Jeff Vejr is the owner/winemaker of Golden Cluster. He sources grapes from one of the oldest vineyards in Oregon. His Semillon grapes are the oldest known in the Pacific Northwest.

Potted Autobiography

Tell us a bit about yourself.

I’m not the best at talking about myself, but here we go….

I am a 3rd generation American, who was raised in the fiercely independent state of New Hampshire. Growing up on a self-sustaining farm taught me the value of taste, hard work, the beauty of seasons, and an appreciation for the history all around me. These lessons and experiences have culminated in my wine project called Golden Cluster here in Oregon.

Oregon Winemaking History

When were vines first planted in Oregon?

It is believed that the first vines were planted in Oregon back in 1847 by horticulturist Henderson Leulling (later spelled Lewelling). They were brought over in covered wagons along with 100’s of cuttings of fruit and nut trees across the Oregon Trail to the Oregon Territory. He set up a nursery in Milwaukie, Oregon and sold rootstock to farmers up and down the West Coast. Those original plants were the mother plants for most of the fruit and nut industries here in the West Coast.

A healthy vineyard and winemaking culture existed throughout Oregon from around 1860 – 1919, mostly from the strong contingent of German immigrant families that had settled in many of the steep river valleys in our state. In the Applegate and Umpqua Valleys there were the Britt, Von Pressls, and Doerner families, whilst in the Willamette Valley Reuter and Wirtz families had put down roots. They believed that Oregon’s vast system of river valleys was prime vineyard land and that Oregon could be America’s version of the Rhineland. In 1904, Frank Reuter won a Silver Medal for his Riesling at the World’s Fair in St. Louis, Missouri.

Nearly all vineyards were ripped out or lay fallow just before Prohibition (1920 – 1933) and the commercial wine industry vanished along with the maturation of our growing wine culture. Prohibition had devastating effects in Oregon. We lost at least two generations of grape growers and winemakers during that time period. There were no significant vineyard plantings from 1919 until 1961 when Richard Sommer planted a wide assortment of wine grapes at Hillcrest Vineyard in the Umpqua Valley. It shouldn’t be a surprise that he planted mostly Riesling and Cabernet Sauvignon, with small parcels of Gewürztraminer, Sylvaner, Chardonnay, Merlot, Malbec, Sémillon, Sauvignon Blanc, Carignan, and Pinot Noir. The first planting of Pinot Noir in Oregon is accredited to Richard Sommer. While he is famous for being the first in Oregon to plant Pinot Noir, I think this really belittles his greatest achievements, which are; being the forefather of our modern era of Oregon wine, being Oregon’s first post-Prohibition vigneron, and the first vigneron to release a commercial wine; the 1963 Riesling. Like Oregon, Richard Sommer is about more than just Pinot Noir.

Who were the pioneers of Oregon wine?

![David Lett in his cellar c. 1970s. [Source: Linfield College]](http://blog.lescaves.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/David-Lett.jpg)

Why was Pinot Noir chosen to be the grape of Oregon?

In 1979, David Lett’s 1975 Eyrie Vineyards ‘Reserve’ Pinot Noir took tenth place in a blind tasting at an event in Paris called “Wine Olympics” conducted by the French magazine Gault-Millau. This naturally sent shockwaves (either real or contrived) throughout the wine world, especially Burgundy. Robert Drouhin of Maison Drouhin famously demanded a re-match, and out of the wines in that blind tasting, the same 1975 Eyrie Vineyards ‘Reserve’ Pinot Noir bottling placed 2nd to the 1959 Maison Drouhin Chambolle-Musigny. Once news got back to Oregon that one of our local Pinot Noirs placed well in two blind tastings in France local people really got behind the grape and became interested in our burgeoning wine scene. Ever since then, Oregon has been synonymous with Pinot Noir. Unfortunately, many have bought into the notion that Oregon = Pinot Noir and/or Oregon = Burgundy. What is rarely mentioned is that in the same 1979 Gault-Millau tasting, the Pinot Noir that placed first, was the 1976 Tyrrells Wines ‘Vat 6’ Pinot Noir from the Hunter Valley, Australia. Yet, in 1987 the Drouhin family decided to plant their first vineyard outside of Burgundy in the Dundee Hills of Oregon and not in the Hunter Valley, Australia. This helped to cement the perception of Oregon as Pinot Noir country.

