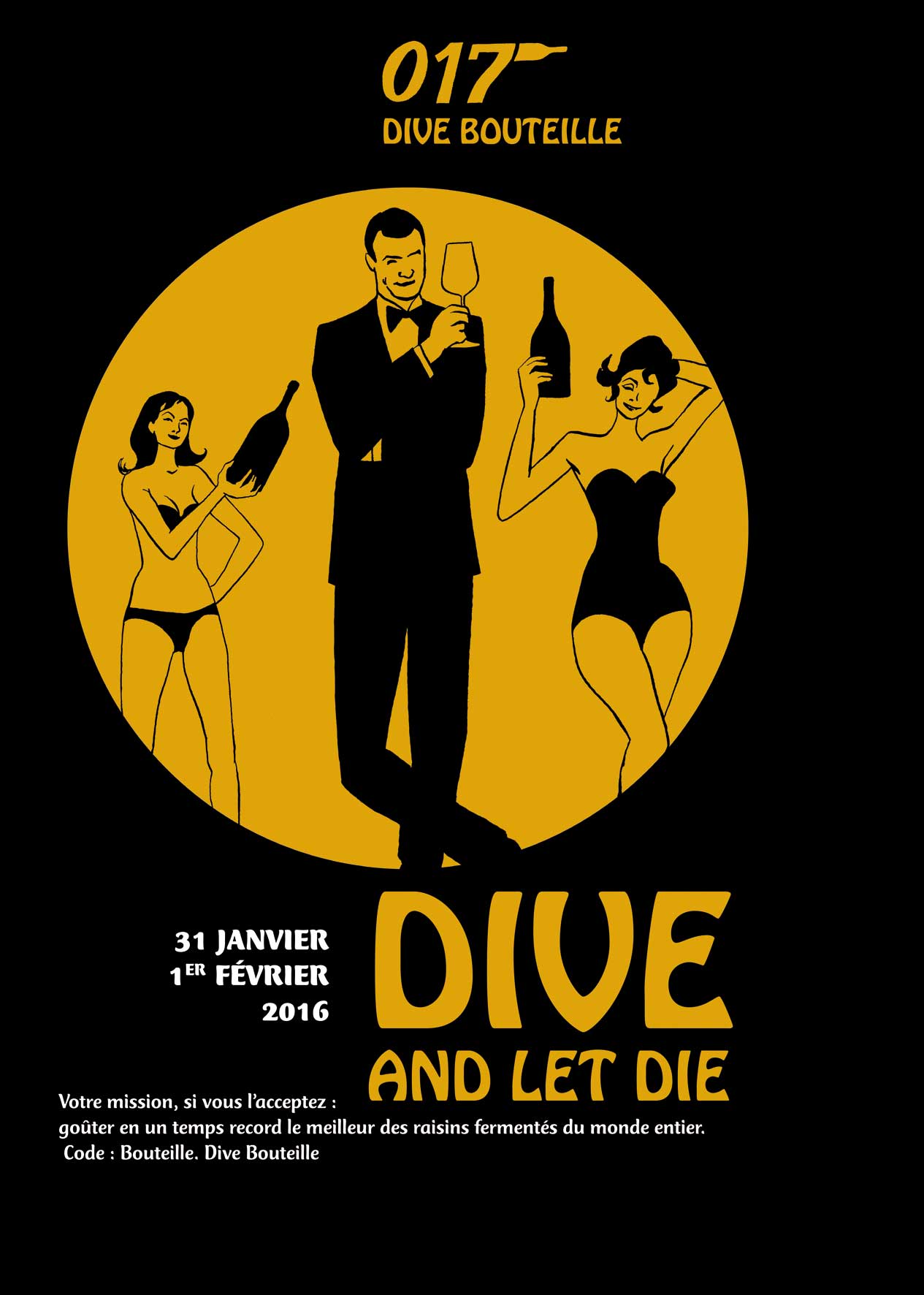

Sylvie Augereau is one of France’s most prolific wine writers and is a passionate spokesperson for natural wine. Sylvie is the founder of La Dive Bouteille, heralded as the world’s largest annual natural wine exhibition, which takes place in the Loire this year from the 31st January-1st February. Sylvie recently took the time to answer some questions about her experiences in the natural wine world. Here they are in both the original French and translated into English (except for when Sylvie herself writes in English!):

How did you become passionate about natural wine?

Drinking bottles and meeting the people behind the bottles!

Who are the growers whose wines (and personalities) have inspired you?

Of course Marcel Lapierre, the pope! He made the scorned region of Beaujolais become the first region that one seeks on a wine list, whether to start the meal, to finish it, or even without eating.

Anselme Selosse [Jacques Selosse]. He makes the longest wines in the world – with bubbles! And [Anselme] is endlessly thinking and reflecting.

