Here is a lexicon of definitions of key wine words. The definitions are not intended to be scientifically objective and, in many cases, will be somewhat simplistic. Some will describe the technical side of wine(s), others will examine the more abstract and aesthetic ideas behind wine.

Previously: A’s, B’s, C’s, D’s , E’s, F’s, G’s, H’s, I’s, J,K,Ls Ns, Os, Ps, Q&Rs (that’s right, this is so unalternative we’re even posting alphabetically…)

Saignée. French term for method of producing rosé wine by bleeding of the tanks after the wine has had limited contact with the red grape skins. This also has the effect of concentrating the flavours of the juice left inside the tank.

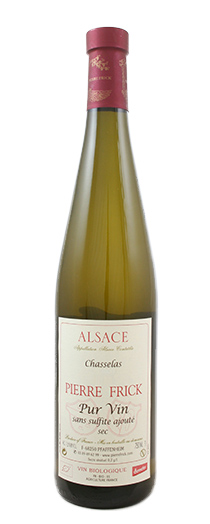

Sans soufre. Denoting that the wine has had no sulphur used in any part of the winemaking process. Sometimes sans soufre ajouté. May be used on the label is the total sulphur is less than 10 ppm. See sulphites.

Secondary aromas. Secondary aromas are associated with the smells that come about as a result of fermentation and not the grape or varietal itself (which are known as primary aromas), the most noticeable is when the wine undergoes oak barrel ageing. The reason for this is because the barrels have natural properties allow oxidation or create flavour compounds from contact with the wood. Secondary aromatics are complexing notes, associated with development on the palate. Sometimes confused or conflated with tertiary aromas which are the result of the age of the wine and are usually manifested in smells of earth, undergrowth, mushroom, truffle, tobacco, sherry…

Sediment. Solid matter consisting of deposits of dead yeast cells (lees), and bits of pulp and skin. In more commercial wines, the lees are filtered out at the earliest stages. Wines designed for long bottle ageing, on the other hand, frequently deposit crystals of tartrates, and in addition red wines deposit some pigmented tannins, as winemakers deliberately leave more tartrates and phenolics so that they are able to develop the aromatic compounds that constitute bouquet. Natural wines that are not filtered, often precipitate tartare crystals even in their youth, and some wines have even coarser material left in them. Ancestral styles of sparkling wine (e.g. colfondo Prosecco) have a thick layer of lees – almost a paste – at the bottom of the bottle – which can be shaken into the wine to make it cloudy and rich, or decanted so that it is cleaner and fruitier.

Sherry. Refers primarily to the wines made in the so-called “Sherry triangle” of Sanlucar, El Puerto de Santa Maria and Jerez, which range from dry fino and amontillado styles though oloroso to PX. Also used to styles of wine made elsewhere, either made in the same way or exhibiting same/similar characteristics to some of these wines. The wines from the “Sherry” region are predominantly fortified, although there are a few wines experimenting with non-fortified wines from the local grapes such as Palomino and Pedro Ximenez. A sherry-style wine normally refers either to one that has spent a lengthy period of time under the lees in a semi-oxidative environment and thus displays nutty secondary aromatics or one made in a similar solera fashion (eg a Marsala or Vernaccia) or an oxidative wine with rancio character.

Silky. Supple, smooth and flowing. Referring to red wines with light or low tannins, but with fruit combined with moderately lifted acidity and textural charm.

Smoky. An impression smelled and tasted on certain wines as a secondary aromatic or flavour. Smoky smells can, of course, come from the barrels themselves and those aromas will issue from the nature of the wood and the degree of toasting used to season it. Highly toasted barrels of new wood can confer overt smoky aromatics to the wine. Some grape varieties, such as Syrah, present a smoky reduction, and indeed reduction is perceived on the palate as smoky minerality (for example, gun flint).

Smooth. Like silky, an adjective applied to wine in which neither tannin nor acidity are dominant features.

Soif, Vin de. A wine to drink to assuage one’s thirst. Easy-drinking, very fruity and uncomplicated. Other synonyms for soif wine include glou or glouglou wine; thirst wine; smashable wine; juice. Many soif wines, usually red, are made by carbonic maceration. Soif wines are closely associated with a particular style of natural red wine made throughout the world, one that accentuates the simply purity of fruit rather than one that makes a statement about terroir.

Solera. Solera is a process for ageing wine and other spirits and vinegars, by fractional blending in such a way that the finished product is a mixture of ages, with the average age gradually increasing as the process continues over many years. The reason behind this is to create a house style. Solera means “on the ground” in Spanish, and it refers to the lower level of the set of barrels or other containers used in the process; the liquid is traditionally transferred from barrel to barrel, top to bottom, the oldest mixtures being in the barrel right “on the ground”, although the containers in today’s process are not necessarily stacked physically in the way that this implies but merely carefully labelled. In the solera process, a succession of containers are filled with the product over a series of equal aging intervals (usually a year). A group of one or more containers, called scales or criaderas (‘nurseries’), are filled for each interval. At the end of the interval after the last scale is filled, the oldest scale in the solera is tapped for part of its content, which is bottled. Then that scale is refilled from the next oldest scale, and that one in succession from the second-oldest, down to the youngest scale, which is refilled with new product. This procedure is repeated at the end of each aging interval. The transferred product mixes with the older product in the next barrel. And so forth. Solera, as a term, is now applied to other areas of winemaking, especially in the cases where vintages of wine are blended, or even the lees of different vintages are added to the wines.