It appears that these global tasting events were popular in the late 1970’s, as it was the Judgment in Paris tasting in 1976, hosted by Steven Spurrier that sparked all of the excitement in California Chardonnay and Cabernet Sauvignon. The results of these two tastings helped to legitimize domestic wines, since up until the late 1970’s most wines consumed in the United States were European. You can point to the rapid increase in the overall consumption of wine here in the United States to the aftershocks of the Steven Spurrier and Gault-Millau tastings.

Is its terroir and climate conducive to Pinot or has Oregon wanted to market itself on the potential of this grape?

There are places in Oregon where Pinot Noir can shine, but they are limited and they are not always located within the Willamette Valley, where most of the Pinot Noir is currently planted. We are still decades away from being able to define where it preforms best. We have very little in common with the terroir of Burgundy. For starters, we have ZERO Kimmeridgian soils here. Instead, we have lots of volcanic (Jory), windswept (Loess, Laurelwood), sedimentary (Willakenzie, Bellpine), and alluvial soils. I’d guess most of our Pinot Noir vines in the Willamette Valley are Dijon clone, yet we are not planting in the same soil types as Dijon in Burgundy. What we have in Oregon are our own versions of Pinot Noir. There is too much emphasis and energy in trying to benchmark Oregon to Burgundian wines. It’s not the best comparison. These are two very different places and resulting wines. Of course, these comparisons are natural given that the primary red grape is Pinot Noir. There are probably areas for understanding, but ultimately it is up to Oregon to understand itself through our own history, our own soils, our own climates, and our own reality. Currently, we don’t have the cultural wisdom that derives from generations immersed in the sense of place.

Unfortunately, trade organizations want the consumer to think that brand Oregon = Pinot Noir. This mentality and marketing strategy has done the wider Oregon wine industry a great disservice as, in my opinion, Oregon has some of the most dynamic terroir on the West Coast with profound areas that produce an incredible array of wines. For instance, Syrah performs exceptionally well in both in the southern part of our state and certainly in eastern Oregon. In fact, the highest scoring wine from Oregon is not a Pinot Noir; it is a Syrah from Milton-Freewater in eastern Oregon.

There are maybe 9 primary soil types in the Willamette Valley; in the Umpqua Valley there are around 120. The microclimatic and geological diversity in the tiny Columbia Gorge is incredible and amazing (and amazingly different) wines are being produced here. There’s been such a narrow focus on one area of our entire state with one varietal being marketed, that we are effectively sacrificing a long-term wine culture in favour of short-term economic gain.

Some of us don’t wear these blinders and would like to change the perception of Oregon wine. It is about much, much, much more than just Pinot Noir. For us, the story is deeper – and more inclusive. The tide is turning with some very exciting burgeoning projects. One day Oregon will be known as more than just being a one-trick-pony.

Has the handling of Pinot Noir altered/progressed over the years?

Yes, as is the case with most varietals; once a wine receives a high score people will chase the profile of the wine that attained the score. As certain Oregon producers attained greater recognition from the glossy magazine, prices went up, and others began to use similar methods in the cellar and/or wanted to source from the same high-scoring vineyards. We are still living in an age where the consumer subscribes to “bigger is better” and those 92 points actually mean something! Many folks are still talking about extraction and power instead of grace, levity, brightness, and layers of aromatics and there is more talk about “this is what that customer wants” than “this is what our soils and climate allow us to make this vintage”. People are more focused on making a sale by creating something that is similar rather than on making something truly individual and profound. Certainly, we are not the only wine region with this problem.

Where is the main market for these wines?

Oregon has been successfully marketing its Pinot Noir as a luxury brand since the early 2000’s. Obviously, the Oregon market is strong, as is New York City; Birmingham, Alabama, and Washington D.C.

Do Oregon wines complement its cuisine?

Yes, up and down the coast we have a bounteous seafood that goes very well with many of our white wines. Inland, we are blessed with hazelnuts, a huge variety of mushrooms, and thousands of acres of organically grown fruits and vegetables. For me, the best Oregon Pinot Noir retains that mushroom-y, forest floor note, with hints of tart red berries. Pair that wine with Oregon-raised lamb or pork with freshly foraged mushrooms and you have the quintessential (Oregon) culinary experience.

Golden Cluster

Who was Charles Coury?

