Of natural wine origins and movers-and-shakers

Literature is riddled with examples of the unreliable narrator from Nelly in Wuthering Heights, Pi Patel in Life of Pi, and Lemuel Gulliver in Gulliver’s Travels. And, arguably, me in this blog. Natural wine has a largely uncharted history. Who really knows who said what to whom and when, whose idea it was to classify wines as “natural”, and who first produced wines in an avowedly natural wine. To paraphrase the opening of Goethe’s Faust: In the beginning was the word… no, in the beginning was the deed! Once upon a time, all wine was wine. And people did add stuff to it to preserve it or bolster it in some way. And many just made fermented grape juice as nature intended.

Natural wine culture is something different and there are different versions how these wines emerged into the modern wine world. The past is a foreign country, and we re-arrange the events to fit a neat narrative sequence, when in reality the truth is a lot more complicated and a lot less tidy. Best to say that there are known natural wine movers-and-shakers and there have been certain convergences at specific moments – usually small groups of vignerons clubbing together, exchanging ideas and information, and creating what is generally described as a movement.

In Part Two of this 1000th blog anniversary post, I will continue weaving my original bullet-pointed ideas (in a different order to previously) from an alternative natural wine manifesto first published in the early 2000s (I forget when exactly) – and cut with some later revisions – into a discursive essay touching on the history and culture of natural wine, the controversies that these wines engendered over the years, how the genre is currently perceived in the market, and finally, on a personal note, detailing the pleasure and otherwise I have derived from writing far too many blogs about the subject.

(By the way, the bold font denotes the original manifesto statement followed by the argument, and the italics are comments interpolated ten years later).

1. Who is the leader of the natural wine movement and articulates its philosophy? Probably whoever chooses to – over a drink. We are all Spartacus in our cups. Think camaraderie, copinage and comity with these guys, not po-faced table-thumping, self-indulgent tract-scribbling and meaningless sloganeering.

*The increasing number of wine fairs, forums and associated groups with charters suggests that there are people who wish to assert that natural wine is a recognised movement with specific parameters. Because of its political diversity, and because the groups and associations tend to splinter and then splinter again, it is difficult to say who is the heart or the head of such movement.

I am not going to reference Jules Chauvet, Jacques Néauport or Marcel Lapierre. Or the biodynamic producers in the Loire who influenced and mentored many other vignerons. I won’t even mention seminal influences such as Alice Feiring, Sylvie Augereau, Pascaline Lepeltier, Eric Narioo and Joe Dressner. Nor allude to Pierre Jancou and Paris natural wine movement. The early heroes of natural wine know who they are. What they wrote and what they did, their passion and their commitment led to fundamental vini-cultural changes not only in their respective countries, but throughout the world of wine.

2. The heroes of the natural wine movement are the growers. There are mentors and pupils, there are acolytes and fans, but no top dog, no blessed hierarchy, no panjandrum of cool albeit some are born cool, and some have coolness thrust upon them. Some growers are blessed with magical terroir; others fight the dirt and the climate, clawing that terroir magic from the bony vines. They are both artisans and artists. What impresses us about the best natural growers is their humility before nature and their congeniality, a far cry from the arrogance of those who are constantly being told their wines are wonderful a hundred times over and end up dwelling in a moated grange of self-approval.

When the history of natural wine is written (or written again) there will be some stand-out personalities. The narrative, rather than being fluid and inevitable, meanders and lurches. Without Chauvet and Lapierre and the BD guys in the Loire and some of the Triple A growers in Italy, perhaps natural wine would have taken even longer to cause ripples. And you must give enormous credit to the very few writers and commentators – and importers – who put their heads above the parapet and championed this breed of vigneron.

