Read Part One HERE.

[The three musketeers and D’Artagnan are escaping from the Cardinal’s men in his own coach]

Porthos: Champagne?

Athos: We’re in the middle of a chase, Porthos.

Porthos: You’re right – something red.

–The Three Musketeers (1993)

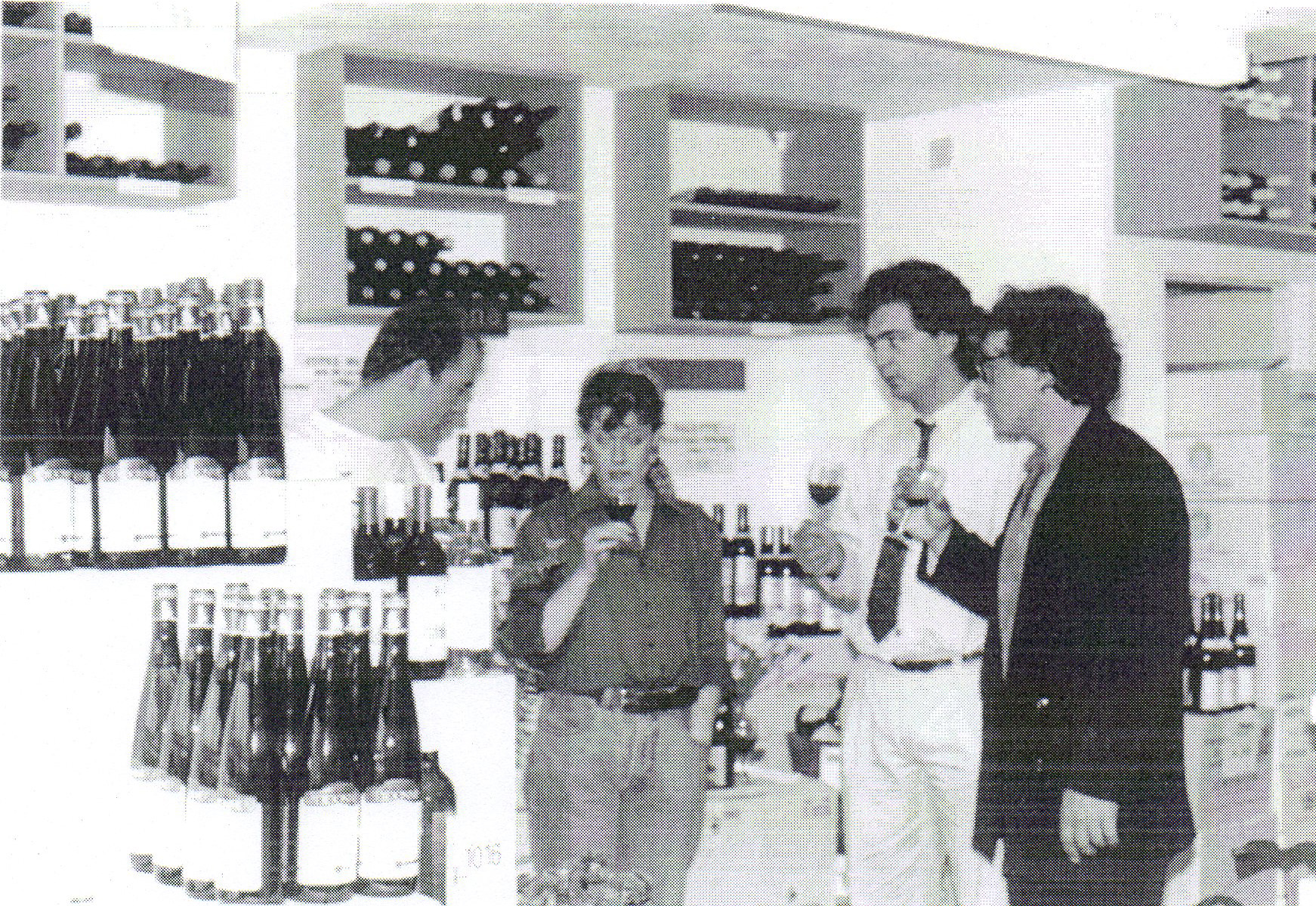

I am in a large hall in a place called the Duke of York Barracks just off the King’s Road. There are a couple of dozen Gascon growers milling around and more than a few massive brick-shithouse French rugby players sporting standard cauliflower ears and conks like puffball mushrooms. The air of utter nutter chaos is pervasive. This was our epochal tasting for Les Vingt du Sud-Ouest, featuring the rising stars of this comparatively unheralded wine region.

We were intimately, yet also loosely involved with the organisation of this event, most of which seemed to take place on the day itself. It was a classic example of early-days Les Caves semi-organisation, the force of sheer will combining with beautiful naivety, to transcend the muddle, and triumph in the end.

The air of utter nutter chaos is pervasive.

The only thing I remember clearly from the day was the sheer bewilderment of a famous wine journalist trying to navigate the wines on the tables without the cicerone of a tasting sheet. The words “in charge who the f is” are indelibly printed on my brain in some random order.

After the shindig, there was a colossal banquet conjured in the most rudimentary field kitchen imaginable, cooked up by five famous regional SW chefs; plenty of incoherent Franglais speechifying, and the extravagant belting out of a whole lot of rugby/folk songs. The French are genetically programmed to sing at the end of the evening’s entertainment, and every son and daughter of the soil carries a tune in their bucket. Which makes the French like the Welsh. Or the Irish for that matter. This spontaneously-fermented event set the standard for future Les Caves de Pyrène gastronomic extravaganzas. Like a huge lock forward tackling a tiny fly-half, we would enfold our guests with our bearhug hospitality, and leave them to happily count their bruises and hangovers.

It was a classic example of early-days Les Caves semi-organisation, the force of sheer will combining with beautiful naivety, to transcend the muddle, and triumph in the end.

