A long drive awaited us on our second full day in Cali but we had oodles of time to burn, a hungry Mustang to eat up the mileage and some touristic bucket on our list to kick over.

Big Sur is a wild hinterland-on-the-sea around the Central Coast of California where the Santa Lucia Mountains rise steeply from the Pacific Ocean. Although it has no specific boundaries it seems to include the 90 miles of crawling coastline from the Carmel River in Monterey County south to the San Carpoforo Creek in San Luis Obispo County and extend about 20 miles inland to the eastern foothills of the Santa Lucias. A more practical definition of the region is the segment of State Route 1 from San Simeon to Carmel.

The name “Big Sur” is derived from the original Spanish-language “el sur grande”, meaning “the big south”, or from “el país grande del sur”, “the big country of the south”. And not the big surf as I had previously thought.

The day started on a bright (grey) note with a visit to a beach populated by a vast herd of elephant seals who lay on top of each other in a bovine fug, occasionally flipping sand over each other and themselves. This blubber colony gave off an epic smell.

Thence began the serpentine crawl up the coast. Being a coastal kind of day the fog and dense cloud descended on the seaward side so the vistas were hazy to say the least. The forest-girt mountains inland were another matter, the high chaparral giving off beautiful herbal aromas and providing a stunning backdrop to the slow climb. Interestingly, virtually every other car coming in the opposite direction was a Mustang evidently the rubbernecker’s hire vehicle of choice in this area.

After three hours of not seeing anything we had worked up an appetite. We were also in tweesville, aka Carmel, a hobbit-house town where it looks as if the inhabitants paint their roses and cut their lawns with nail-clippers. It is easier for a tourist enter the eye of a needle then to find a place to have a late lunch in Carmel. I’ve said it, so it must be true!

And so “from swerve of shore to bend of bay, brings us by a commodius vicus of recirculation” back to the matter in hand namely the third visit on our itinerary, that of La Clarine Farm in the Sierra Foothills. El Dorado country. Hank and Caroline’s house lies up a winding track and when you arrive you run the gauntlet of happy lolling, licking tongues from Tapenade and Aioli, two of their highly interactive dogs.

We missed the place entirely on first pass, it is that snugly nestled behind the trees and beyond the ken of google maps. After some delicious cheeses and olives and a welcoming restorative glass of turbo-charged turbid pet nat called Circles Don’t Fly They Float (Albarino/Marsanne) we were given a swift tour of the winery/former goat’s cheese dairy.

Hank Beckmeyer’s approach to winemaking is very pure at La Clarine; he cultivates purity as a notion, as a reality. The wines have their own moods; sometimes charming, sometimes difficult, but essentially delicious. Hank writes eloquently and originally about the subject of terroir, which helps to give an insight into his own wines and is worth quoting in extensor:

Is terroir a quantum field? (from the La Clarine website)

When I first started out making wine in a minimalist manner, I learned a lot very quickly. Although worrisome at first, I learned that reduction can evolve into beautiful aromatics, and that the strange stages of ambient yeast fermentations can reveal complexities that a single strain inoculation never would. Sometimes, the uncertainty in how things will evolve is confounding. Mostly, it is rewarding, if one can accept the uncertainties.

I have come to see that terroir is not a completely independent, location-based phenomenon. It relies on the farmer/winemaker/vigneron being part of the equation. It is the person who steers the terroir towards an expression. This would help to explain why sometimes, when an estate changes hands, the wines are never the same as before. Or in Burgundy, where there can be multiple owners of one small vineyard. Why are the wines made by neighbors sometimes wildly different? If terroir is so site specific, so fixed, why does this happen?

It all started to remind me of a quantum field, in that the set of possibilities of a wine (from vineyard to bottle) is (perhaps) infinite. And it strikes me that these possibilities are indeed what we mean by terroir. Terroir (or the terroir-field) is not static and fixed. Rather, it is everything that can be. It relies on an interpretation by someone or something to manifest itself, much like a subatomic particle only has a position when someone is there to observe it. And like a particle, it could be in two different places (or have two different expressions) to two different observers.

Each terroir-field embodies this almost limitless set of possible outcomes. Each step in grape growing and in the cellar is a series of decisions which eliminate or restrict certain other possibilities. By choosing A, we may stop B or C from expressing itself. Or choosing A may emphasize other aspects. Our choices, pruning, trellising, vineyard layout, farming, picking, cellar procedures, etc., all serve to define one group of possible outcomes (what we would call its expression of terroir) while restricting others.

In essence, the farmer/winemaker/vigneron becomes the crucial link in allowing a vineyard, its grapes and the vintage to express itself. He or she allows a terroir to become explicit.

Seeing terroir in this way opens up so many possibilities to the farmer/winemaker/vigneron. We must, as winemakers, become aware of how our intentions and actions can support or detract from our primary goal – delicious wine. What is considered delicious is open to interpretation, too, but at least this view gets rid of the idea of a “correct” method of making a wine from a given vineyard. Now, all ideas can be explored. Some surprises may be found. New ways of thinking about wine can emerge.