Natty UK

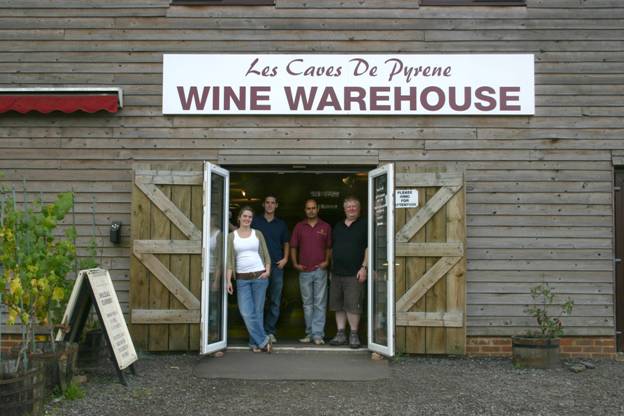

Let’s give ourselves (Les Caves) a teeny pat on the back. Once upon a time when we were but a teeny amateur company knee-high to a Diam cork with barely two straw pennies to rub together, we were hot stuff. I mean smokin’ hot like a barbecue sauce created by a Mexican chef using The Merciless Peppers of Quetzalacatenango …grown deep in the jungle primeval by the inmates of a Guatemalan insane asylum. The flavour of the month, the year, even if that flavour was too spicy for some. We were a classic example of unknown rags graduating to slightly more recognisable rags, and, bewildered to have risen without trace, we tripped the light fantastic for a moment in the sun.

Once upon a time when we were but a teeny amateur company knee-high to a Diam cork with barely two straw pennies to rub together, we were hot stuff.

It helps to be the first over the wall in several arenas. It is well known that Les Caves grabbed the natural wine bull by its steaming horns. This catapulted us into the limelight whether we wanted that or not. Not that it had anything to do with identifying a putative trend and riding it like a bomb, rather it was the result of liking a certain style of wine and hoping others would come around to our taste. How cool to buy and sell something that you might want to drink with pleasure yourself. One of the early catchphrases of our company was: If no-one likes the wine, we’ll drink it amongst ourselves. Yes, the nothing-ventured philosophy came with a complimentary wine glass to consume one’s mistakes. Others saw it differently – that with our studied air of insouciance we were cunningly manipulating taste, brainwashing customers, flying a flag, riding a bandwagon etc. Because we liked something a bit different, we were de facto fundamentalists.

The rest, as they say, is history.

We didn’t invent natural wine, of course, but we did open the UK’s first natural wine bar and organise the first natural wine fairs (small events prior to The Natural Wine Fair in 2011 and the Real Wine Fair which emerged from that). We have championed the wines for as long as we were aware of their point of delicious uniqueness. Or unique deliciousness. We will always remember our first respective encounters with a natural wine, and the shock of the epiphanies, which galvanised us to seek out further examples of these weird (yes) and wonderful (yes) wines, and which in turn eventually catalysed into the desire to open a wine bar celebrating such wines.

The idea behind Terroirs was a simple one. Create an environment with good food, unpretentious service and put together a wine list comprising artisan growers who worked with minimal intervention. Show the sheer diversity of natural wines – from the irreproachably die-straight to the updialled funk. Create a buzz about wine (any wine, all wine), encourage people to talk about it, to experiment, and open themselves to different taste sensations. Although Terroirs became known as a natural wine bar, it was not consciously aimed at a hipster crowd, in the sense that we wanted to attract drinkers of all tastes, rather than a clique of supporters (not that such a thing existed in London at the time!). What made it so alternative, is that it was the antidote to the branded chain wine bars that currently dominated the so-called wine scene in London. And the only Pinot Grigio on the list? No thrice-filtered milquetoast pabulum, if you please, rather a brooding, turbid pink-orange skin-maceration version from Dario Princic served wild in a decanter. For a lot of wine people, Terroirs was the other side of the looking glass. And that was a fun place to be.

Originators in the UK perhaps, we were only playing distant natural wine catch-up to our cousins across the channel, who were years ahead in having a dynamic wine culture. They did indeed order these things differently in France. How exciting it must have been to be in Paris during the stirrings of the natural wine revolution.

Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive,

But to be young was very heaven!

The natty wine bars and cavistes in that city became the stuff of legend. French wine fairs championing the efforts of so many small vignerons were also places of pilgrimage, the rendez-vous locations for all natural wine lovers across the world.