This was the first real sense I had of our Gascon origins. If terroir was the lines in a vine grower’s face, then here was terroir etched in spades. If terroir was making the wines sing and dance, then there was singing a-plenty, if not dancing. If terroir was the expression of the spirit of the region by cooking food using local ingredients, then this was the cuisine de terroir. By its craggy features and sonorous marc-marked voices and lashings of foie shall ye know terroir.

Cyrano:

- How about that nose?

- What a nose!

- It’s a nose that blows you away!

- You can pick that nose anywhere!

- If that nose was any greater it would eclipse the sun.

- Enough with the Cyrano schtick. The nose may be bulbous, but the palate’s fucked.

Sheer e-Frontonary

One of my earliest selling gambits was to try to instil customer confidence in a wine by making wildly picturesque assertions such as: “This is the wine they are drinking in the bars of Toulouse”. I had no idea, of course, if there were any notable wine bars in Toulouse let alone whether the wine we were assaying was present and correct and being quaffed there, but already I was developing a kind of rudimentary hipster-chic approach by means of latching fervidly onto trends. Or just inventing the trends. Carcassonne, Collioure, Pau, Nantes were also endowed with unfeasibly lively wine bar scenes in order to illustrate the demotic appeal of the wines I was trying to offload. Even if they had no wine bars. But if there were wine bars in Toulouse then the Frontons of our genial friend, Marc Penavayre, would be guzzled with alacrity there.

Fronton might be described as an “honest guv” wine.

To me

He is all fault who hath no fault at all:

For who loves me must have a touch of earth

–Tennyson, The Idylls of The King

A little historical context. Fronton and Villaudric are embraced in the Côtes du Frontonnais. We are due north of Toulouse here, where the funky wine bars live, and just west of Gaillac between the Tarn and the Garonne. The unique Négrette grape grows here. We love a grape with a back story. The story goes that the Knights Templar brought the vines back from Cyprus almost nine hundred years ago and called it Négrette because of its dark skin. Fronton itself is one of the oldest vineyards in France, the Romans having planted the first vines on the terraces overlooking the Tarn Valley, but it was only in the 12th century that the Négrette appeared, the variety which was to write Fronton’s history. Such as it was.

