Read Chapter One Parts One, Two and Three and Chapter Two Parts One, Two and Three here.

Each friend represents a world in us, a world possibly not born until they arrive, and it is only by this meeting that a new world is born.

–Anais Nin, The Diary of Anaïs Nin, Vol. 1: 1931-1934

It is a cliché to talk about one’s journey, as if there is single story arc which reaches an inevitable conclusion. In reality, life comprises lots of chance encounters and happy collisions that push you one way and pull you another. The most rewarding aspect of working for a wine company is that it brings you into contact with some truly remarkable people with whom you forge long-standing friendships that go beyond the quotidian transactional business relationship.

We work with over four hundred and fifty growers from twenty-two countries. All are special to us, but some are family.

The Guibert Family and the Magic of Gassac

…Clarissa was passing me the bottle–a 1987 Daumas Gassac. This was the moment, this was the pinprick on the time map. —Ian McEwan, Enduring Love

I first became aware of the wines of Mas de Daumas Gassac in the late-1980s when I was working in a small family restaurant in South Kensington. I didn’t know the full back story of the domaine then, but the name of the wine itself had almost mystical (and magisterial) connotations. Bear in mind that this was the time of plonk de Midi, those cheap, rough wines made by co-ops or growers who believed that the bigger the yield the better the wine. Bring on the 300 hl/ha Aramon, by your leave! Gassac was the wine that helped put the south of France on the serious wine atlas. It was anointed as the Haut-Brion of the Hérault, the Ausone of Aniane and the Lafite of the Languedoc (I made two of those up) and other alliterative claret-y comparisons. Critically acclaimed the wine may have been, but the foundations of this unique estate were truly based on fabulous terroir and a clear-eyed determination to make the best possible wines without going down the path of spoofiness*.

We work with over four hundred and fifty growers from twenty-two countries. All are special to us, but some are family.

*The term spoofulated or spoofy is occasionally used to describe wines that are made in an overly slick, international, even meretricious style.

We are not making Coca-Cola here. —Samuel Guibert

No, they are not making coca cola. One could write a book about this domaine. However, the book of the Gassac story and the wine has already been most ably penned by Alastair Mackenzie, whereas the older vintages have been scrupulously chronicled by the redoubtable Michael Broadbent in his Vintage Wine. Daumas Gassac, a long-standing Broadbent favourite, is one of only wine estates to merit a special chapter to itself (along with Chateau Musar and Vega Sicilia) in that particular tome.

The story of Mas de Daumas Gassac is one of vision, enterprise, passion and pride. When the Guiberts first purchased their farm (the mas) in the charming Gassac valley they little realised that they had a special micro-climate which would give them the potential to make great wines. A visiting professor from Bordeaux, one Henri Enjalbert, identified a particular red soil that was common to certain great estates in the Médoc and Grand Cru Burgundies. Under the thick garrigue scrub and shrubs covering the Arboussas hills, he found some 40 hectares of perfectly-drained soil, poor in humus and vegetable matter, rich in mineral oxide (iron, copper, gold etc). Formed from deposits carried in by the winds during the Riss, Mindel and Guntz glacial periods (ranging from 180,000–400,000 years ago) the terroir provided (and provides) the three elements necessary for a potential Grand Cru: deep soil ensuring the vines’ roots delve deep to seek nourishment; the excellent drainage ensuring the vines’ roots are unaffected by humidity; poor soil meaning that vines have to struggle to survive, an effort which creates exceptionally fine aromas. Rock, scrub and tree clearing began in 1971 and the first vines, principally Cabernet Sauvignon, were planted on the 1.6ha plot.

Mineral-rich soil is only one element in the Gassac cocktail. You only have to stand in the vineyards to engage with the subtleties of the micro-climate. The hill is thick with garrigue; strong warm scents of wild herbs imprint themselves in the air; the quality of light is fantastic. The vines are planted in small clearings, magical glades hidden in the dense, forest-like garrigue. The complexity of Daumas Gassac wines derives heavily from these scents of myriad Mediterranean wild plants and herbs: bay, thyme, rosemary, lavender, laburnum, fennel, wild mint, lentisque, strawberry trees… It’s all part of the ‘terroir’ effect, that combination of soil, climate and environment that sets one wine apart from another, sadly an effect that is lost in modern monoculture, where huge areas are cleared of all vegetation except vines. At nightfall, the cold air from the Larzac plateau (850 metres) floods into the Gassac valley, with the result that, even in the height of summer, the vineyards benefit from cool nights and moderate daytime temperatures. The northern facing vineyards accentuate the beneficial effect of this cool micro-climate by ensuring they are exposed to less direct sunshine during the hot summers. The micro-climate also means that the vines flower some three weeks later than the Languedoc average which in turn is significant factor in creating the outstanding complexity and finesse of the red wines, most especially the splendidly fine balance of the great vintages’ alcohol-polyphenol-acid content.