When things start to trend, then commentators describe it as a moment. Natural wines, the bars, shops and fairs, the philosophies articulated by some of its exponents, were viewed as an alternative to the other wine world – call it the traditional, conventional, hierarchical, Parkerised one…

When counter-culture (natural wine, in this case) meets traditional culture, there is inevitably friction. When natural wine was a callow youth, an inconsiderable trifle, it was not deemed a threat to the wine establishment in this country. The establishment, in this case, being an agglomerate of the commentariat; oenologists; supermarket buyers; fine wine purveyors; generic associations including appellations; companies and brands making wine on an industrial scale. Adherents of natural wine are against homogeneity, pettifogging standards, against using chemicals in vineyards and poisoning the land, against adding and subtracting from wine, against denaturing, in short, and pro the liberation of wine made without an obvious safety net, the excitement of tasting wine that is alive, deviant, and that embodies the aesthetic of wabi-sabi. Interestingly, a number of natural vignerons see themselves as defending local culture by returning to traditional methods of farming, protecting heritage grape varieties, involving the community, and so forth.

Jonathan Nossiter describes the adherents of natural wine as participants of “cultural insurrection”, by which he meant a collective desire to use farming and natural winemaking to generate social change. Art, music and cinema has largely lost its power to shock, to engage intellectually and transform people’s lives. Natural wine has stepped into the breach and a new-wave of artisan producers are the people challenging convention and homogeneity and a conservative and inward-looking wine industry that serves the interests of institutions rather than caring for the interests of small independent farmers.

It helps to be the first over the wall in several arenas. It is well known that Les Caves grabbed the natural wine bull by its steaming horns. This catapulted us into the limelight whether we wanted that or not. Not that it had anything to do with identifying a putative trend and riding it like a bomb, rather it was the result of liking a certain style of wine and hoping others would come around to our taste.

If we think of ourselves to be individuals rather than consumer-sheep, we need to express ourselves through the medium of choice. Wine has always been marketed as a defined product. A product at a specific price point. A product to collect and trade. A product to get you drunk. A product for a commercial purpose. Where is the joy in that? If it makes me smile to myself, if it makes my spirits soar, if it chimes with what I am feeling or conjures a long-lost memory, then wine is real, it lives. I have been told by wine educators that any wine has to be representative of a specific style, so that consumers know what they are getting. All Sauvignon Blanc, for instance, should smell and taste of the Sauvignon archetypes (herbaceous, tropical fruit, cat’s pee). I do not believe in type-casting wine and once narked off a food critic by quoting Emerson’s observation that “a foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.”

Pierre Frick – thinking and drinking outside the box

Conventional thinking objectifies wine as a commodity. For me, natural wines challenge this notion and move us towards a different form of engagement. Pierre Frick writes about this subject in his book Du Vin, de l’Air, apparently inspired by observing how different people react to the same wine. If we are what we eat, we are also what we drink, and how we appreciate wine indicates (to a greater or less extent) what our values are and the way we approach life. Frick sees various wine responses as emblematic of certain social and philosophic tensions. He implies that orthodoxies result from continuous classification and compartmentalisation. One may develop this further and examine how political systems are designed to make individuals conform, and big corporations, by definition, view humans as consumers, cyphers to be conditioned to respond in a particular way. We need to encourage people to think of (and value) themselves as individuals, not to care what the majority thinks, and look inside themselves and to their feelings to guide their responses.

Frick begins his mini-thesis by describing two extreme types of taster: the academic and the adventurer. The academic, or professional, deconstructs wines on the basis of acquired knowledge. For them tasting is a matter of professional decorum, since they are tasting not just for themselves, but for knowledge itself, a knowledge that will be codified and organised and brought to bear at a later date. The adventurer, meanwhile, is intuitive; he or she prefers to sense the wine rather than judge it right or wrong. Normative values do not apply – the here-and-now is what matters, the very experience of tasting which excites the imagination and arouses the emotions.

Milling the mille

Its’s the tail-end of 2023, and, big Trumpet Voluntary, (composed by Jeremiah Clarke and arranged by Sir Henry Wood), and I have now tapped out one thousand blogs on natural wine. A lot of no-sulphur has flowed under the bridge. Yes, dear reader, I counted them, and as with the enumeration of sheep, fell asleep. Wine, let alone the natural side of it, is not an inexhaustible subject and I feel that I have mined it beyond the centre of the earth and shaken all the grist from the mille. A lot of metaphors have been mixed along the way. I’ve actually written a lot more than a thou, but the period between 2007-2012 now counts as the literary Dark Ages as my unsolicited thoughts were only mailed weekly to unsuspecting people in my address book. And, as we all know, if no-one reads a blog, does it really exist??