At this time, the vines in question belonged to the Knights of the Order of St John of Jerusalem. They were the ones who, on one of their crusades, discovered and brought back a local grape from Cyprus, the Mavro (which means black in Greek), out of which the Cypriots used to make a wine to “increase their valour.” The Knights introduced this grape to their commanderies in the Occident, including that of Fronton. Over the years, the Mavro became the Négrette and is the origin of the typicity of Fronton wines, the only area in France where this variety has become perfectly and durably acclimatised. There are a few vines in the Loire, for grape sleuths out there.

When Calisstus II, 160th Pope after St Peter, came to consecrate the church in Fronton on 19th July 1191, he was so enthusiastic about the wine that he demanded that its praises be sung on parchment. It was not recorded whether this was a dirty ditty or the first recorded holy rugby song.

The French are genetically programmed to sing at the end of the evening’s entertainment, and every son and daughter of the soil carries a tune in their bucket…This spontaneously-fermented event set the standard for future Les Caves de Pyrène gastronomic extravaganzas.

Much later, the two neighbouring parishes of Fronton and Villaudric quarrelled over the supremacy of their soils. The story goes that in 1621, during the siege of Montauban, Louis XIII and Richelieu, having each taken quarters in one of the two towns, sent each other a gift of the respective wines.

As well as being an excellent historical chess piece Négrette makes good quick-maturing wines, quite low in acidity, but with a pronounced and particular flavour of almonds, white pepper, cherries, rhubarb and liquorice. The wines may be given heft by the addition of Syrah, the Cabernets and Gamay in various quantities. The less “confidential” ones do tend to reflect their terroir: the soil is poor here, red stone called rouget with a base of iron and quartz and it seems to migrate into the wines as a mineral component with an agreeable digestibility.

Based in the village of Vacquiers in the south-eastern part of the appellation, jovial Marc Penavayre of Chateau Plaisance makes wines that are a sheer joy to drink. The vines are planted on the highest terrace of the Tarn at an altitude of about 220m. The baby cuvees are aromatically akin to putting your nose in a cherry clafoutis and his more structured and age-worthy wines have a pleasant sanguine quality that makes them equally drinkable. It’s the warmth of the man that seems to communicate itself in the smiley and smile-inducing wines.

Marc makes a particularly delicious no-sulphur cuvee called Serr da Beg. In Breton this is “On se tait et on déguste”…which is “let’s just shut up and taste!” By taste, I think we mean drink. His idea of wine is straightforward, that it should “speak the earth.” Even though our other south west friends are now also making no-sulphur cuvées – and delicious wines at that – they are not really recognised for their efforts by the natural wine fraternity. One domaine that has bucked that lack of trend is Domaine Plageoles in Gaillac. Which goes to show that a fun label goes a long way in the world of vin nature.

Plageoles and Gaillac Rad Trad

Tradition is not a return to an obsolete past, but rather the permanence of its origins through time. –Frederik Tristan