You only have to stand in the vineyards to engage with the subtleties of the micro-climate. The hill is thick with garrigue; strong warm scents of wild herbs imprint themselves in the air; the quality of light is fantastic.

Yes, the Gassac valley is an energising place, full of beauty, and reminds one that it is the sacred role of the vigneron to coax the beauty from such an environment into the bottle.

The domaine cellars have been created in the foundations of a Gallo-Roman mill; they now house around Merrain-oak Bordeaux barrels; one in seven of which is replaced each year. There are two cold water springs under the cellar’s floor, nature’s own air conditioning system, which slows the alcohol fermentation down to between 8 – 10 days. This slow process means the complex flavours have time to develop, something that doesn’t happen with modern high-tech fermentation. You cannot talk about Gassac without mentioning Emile Peynaud who effectively came out of retirement in 1978 to mentor the Guiberts in their early wine-making endeavours.

The wines do not lie; they have natural elegance and a purity that marks them apart. Each vintage is truly a testament to a wine-growing season; one tastes the terroir rather than the technique.

One of the first things that Eric said to me when I joined Les Caves is that “we follow the grower”. You see, or rather sense, the potential, when you talk to a person, share a bottle of wine with them, listen to what they have to say about wine, and also witness how they interact with their terroir, how deeply they understand what is beneath their feet and what is in the air. Some growers have this elemental and intimate connection to place and are pledged to channel its energy. With the Guiberts you sense that they are in love with their Gassac valley and rightly proud of the wines that it yields.

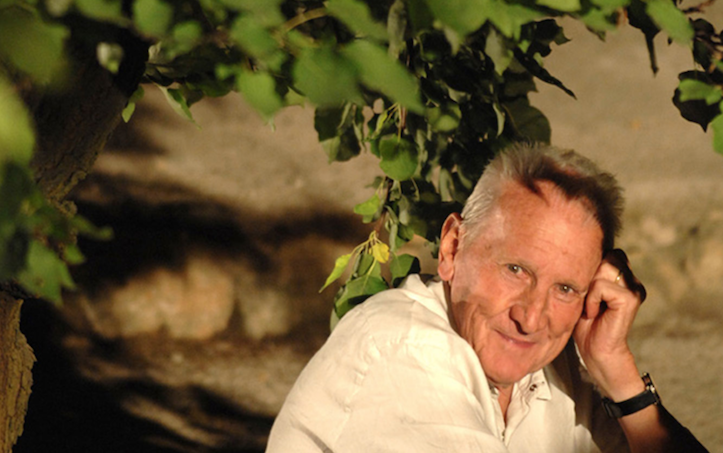

A Tribute to Aimé

The last time I saw Aimé Guibert was on a sommelier trip to Mas de Daumas Gassac several years ago. Having been shown around the beautiful and unique vineyards, we repaired to the winery next to the tumbling mill stream. Aimé suddenly appeared from a side door, fixed us all with a smile, his eyes twinkling mischievously: “Australian wine?” he mused. “It is not poison!”

Aimé was all about rejecting conformity. “Rejet de clones” is indeed one of the Gassac maxims. Presented with a unique terroir identified by Professor Henri Enjalbert in the early 70s his family planted vines on slopes in forest clearings and proceeded to make world class wine. What wine with no appellation is considered by the expert and wine connaisseurs as “The only Grand Cru of the Midi” (Hugh Johnson), “A Lafite in Languedoc” (Gault & Millau); “One of the 10 best wines in the world” (Michael Broadbent or simply “Exceptional” (Robert Parker). But this was more than an iconic, garagiste wine. The Mas de Daumas Gassac Rouge was truly about the terroir and the vineyard.

Aimé Guibert became one of the truly important figures in French wine, associated with wines that could be spoken in the same breath as those from the classic regions of Bordeaux and Burgundy. He could also be controversial and featured prominently in Jonathan Nossiter’s Mondovino (2004), a documentary about globalisation and conformity in the world of wine. “Le vin est mort” Aimé intoned mournfully as he climbed slowly to the top of the hill of his favourite vineyard. Fortunately, artisan “vin” has survived the march of globalisation, and the market desire for homogeneity can never stifle the expression of individuality. Aimé’s legacy is in the safe hands of his sons who run the estate with equal passion and love for their patrimony.

Some growers have this elemental and intimate connection to place and are pledged to channel its energy.