He was a brilliant man who had an incredible vision for Oregon wine. Between 1961 and 1964 he visited many wine regions in France, and spent a lot of time in Alsace, in particular. While he was finishing his Masters in Horticulture from UC Davis back in 1964, he was invited to study at INRA in Colmar, France for about a year. He travelled up and down Alsace talking with growers. He studied the relationship between clonal material, soil types, and climatic conditions. At the time, Alsace was a very advanced viniculture area and were using stainless steel tanks and cooling systems in the winery that were not as prevalent in the U.S.A at the time. Mr. Coury came back energized with this new information believing that Oregon could be similar to Alsace, Champagne, Burgundy, Mosel, Switzerland, or a even a combination of these regions. He also brought back his own selection of “cuttings”, otherwise known as “suitcase clones”. One of these was a very rare clone of Pinot Noir whose origins still remain a mystery. My research points to Alsace as the origin of his clone. We will know conclusively in the next few months after the final DNA sequencing has been completed.

The majority of his instructors at UC Davis told him that it wasn’t possible to ripen grapes in Oregon, but, after careful consideration, he and David Lett convinced each other that coming to Oregon was a safe bet. Keep in mind that at UC Davis in 1964 there were four students in the entire wine program! Those being Charles Coury, Bill Fuller, David Lett, and Bruno Pilone. Three of the four chose to come to Oregon against the advice of their instructors. A few years later, Richard Sommer and Dick Erath attended UC Davis. Richard Sommer already had an established vineyard in Oregon and he helped to convince Dick Erath to make the journey up North as well.

During 1964 David Lett also travelled to France, visiting Burgundy. He also traveled to Portugal and considered planting a vineyard there. Coury and Lett were very similar men and yet also very different, mostly due to the difference in age. Coury believed Oregon was comparable to Alsace and Champagne. David Lett, well, he was a fan of Burgundy, although, it should also be remembered he is accredited with planting the first commercial Pinot Gris in the United States (in Oregon). Charles Coury loathed that grape, much preferring Pinot Blanc. Fortunately, they both chose Oregon and without their determination and vision, the Willamette Valley would not be where it is today. Shortly after they arrived there they fell out, their relationship becoming combative and later non-existent. It is a real tragedy that the rift between them was so strong. I think our wine region would look much different had they remained in an alliance.

Charles Coury was not only one of the first to plant vineyards in Oregon and make wine, but in 1980 he started the first microbrewery in Portland, Oregon. He helped to ignite not only our state’s wine industry but our extremely successful beer industry as well.

There is a common misconception about Charles Coury as a winemaker. They say he was not a very good one. However, back in 1975 Oregon was visited by one of the most respected wine voices of the 1970’s; Prof. Pascal Riberéau-Gayon from Bordeaux. Prof. Riveréau-Gayon is quoted in the Oregonian Newspaper as saying “Forest Grove winemaker Charles Coury is one of the world’s 10 best-known and respected winemakers. His opinions are sought on every continent. His research is laboriously translated in every region.” In the same article, Prof. Riveréau-Gayon also wisely stated “I find that the Oregon whites are generally superior to the reds” and that “each region, has to develop its own personality” and finally, “The Oregon winemakers should not try to imitate the Napa wines but rather develop wines with an Oregon personality.” Other tastemakers of the day also chimed in on Mr. Coury’s talents. The famous American wine writer Creighton Churchill is quoted as saying that “Coury’s Pinot Noir was the best in America.”

Mr. Coury did not suffer fools gladly. His wit, energy, personality, bravado, and intellect certainly rubbed some people up the wrong way. He had his hand in every aspect of

the Oregon wine business from 1965 – 1978. He taught wine classes at two different Community Colleges that were a 4hr drive from each other. He blanketed the state looking for prime vineyard spots. He gave away and sold cuttings to farmers who had plots of land that he felt would be exceptional for wine grapes. He was ahead of his time regarding viniculture, branding, labelling, and he was a firm supporter of the modern advances in winemaking at the time. He was an early adopter of stainless steel tanks, destemmers, and sorting tables. It is clear that he had the roadmap in his hands, but his is a cautionary tale that you cannot do everything yourself. Being a pioneer requires amazing management skill, investment, collaboration, a team of people who are as passionate or equally passionate about the venture as you, and a great bit of luck and timing.