Gaillac is one of the most original wine growing areas in France in every sense. The Romans started planting vines as far back as the 1st century AD, then in the Middle Ages the Church leased out land to farmers who were prepared to plant vines. François I of France used to buy Gaillac wines. When he visited the town in 1533, he was given fifty barrels as a gift. He offered some of them to Henry VIII of England on the occasion of their meeting in the field of gold and the latter was to drink more of these wines regularly in the course of the following years, as is shown in his accounts books. In the 18th century, Catel wrote the following words in his Memoirs (1633): “Gaillac is a town standing on the Tarn river in the region of Albi; this terroir is widely renowned for the excellence of the wines that are grown there, which are sold to both Italy and England…” and he added that “the wine is perfect for the stomach and is not in any way harmful, for it goes to the veins rather than to the head”. The range of grapes and styles is amazing, the limestone slopes being used to grow the white grape varieties, whilst gravel areas are reserved for the red grapes. The Mauzac grape, for example, is especially versatile: it is resistant to rot and ripens late and may be found in everything from sparkling wines (methode rurale or gaillacoise was being praised by Provençale poet Auger Gaillard long before champagne was a twinkle in Dom Pérignon’s eye) through dry (en vert), to semi sweet and even vin jaune. Mauzac is gently perfumed with a nose of apples and pears and an underlying chalkiness. The other major variety is Len de l’El, which, in Occitan, means “far from the eye” (loin de l’oeil). The reds are made predominantly from two more native varieties, Duras and Braucol, although the temptation to create a Bordeaux style in the interests of commercialism has meant that grapes such as Merlot, Cabernet and Syrah have found their ways into blends. Robert Plageoles has been dubbed “one of the artists of the appellation”. Mauzac is his particular passion. He produces all styles; the accent is always on wines with purity, delicacy and finesse.

Barthes said that current opinion (which he called Doxa) was like Medusa. If you acknowledged it you become petrified. We feel he would have approved of Robert Plageoles.

Robert and Bernard Plageoles believed in rediscovering what has been lost and may be said to be grape archivists. Not for them the slavish adherence to global varietals; they grubbed up plantings of Sauvignon and concentrated instead on the native Mauzac, in which they found the potential for a whole range of styles. (There are various versions of Mauzac – vert, en jaune, roux, noir…). Mauzac, when dry (or sec tendre to be precise) can produce a fascinating soft style redolent of pears, white cherries and angelica; it is also responsible for sparkling wines and an array of sweeties ranging from the off dry to the unique piercingly dry sherry-like Vin de Voile. This latter arcane wine is made from the first pressing, which is fermented in old oak and returned to the same barrel where it remains for a further seven years, losing about 20% of volume. After a year the must develops a thin veil (voile) of mould which protects it from the air. The flavour is delicate, reminiscent of salt-dry amontillado, with the acidity to age half a century. This curious wine would go well with a soup of haricots beans laced with truffle oil or a Roquefort salad with wet walnuts. The Vin d’Autan, on the other hand, is made from the revived obscure Ondenc (“the grape which gave Gaillac its past glories”) in vintages when the grapes shrivel and raisin in the warm autumn winds. According to Paul Strang, Robert Plageoles describes it as “a nul autre comparable, il est le vin du vent et de l’esprit.” They order these things better in France (I wish I’d said that too)!

Robert Plageoles has been dubbed “one of the artists of the appellation”.

The younger Plageoles generation have taken up the cudgels and are producing bonny, bright and effortlessly natural-tasting wines. Bro-Cool is the new Braucol (geddit?) with the sort of label that Instagram was invented for. We’re back in Marcillac taste territory – bright, savoury nose, notes of gravel, earth, and spice. Ladle on cranberries and red cherries. Delightful sapidity. Light alcohol and crunchable tannins. The unusual Mauzac Noir is made the same way – this pale red very individual wine has earthy, vegetal aromas, notes of green and white pepper and a touch of cherry and blueberry on the finish. The Prunelart (a grape revived by the Plageoles and vinified as a varietal) is darker and a more powerful grape. Rich, lifted, plummy nose leading to a silky-smooth palate, with plum, soft liquorice and something cool and fresh too – green peppercorns, and then meat and earth come into subtle play with the bright fruit. Some gentle, fine, peppery, spicy tannins kick in, keeping the finish fresh. Prunelart is the art of pruniness – onomatopoeia works! They also make a tiny-production wild natural wine where a crazy collection of rare native varieties is field-blended to prickly-earthy effect. Called Terroiriste, it is sold in our wine bars, and is an ebullient fist-punching statement of soifability, clocking up plenty of Insta-love whenever it is poured.

With their rustic personality the wines of Fronton and Gaillac are refreshingly unpretentious. They haven’t been discovered and are presumably being drunk in those wonderful and perhaps mythical wine bars.

