I am at a natural wine fair in Vienna. Growers and visitors come together. They drink wine, they talk, they learn about each other. The fair is about sharing wine and ideas and making friends.

Wine, fermented grape juice, is just a drink. Or is it? Of course, politics will seep into every aspect of the wine world. That politics may take the form of the choice of the individual to express him-or-herself in a way that goes against conventional wisdom, to militate against regulations (such as appellation or other governing controls). Politics is manifested in the very structure of wine institutions; politics is evident in associations set up to bring growers into groups; in the nature and composition of wine competitions, in the organisation of wine fairs, and the syllabi in wine schools. Politics reflects a human and societal need to control and compartmentalise, to interfere, to pass laws, to create clubs and hierarchies. And for every political culture, there is a counter-culture.

The divide between families and friends drinking the fruits of the vineyard that they are sitting in and enjoying freewheeling discussions about wine and the gospel of narrow chemical prescriptions as preached by wine schools could not be wider.

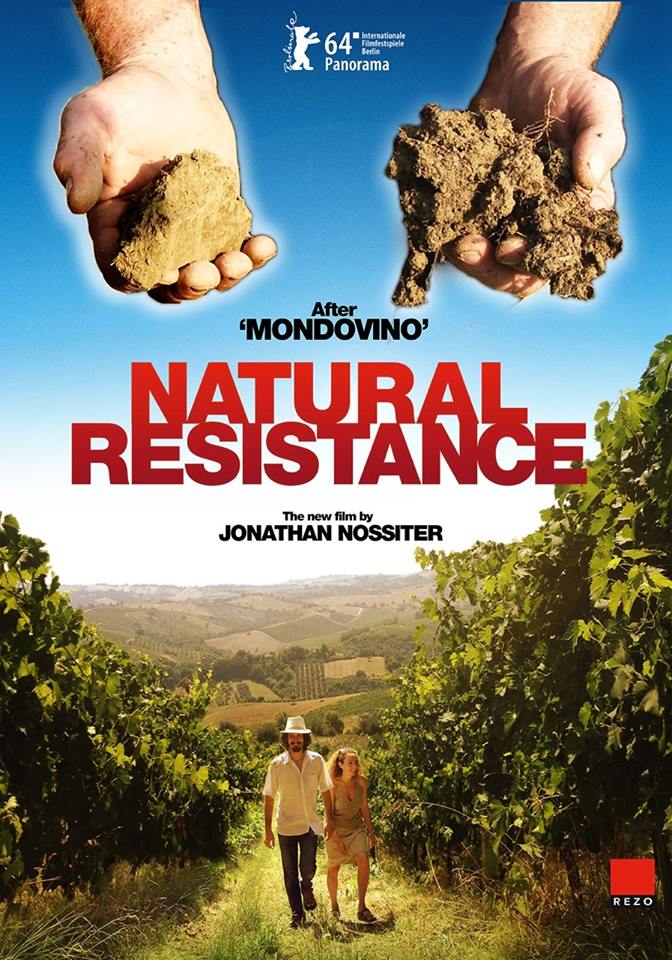

There is a lovely scene in Jonathan Nossiter’s Natural Resistance in the vineyard of La Stoppa, owned by Elena Pantaleoni, wherein we are invited to the table to enjoy the company of friends, family and work colleagues as they have lunch. As the meal progresses and the wine kicks in (it is a golden-hued skin contact wine that seems to capture and then radiate out the sunlight) the mood changes from intellectually passionate, to serious, to confidential, to teasing. We can see that wine is the catalyst for, and the background to, the discussion, the emptying bottles showing that the proof of pleasure truly is in the drinking.

Elena’s niece (who is studying oenology) remarks that all they teach you at wine college is to use this chemical or that. They never teach you history, culture…Wine is a scientific problem to be solved, it exists as a series of equations and finite options, and viewed as set transformations achieving settled objectives. The divide between families and friends drinking the fruits of the vineyard that they are sitting in and enjoying freewheeling discussions about wine (the politics, the culture, the people, the actuality of the wine) and the gospel of narrow chemical prescriptions as preached by wine schools could not be wider.

