Continued from Part One…

Air apparent and slow-cooked wines

Managed oxidation, the type of barrels, the quality of the lees, the temperature (and temperament) of the ferment (and the naturally-allowed malolactic) are part of the enrichment process. Natural vignerons in the Loire use long and slow ferments animated by strong indigenous local yeasts in large wooden formats, a kind of slow cooking that confers exceptional depth of flavour. Deliberately oxidative wines are made from Anjou to Touraine ranging from the sublime Chenins of Mark Angeli, Stephane Bernaudeau & Jean-Christophe Garnier to the vibrant Romorantins of Thierry Puzelat, Claude & Etienne Courtois and Hervé Villemade. Jean-François Chene even makes Jurassic sous-voile wines that mature under a yeast veil for six years before release. All these growers’ wines may be marked by natural process, but the winemaking rarely impedes the expression of terroir. It is more as if the wines have breathed deeply and are truly fortified for their long journey and have secrets which will be revealed when they are good and ready.

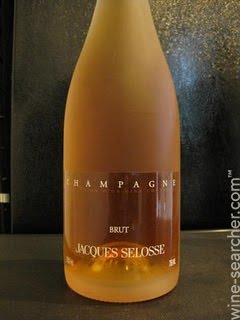

In Champagne, Anselme Selosse (amongst others) has also drawn valuable lessons from Jura winemakers and exposes his wines to oxygen early in the winemaking process as he believes that this makes them more resistant to harmful oxidation in maturity. One of his favourite sayings is that ‘my wines and oxygen are good friends’.

Sue Dyson and Roger McShane in their excellent article on the subject cite Selosse and Patrick Javillier (below) as growers whose wines are positively nourished by exposure to oxygen during vinification.

Another person who shares this view is Patrick Javillier who wine writer Clive Coates calls “the King of Meursault” – one of the top areas in Burgundy for the production of white wines. He also makes a superb Corton-Charlemagne. However his attitude to oxygen is different to other wine makers in the area. He does not mind oxygen and also sees it as his friend.

He presses his grapes in open tank presses where the juice and the must both make contact with the air and hence with oxygen. Once the wine is in barrels Javillier uses bâtonnage (stirring of the lees) to produce a richer, fuller, more complex wine. However this requires the barrel to be opened and more air to come in contact with the wine. Stirring the lees also allows sulphur dioxide and carbon dioxide to escape, thus reducing their role in retarding the effects of oxygen on the wine. He is willing to sacrifice some of the up-front fruit aromas to make his wines more complex and sturdier for the long haul.

But his quest for exposure to oxygen doesn’t stop there. After almost twelve months in wooden barrels he transfers the wine to cement tanks which allow oxygen to seep through into the wine for up to another five months.

Sherry drinkers and lovers of Vin Santo, old-style Marsala and Madeira appreciate the deliberate oxidisation of wine. Although Vin Santo winemakers are moving away from the more traditional porous chestnut caratelli (barrels) where oxygen played its role over the lengthy maturation, it is still the oxidative notes in this wine that entice and intrigue.

Expectation colours perceptions of wine. When tasting a vin jaune, a sherry or a Marsala one is within a certain “umami-recognition-comfort-zone”. The oxidative clothes maketh the wine, so to speak. Even the aged white Rioja or the old-fashioned orange/mahogany-hued Châteauneuf-du-Pape will accord to preconceived views about how these respective wines might smell and taste. Encountered in other styles and grapes, however, the oxidative veneer strikes a discord, and the characteristic is judged as a fault. Examples here might be the aforementioned Loire Chenins, the foudre-aged wines of Pierre Frick and the terroir-specific Sancerres of Sebastian Riffault, but it all rather depends whether you think this particular character is an unhappy superimposition or part of the very fabric of the wine. The ox presence divides the critics and sommeliers – Bettane’s recent attack on the so-styled tarnished wines of certain Loire vignerons exemplifies a kind of dour prescriptiveness that so afflicts the wine industry – his opinion right or right. You might just as well argue that super-controlled ferments, high sulphur regimes and myriad other interventions have falsified wines by allowing inferior vineyards to produce unnaturally polished wines. The results of winemaking should not always be invariably construed as good or bad, right or wrong, oxidised (boo) or clean (divine), but seen as the culmination of a series of complex aesthetic and practical choices.