He was forced out of his winery by his business partners in the spring of 1978, about a year before the news broke about the 1979 Wine Olympics tasting. I often wonder what would have happened had he remained in our industry for another year. The momentum hadn’t even started yet. Sadly, he wasn’t around to see the blossoming of the wine industry he helped to create.

There is a great quote by John Henry that encapsulates this: “The first guy through the wall, always gets bloodied. Always.”

Charles Coury got the bloodiest and, sadly, very few people in our wine and beer industries know who he is. His legacy has been nearly invisible and I find that highly unacceptable.

Tell us what you discovered about his vineyard?

Back in the late 90’s when I was just getting into Oregon wine, I did a lot of research on wineries that were located in the same county where I was living. One of the first ones that came to my attention was David Hill Winery. I remember driving up there and thinking I was lost, because I had found myself driving up an old dirt road. I thought that I must have missed a turn somewhere. Sure enough, as I was looking for a place to turn around the sign and entrance to the winery was in front of me. I can still remember seeing those old vines for the first time. It was a moment that made an immediate impression on me. Now and again I would drive up there, usually when I was trying to impress someone. It is such a hidden hamlet, such a unique vineyard in Oregon. It has a mystique that is hard to describe.

It was in April of 2013 when I stumbled upon the Sémillon up there. I was filming my friend Barnaby Tuttle of the Teutonic Wine Company. Barnaby makes a wine out of Sylvaner and Chasselas from the original Charles Coury plantings. I remember rounding the corner of the winery building and coming upon these huge vines; the biggest in the vineyard. Barnaby asked what they were and he started laughing out of surprise and awe when the vineyard manager told us, Sémillon. I remember Barnaby grabbed a vine very instinctually. You could tell how moved he was. I got it all on film and it is the opening scene on the trailer I have on my website. The next day he called up to David Hill and asked to buy the Sémillon on my behalf. The 2013 ‘Coury’ Sémillon from Golden Cluster is the first commercial release of this varietal and the 2nd 100% Sémillon ever made off this vineyard in 49 years.

But Sémillon is not the only unique variety at this vineyard. As is the case with many of our founding vineyards, they were planted essentially as test blocks. The original Charles Coury vineyard was famously planted to Riesling, Pinot Noir, Sylvaner, Gewurztraminer, Pinot Blanc, Gouges Blanc, Pearl of Csaba, Flora, Chasselas, Muscat, Chardonnay, and about 10 plants of mixed reds that are still a mystery.

What I find really interesting was his disdain for the clonal material that UC-Davis had at the time. Nearly all of the plants he put in the ground were cuttings, both legal and illegal. Obviously, there was something that he did not like about their plant sources.

What made you want to make the Golden Cluster wine?

When Barnaby and I were driving back to Portland, I couldn’t contain my thoughts. This is the oldest existing Sémillon in Oregon and possibly the Northwest. This is one of the most historic vineyards in Oregon. I HAVE to make this. I truly felt a call of duty.

I set out to research everything I could about the vineyard, about the history of the winery, and I wanted to learn more about the man who planted these vines. Surprisingly, there isn’t much information regarding Charles Coury. All mentions of him had ceased after 1978 when he left the wine industry. His brand vanished, the vineyard was renamed, and a new brand was started. That venture lasted barely two years, and then folded. Then sadly, the vineyard lay fallow for a decade. Can you imagine?

As I began to do more and more research I began to empathize with his fate and so I began to dig deeper. The more I’ve learned, the more I read, the more people I talked to, his story just seemed like a Greek tragedy. There is so much misinformation on this brilliant man, I just tried to put myself in his shoes and felt compelled to make a wine that would show what could be done off that historic vineyard that he planted. Walter Benjamin said “History is written by the victors” but I say, “History is also written by those who refuse to forget.”

When I started this project there was a lot of serendipity too. I got a call from my father one day telling me to come down to his workplace. When I got there, he opened up the trunk of his car; there were about four huge boxes of old books. One of his customers was about to take them to the dump. I started pulling books out and looking at them. They were old wine books from the 1960’s and 70’s. One of those books was “The Winemakers of the Pacific Northwest” by Purser & Allen. In that book, there was a great historical overview of the Oregon wine scene in 1975 and a section dedicated to the Charles Coury Vineyards. Near the end of the summary, there is this line:

“In exceptional years, the winemaker does limited bottlings of outstanding White Riesling and Pinot Noir. The wines boast a special “Golden Cluster” label.”