The Big Three: Cahors, Madiran, Jurançon (with Irouléguy in despatches)

Hallowed be thy Cot: Cahors is a bit of a conundrum. It has a long and complex wine history. Vines were originally introduced by the Romans, and when the river Lot was eventually adapted as a trading waterway, the reputation of Cahors became established all over the world. By the 14th century Cahors was being exported throughout Europe including England (where it earned the sobriquet of “The Black Cahors!”) and Russia; it was even considered superior to Bordeaux in France. Paul Strang quotes Monsieur Jullien in his book Wines of South-West France describing this strange black wine: “They make a point of baking a proportion of the grapes in the oven, or bringing to the boil the whole of the vintage before it is put into barrel for its natural fermentation…The first-mentioned process removes from the must quite a lot of the water content of the wines, and encourages a more active fermentation in which the colouring agents dissolve perfectly”. Tastes change…now one can find wines made by carbonic maceration, and several producers work with micro-oxygenation, a technique pioneered by Patrick Ducournau in Madiran, to create fleshy dark red wines, whilst Jean-Luc Baldes has created his version of the original black wine. By the way, an anagram of Cahors Auxerrois is “Ou! Six Rare Cahors!” Sometimes, as Voltaire said, the superfluous is very necessary.

Cahors was also one of the areas devastated by phylloxera and a massive frost in 1956 which destroyed most of the vines. To get an idea of what traditional Cahors might have tasted like one can try the wines of the Jouffreau family (Clos de Gamot and their other project Clos Jean).

Malbec (Cot, Auxerrois) can remind us of dried flowers, tea and fresh herbs – almost Nebbiolo-like, when it is allowed to express its subtle personality. It has, however, mostly gone the way of modern Bordeaux with long maceration, pump-overs and lengthy ageing in small barrels and over the last two decades has felt the heavy shadow of Argentinian blockbuster Malbec, so much so, that the apprentice has begun to teach the master (bad habits!) as it were.

Digression: The Resistible Rise of Arturo Oenologist

Wine, after all, is big business, and business demands global models and standards regarding the qualitative homogenisation of the product. At the one end of the market spectrum this manifests itself as the ongoing corporate battle for wealth, for influence, for prestige, for land. To acquire influence, one must play the game: wine is thus made (tweaked, amplified) to conform to a perceived notion of excellence, tracking the palates of influential journalists. The product thus becomes a means to an end: firstly, a desire for critical approval, to be the smartest clone in the class; secondly, to perpetuate the notion that anything can be achieved by facsimile winemaking procedures. In short: meet the Stepford wines.

When we know that the country of origin is wholly irrelevant: that virtually identical wine can be produced in Pomerol, California, Italy, Spain or Chile by a flying winemaker, this is tantamount to a colonisation of taste, of a kind of vinicultural imperialism that gives us an endless succession of smooth, sweet, varnished wines – everything that the palate desires except individuality, except identity, except angularity. These may be big wines in scope but they are small in spirit – as Promethean as a cash register as Pauline Kael memorably said of one epic film. Whereas some architecture springs from the spirit of the place and is an extension of the landscape and other architecture is an imposed collection of foreign materials; whereas some vineyards reflect the biodiversity of the area and other vineyards are a monoculture of the vine, so wines can either embody their locale – from the flavour of the terroir to the aspirations of the grower – or they can be entirely incidental to place. If the latter is the case, don’t look for the address on the bottle; look for the name of the winemaker.

Oak + extraction = indigestion

So, I said to my friend Carlo: “Let’s drink something dangerous”. In retrospect I’m not sure what I meant by that. Partly I meant “Let’s spend more money than we would normally do on a bottle of wine and risk being disappointed, but the sneaking, faux-natural, quasi-spiritual part of me wanted to sample an extreme wine that would trip the light fandango and send tiny squalls of reverberating flavours to the outer limits of my palate. Or something.

I order a rich Cahors wine. The meta-cuvée, so to speak. More is more, right?

Wrong.