Joking aside, it’s as endlessly fascinating for me, as it is endlessly boring for my imaginary audience, to delve into mildly controversial ancillary topics surrounding wine, and natural wine in particular. In what other written forum might one be able to dissect the very nature of taste? Speak passionately about the ethics of farming? Shine a light on desirable and undesirable practices in the wine trade? Celebrate a wine’s beauty for it being in the eye of the beholder rather than a mark on a one-hundred-point scale?

Natural wine is here to stay. Present and correct. Or incorrect, if you feel you have to hate the murky stuff. Farmed, made, imported, sold and consumed. Its burgeoning popularity has, however, justifiably caused some of the original movers-and-shakers to wonder whether the revolution is being taken over by opportunists. Certainly, the number of producers who make low-intervention wines has grown exponentially, some of whom may undoubtedly have latched onto the marketing potential associated with these wines. We merely note that the profusion of new growers and new wines, and new companies hawking them.

3. If natural wine is not sufficiently equipped/bothered to organise itself into a movement why should anyone take it seriously? To paraphrase Groucho Marx: a natural winegrower wouldn’t want to belong to any club that would accept him or her as a member. The world of wine is far too clubby and cosy. In the end it is about what’s in the bottle of wine on the table. A movement is an organisation that creates rules and appoints spokespersons. Natural wine has always been more organic with people working singly or in small groups to make the best wines they possibly can.

That was indeed then. Perhaps the world was a more innocent place. The wine world is afflicted by politics and consumerist necessity. It is also driven by personalities. Some of those personalities would like to ensure that natural wine has an exclusive reputation and clearly demarcate points of difference with other wines. A natural movement with a bullet-point charter would be proof of oversight to work against the criticism from those who complain that consumers are being hoodwinked by a purposely vague designation.

4. But we do know who they are, these growers? Some are certainly well known, some fly under the radar. Yes, some of them are best mates; they drop in on each other, share equipment (including horses!), go to the same parties, wear quirky t-shirts, attend small salons and slightly larger tastings. And quite a few don’t because they have so little wine to sell (such as Metras, Dard & Ribo…) By their craggy-faced visages, rough manners and horny hands shall ye know them. But their activity is not commercialised; there is no single voice that speaks authoritatively for the whole natural wine movement – and therein lies its beauty, so many characters simply getting on with the job without hype or recourse to corporate flimflam.

This point deserves re-evaluation. There may be anything between 500 – 1000 producers making what I call natural wine. It is very tricky to keep track, as many have risen without trace in the last couple of years. Caveat: To make a wine without sulphur is not itself enough to be working within the spirit of natural wine, although it is kind of start. The hard yards and miles must be done first in the vineyard. The assessment of who is making natural wine is subjective, and therefore controversial. As some producers seek to capitalise on natural wine status, we are witnessing instances of envy with unsubstantiated allegations about vineyard and winery practice, all of which arises out of personal dislike or a hidden commercial agenda. Secondly, the importers and various wine fairs have become the voices of natural wine. There are differences of opinion, and more voices means more clamour and less clarity.

Once one might have numbered them on the fingers of one hand, now there are wine fairs, big, medium, and small, taking place almost every day in the tasting calendar. The small ones have often splintered off the bigger festivals, meanwhile many of the larger ones have taken on corporate sponsorship.

This merely reflects the evolution of any movement. It may be born as a form of counter culture with its own set of ideals and ethical values, and as it becomes more widely recognised and even popular in certain quarters, people will jump on the bandwagon, and the original ideals may be diluted. The free spirit of natural wine has been adapted to professionalism and pragmatism. The wine trade, its growers and wine merchants, need to make a living, and purity of purpose is a luxury that no-one can afford. Alas.