After I read that, I knew that I had found the name of my winery or, more accurately, it had found me. It also made sense since Sémillon is also known as the golden grape, the wines of Sauternes being known as golden wines and the 2013 vintage was nearing the golden anniversary of the vineyard itself.

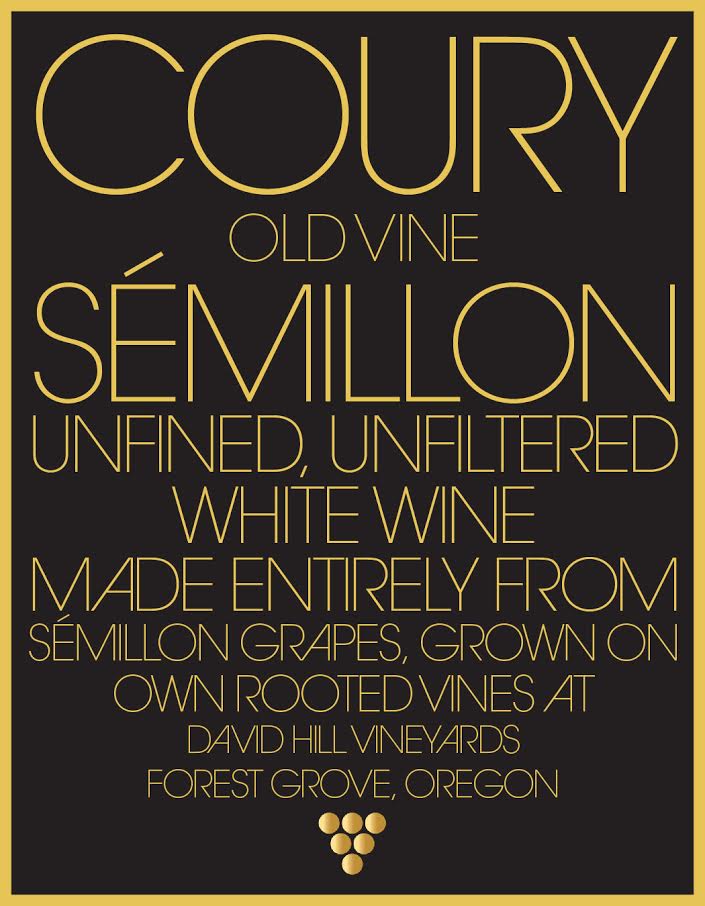

My labels are thus a blatant homage to the labels that Charles Coury used for his wines from 1974 – 1977.

I honestly was never really interested in making wine in Oregon unless it was from an old vineyard. Those vineyards are few and far between and access to them is even more rare. There’s a great story here and I want to help tell it, first by making a wine, secondly by putting his name in the air, and third, by continuing to research and report. I want Oregonians to be curious and proud of their young wine history. Charles Coury laid down a gigantic foundation for us all and yet his name is barely a whisper.

What are the properties of the Semillon grape?

I think many people would say that dry Sémillon exhibits notes of lemon balm, lemon zest, lemon rind, beeswax, and lanolin. It tends to be a wine with lower acidity. However, I do not find that with my Sémillon.

Would you describe the wine?

Vintage 2013 brought a tropical rainstorm during harvest. It was very warm with very strong winds, and heavier than normal rains. The warmth and wet brought on severe mildew pressure and botrytis. It devastated Pinot Noir vineyards all over the valley. I was not unhappy however, because Sémillon and botrytis are not mortal enemies! I do like a little “wildness” in my white wines. I have with great affection, memories of some of the dry botrytized Chenin Blanc from Domaine du Juchepie from Faye-d’Anjou and some of the dry botrytized Gros Manseng from Camin Larredya in Jurançon. Sometimes the most challenging vintages with ugly and gnarly clusters can produce some of the most unique and compelling wines.

I wouldn’t describe my 2013 as classic Sémillon. It is very bright, with high acids. It’s got very pronounced beeswax flavour layered throughout it, with a very citrusy scent, and a mushroom-y note that I really love. It smells like a fall and winter wine to me. I crave for a plate of Chanterelle risotto every time I open a bottle. This is a savoury white wine for sure. There are not too many examples of that from these parts.

Bravo!

Pingback: Chatting with Jeff Vejr, Oregon Winemaker. Part Two

Pingback: Wine is Serious Business | Episode 289: An Unusual Trio