When you visit Gassac you will see other signs of his legacy. Diversity is the key to the Gassac vineyards. With 40 different grape varieties planted in the valley, the vineyards are like museums of rare and uncloned vines from around the world: Israel, Portugal, Switzerland, Armenia, Madeira, etc. The estate was farmed in a traditional and natural way long before the Guibert family established the Grand Crus vineyards of Gassac. They were the amongst the very first estate in the Languedoc to adopt full organic farming and can honestly say that the Gassac estate has never seen any chemicals. The family commitment to preserving and protecting the land is unparalleled. After all, it’s where they eat, drink and live!

To meet Aimé Guibert was to be part of his extended family. He was a committed Anglophile (and loved Ireland also) and the UK response to him and his wines was equally warm and loyal. Many many people bought the Mas de Daumas Gassac wines on release in their famous en primeur offers. Despite the increasing reputation of the wines the prices were always very fair; unlike Bordeaux the prices never tracked the vintage. We were fortunate enough to be appointed UK agents for Mas de Daumas Gassac many years ago and have built a relationship of trust and mutual respect with the family. It has been a privilege to work with Aimé’s estate.

I remember once standing behind a table at the Decanter World Wine Fair in London a few years with his son, Samuel, in a room surrounded by the great and the good of Burgundy and Bordeaux. Our table was by far the busiest in the room–the knowledge and the appreciation of the customers for the wines was incredible. The commercial and reputational success of Gassac will stand as a monument to Aimé’s achievement; the deep love of his family and friends is a further testament to how profoundly he will be missed.

In the movie version of Enduring Love, starring Daniel Craig and Samantha Morton, the bottle of 87 Gassac is replaced by a bottle of Krug–a further example of cinema dumbing down the source material.

The Mas de Daumas Gassac have been vin de pays since their inception. Which begs a question.

A Digression on Appellation: What’s in a Name?

The notion of appellation was originally a charter, often a royal seal of approval. Appellation or “naming the wine” gave it an official legitimacy. The word has since – in many people’s views – moved away from expressing the need to protect regional identity and promoting authenticity by supporting good practice towards more negative associations such as died-in-the-wool protectionism, restrictive and inflexible practice and bureaucratic authoritarianism.

Appellation was never intended to stamp a homogenous identity on wine and winegrowers. It was meant to encourage them to improve their working practices, and to inform consumers as to how such methods affect the way an appellation speaks though its wines. Typicity and diversity are not mutually exclusive; within each appellation there are myriad terroirs and ways of representing them. Wine is a soft interpreter of the grape variety, the microclimate (the aspect, the soil, the vegetation, the sunlight, the heat and so forth) not to mention the technique in the winery – there are as many wines as there are variables in a given year. Diversity is therefore, by definition, a fact of nature. But a vigneron looking to preserve the subtlety and unique character of a specific place, to capture the essence of terroir, will never try to modify or homogenise his or her wine by driving out nature with a pitchfork.

Typicity and terroir mean simply this: that wine duly reflects where it comes from and changes according to the unique variables of each vintage, but the wine has an inherent identity, a singularity that tells us that it is a natural product from a “specific” place.

It is interesting finally to note that the quality charters of La Renaissance des Appellations and Slow Food France are based on philosophical and ethical convictions as to what constitutes terroir and good farming practice and are not legal frameworks. This highlights the problem with so many things in our world: people are bluntly told they can’t do such-and-such when it should be explained instead why it would be a morally good idea for them to pursue a particular course of action.

Ideally, and from a consumer’s viewpoint, appellation should be inextricably connected to quality. Quality can be determined by pinpointing origin of product and methodology or farming practice – these are objective measures – in conjunction with the subjective evaluation of tasting panels.

A vigneron looking to preserve the subtlety and unique character of a specific place, to capture the essence of terroir, will never try to modify or homogenise his or her wine by driving out nature with a pitchfork.

Mas de Daumas Gassac has become its own de-facto appellation, not simply reflecting the terroir of Aniane and the wider Languedoc, but of the Gassac Valley with its unique micro-climate.

Rock (R’Oc) Music

Tommy’s got his six acres in ‘Oc

Now he’s ploughing all the garrigue

And the rock-so tough, it’s tough

Gina dreams of making some wine

When the harvest is tiny

Tommy whispers baby it’s fine

We’ve got to hold on to what we’ve got

‘Cause it doesn’t make a difference

If we make it or not

We can sell to the co-op and that’s enough

To survive–even if it’s a bit tough

Whooah, it’s hard to bear

Zero wine is so unfair

Take my hand and we’ll make it-I swear

Livin’ on a prayer

Solo (project)…

–Buono Giovese

Clos du Gravillas: from the cradle of Carignan to the gravel-voiced Kentuckian

There comes a time in life when one begins to prize young wine. On a Southern shore there is a string of round, wicker-covered demijohns always kept in store for me. One grape harvest fills them to the brim, then the next grape harvest, finding them empty once more, in its turn fills them up again… do not disdain these wines because they give such quick returns: they are clear, dry, various, they flow easily from the throat to the kidneys and scarcely pause a moment there. Even when it is of a warmer constitution, down there, if the day is a really hot one, we think nothing of drinking down a good pint of this particular wine, for it refreshes you and leaves a double taste behind, of muscat and cedarwood.