Sommelier. A person who offers advice to customers in a restaurant on the wine list, who brings the wine to the table and serves it. The person who buys wines for restaurants and puts together the wine list. Nowadays, used to describe any person who advises on wines and perceived as a more skilled and multi-functional position than a “wine waiter.” Many sommeliers pass exams, travel extensively and even have experience of making wine and head sommeliers are an integral part of the restaurant management hierarchy.

Spicy. A wine with aromas and flavours reminiscent of various spices such as black pepper and cinnamon. While this can be a characteristic of the grape varietal – for example, the black pepper notes of Syrah, the white pepper rotundone aromas and flavours of Pineau d’Aunis – many spicy notes are imparted from oak influence, be it broader notes of vanilla and cinnamon to more fine-grained ground spice. On white wines, lees-ageing gives flavours of white and yellow spice, from dried ginger and cumin to more sotolon-related flor-generated aromas of fenugreek and curry powder.

Spoofy. Applied to pretentious or overwrought wines wherein the oenologist is striving by means of various interventionist tropes to create a wine that is superficially impressive. Spoofy wines are dark to the point of impenetrable, rich, powerful, sweet, and full of extract. Often, they are from grapes that have been allowed long hang time to acquire greater ripeness to give the material for the winemaker build his/her architecture on.

Steely. A wine-tasting term used to describe an aspect of certain white wines. Wines made from grapes that grow on hard chalk or other hard rocky soils sometimes exhibit an intensely metallic quality amplified by low ph/high acidity. In the mouth, this presents as a tensile, linear impression, also where the wine appears reserved, “coiled” and austere. It is a positive descriptor linked with the idea of sophisticated minerality and the attribute of backbone.

Sticky. Colloquial expression for sweet fortified wines, particular liqueur muscats, ports, px etc, wines that are almost viscous in texture.

Stony. Any aroma or flavour in wine that once perceived, reminds one of rocks and stones. These perceptions are associative, of course, but just as mineral water contains mineral salts, so it seems that wine can volatilise mineral compounds which make up the very soil and subsoil in the vineyard. Stoniness in a tasting note is usually a reflection that the wine is bone-dry, has high or focussed acidity and leaves the impression of stones or shells on the aftertaste. One may smell and taste notes of water over stone/petrichor on white wines such as Chablis, Riesling or Chenin on particular soils. Limestone, granite, slate all imbue wines with a distinctive minerality. Red wines too can be impressed with the flavour of stones. It should be said that organic farming is important, because it encourages vines to develop deep and complex root systems which pick up mineral nutrients.

Structure. Structured. The nature of the framework of the wine. In simplistic terms, wine is built on pillars of fruit extract, tannin, acidity and alcohol, to which I would add minerality as a further buttressing element. A good/solid structure is when each of these pillars support the wine more or less equally or in a way which is balanced. A structured wine is one that possesses the foundations to age for considerable period of time. What gives a wine structure is the material of the grapes primarily, but also the nature of the winemaking (extraction of colour, tannins from the grapes), long ferments, long maturation on the lees in barrels and also ageing in bottle.

Sulphur/sulphites. Winemakers may add sulphur at one – or many – junctures during the vinification process, such as at the point of harvest, at the end of the fermentation, on each occasion that the wine is racked, and before bottling. It should be noted that sulphur dioxide is also created to a greater or lesser extent as a natural by-product of winemaking. Whereas most of the sulphur is absorbed into the wine; that amount of sulphur which is unbound, is called free sulphur. The sulphites content of a wine is measured in parts-per-million (by EU law, 210 ppm for white wines and 150 ppm for red wines are the allowable upper limits). A wine does not have to carry the label “contains sulphites” if the total SO2 is measured at below 10 parts per million. Sulphur is used as a disinfectant, to prevent bacterial spoilage, to protect against oxidation and to inhibit the malolactic, and even to focus certain reductive flavours and textures in the final wine. For all that it is regarded as an everyday part of winemaking it can be overused, be highly apparent on the palate, bruise the wine’s fruit and obfuscate the transparency of the flavours. Many vigneron(nes) now eschew the use of sulphur during the winemaking but may add (if required) a small quantity before the wine is bottled. Others choose not to add any sulphur whatsoever believing that only then may the wine attain its purest expression, that the wine must rise or fall on the quality of the naked juice alone.

The issue of sulphites in wine has become an inexhaustible subject for conversation both within and outside the natural wine world. The reality is that most vignerons take a position on adding sulphur according to the needs of the wine in question, rather than adhere intransigently to the zero-added standpoint.

Supple. Like smooth, a descriptor denoting a harmonious wine that possesses a velvety texture. Supple tannins are normally soft and rounded and certain grape varieties such Merlot tend to produce supple wines.

Sur Lie. The lees are the spent yeast cells from the fermentation process. These yeasts still have a job to do for many vignerons; for they can nourish the wine further, provide it with body and texture and protect against oxidation (reduction under the lees). When the lees have fallen to the bottom of the fermentation vessel, they can be agitated back into the wine by means of stirring (batonnage). When the wine is racked into a clean container or barrel, the gross lees may be left behind, but the fine lees (in suspension in the wine) will go with the wine. Wines such as Muscadet and Champagne are famously left on the lees to build more flavour and texture, but many quality wines rely on lees-contact for their structure and their personality.