At first the upfront fruit fronts up, but after a couple of snifters I feel like Woody Woodpecker rattling my beak against a solid oak tree. As the wine opened up it closed down, as if knackered by extreme lacquer, the classic old Duke of York style: It marched all the fruit up the hill, then it marched it down. A classic example of underwined oak.

And the wood tannins grow and grow and my tongue becomes enveloped in leather. That oak – not so much a structural corset as a dense overlay of toasty sweetness bruléed by an overenthusiastic blowtorch. I mentally contrasted this with a ridiculously drinkable, unassumingly rustic Marcillac from jester-grower Jean-Luc Matha that I had consumed the previous night, single-handedly. It had slithery red fruits, was tinged with graphite and edged with iron and blood and condensed the sentiment “I sneer at your oak and I generally thumb my bulbous nose at your extraordinary pretensions” into the concise command “Drink me!”

After a couple of snifters I feel like Woody Woodpecker rattling my beak against a solid oak tree.

My attitude towards abusive oak regimes hardened further after a recent tasting of about thirty Cahors. Not my preferred summer pursuit but someone had to do it. Most growers, one might fondly imagine, would want to express the particularity of terroir in their wines and thus seek balance and vivacity. The flip side is the vigneron who develops a selection or top cuvée – normally made from the ripest fruit in the best vineyard – wherein the juice must further needs be coddled and cajoled to reach the pinnacle of opulence. The intention does not always beget the desired result in terms of quality. Whilst it is a perfectly legitimate aspiration to have, say, a single vineyard expression of a wine, or to highlight the character of a grape variety in relation to the terroir in which it flourishes, delivering excellence is not the automatic by-product of creating something intensely powerful and bombastic. Wine should, like the intelligent person, be capable of subtle discourse rather than screaming extroversion.

The first Cahors in the line-up was a simple wine wafting hints of sweet berries and earthy freshness. My kinda Malbec. One could imagine drinking it. Thereafter, downhill with a relentless succession of termite’s toothaches, reds hoist on their own very wooden petards, as if the oak had exploded the very soul of the wine itself. Eventually, the entire tasting became a diminishing return as my palate was gradually embalmed in a thick fug of disassociated sensations.

Harsh criticism? Not at all. I don’t actively seek faults and wish to derogate wines. In this case I love the region, but I wonder whether too many growers are now taking themselves too seriously, making wines to impress people rather than to give them pleasure. The danger, of course, is that in trying to make the wines more serious, you unmake them and allow their very spirit to unravel.

Are we to drink oak juice? Is the wine to be reverently scooped (or carved) out of the bottle with a sharp spoon? Will it digest our food or clog our arteries? Is it meant to drunk at all or placed rather on a high altar in the heaviest bottle imaginable for us to admire as the Platonic idea of a luxury wine?

Oak is not a bad thing per se; it is a kind of seasoning for wine, but should always be used sensitively. I recall tasting a wine in Spain a few years ago from tank that had beautiful, lifted purple fruit. If only it was left alone and bottled, but the winemaker felt the need to age the juice in eight different types of oak barrel for eighteen months. Everything was diminished, the colour dulled, the aromas and fruit befuddled, a humdrum sow’s ear made out of a silk purse. In this case, as in so many others, less would have been infinitely more.

Mal-adroit – Primus Malbecius Superbius

Sometimes you taste a wine so rich that you are tempted to tap it on the shoulder and ask it for an unsecured loan of $100,000,000 Zimbabwean dollars. Reading an estimable wine organ recently I discovered that there are wines among us that do not merely court perfection, they seek to transcend it. As a mere humble vessel with a shallow palate accustomed to coarse French wines I needed to understand that greatness can only be critically arbitrated by those whose mouths that can carry a greater weight of wine in them…