–Colette, Earliest Wine Memories

Gravillas possesses a gentle energy. It’s the magic of terroir and those white rocks and a family that has settled into an environment. Growers who are in a happy place are themselves liberated to make “free wines.”

At Clos du Gravillas there 15 different grape varieties including some ancient Languedocian autochthones, Carignan-central in the home of Muscat, brilliant stony terroir, a Kentucky-Narbonne marriage with a flair for enjoyment. Witty resonant labels, off-beat-but-true-to-their-roots styles, organically-farmed wines for smashing, others destined for sunshine food and slow cooked meat. The people are funny, affectionate, friendly. Familial.

Nicole Bojanowski grew up in Narbonne, with her “accent du SUD”, her laugh, her contagious enthusiasm. Husband, John, came to St Jean de Minervois from much farther west, the land where horses drink Kentucky bourbon. In 1996, the sud French girl convinced her southern-bred beau that the white rocks of St Jean were the most beautiful rocks in the world.

John Bojanowski has been a sunshine constant in the life of Les Caves.

It was some choice, giving up the pleasures of the whole wide world for an arid rocky plateau and a hamlet of 49 souls. But it was the choice of a terroir, white phonolithic gravel and it was a choice that’s made so much difference.

The rocky land immediately brought to mind thoughts of moonscapes. The wines might be considered lunar in their minerality, some might even suggest lunatic…but always delicious.

