I have been in more than one cab (but not at the same time), and when asked what I did for a living, explained truthfully that I was involved in a wine company that imported and distributed wines. At this point, the driver might perhaps say something like: “I don’t like white wines, but I do drink Chilean reds”. Or: “I like a good Rioja on special occasions”. Or: “My wife only drinks white wine.”

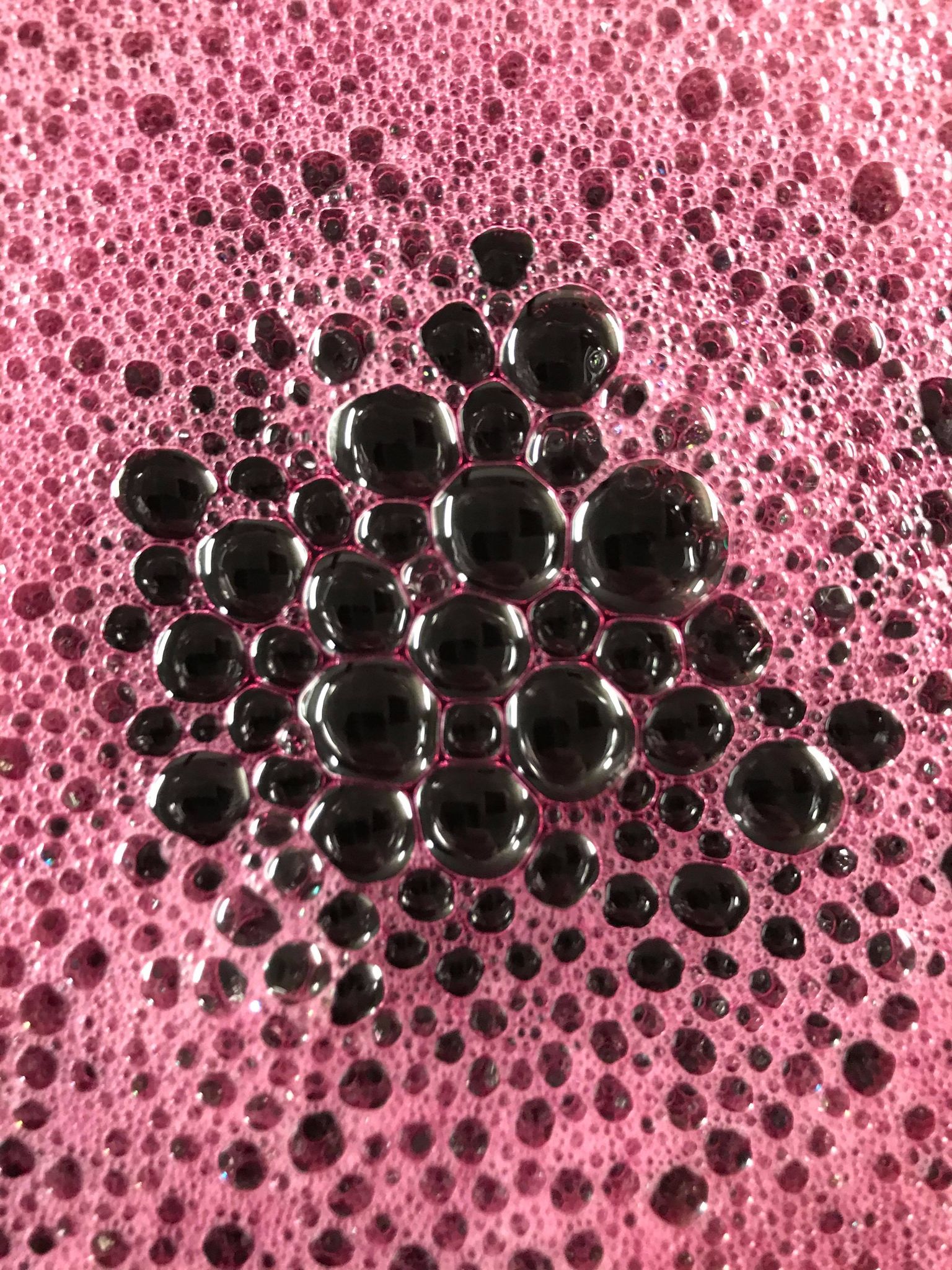

Our earliest awareness of wine as a subject worth studying is arguably when we begin to classify individual wines by their colour. When we are naming things, the simple certainties are always reassuring: this is white; that is red; this is rosé, and that has bubbles. Most wine lists reflect these broad, if simplistic, categories and the very human predilection for binary choices. However, there’s white and there’s white, and there’s red and there’s red. And then there is orange, just to throw a juicy spoke into the system’s wheels.

Orange wines may be not as old as the hills, but likely they are as old as wine itself. Wines may achieve this colour by means of skin-maceration, long or short, or oxidation – and some are undeniably more orange than others. In fact, some are not orange in the colour-literal sense. The reason why this style of wine captured imaginations when they first appeared on the scene, is due to a combination of the very revolutionary idea of the wine (in other words, using red winemaking methods to make white wines) allied to the sheer exuberance of the colour of the wines, their different aromas, and flavour profiles. In the world of classical musical structure and pop melodies, they were akin to modern jazz.

Our earliest awareness of wine as a subject worth studying is arguably when we begin to classify individual wines by their colour. When we are naming things, the simple certainties are always reassuring: this is white; that is red; this is rosé, and that has bubbles.

We will return to orange wines later, but suffice to say, that their existence serves to make us re-examine old certainties about reds, whites and rosés. The idea that one would classify Tondonia white, for example, within the same “colour spectrum” category as a typical Marlborough Sauvignon is absurd. They may be part of the wider family of wines, but not more than that. So, if differentiating and grouping wines by colour is only (grape)skin deep, then some sort of more pertinent sub-division and reclassification is desirable. Sorting wines by respective countries of origin takes us no closer to the heart of the wines themselves. Instead, it is the many dozens, hundreds even, of farming and winemaking decisions, that shape the nature of the contents of the bottle.

