You take the venom out of a cobra and what have you got? A belt.

Glenn Quagmire – Family Guy

I am a sucker for observational comedy. You know the kind: What’s the deal with airline food? Have you ever noticed how tiny packets of peanuts are so hard to open? There is no punch line, just simple bemusement/mild outrage about life’s little absurdities.

In the interest of sweating the small stuff, I will pose a few rhetorical questions. Why is it that I am being assailed by so many people trying to sell us non-alcoholic beverages at the moment? My life’s energy is devoted to extolling the virtues of natural wine – and selling it. Whereof should I repent my sins and advocate for the non-booze juice?

Yes, what’s the deal with non-alcoholised wine? Or do I mean de-alcoholised wine? For starters, I don’t even like the word – too many syllables. More of a mouthful than the actual drink itself. And then the claims and general marketing hoo-ha surrounding it. Are you trying to sell me a lifestyle choice or persuade me that change for the sake of change is a good thing? Dry January and Lent are thankfully distant memories. Time to resume normal wine bibbing.

I get it – we need alternatives to booze. I get it – healthier lifestyles are a good thing. This is common sense. What I don’t get is that it is a bandwagon. Fashionista puritanism, blessed virtue signalling. It is not about the booze per se, but the person who is imbibing.

I’ve examined the credentials of many of these alternatives and registered the pr-puffery. They don’t cut the non-spicy mustard. These versions are not alternatives – they are different drinks in themselves.

The narrative of the pious alternative is a satisfying one. The food industry has long explored vegetable alternatives to meat. Burgers resembling meat patties but are made from compressed beetroot and release red juices when they are grilled. Fake bacon (facon) that looks the part and sizzles appropriately in the pan.

Yet, just because it presents as a rasher and can fry like a rasher does not make it bacon.

It is the thermal breakdown of fat molecules reacting to the nitrites used in curing that give bacon its baconiness. Without this prime constituent facon is an empty vessel. (Not a sentence I write very often.)

Despite the fact that consumption has overtaken beer in the U.K., drinks manufacturers are concerned that young people – in particular – will gravitate away from wine towards something else. Big brands are constantly agonising on how to appeal to new generations of drinkers, how to remarket their offerings for this emergent tribe. And non-alcoholic drinks sound more interesting than teetotal ones. The latter smacks of denial, the former an active lifestyle choice. And appending the word wine to a drink gives it even more credibility.

Wine can be so much more than a gateway drug to unbridled alcoholic consumption. It is gastronomic. It is nourishment. It has layers. It has origin and stories.

With all respect to the alternatives, the denuding processing that goes into removing alcohol or creating something with a vaguely similar appearance, flavour, or texture, is nothing to do with the culture of wine or winemaking itself, and everything to do with creating a marketable beverage.

On the other hand, one could equally ask (about wine): do we need a product in our lives that is effectively chemically-processed grape juice from industrially-farmed monocultural vineyards that eat up nature’s resources and yields little pleasure other than the hit of confected flavoured alcohol?

What does the word alcohol mean to you? For me, it conjures a vista of bottles of pure spirit destined to be taxed by customs and excise. It is the distillation of all drinks down to the essence of societal misrule and temperance tut-tutting. Alcohol has become a pejorative term for creating behaviours and conditions that need to be legislated against. Dionysus behind bars (and I don’t mean wine bars).

The etymology of alcohol is as wobbly as one might have suspected. The word itself is Arabic, which may seem odd, given that Islam is a teetotal religion, but when the Arabs used the word alcohol, they weren’t referring to falling down water. Alcohol derives from al (the) kuhul, which was a kind of make-up (one still used in eastern European countries as a form of eyeliner), necessary to apply to disguise the tangible effects of one too many.

As kohl is essentially an extract and a dye, alcohol started to mean the pure essence of anything. (There’s a 1661 reference apparently to the alcohol of an ass’s spleen – which is what a certain food critic thinks all biodynamic wines taste like), but it wasn’t until 1672 that somebody at the Royal Society had the bright idea of finding the pure essence of wine. What was it in wine that made you drunk? Was it the unicorn tears of a highly sought after Jurassic rarity, or something even more essential? Soon wine-alcohol (or essence of wine) became the only alcohol anybody could remember until everyone got so hazed on fumes that wine alcohol was shortened to wine. Fewer syllables, less shlurring.