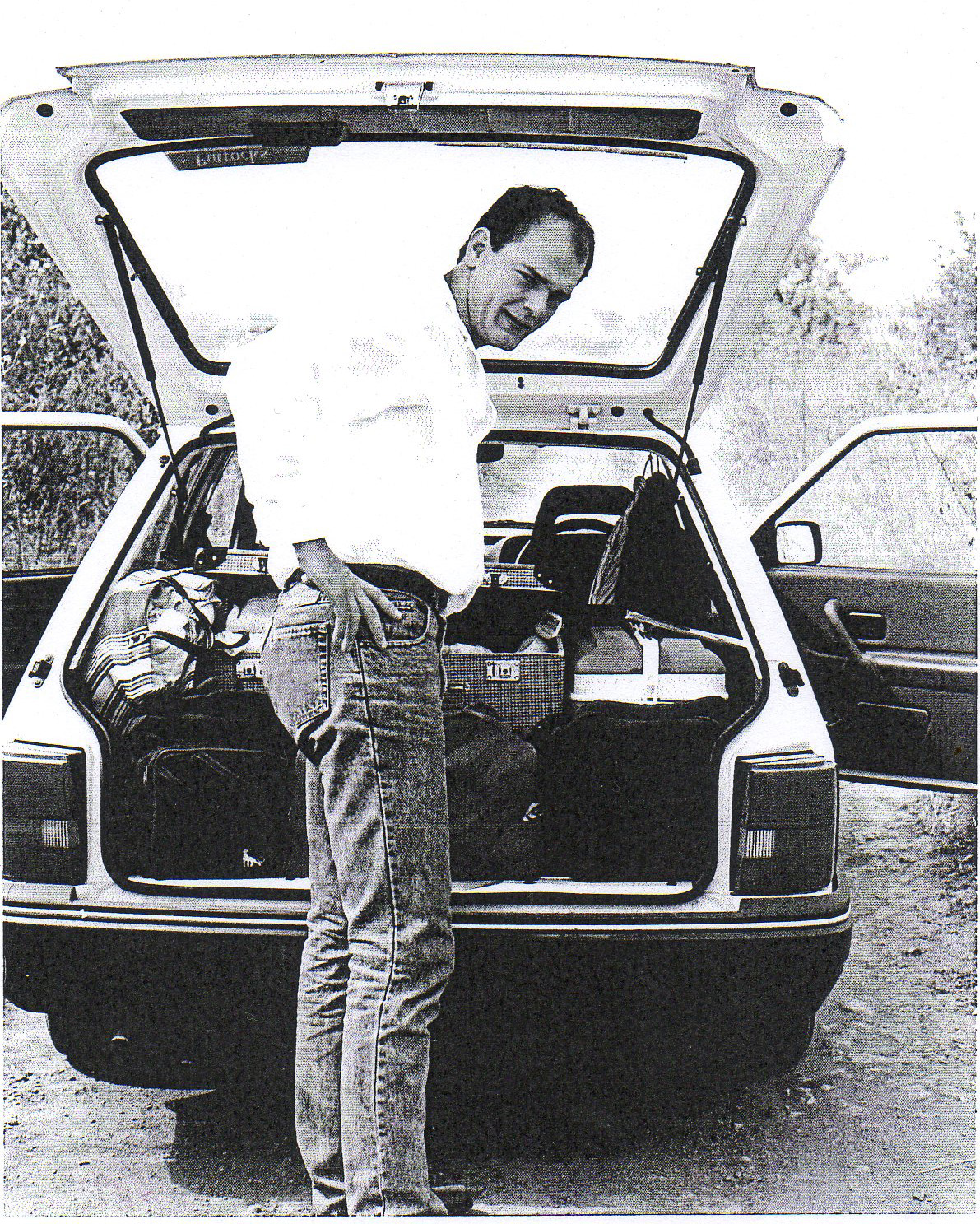

The back of beyond. When I visited Nicole and John a few years ago I took my wife and baby son. The start of the journey was not auspicious as my wife had never driven an automatic before, and we spent the first half an hour careering around the airport car park in Perpignan so that she could familiarise herself with the navigational controls (as they say in Star Trek). After some hapless map-reading of my part, which took us into tiny non-scenic cul-de-sacs and once into a recycling plant, and with car windows steamed blue with cussing, we managed to find the turn-off into the back country. The wrong turn-off, as it happened. The road was circuitous, to put it mildly, winding around every garrigue shrub and tree. After about half an hour of meandering in this wilderness we passed by a couple of houses and then began to descend back into the sea of garrigue in the direction of Saint-Chinian. We were truly, madly, deeply lost. I phoned John in tears and discovered that those couple of houses we passed by, were, in fact, downtown St-Jean-de-Minervois, the village that gives its name to an entire appellation. Suitably fortified, like the local Muscat, with this geographical knowledge, we returned to where a solitary tall figure with defiantly curly hair was waiting our arrival.

The cute hamlet St. Jean de Minervois (population mid 40s and rising, or falling, as the case may be), lies in an area renowned for its delicious, grapey fortified Muscats. Gravillas means “gravels” in the local patois, and the white limestone gravel plateau that the Clos du Gravillas is located on, has been used to grow grapes for hundreds, if not thousands, of years. The micro-climate assists the process of making great wines. Situated about 300 metres above sea level on slopes beneath the Montagne Noire, the vineyards catch the cool evening breezes, allowing the grapes to retain more of their acidity. The high summer temperatures of this region during the day add the necessary alcohol to balance the acidity, creating the structural depth and maximum grape ripeness required to make excellent wine.

Once you’ve got wonderful grapes (if it’s not good enough to eat you throw it on the ground is the Gravillas maxim), you concentrate on bringing out their true character in the wines – you find your style (or it finds you). This winery is very small, low tech and tactile to the limit—the crusher is several pairs of rubber boots. Keepin’ it simple.

Nicole and John seek a balance a balance between rich and refreshing–a bit of chalkiness and a deep pure dark sappy fruit in the reds, and in the whites an expression more mineral and floral than fruity.

They began their venture in 1996 by planting Syrah, Cabernet and Mourvèdre, and in 1999 started making wine in earnest, when they discovered 2.5 ha of Carignan planted between 1911 and 1970, and a small parcel of old Grenache Gris vines. These were to form the basis of their cuvées called Lo Vielh and L’Inattendu respectively. Since then they have acquired a veritable mixed portfolio of grapes featuring no fewer than fifteen varieties. We’re looking forward to the Languedoc’s premium Chateaneuf-style field blend. Plus one. Or not!

Comprising old-vine Grenache Gris with some Grenache Blanc and Macabeu, L’Inattendu, or “The Unexpected,” a dry Catalan-style Minervois Blanc, was once destined to be a kind of “rosé manqué” in that the vinification is similar to that of a rosé, but the result was a nutty white wine. Old vines, tiny yields, natural vinification, and twelve months on the lees relaxing in Allier oak give birth to a wine that is rich and resinous, with a good balance of green apple and reductive mineral flavours, and an elegant mouth feel. Early vintages revealed oxidative notes and distinct old woody quality that either charmed or puzzled, but now the wine unites richness with incisiveness. There is lovely custard apple fruit allied to dried apricot, vanilla, garrigue notes of herbs and all sorts of ginger and white pepper on the finish. The warmth of the alcohol does not detract but rounds out the mouth; it is a textural wine with the reverberating minerality of terroir from those hot stones. We love to see this progression–follow the grower indeed.