Wine assessment begins with noticing what the wine in question looks like. In red wines, rich colour in red wine has often been associated with puissance, even high quality. In former times, the weedy clarets of Bordeaux were often augmented with rustic wines from up-river country regions, and even wines from other different countries. Pale, underwhelming red Burgundy might be bolstered by judiciously mixing with Syrah from the Rhone. Algerian red was traditionally used to give a whack of colour and alcohol to the dilute bulk wines made from Aramon in the Languedoc.

If colour doesn’t come naturally, and you don’t use the aforementioned ancient disreputable techniques, how about Mega Purple? If necessity is the mother of intervention, then teinturier concentrate surely had to be devised to compensate for Nature’s lack. All that glitters is not gold, however. Glossiness is sheen deep; appearances are highly superficial.

No, colour does not have to be one hue or another. Wine colour can be one of many subtle shades on the spectrum and the result of farming and winemaking methods.

Take field blends. This is the traditional co-plantation of different grape varieties. These field plots are picked usually on the same day, with all the grapes subsequently fermented together. When white and red grapes are mixed, even if there is almost no maceration, the effect is that of a rosé. In terms of what we call it, it can be a mix of red, white and rosé. The grapes, skins and juice, are the components that make the wine what it is. The process is not an obviously extractive one, so the colour and wine itself will be necessarily light.

Colour does not have to be one hue or another. Wine colour can be one of many subtle shades on the spectrum and the result of farming and winemaking methods.

Calling a wine white is odd when one thinks about it. It is a catch-all term to describe any hue from green to rich beaten gold. Anything other than white, in fact. Rather than examining the objective clarity of the wine, one should instead focus on the quality of colour. A double-filtered wine has almost negative colour – it looks sterile. An unfiltered white, lees and barrel aged, is an entirely different proposition, holds the light in a different way, has depth, layers and textures of colour.

Ultimately, we should aim to be more colour-blind (or rather more colour sensitive) and seeing beyond the rigid classifications of colour. When perceiving a wine, colour can be more than a flat map – it is warp and weft, and textural coherence. It can have three dimensions and a pulse.