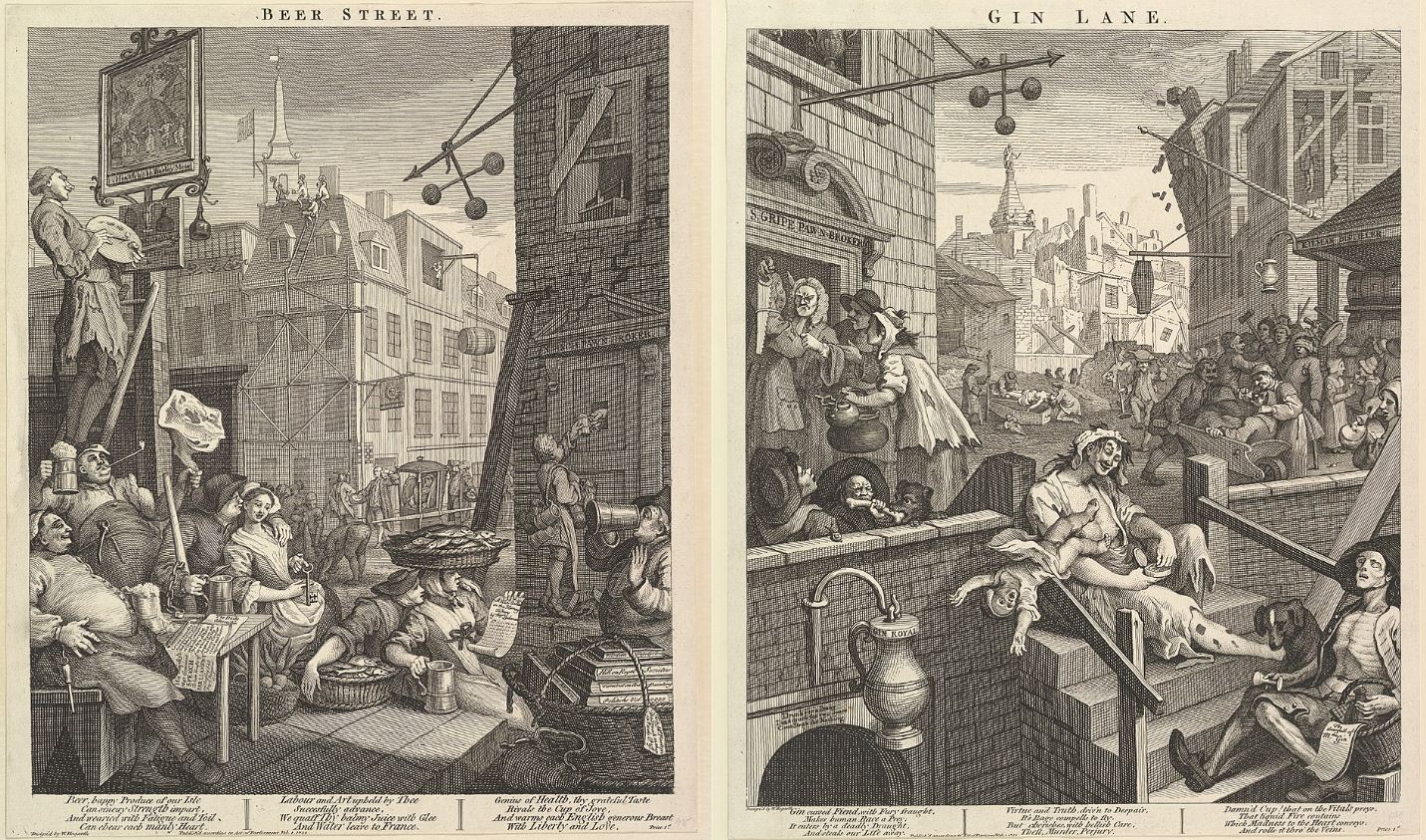

So much for etymology. Whereas wine had been associated in religious culture with spiritual (not spirituous) intoxication (The Book of the Winebringer by Hafez; The Rubiyat of Omar Khayyam and so forth), it eventually got roped in – by association – with immoderate drunkenness. The demonic power of drink (in its modern incarnation) dates back perhaps to the craze for gin, the bathtub rather than the craft version.

One of the earliest known legislative actions on alcohol was during the ‘Gin Craze’ which spanned across the late 17th century and early 18th century. Due to political and religious conflict between Great Britain and France, the Government passed a range of legislation to restrict French brandy imports and increase British gin production. These proved successful in their aims and the consumption of gin amongst the population increased dramatically. The average person was drinking six gallons of gin per year. Gin provided an escape for the 18th Century poor, and the insatiable demand for the liquor was soon linked to crime, poverty and a soaring death rate. The drink became known as ‘Mother’s Ruin’ as mothers began to neglect their children in favour of the drink, and between 1730 and 1749, 75% of children born in London died under the age of 5. Between 1729 and 1751, eight Gin Acts were introduced in an attempt to restrict the availability of the alcohol and curb this “social evil”. However, this did not curtail the widespread alcoholism, but instead forced the distillation and consumption of gin underground, creating a black market for bootleg gin. The Gin Act 1751, commonly known as the Tippling Act, was the penultimate Act in a series of eight, which succeeded in reducing the consumption of the alcohol, with the reason for its passing stated as: ‘‘…the immoderate drinking of distilled Spirituous Liquors by Persons of the meanest and lowest sort, hath of late years increased, to the great Detriment of the Health and Morals of the common People’.

Scroll forward to the Victorian era and the growth of temperance movements and teetotalism and then various licensing acts that restricted the sale of intoxicating liquor.

Excise duties exist to discourage the purchase of alcohol. Minimum pricing per unit has also been used in Scotland. Alcohol is something around which public health policy is framed.

There is a widespread political view that sees human beings as needing to be protected against their own inborn weaknesses and baser instincts, that those who use alcohol as means to escape may end up destroying themselves and whose desire to get drunk potentially may lead to crime and abuse and becomes a burden on the health system.

The state may tax and legislate as much as it likes, but balanced consumption is always the choice of the individual. Those that choose wine as their preferred beverage may enjoy it for its taste as well as the social lubricant of alcohol. But the alcohol is important in conveying aromatics and flavours, and the way that wine is made (from the farming to the winemaking) is integral to our enjoyment of the drink. In the end, no matter how clever or complex the processing that goes into manufacturing the project, describing a non-alcoholic drink as a wine alternative is a false equivalence.