And time for all the works and days of hands…

Time for you and time for me,

And time yet for a hundred indecisions,

And for a hundred visions and revisions

Before the bottling of a wine sur lie’

—With apologies to TS Eliot

Their charmingly-named Emmenez-Moi au Bout du Terret is made with Terret Bourret, local to the Hérault and is bright and playful. Fermentation and ageing take place in Stockinger Austrian barrels. “To get the best out of this old and unevenly ripening grape, we make three passes through each of the three vineyard blocks. First week and third week of September, we tell the pickers ‘only the pink bunches’. A week later we get the rest.”

These guys invest in “les mals-aimés”, the historical local-yokel critically-disregarded grapes. An interesting counterpoint to Gassac with their pan-Mediterranean archive of oddments, Gravillas have accumulated tiny parcels above-mentioned Terret Bourret, some vines of ancient Aramon, Counoise and, of course, are Carignan hub city.

Carignan may perform solo, but is equally good in an orchestra of varieties. It lends an earthy minerality to the ensemble and with age stands on its gnarled feet. Sous Les Cailloux des Grillons, a wine that proves that it can be definitely cricket and crickety-boo (and refers to the ubiquitous crickets/grillons that lurk under the gravels and the night sky), is a delicious, savoury dark-and-red-fruit-filled blend of Carignan, partnered by Syrah, Cabernet Sauvignon, Mourvèdre, Counoise, Grenache Noir and Terret Gris. This wine always puts a smile on my face and is as friendly as the welcome from Nicole and John. Sur La Lune was originally created to be a Carignan in a different style to Lo Vielh, but has metamorphosed over the years into a Syrah and Carignan blend aged in tank. The nose is pure cassis with the element of menthol and eucalyptus, the palate has notes of bitter fruits and pepper. Its name is a reference to the lunar landscape of Cazelles. This wine is perfect with lamb tagine or a roast vegetable couscous or stuffed peppers.

These guys invest in the historical local-yokel critically-disregarded grapes.

Lo Vielh, aka the old one, comes from a couple of hectares of vieux Carignan; the oldest vines should have received their telegram from the Queen already. By pigeon post. Aged in 400-litre Allier oak barrels, the wine combines power and purity, the fruit is dark and velvety and is truly delicious. Virtually no sulphur is used (the fermentation lasts around six months) and the wine seems to have soaked up a century’s worth of minerals. This is wine that sits up, barks and makes you take notice. One to stick your spurtle into. The fruit is blueberry-ripe with liquorice swirls and hint of tobacco. There are also discernible meaty undertones. What wouldn’t you eat with this? A steak cooked in the embers of a fire in a wee Languedocian restaurant (there’s one in St Jean de Minervois), a shoulder of pork slow roasted in the oven, or breast of duck with griottine cherries – the choice is endless…

Muscat is what Saint-Jean de Minervois is renowned for. Douce Providence is as delightful as its name suggests being floral and fruity with whiffs of orange flower and honeysuckle combining with flavours of sweet pink grapefruit and mandarin. Sweet providence indeed. The finish has such a refreshing tang that you should drink à la mode as an aperitif, but it would take equally kindly to strawberries and fruit pastries. Muscat de St Jean de Minervois is cited in nationally syndicated US press article (Gannett Indianapolis Star et.al.) as being 2nd best sweet wine in a food/wine pairing with Twinkies and other industrially produced snack cakes. John is quoted as being “delighted… and that it is about time our Muscat gets the recognition it deserves. This is going to boost us to USA nationally-recognized status. Just wait until they try our new Dark Side 99-year-old vines Carignan with Tacos!”

John is a Carignan evangelist (is there any other kind) and Clos du Gravillas is at the forefront of a website devoted to reviving the reputation of this grape variety. If you’re jaded by the Merlot world (and we are, we are) and looking for a “vin d’ici” then Carignan is the one for you. We’ve chugged it in Chile, argle-gargled it in Argentina, slurped it in Spain and lapped it in the Languedoc-Roussillon and we can say that the wines from these rugged vines, in whatever country, deliver great terroir flavour, usually at a fantastic value.

John Bojanowski has been a sunshine constant in the life of Les Caves. He’s been to every fair and tasting, supported us at the Real Wine Fair, makes cracking, consistent wines without fanfare, is not afraid to experiment either and have fun. He and Nicole always receive us and our customers with genial hospitality.