Michèle Aubéry [of Domaine Gramenon] embodies the magic of wine. She’s a vigneron who can communicate through the grape; someone who seems to come out from the bottle, like a spirit.

Of course Marcel Lapierre, the pope! Il a fait d’une region méprisée, le Beaujolais, la première que l’on cherche sur une carte des vins, pour commencer le repas, pour le finir, et meme sans manger.

Anselme Selosse. Il fait le vin le plus long du monde avec des bulles! Et sa réflexion est sans fin.

Michèle Aubéry. Elle incarne la magie du vin. Celle que le vigneron transmet au raisin. Celle qui sort parfois d’une bouteille comme un esprit.

For you, what defines a natural wine? Do you feel it is more a philosophy, or an approach to winemaking, or is it something more definite than that?

A natural wine is one made simply from grapes fermented with the yeasts from their terroir. It signifies also that you do not do anything to hinder [the grapes’] expression.

Yes, this approach can become a philosophy. In any case, it is a commitment, a revolutionary act, since [making wine naturally] is a big risk: you can lose a whole year’s work.

Le vin nature est simplement un raisin fermenté avec les levures du terroir. Celà signifie que tu ne mettras rien qui entrave leurs expressions.

Oui, celà peut devenir une philosophie. En tous cas, c’est un engagement, un acte militant puisque c’est un gros risque: tu peux perdre tout ton travail de l’année.

There seems a new energy in the wine world which we might attribute to the natural wine phenomenon. Natural wine bars, retailers, artisan wine fairs throughout the world, new markets opening etc. Why do you think this is happening now? Is it a generational thing? The zeitgeist (increasing awareness of issues such as ethical farming, additives)? Or something else?

Yes, you could say it’s a generational thing primarily, especially in France. Our parents’ generation is rather obtuse about wine. French sixty-somethings know wine – one can’t tell them anything about it! With the younger generations, however, there’s a thirst to understand, to discover, to be surprised, whilst their elders definitely do not want to be surprised or upset!

And yes, although revelations about pesticides continues to lend credence to the phenomenon (of natural wine), that is a less important reason.

Oui, on peut dire que c’est générationnel en premier lieu, et surtout en France. La generations de nos parents reste assez obtu sur le vin. Le Français de la soixantaine connait le vin. On ne lui explique pas! Alors que les plus jeunes ont soif de comprendre, de découvrir, d’être surpris alors que les parents ne veulent surtout pas qu’on les destabilize!

Et oui, le phénomène des révélations sur les pesticides amplifie cela mais il reste encore très marginal.

Tell us about La Dive Bouteille. Can you briefly describe the fair? What was the inspiration behind the event? How has it developed?

It is the 17th anniversary of La Dive Bouteille this year! It’s a long story, [how it began], initiated by Catherine Breton the first two years because she had seen [one of the off shoot fairs] of Vinexpo. And then I resumed it by reuniting the growers in a barn – they were happy to see each other once a year, particularly when they were misunderstood at home. We could be rebellious, we could be under the radar, we always could sing and dance.

The principle has always been about good wines and good people! And it’s contagious because we bring in thousands of people from around the entire world [to join us]!

17è Dive Bouteille cette année! C’est une longue histoire, initiée par Catherine Breton les deux premières années, parce qu’elle avait vu des Off pendant Vinexpo. Et moi j’ai repris en en faisant tout d’abord une grange reunion de vignerons, heureux de se voir une fois par an alors qu’ils étaient mal compris chez eux. On a milité, on s’est déguisé, on chante et on danse toujours!

Le principe c’est toujours des vins bons et des bonnes personnes!

Et c’est contagieux puisque on fait venir des miliers de gens du monde entire!

Do you think the current system of appellation has any purpose or has it a lost a great deal of credibility with the victimisation of individual growers? Does appellation really defend origin and terroir, and honour tradition?

This role of defending [origin] still exists in some applications thanks to some visionary men and women. Unfortunately, the term is primarily used today to sell large volumes of wine, and small artisans are often denied the appellation because of the facile selection during tastings that exclude wines which stray from the “norm”. But the sad thing is that young winemakers no longer seek this designation, which nevertheless used to defend a sense of origin, and a beautiful notion of the collective.

Ce role de defense existe encore dans certaines appellations grace à quelques hommes visionnaires. Mais malheureusement, l’appellation sert surtout aujourd’hui pour vendre les gros volumes et les petits artisans en sont souvent privés, à cause d’une satanée sélection sur la dégustation qui exclue les vins qui sortent de la « norme ». Mais le plus triste, c’est que les jeunes vignerons ne cherchent même plus à obtenir cette appellation, qui défendait pourtant une origine, et une belle idée du collectif.

Do we live in a world where too much notice is given to labels and certification? Or do we need to protect consumers?

