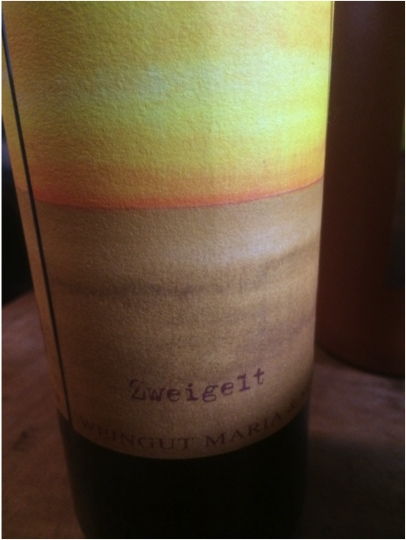

Sepp makes wines in different styles, but they share the same natural spirit. Vom Opok wines are from hand-harvested grapes grown on clay/silt soils towards the bottom of the steep slopes. The wines themselves are fruity with soft mineral character and lively acidic fruit. Sauvignon, Morillon, Welschriesling, Zweigelt, Gelbermuskateller, a white and a red blend and even a Schilcher provide a fantastic and fairly priced introduction to the wines from this region.

“Sgaminegg & Graf”

The Graf wines are from carefully selected handpicked grapes from south-facing slopes with specific soils (i.e. “Opok”) and naturally small grape cluster. These wines differ from those of Vom Opok vineyards having a fuller structure, more extract/density and pronounced mineral character. The influence of the Koralpe doesn´t play as much an influence in the grape aroma in that they are more protected from it than the Sgaminegg vineyard. These wines are bottled after 22 months in the cellar.

Sgaminegg comes from the best vineyard of the estate with pure Opok soil, the sparsely-foliaged vines yielding tiny grape clusters (15-20 hl/ha). The winds from the Koralpe play their influence here directly. Sauvignon and Morillon are matured in wooden barrels, blended and bottled after 22 months. The wine has a cool, austere feel as if the very limestone rocks had fermented slowly with the grape juice and released their stony essence into the wine.

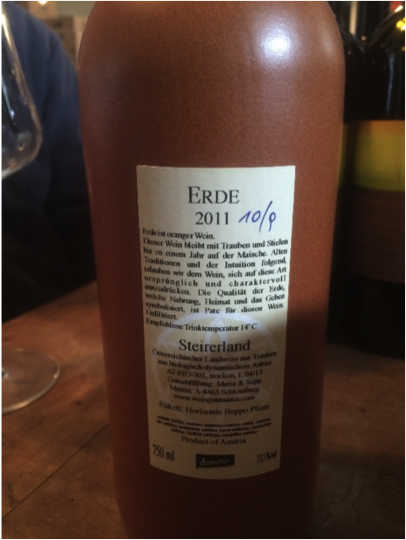

Finally, Sepp makes two orange wines where the juice is fermented with the skins – and partly with the stems. These skins and stems contain colour pigments, tannins and phenols, which impart the “orange” colour. This can vary according to variety and year from a rich yellow, also pink, to a vibrant orange. The texture is concise, compact, rich in tannin, aromatic and complex.

Only the smallest tightest-skinned berries are harvested. The “Gräfin” (Sauvignon Blanc) ferments 2-4 weeks on skins, whereas, “Erde” (Sauvignon Blanc, Morillon) remains between 6-12 months with skin contact. The wines are, of course, spontaneously fermented. They are not sulphured and mature in wooden barrels for at least 20 to 24 month and bottled without filtration or fining. The Grafin is more floral and fruity, the Countess with a feminine mien, where the Erde is more intense, spicy and earthy – again, befitting its name. The wine is housed in rather quirky clay bottles – a homage to Georgia, perhaps, where the wine returns to its clay roots.

This part of Styria and in particular the small group of growers who belong to Schmeck das Leben seems like a remote village in the world of wine. There is a wine culture, but it is humble to point of being self-effacing. The growers are not heroes in their own region and their practices are considered unorthodox and even damaging. They are not crazed ideologues – though certified by Demeter, Austria, they have little interest in the cachet or the paperwork. They work in the way because it is right for the environment, right for the wine, right for them. There is no commercial imperative.

They all believe that wine is one element in the whole. You often hear the word happiness and personal fulfilment when you are talking to these guys. This is the human component of biodynamics based around the notion that one is healed by one’s interactions with nature and the land. Yes, Nature does have a capital N.

Biodynamics means biodiversity and trying not to damage natural organisms from the birds to the bees to the tiniest cell life. A functioning vineyard must live on every level. The vignerons pay particular regard to the soils and avoid using tractors or cutting the grass aggressively, minimise copper and sulphur treatments to the bare minimum and use teas and biodynamic sprays to activate and salve.

The vines are straggly. Bunches are uneven, grapes will rot and be discarded. The training systems are peculiar to the vineyard, the region and the grower – more concerned that the energy of the vine goes into the flavour of the grapes.

Terroir is important, expressed through intensity of flavour rather than primary aromatics. The solidity of the wines is built on pillars of texture and tannin rather than acid and alcohol. The ageing in wood relaxes the juice but confers a certain architecture. The wines aren’t noticeably woody, but they have a wood influence, in the way that any ageing vessel will help to shape the final wine. The tannins seem to emanate from the grape juice itself. Sauvignon is the glory of the region and the grown-up way that it is handled yields a mixture of spiciness and mouth-weight. Many of the wines had distinctive herbal inflections (wild mint). The key here is to thin out the leaves during the ripening period, harvest late, allow malolactic and long ageing in barrels.

The final piece in the puzzle is that they have all relinquished sulphur as a preservative. Here, to coin a phrase, one can literally taste the difference. Each of the vignerons show us examples of wines made with minimal additions – they are good, sturdy, irreproachable wines. We then taste the same wines (although from different vintages) without sulphur. The wines taste liberated and expressive as if the merest dose of SO2 had throttled back on the fruit and terroir. Wine is a subtle, living organism – such a simple comparative exercise illustrates how it breathes, how it behaves. We always sampled in massive Burgundy balloons; on several occasions we were allowed to try wines that had been opened 2, 3, 4 weeks and even longer. You notice that the oxidation is barely perceptible, the colour has not changed, the freshness is enhanced rather than dulled. It goes against the grain of wine knowledge, but so much of we have seen and tasted speaks volumes in its own idiom. As the growers might say it is instructive to accompany the wine on its journey and “to take time to make one’s soul happy”.

This perspective is refreshing as it gives a deeper meaning to being a vintner. Growing wine is (I like that expression) about helping to be part of a process that gives rise to unique sensations and feelings (both in the grower and the drinker). It is not about creating a product directed towards an audience of critics and consumers. It is accepting what nature bequeaths, it is about respectfulness, sensitivity, integrity and generosity. This is more than a political pocket of natural resistance or polemical approach to biodynamic, it is group of people farming in the right spirit, doing what makes them happy, the result of which turns out some pretty stunning wines!

Pingback: Orange weekly: Andreas Tscheppe – Hirschkäfer Erdfass 2006 | The Morning Claret