The Bourgeois Family: Expressing Terroir in Sancerre

Urbane Arnaud Bourgeois, of Henri Bourgeois, has been a friend of Les Caves de Pyrène since the early days. With his brothers he is the inheritor of one of the great domaines in Sancerre and Pouilly-Fumé, one that has acquired an acclaimed reputation for its precise wines over the last few decades.

The story of the English Chavs in Chavignol

Our group of reps travelled en mini-masse to their headquarters in Sancerre in 2009.

Three cars departed from Calais at the same time, and one would have thought it would be nothing other than a straightforward trip to Sancerre. The Bourgeois winery is a mere two hours by road from Paris, so proclaims their website. This was not factoring in that a butterfly flapping its wings in New Mexico would cause a storm of uncertainty in Northern France that blew us totally off-course. Carlo, The Driver, had surrendered his free will, and become the slave to the Man (or the sat-nat), which itself was fulfilling its own destiny (but not its destination) in a version of Stephen Hawking’s predicted rogue robot rebellion, by behaving erratically and steering us towards the maelstrom of central Paris, when we wanted to give that whole city and its environs, the widest of wide berths.

Hours and hours later via multiple twists and turns, it was a frazzled band of Cavistes that heaved into the small town of Sancerre where we reconvened with our colleagues, who had been glugging gin and tonics at the bar for ages and were noticeably marinated.

The siren voice of said sat nav lured us off the motorway, had us zig-zagging the suburbs through a maze of alleys and finally deposited us in a parking lot behind a housing estate. Off the beaten sat-nav. Sancerre seemed a long way away (and it was now) as we drove around in ever-decreasing circles, vainly trying to escape the closed network of streets. Eventually, more through luck than judgement and accompanied by a good deal of helpless laughter mixed with primal screaming, and with the sat nat in complete nervous breakdown mode, we managed to discover the route back to the motorway. Unfortunately, now we were now heading north, back to Calais. Not that we weren’t heading anywhere, because the rush hour traffic was completely dammed.

Hours and hours later, (seven after we started in Calais), via multiple twists and turns, it was a frazzled band of Cavistes that heaved into the small town of Sancerre and parked by the Hotel Panorama, where we reconvened with our colleagues, who had been glugging gin and tonics at the bar for ages and were noticeably marinated. The hotel lounge did boast stunning views over the Loire valley. We gawped appreciatively. Maybe this was worth the detour. Or maybe not. Our fellow-travellers affected to be blasé as if they had seen enough of the Loire already to be sated.

The views from the bedrooms are apparently even more amazing, I vouchsafed to my colleagues as we checked in. (I’d read the brochure and seen the pictures of the magnificent panoramic views that the hotel was advertising.)

The manager gave a thin-lipped smile. Yours aren’t. You’re all overlooking the carpark.

There wasn’t any time to admire the unrivalled views of the carpark from our rooms, before our dinner appointment at…

The Hôtel Restaurant de la Côte des Monts Damnés

More than a winery restaurant this is the brainchild of chef Jean-Marc Bourgeois, who had absorbed the influence of his native Chavignol, and having added some classical training at Taillevent, was now reinterpreting the culinary heritage of his region.

After our stressful circumnavigations, it was lovely to be ensconced in a comfortable restaurant with a great foodie reputation.

We settled back contentedly. The Sauvignon, glinting in our glasses, beckoned. The enticing aromas of Sancerre, flowering currant buds, chalk and cut lime, the crackle of sharp citrus fruit on the tongue.

Finally, the moment we were waiting for.

In the tiny hamlet of Chavignol, supping the very best fossil-licked Sancerre, harvested from the very hill we were sitting beneath, the preconditions for gastronomic epiphany, only requiring the addition of a sliver of crottin de Chavignol to make the experience complete. This was going to be our Monty Python cheese sketch moment, only with lashings of cheese. In fact, nothing like the cheese sketch. I was drooling in anticipation of tasting chalky crumbliness of the local goat’s cheese cut by the crunchy curranty tang of the best Sauvignon. When in Chavignol, get your goat out!

The cheese arrived.

Wayne: There it is—Excalibur. [“kneels” in respect]

Cassandra: Wow. ’64 Fender Stratocaster in classic white with triple single coil pickups and a whammy bar.

Wayne: Pre-CBS Fender corporate buy-out.

Cassandra: I’d raise the bridge, file down the nut, and take the buzz out of the low “E.”

Wayne: God, I love this woman. [reacts at Garth who just walked into some chimes] Hi, Garth. Where’s the clerk? I know. I’ll use the “May I help you” riff. [picks up another guitar and does a heavy metal riff]

Attendant: May I help you?

Wayne: [puts down guitar] Yes, my good man. I’d like to look at this Fender Stratocaster, please.

Attendant: Oh really?