Primus Malbecius Superbius emanates from irony-free vines grown at 3000m high in the Andes whose deep-delved roots are verily refreshed by the purest glacial melt waters known to man. Cuttings for the vines were sourced from Malbecistan, a tiny lost republic nestling in the Caucasus Mountains and the undoubted cradle of wine civilisation as we know it. So saturated with ripeness that the bunches touch the soil, the grapes are individually plucked by trained condors who carry their precious burden back to the winery, a glass and metal cathedral construction laid out on the lines of an ancient Incan temple. Each barrel in the cuverie is fashioned from 200% new oak, toasted evenly on both sides by artisan coopers flown over by private jet from their villages in France and after a 60-day maceration to ensure that no light can escape the wine and pigeage with velvet-coated battering rams, the wine matures to the mellifluous sound of Bolivian pan-pipes and massed devotional choirs. The first cask samples are tasted by the cowled and hooded Parkeristas, a cabal of gauchos, who repeatedly murmur binary incantations of ones and two zeros until the wine is imbued with incontrovertible supranumeral greatness. It is then given the sacred papal benediction of Rolland who releases nano-bubbles of reputation into the wine until it is so smooth that it begins to drink itself.

THE VIRTUES OF SIMPLICITY: A digression thereon

When first my lines of heav’nly joyes made mention

Such was their lustre, they did so excel,

That I sought out quaint words, and trim invention;

My thoughts began to burnish, sprout and swell,

Curling with metaphors a plain intention,

Decking the sense, as if it were to sell.

Thousands of notions in my brain did runne,

Off’ring their service, if I were not sped:

I often blotted what I had begunne;

This was not quick enough, and that was dead

Nothing could seem too rich to clothe the sunne,

Much less those joyes which trample on his head.

As flames do work and winde, when they ascend,

So did I weave myself into the sense.

But while I bustled, I might heare a friend

Whisper, How wide is all this pretence!

There is in love a sweetnesse readie penn’ed

Copie out only that, and save expense.

–George Herbert, Jordan (II)

Herbert, writing about the act of glorifying the son of God, makes the point that the very grandiloquent language designed to exalt and celebrate actually obscures the simple notion of devotional love. In just the same way winemakers may take something which is pure, add lustre and burnish to it and lose the connection with the wine. “Decking the sense, as if it were to sell” describes the impulse to “improve on nature” (plain intention). Style soon supersedes substance: more oak, more extraction, more flavour, and more alcohol, louder, bigger, better – nothing is too good or too much to show the wine in its best light. It is like putting gilded metaphor before meaning or gaudy clothes before the body. Ultimately, the choice is this: is winemaking a natural act, an intuitive and highly sensitive response to what nature provides or is it about the greater glory of being the creator oneself (so did I weave myself into the sense). Our wine manifesto would echo those who argue for “natural wine” or a natural balance: specifically, for no chemicals in the vineyard, neither correction nor amplification of flavour, for a reduction of sulphur, additives and stabilizers and for natural fermentation (i.e. without artificial enzymes). As Herbert writes: “There is in love a sweetness readie penned”. Commercialization has created a competitive wine culture where glossy wines are products created to win medals. There is a fine line between art and artifice in winemaking.

Pascal Verhaeghe of Château du Cèdre has been part of the Les Caves extended family since the beginning. He can do Cahors any which way. The Heritage du Cèdre is the Pugsley in his Addams menagerie. The family traits of abundant dark brooding fruit are evident; the heart is black, but the flesh is youthful. Its lunchtime, and you could murder a Cahors, but you don’t fancy taking out one of the big guns. Heritage is for you, a bonny ruby-red, the Malbec softened by plummy Merlot soothing to the gullet, a nice touch of lip-smacking acidity. It quacks duck magret to me.

Ultimately, the choice is this: is winemaking a natural act, an intuitive and highly sensitive response to what nature provides or is it about the greater glory of being the creator oneself.