When asked recently by a journalist what I believed had changed over the last decade for the better and the worse in the natural wine world, I remarked that I felt something had been lost. I can’t really put my finger on it. Perhaps, it’s nostalgia for a supposed age of innocence. I know that I romanticise like crazy, but equally it is impossible to ignore one’s sense of the past even if it is viewed through unfiltered rose-tinted specs. The wines I first encountered, that set me on my path, were some of those wines were the most memorable I have ever drunk. I miss their raw energy, their spikiness, their unfiltered quality. Faulty winemaking notwithstanding, natural wines seem cleaner now, doubtless the result of more knowledgeable and discriminating winemaking. Gains in cleanliness may well be at the cost of spirit. At the beginning of my journey, I encountered so many wines that were brilliant in a particular vintage (just one vintage) because they were so wild, whether it was nature, luck, the alignment of the stars, or a winemaking accident. Never again did I taste a wine from those same domaines that thrilled me in the same way. Then I look at all my favourite wines and notice that (almost invariably) I love the old-fashioned style, the wines on the edge, the wines that are, and have always been, on the brink of faultiness.

I believe that in the natural wine house there are many mansions.

The more modern exacting style of natural winemaking makes for beautiful wines in the right hands. They are not wild or funky. They are pristine and precise. They are often appreciated by those who enjoy more classic wines. These wines are delicious, be they easy-drinking or super-complex. The other style, alluded to in the previous paragraph, feels more raw, less controlled, less fine, but is capable of engendering a deeper emotional response. Obviously, this is not a scientific analysis and conclusion, much more of a gut feeling about certain wines.

Back down to earth

When you cast aside wine trends, semantics, history and ownership of a concept, you are left with what is truly important. When we opened Terroirs, although we conflated natural winemaking with good organic farming practice, perhaps it was the idea that you could make wine without adding anything that caught the imagination of drinkers. No-intervention was what natural wine was pegged to, easier to grasp than organics (a term butchered by supermarkets), and biodynamics (which to most people who had heard of it was more than organic with some voodoo “science” added). Yet natural wine evolved out of (and would be meaningless without) sustainable farming: from organic and biodynamic to regenerative. Farming and nature make the grapes what they are. The better the farming, the healthier the vineyard, the better quality of grapes that are produced. Judith Beck told me that when the full effect of biodynamic conversion was realised, the vineyards gave back so much more in the way of quality (grapes). Natural winemaking is an extension of best farming practice, and although wine is, of course, the end of the process, what matters most is that is made with maximum respect for the environment and for nature itself.

Coda

So, rinse and repeat, 1000 blogs –the churn of news, reviews and opinions of a decade plus. Perorations, thunderings, encyclicals, reviews, parodies and obituaries. I have written about every aspect of wine, often with a thimbleful of real knowledge and a barrel-load of unfiltered (that word again!) opinion. Rereading some of the pieces, I can see I was “gallantly” defending the honour of natural wine at a time when no-one really had a positive word to say. Bar the odd strategic rebuttal, this offence-as-defence has now become unnecessary and contrarianism for the sake of it, is a waste of time and energy. I began my original natural wine manifesto with a plea for tolerance, that we always want to accentuate the positive and eliminate the negative and to speak joyfully about the wines we love rather than criticise the ones that we don’t.

The manifesto ends thus with the following arguments, refutations and celebratory statements.

5. Natural wines are incapable of greatness. Let us put aside for a moment the notion that good taste is subjective and transport ourselves to our favourite desert island with our dog-eared copy of the Carnet de Vigne Omnivore, the natural wine mini bible. Because the natural wine church has many mansions; you will discover a constellation of stars lurking in its firmament. Natural wine growers don’t work according to precise calibrations of sulphur levels; instead, they seek to express the quality of the grapes from their naturally farmed vineyard by keeping interventions to a bare minimum. In certain regions such as Beaujolais, Jura, and the Languedoc-Roussillon, virtually all the great names are what we might term “natural growers”. Again, we don’t seek to make anyone join the family or fit in with an overarching critique. Natural wine is fluid, in that vignerons who are extremists, row back from their position, whilst others, who start out conventionally, feel emboldened to take greater risks by reducing the interventions.

Since writing this I have decided that greatness is purely an illusion. What many people have traditionally called great are wines that are seemingly “architectural”, constructed to such a level that you can see all the layers attaching to each other. For me, greatness is far more elusive, tantalising – and personal. Wines that have this quality throb with energy, they open and close and open again, they resist tasting notes, they inspire – initially neither like nor dislike – but feeling, and trigger all the senses to respond acutely.