Of course we need transparency for the consumers. Wine is the only product that does not display its “ingredients”, [therefore requiring a some work on the part of the drinker]. Plus consumers still have confidence in medals and competitions!

Of course we need transparency for the consumers. Le vin est le seul produit qui n’affiche pas ses « ingrédients », il y a un peu de travail. Et les consommateurs ont encore confiance dans les médailles de concours!

What is wine journalism in France like? Is the ‘I’ll scratch your back, you scratch mine’ mentality the same there as it is in Britain, where the big brands who wield the most public relations power receive the most attention? Are editors generally up for hearing about ‘unconventional’ wines?

Our great fortune in France is firstly that there is no journalist who is as powerful as Parker. There is a gentle anarchy but very little in the way of a specialist wine press. We only talked about wine at harvest time. But now it is unfortunately only to highlight the supermarket wine fairs! Also before the big fairs we see rankings of Champagne, because they are the only ones who can really advertise and afford the publicity.

But increasingly the media – as in the specialist as well as the general press – is interested in natural wines, even if it is perhaps with an eye on the Parisian “fashionistas”.

Notre grande chance en France, c’est d’abord qu’il n’y a aucun journaliste qui se soit imposé comme un Parker. Il y a une gentille anarchie mais très peu de presse spécialisée. Le vin, on en parle seulement aux vendanges. Mais désormais ce n’est malheureusement que pour encenser les foires aux vins des grandes surfaces ! Et puis avant les fêtes, on voit des classements de champagne, parce que ce sont les seuls qui soit vraiment les annonceurs qui peuvent se permettre la pub.

Mais de plus en plus de supports s’intéressent aux vins naturels, dans la presse spécialisée comme dans la presse généraliste, parfois avec un œil un peu trop « modeux » et parisien.

Who, in your opinion, writes well about natural wine? About wine in general?

Me of course! Michel Tolmer draws beautifully! There is a great crew at Rouge et Blanc, some writers in the Revue du Vin de France, including notably Antoine Gerbelle, who’s involved with various lovely projects.

Moi bien sûr ! Michel Tolmer le dessine très bien ! Il y a une belle équipe au Rouge et Blanc, quelques plumes à la Revue du Vin de France et notamment Antoine Gerbelle qui s’envole vers d’autres beaux projets.

What was it like growing up in the Loire? How has the region changed from when you were a child to now?

It was brilliant! I grew up anchored in the Loire, and then I quickly spent time both down in the cellars and up on the slopes amongst the vines.

The Loire makes humble people. Some also say the people are too modest. Even our Charly Foucault never claimed that he made the greatest Cabernet Francs in the world. Yet it is here in the Loire that biodynamics, [helped in part by] François Bouchet who worked this way in Burgundy, received widespread press. In the Loire we have not been able to defend our grands crus. It often took people from elsewhere to wake them up. Today the Loire is one of the most dynamic regions, with rich and varied vineyards. Even the Burgundians and the Bordelais visit us in order to understand wine more fully, and perhaps to re-learn the humility that makes great vignerons.

Génial! J’ai grandi dans le lit de la Loire, puis je suis descendue très vite dans les caves et montée aux coteaux dans les vignes.

La Loire rend les gens humbles. On dit aussi qu’ils sont trop discrets. Même notre Charly Foucault n’avouera jamais qu’il fait les plus grands cabernets francs du monde. C’est pourtant d’ici qu’est partie la biodynamie avec François Bouchet qui l’a propagé en Bourgogne, plus médiatique. Ici on a pas su défendre nos grands crus. Il a souvent fallu des gens d’ailleurs pour les réveiller. Et aujourd’hui, c’est un vignoble très riche de tous ces mélanges et l’un des plus dynamique. Même les Bourguignons et les Bordelais viennent nous visiter pour comprendre, et peut-être ré-apprendre l’humilité qui fait les grands vignerons.

Tell us about your experience working in the vineyards?

That’s how I got my start! At 30-years-old, I left my job and my boyfriend to tour France’s vineyards: to work, to learn, and to drool! For me it was the only way to earn the right to speak and write about wine.

J’ai commencé comme ça! A 30 ans, j’ai quitté mon travail et mon petit ami pour faire un tour de France des vignes, pour travailler, pour apprendre, et pour en baver! C’était pour moi le seul moyen d’avoir le droit d’en parler, d’écrire sur le vin.

What made you decide to make your own wine?

[After my travels] I then had the opportunity to write. I love it. But I was missing the vines; the outdoors; nature. And above all the nature in a fantastic vineyard site that I had been waiting on for 15 years, with very old vines dominating over the Loire. One day, the opportunity came to me, as the grandfather who owned them was getting very tired. And now I spend most of my time in these vineyards. It was not the desire to make wine but the desire of the vineyards themselves!