Pascal’s Cahors (originally called Prestige) is an inky, spicy red wine endowed with red and black fruits and smoked fig and liquorice flavours. A mixture of new and used oak barrels, the top cuvées are made from low yields and old vines on the estate. The treacle-thick Le Cèdre is “as cypress black as e’er was crow” has cassis aromas and wild raspberry fruit. It is a meal in itself and should be eaten with great reverence and a long spoon. As with his mucker, Luc de Conti, Pascal had a penchant to find the summit beyond the summit, which he did with his Le Grand Cèdre. From vines yielding a mere 15hl/ha, this black beauty, this thoroughbred in a fine stable of Cahorses, is aged in 500-litre new oak demi-muids with long lees contact, and is, as Andrew Jefford once described it so eloquently “strikingly soft, lush and richly fruited, a kind of Pomerol amongst Cahors”.

Having dialled up the volume on his wines for a couple of decades, Pascal then began to tone them down and so began the search for balance, articulated in this mini-philosophical statement.

Nothing is lost, nothing is created, everything is transformed.

–On Nature, Anaxagore de Clazomenes

Like an echo to nature and the never-ending motion of the wine, we constantly evolve ourselves. Our profession is an ongoing creation; much like the philosophers of nature, we experience every day in astonishment, investigation and learning.

Amongst this ongoing movement, our quest is for balance: Ecological balance in the vineyards and preservation of the entire grape quality during wine making. A fragile balance; as every step to transform the grapes is a loss and every action to countervail this loss the beginning of another transformation, we are therefore constantly trying to approach perfection, without ever achieving it. But ever since, this never-ending movement has become a virtuous circle.

Cahors gives us food for thought.

Cahors and Cassoulet: As Nature Intended

Those of you who don’t have duck fat coursing through their veins look away now for this a paean to three C’s: cassoulet, Cahors and cholesterol. Certain foods take me back to places I’ve never been and conjure effortlessly a John-Major style misty-eyed epiphany:

The ploque of boule upon boule in the village sandpit, a glass of chilled pastis, grimy-faced urchins in rakishly-angled caps with their warm crusty baguettes cradled like sheaves, old maids cycling home with their confit de canard – and is there cassoulet still for tea?

Cassoulet is more than a recipe, it is a visceral sacrament based on ritual and intuition. There is even a moral dimension associated with this dish for to cook slowly and with care is to suggest that food is precious, should be savoured and not wasted. Patience is the slow careful flame that transforms the off-cuts, bones, beans and sinewy meat into wholesome nosh, reduces and melds the various components to the quintessential comfort food. The origins of cassoulet and the regional, even familial, variations, recounted so eloquently by Paula Wolfert and others, add to the mystique of the dish, which seems to exist as a metaphor for all such slow-cooked peasant dishes in Europe.

Eating cassoulet without a glass of wine though is like trying to carve your way through the Amazonian jungle with a pair of blunt nail clippers or wading through lava in carpet slippers.

Slow cooking is a luxury in a world driven by convenience and fraught by the notion of wasting time. The genius of slow food is that it nourishes more than our bodies; it also teaches us to appreciate the value of meal time. The taste of things is influenced by the degree to which we engage with food and wine; how we savour and understand it, the value we ascribe to details.

Eating cassoulet without a glass of wine though is like trying to carve your way through the Amazonian jungle with a pair of blunt nail clippers or wading through lava in carpet slippers. We should accept that some combinations are meant to be. It’s called a local marriage not because it is a love-date of perfect unquenchable affinities, but because it is a hearty entente of two mates with close memories of where they come from. Cahors is renowned for its medicinal, iodine flavour; it expresses notes of tea, fennel, dried herbs and figs; it has a pleasant astringency and a lingering acidity. Cassoulet is crusty, oozy and gluey, beans bound by fat. The food requires a wine of certain roughness and ready digestibility. Sweet, jammy oaky reds and powerful spicy wines lack the necessary linear quality; sometimes we should look at wine as an elegant seasoning to the food. Cahors adds a dash of pep (and pepper) to the stew whilst remaining aloof, and cleans your palate by providing a cool rasping respite from the richness of the cassoulet.

To be continued in Part Three.

*

Interested in finding more about the wines mentioned? Contact us directly:

shop@lescaves.co.uk | sales@lescaves.co.uk | 01483 538820