The La Clarine Farm wines talk the same language, but say different things. They are delicious in that they accentuate fruit and minerals over winemaking technique, and difficult in that they are living wines and thus constantly changing their shape, occasionally going through reductive or closed phases. Wine can (wine should) have the capacity to be moody and broody; it can come from hard-boiled landscapes and ever so tricky vintages and all the steers, twists and turns ultimately define the nature of the wine. When it relaxes it is that more much enchanting.

We tasted a gorgeous Albariño (seven months on skins) from tank – like white-fleshed pear nectar; Fiano, a pet nat Albariño which was still “petting”; the Jambalaia red; and Sumu Kaw Syrah from one of the highest vineyards in the state (around 900 metres above sea level on volcanic loams on the pine-clad ridgetop). This latter shows smoke, meat, herbs and distinctive savoury components. It needs time in the big glass or the decanter to unwind.

It was a pleasure to spend time with Hank and Caroline, their dogs and imperious cats (tautology) and their bouncy welcoming goats.

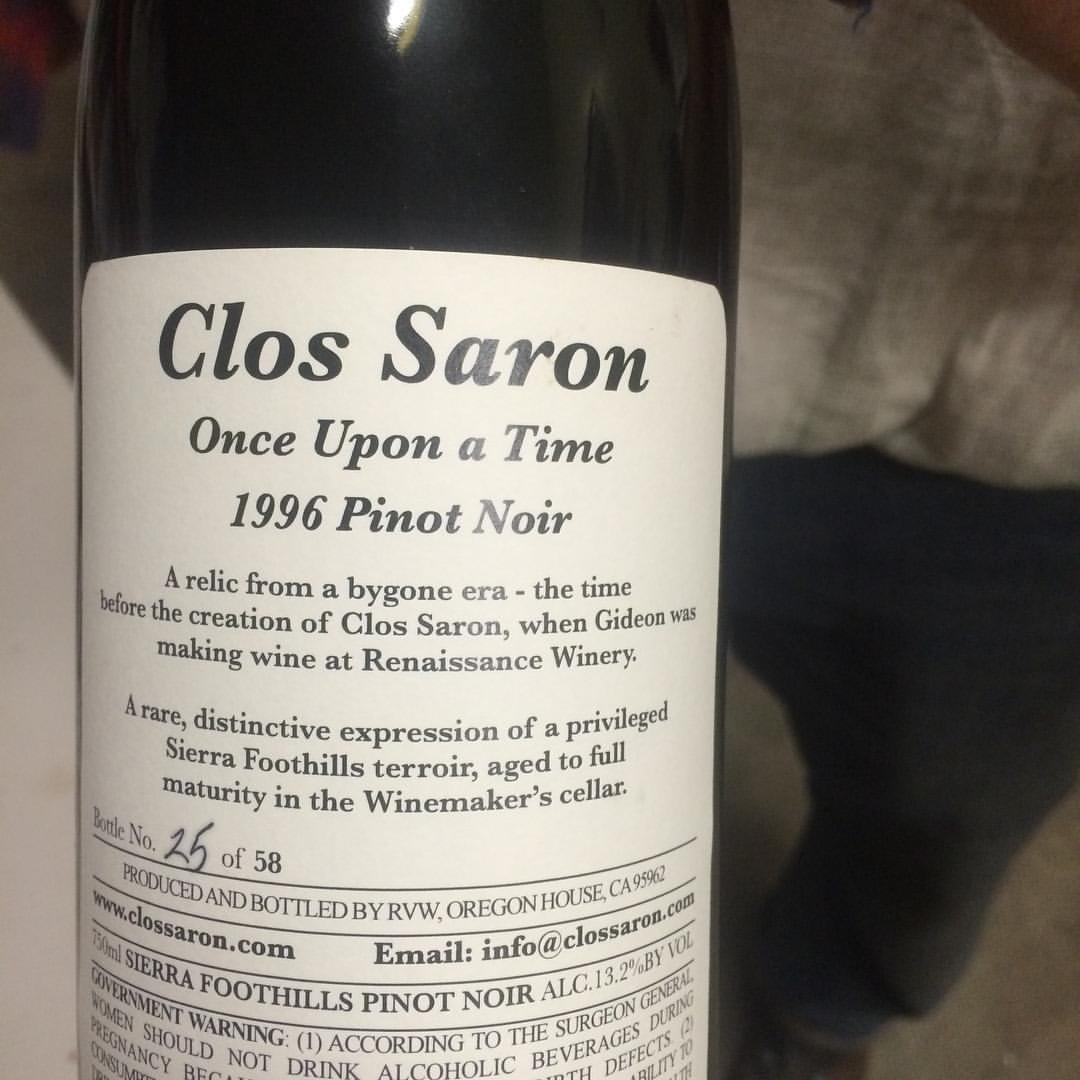

Further north, in another part of the Sierra Foothills, Gideon Beinstock (Clos Saron) is crafting his age-worthy (and age-necessary) small batches of wines that are unlike anything else coming out of California. Using traditional techniques and strict organic methods both in the vineyard and the cellar, he makes tiny amounts of Pinot Noir from his 2.2 acre home vineyard as well as a variety of unique blends from 5.5 acres of nearby leased vineyards that they farm as well.