Et puis j’ai eu la chance d’écrire. J’adore ça. Mais la vigne me manquait. Le dehors. La nature. Et surtout la nature dans un endroit que j’attendais depuis 15 ans. De très vieilles vignes qui dominaient la Loire. Un jour, c’est arrivé, le grand père les a laissé. Et j’y passe maintenant une grande partie de mon temps. Ce n’était pas l’envie du vin, c’était l’envie des vignes!

Tell us about the wines themselves – where are the grapes from, what is the terroir like, and how do you like to drink the wines?

It’s drinkable! I am very proud!

The site is a pretty, colorful hill on which the Loire comes knocking. You can see it several kilometres. The soil is rather sandy and it turns red with a little iron on the Chenin hill. The ground is strewn with large white shells. And above all, the centuries-old vines are beautiful. The place is magical!

On peut boire les vins! J’en suis très fière!

C’est une butte assez colorée sur laquelle la Loire vient cogner. On la voit sur des kilomètres. L’ensemble est plutôt sablonneux et il devient rouge du côté des chenins, un peu ferreux. Le sol est jonché de gros coquillages blancs. Et dessus, les ceps centenaires sont magnifiques. L’endroit est magique!

How many clay vessels do you have? What motivated you to make a wine in terracotta and where did you get them from?

I have two qvevris which come from Georgia. When I tasted my first macerated wine, I was really moved. And seeing these wonderful objects, inimitably crafted, I really wanted to use them. We do things differently, with respect to this craft, because the Georgians are the only ones who have never stopped making wine, and because it is a chance to create something, a gift.

J’ai deux qveris, qui viennent donc de Géorgie. Quand j’ai goûté mes premiers vins macérés, j’ai été vraiment émue. Et en voyant ces objets merveilleux, ce travail inimitable, j’ai eu très envie d’en utiliser. On fait les choses différemment par respect pour ce travail, parce que ce les géorgiens sont les seuls à n’avoir jamais cessé d’en fabriquer, parce que c’est une chance d’en avoir, un cadeau.

How does fermenting in clay affect the shape/texture of the wine? How does the actual fermentation differ compared to stainless steel or wood?

I think that the earth is the closest material to grapes. Clay receives the grapes gently, and like magic, fermentation begins soon after, and is never violent. Plus there is no circle of iron, as there is for wood. I think the life (of the wine) is made more harmonious by this bulbous and pointed form.

It seems to me that there is more harmony in the wine. Since the skins are macerated for nine months, the wine should be harder. But instead there is more creaminess; a velvety quality; greater unity. And more different facets.

Je pense que la terre est le matériau le plus proche du raisin. Alors elle le reçoit avec douceur. Et comme par magie, les fermentations commencent très vite, et ne sont jamais violentes. Et puis il n’y a pas de cercle de fer comme pour le bois, et je pense que la vie se fait très harmonieuse dans cette forme ventrue et pointue.

Il me semble qu’il y a plus d’harmonie dans le vin. Les peaux ont pourtant macérées pendant 9 mois, le vin devrait être plus dur. Mais il y a plus d’onctuosité, de velouté, d’unité. Et plus de facettes encores.

What was the winemaking process like for you?

A holiday! For my first vintage, it was not easy in the vineyards! I did everything by hand, and it was very hard during the rainy summer to apply the preparations. Then when it came time to harvest, the Suzuki fruit flies arrived! We had to chuck a lot of grapes onto the ground. I sometimes harvested and removed the grapes damaged by fruit flies one by one by myself…Thus when the grapes were finally in the tanks, intact, I did not want to do anything. They were safe. They could not make me stupid – I had worked so hard!

For the qvevris, I did everything by hand, without pumps or machinery, just by gravity. Whenever I had to touch the qvevri, I called Paul, a very nice person who is also fascinated by the vessels. As for bottling, we filled them each one by gravity.

A holiday! Pour mon premier millésime, ça n’a pas été facile dans les vignes! Je fais tout à pied et pour les traitements, c’était très dur avec cet été pluvieux. Et puis quand on a voulu vendanger, les drosophiles Suzuki sont arrivés! On a mis beaucoup de raisin par terre. J’ai vendangé toute seule parfois et enlevé les grains piqués par les drosophiles un par un…

Alors, quand les raisins ont été à l’abri dans les cuves, je n’ai rien voulu faire. Ils étaient à l’abri. Ils ne pouvaient pas me faire de bêtise, j’avais tellement travaillé!

Pour les qveris, j’ai tout fait à la main, sans aucun moteur, par gravité. A chaque fois que je devais y toucher, j’appelais Paul, une très belle personne fasciné aussi par cet objet. Pour la mise en bouteille, on a rempli une par une, par gravité.