The Shock of The Old

Modern palates find it difficult to cope with dissonant flavours in wines. Just as in music you may seek rhythm and melody, or meter and rhyme in poetry, or classical proportion in painting, so the brain naturally tries to channel aromas and flavours into familiar patterns and shapes. The role of the critic or commentator, meanwhile, is to describe and simplify, put wine into familiar contexts. Non-conformist wines and winemaking end is viewed as aberrant at best, and, at worst, beyond the pale. As soon as you confront certain people with something that is notionally blemished, say a Sauvignon that is almost amber in colour and has no obvious fruity aromatics, or tannins in a white wine when you are expecting clean and cleaned-up juice, they are disconcerted for they have been taught to believe that these are deviations from the norm. Such templates need to be shattered, otherwise we will live the mappined life, forever defaulting to the safest options.

To return to our musical analogy the dichotomy between tonality vs. atonality is a product of the changing perception of theory and harmony over the historical continuum – Chopin would be slightly atonal to Bach, and Bartok to Chopin. The same thing in jazz – Ellington would be atonal to Armstrong (slightly), Diz, Bird & Miles to Ellington, and Ornette Coleman to everybody. It’s a matter of what is considered conventional tonal harmony by the standards of the day. What is considered atonal music currently is the 20th century composers like Wolff, Berg, late Stravinsky, Hauer, Schoenburg etc. A lot of these composers used certain techniques and theories in the pursuit of atonality – whole tone, 12 tone, tone row, microtonal, Musique Concrete etc. It’s not just the composers – music can be interpreted and re-imagined by the performers. The same applies to winemaking – current oenological orthodoxies would not have been recognised 50 years ago. Grape juice is always about potential, and all about interpretation, which is why many winemakers love to experiment. And surely this is healthy. Barthes said that current opinion (which he called Doxa) was like Medusa. If you acknowledged it you become petrified.

The styles of wines they are a-changing and will continue to change. Some natural vignerons have chosen to uncouple themselves from the orthodox theories of cool ferment, closed vat, cultivated yeast because they feel that the wine cannot breathe in such an inert environment, and imprisoned by technical trumpery, will lose its soul.

A Wine is a Wine is a Wine

Many in the trade are in jobs where they are ultimately responsible to the end product user – a spade should therefore be a spade – a Sauvignon identifiably a Sauvignon – there should be square wines for square times. But not all drinkers are square.

It is also presumptuous (but it happens in all walk of life where critics critique) to believe implicitly that one knows better than the artisan-vigneron. Just like drinkers and wine critics, artisan winemakers are certainly not infallible, but their actions in the vineyard and winery determine the final individuated personality of the wine. And the wines are usually the way they are for many reasons. Decisions, such as topping or not topping up barrels, how much sulphur to use, to push for malo or not, to let fermentation take its natural course, in other words, all the physical choices of winemaking, will influence the development of the wine itself. For me, however, the paradigm of good winemaking is knowing when to step aside and leave the wine to its devices.

When I see the fault-sniffers, reduction hounds and oxidation haters reducing (no pun intended) wines to the sum of the aromas they’re not sure about, I know that wine tasting has become a cognitive demi-science and lacks an emotional, instinctive dimension. One hears stories of growers like Teobaldo Cappellano who banished journalists from his cellars because of what he perceived as the invidious practice of marking wines rather than tasting the wines for what they were.

The Year of the Ox

I prefer to talk about flaws rather than faults. Faults do exist, of course, but they are terminal and devour the wine. Flaws serve to highlight other aspects of the wine; their imperfections are part of the whole and are often beautiful in themselves.

“Oxidized flavours can be difficult if you’re not familiar with them. All the fresh fruit aromas and tastes diminish, making way for cooked or candied fruit; nutty, yeasty flavours; and a ton of complexity. Fans of these wines find their individuality and character is unsurpassed and, because of that, they are some of the most fascinating and compelling wines in the world.” Joe Campanale (Owner of Anfora Restaurant, New York)

Oxidative wines will not be everyone’s cup of slightly browning tea. But there is no reason to get aerated! Horses for courses, and all that. And it all depends on the wine as well, naturally. The wines do have something different about them and for those who have become attuned to the aromas, flavours and textures they offer a mixture of challenge, excitement and immense pleasure.

Pingback: Wine News 24 June to 1 July | winetuned