6. Natural wines don’t age well. Hit or myth? Myth! It is true that many natural (red) wines are intended to be drunk in the first flush of fruit preferably from the fridge. So, sue them for being generous and gouleyant. Ironically, many white wines with lees-ageing, skin contact and deliberate oxidation have greater longevity and bone structure than red wines. But it is simply not true to assert that natural wines can’t age. A 1997 Hermitage from Dard et Ribo was staggeringly profound (et in Parkadia ego), old magnums of Foillard’s Morgon Côte du Py become like Grand Cru Burgundy as they morgonner, some of Breton’s Bourgueils demand that you tarry ten years before becoming to grips with their grippiness. Last year, we tasted a venerable 10.5% Gamay d’Auvergne from Stéphane Majeune, as thin as a pin, and still as fresh as a playful slap with a nettle, whereas the conventional big-named Burgs, Bordeaux, and Spanish whatnots alongside it all collapsed under the weight of expectation and new oak. If the definition of an ageworthy wine is that you can still taste the knackered lacquer twenty years after, then give me the impertinence of youth any day.

The health of the wine lies in the bone structure and not in the flesh (which will wither). Some natural wines have amazing purity and minerality (that word again), a structure built on the most solid foundations (great farming, great grapes) and sensitive winemaking (long elevage, the best kind of flavour and texture extraction).

7. Natural wines are unpredictable. You said it, kiddo. And three cheers for that. Their sheer perversity is embodied in these lines by Gerard Manley Hopkins:

And all things counter, original, spare, strange;

Whatever is fickle, freckled (who knows how?)

With swift, slow; sweet, sour; adazzle, dim…

8. My glass is empty. As it should be – it was a glass of delicious Crozes-Hermitage Rouge from Dard & Ribo.

Natural wine is a recognition that not everything can be made in a petri dish. That to capture the spirit of the vineyard and the flavour of the grape and quirk of the vintage, one must let go. Natural wine is the freedom to get it wrong, and the freedom to get it very right indeed. It relishes and embraces the contradictions and dangers inherent in not being in control.

We want people to drink without fear or favour, not worry about right and wrong, leave critical judgement on hold, and enjoy wine in its most naked form.

“For as we would wish that a painter who is to draw a beautiful face, in which there is yet some imperfection, should neither wholly leave out, nor yet too pointedly express what is defective, because this would deform it, and that spoil the resemblance; so since it is hard, or indeed perhaps impossible, to show the life of a man wholly free from blemish, in all that is excellent we must follow truth exactly, and give it fully; any lapses or faults that occur, through human passions or political necessities, we may regard rather as the shortcomings of some particular virtue, than as the natural effects of vice; and may be content without introducing them, curiously and officiously, into our narrative, if it be but out of tenderness to the weakness of nature, which has never succeeded in producing any human character so perfect in virtue as to be pure from all admixture and open to no criticism.”

—Plutarch, Parallel Lives

As a company, and as individuals, we have continued to evolve as our opinions and tastes naturally change over time, and although we have grown, we still subscribe to the “small-is-beautiful” view of the world.

Our connection with natural wine has helped to define us as a company. We feel blessed to have met some amazing people along our journey. So many have become dear friends and part of the wider Les Caves “family”. We enjoy being a small wine community within a greater wine community. The Alternative Wine Manifesto was written in the very early days of natural wine when we are all a bit more naïve. As a company, and as individuals, we have continued to evolve as our opinions and tastes naturally change over time, and although we have grown, we still subscribe to the “small-is-beautiful” view of the world. We did it, and we do it, our way. The wider world of natural wine is also very different now with ambitious, competitive and commercially savvy operators aggressively marketing their wines and services. Meanwhile, the spectrum of wines available to consumers has broadened to an incredible degree. There are now so many more independent vignerons doing their own thing and so much more choice as a result.

I should write a sentence that ties everything together neatly, but when a piece is so fragmentary and digressive, touching variously on the history, the culture, the controversies, the personalities and practices in this curious locale that I call “the natural wine world”, no single observation can sum it all up. In some previous blogs, I have ended with a plea for tolerance and respect. We may love drinking naturally-made wines, and we always express support for the idea behind the wines. In the end, however, we are just talking about wine, a fascinating subject, but it doesn’t take much to see that its controversies don’t amount to a hill of beans in this crazy world.