The vineyards are densely planted, about 2500 vines per acre, and are dry farmed in order to keep yields down; ranging from as low as 1.3 tons per acre and maxing out around 2. Because their area is free of phylloxera, their vines are all “own-rooted” and many are over 25 years old.

Hand-picked grapes are crushed within 20 minutes of harvesting, followed by fermentation in old open-top oak vats using only natural yeasts. For the blends, the grape varietals are all co-fermented as Gideon believes the results are more harmonious. The wines are then aged on lees in 1 to 5 year old French oak barrels for as long as he feels is needed before being bottled, unfined and unfiltered, by hand. Production is generally around 100 cases or less per wine. Over the past 30 years, Gideon has been involved in almost every aspect of the wine industry: sales, writing, purchasing, educating, and a decade-plus long stint as winemaker for Renaissance. It is at Clos Saron, though, where he has tapped into something rare: wines that are challenging, surprising, and yet instantly gratifying. They happily defy description and convention without forgetting that, at its core, a wine should be a pleasure to drink.

Dense, yet supremely elegant, the Syrahs from rocky vineyards at altitude are world class with fine-grained tannins (Stone Soup is a personal favourite).

Changes are afoot at the winery with Gideon being able to source fruit (and direct the farming) at nearby Renaissance Vineyards where he formerly worked.

San Francisco (and Oakland) are not only the gateways to the Sonoma and Napa Valley wineries but also home to a nascent natural wine scene: Ordinaire, Terroir, Punchdown and Arlequin are specialist wine bars, but you will find excellent artisan wines pretty well integrated into many wine lists.

We also came across a host of young growers who work in collectives, sourcing interesting grapes from interesting vineyards and making low intervention wines. Not everything is amazing but the vignerons and their wines are a refreshing corrective to the prevailing orthodoxy that big is beautiful.

We met Martha Stoumen of Living Wines Collective for dinner at Bar Tartine in San Francisco. She is one of a quartet of keen-as-mustard young vignerons, winemaking school friends who share a passion for traditionally made wines and good farming practices. The collective was born when they returned to their native California from apprenticeships abroad and realized that there was a huge void to fill when it came to finding wines made naturally from organically grown grapes. These friends make wine under three labels: Elizia (Martha and Diego Roig), Les Lunes (Sam Baron and Shaunt Oungoulian) and Populis (all four of them). We carry the Populis white, a blend of Chardonnay (76%) and French Colombard (24%) and the red (100% Carignane, old vines). The former has ripe apple fruit, yeast, cheese rind, and volcanic minerality on the nose. The palate hits with ripe Chardonnay and savoury flavours, but the laser like of acid of the French Colombard and a bit of spritz keep this wine fresh.

One of the vineyards is remarkable. Located at the base of Mt. Lassen the Dobson vineyard resides at the southernmost point of the Cascade Range. The soils are from the Cohasset series, which are deep clay loams formed from decomposed volcanic rock. Mt. Lassen has been active for millions of years, giving very heterogeneous and complex soils in this area. The high elevation vineyard site of 2800 feet (850 m), and the constant cold air flowing down from the perennially snowy peak of Mt. Lassen, gives cooler temperatures throughout the growing season. The Chardonnays from here certainly pick up that volcanic minerality alluded to above.

We also had dinner with genial Matthew Rorick of Forlorn Hope at Kin Khao, a stunningly good Thai restaurant in the so-called Tenderloin district of San Francisco. Matthew’s philosophy is straightforward:

“The Forlorn Hope wines were born to connect the thread between California’s boundless viticultural potential and its diverse viticultural history. In addition to the vines my family and I farm, I work with a handful of growers across the north of the state whose plantings might otherwise be misfits: the uncommon sites and varieties that pay tribute to California’s eclectic and often unexpected viticultural heritage. Taking cues from the stones and soil, I endeavour to interrupt the natural development of each of his wines as little as possible in order that the character and uniqueness of each vineyard site may take centre stage.”

After reading a book about the Duke of Wellington’s peninsular campaign against the French, Matthew became intrigued with “forlorn hope” – a permutation of “verloren hoop,” Dutch for “lost troop,” both of which refer to soldiers chosen as the first wave in an offensive. Massive casualties were a way of life, but survivors reaped significant benefits. He has marshalled his own army of unlikely grape varieties and blends – Alvarehlo, Tinto Cao, Verdehlo, Albarino, Trousseau, Barbera, Picpoul, Ribolla Gialla… There’s even a Gemischter Sotz blend of forty or so Germanic/Austrian co-fermented varietals. We assayed his Trousseau which was a palely-loitering delight. Unobtrusive and juicy on its own, it effortlessly washed down the complex and explosive sweet and sour spicy flavours in our Thai meal. An Albarino (from the same vineyard as the La Clarine version) evolved noticeably in the glass and also proved an adept partner with our multi-plattered extravaganza.

Pingback: Letter to and from America: Part Five – Natural Wine in…Vermont?!