Wayne: Yes.

Attendant: Again?

Wayne: Yes.

Attendant: [opens plastic case and gives Stratocaster to Wayne] Careful.

[Wayne starts strumming some chords but the attendant knows the song. He stops Wayne and points him and Cassandra to a “NO STAIRWAY TO HEAVEN” sign]

Wayne: [to camera] No Stairway. Denied!

…It was a Camembert!

Denied!

I was sitting opposite Gideon. I saw his jaw drop at least three feet. Where’s the cr…crot…crottin…

In parts of France they know how to order contempt with a chaser of disdain.

After our crottin-bathetic repast, we returned to Sancerre, and played pool for three hours in the local bar. The hotel had given us a code to enter on the electronic keypad lock after midnight. That code didn’t work. Somehow, we managed to gain entry and went to our respective rooms (on the third floor). None of the lighting worked in the hallway. Nor in the rooms themselves. I turned on everything just to be certain. Next door, I could hear David and Thierry cursing and crashing into furniture. And coming from the bowels of the hotel was a strong smell of cigar and a very distinct whiff of sewage.

Apparently, there is no word for hospitalité in French.

Guard: ‘Allo, daffy English kniggets and Monsieur Arthur-King, who has the brain of a duck, you know! So, we French fellows out-wit you a second time!

Arthur: How dare you profane this place with your presence!? I command you, in the name of the Knights of Camelot, to open the doors of this sacred castle, to which God himself has guided us!

Guard: How you English say, I one more time-a unclog my nose in your direction, sons of a window-dresser! So, you think you could out-clever us French folk with your silly knees-bent running about in dancing behaviour! I wave my private parts at your aunties, you cheesy lot of second-hand electric donkey bottom biters.

Arthur: In the name of the Lord, we demand entrance to this sacred castle!

Guard: No chance, English bedwetting types. I burst my pimples at you and call your door opening request a silly thing. You tiny-brained wipers of other people’s bottoms!

More than slightly the worse for wear and having barked my shins several times in the dark I lay down on my bed.

What seemed about half an hour all the lights in the room came jamming on and the TV which I had turned on to see if it was working came on full blast.

Downstairs during breakfast we were recounting our various mishaps in the dark. I surmised out loud that the hotel had had a power cut during the night. The manager who was lurking within earshot, pursed his lips in a superior grin.

Oh, no, it was just your floor!

In parts of France they know how to order contempt with a chaser of disdain.

Later, we checked out of our hotel Bastille and reconnoitred with the Bourgeois family in their beautiful modern winery and cellar with its picture windows looking out over the Mont-Damnés. Bourgeois have been farming in this area for ten generations and own vineyards throughout the appellation. Chavignol is the heart of the heart of Sancerre, and the MD is their citadel with the Bourgeois family owning by far the largest chunk of these fabled hillside vineyards. (In the 11th the local noblemen would argue over a parcel of vines on these damned slopes.

The Bourgeois wine philosophy is clear: “Terroirs forms the basis of our work, and of our inspiration as winegrowers. The variety of our vineyard enables us to present the whole range of flavours of Sancerre and Pouilly-Fumé.” Across the mosaic of several dozen plots of land spread across 72 hectares, they strive to develop and illustrate all the nuances of Sancerre and Pouilly-Fumé.

There are three predominant soil mixes in their vineyards. Clay-limestone, which gives rise to aromatic fruit-driven wines; Kimmeridgian marls, those memories of fossilised shells from the Jurassic era that imbue the wines with intense flavours of exotic fruits and a superb structure, and flinty-rich soils that tend to yield elegant wines with smoky, roasted notes and intense minerality.

As well as celebrating family legacy, focusing on terroir differentiation by farming plot by plot and cultivating the vines with respect for the environment, Arnaud, Lionel, and Jean-Christophe Bourgeois work together to ensure consistency of quality. The grapes of each plot are tasted so that each one is harvested at optimal maturity. They are pioneers of plot-specific winemaking in the Sancerre region.

Arnaud and I have had several intense conversations about natural wine. For him, accuracy in the winemaking is of paramount importance, by eliminating unwanted (and unwonted) aromas and flavours, so that the taster may fully experience the brilliant and variegated nuances of the special Bourgeois terroir. We appreciate the family’s dedication to make the best wines they can, and we understand that many vignerons will subscribe to their scientific approach in terms of attaining purity of expression. We allow also that wine may also be made without a safety net, and that by means of wild ferments and zero-filtration, a wine may yield an entirely different result but equally also articulates the terroir of the vineyard and the nature of the vineyard. These animated conversations will continue; the mutual respect will never waver.

To be continued in Chapter Three Part Two, two top New Worlders…