Asseverating that wine is surely made to be enjoyed, to bring people together around a table in the jolliest fashion, seems unnecessary, yet criticism, by constantly arbitrating on personal taste, has (over)colonised our enjoyment of the product. Where wine is appreciated as an artisan product, where deliciousness is prized, where drinking good wine is the catalyst to bright conversation, the seasoning for food, the foundation for camaraderie and the instigator of pleasure, loosening inhibitions and kindling the imagination, then there is indeed truth in wine, albeit you never see it listed in the ingredients on the label.

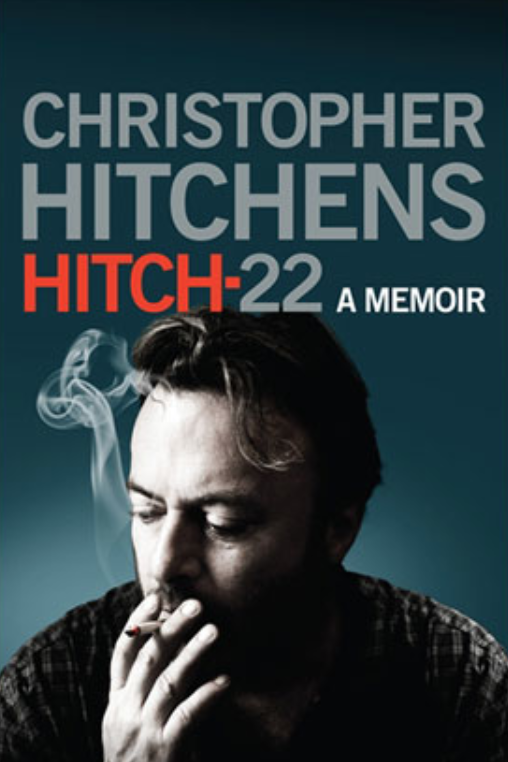

Christopher Hitchens, a man of many words and almost as much liquor. He brings together the Dionysian, aesthetic and humanistic reasons for drinking:

‘Alcohol makes other people less tedious, and food less bland, and can help provide what the Greeks called entheos, or the slight buzz of inspiration when reading or writing. The only worthwhile miracle in the New Testament—the transmutation of water into wine during the wedding at Cana—is a tribute to the persistence of Hellenism in an otherwise austere Judaea. The same applies to the seder at Passover, which is obviously modelled on the Platonic symposium: questions are asked (especially of the young) while wine is circulated. No better form of sodality has ever been devised: at Oxford one was positively expected to take wine during tutorials. The tongue must be untied. It’s not a coincidence that Omar Khayyam, rebuking and ridiculing the stone-faced Iranian mullahs of his time, pointed to the value of the grape as a mockery of their joyless and sterile regime. Visiting today’s Iran, I was delighted to find that citizens made a point of defying the clerical ban on booze, keeping it in their homes for visitors even if they didn’t particularly take to it themselves, and bootlegging it with great brio and ingenuity. These small revolutions affirm the human.’ –Christopher Hitchens, Hitch-22: A Memoir

Affirm the human indeed. It’s nice to abandon logic (to be an uncritic, as it were) and the habit of mind that would “murder to dissect” (to quote Wordsworth) wine and to go with one’s tastes and with what one feels. So many of our responses are mediated through the thick gauze of criticism that we utterly neglect the hedonic, sensuous appeal of the wines in favour of brute diagnostics.

Wine permeates religion, art and everyday culture in so many countries. It is symbolic of God’s love, and drunkenness is an ecstasy, an abandonment to that love. The Masnavi of Hafiz, The Rubiyat of Omar Khayyam, The Khamriyyat of Abu Nuwas show the liberating and civilising effect of wine. In Georgia the first Christians adopted the native grapevine, intertwining (inter-wining?) it in their own iconography. Winemaking was taught in monasteries; truly it was something that nourished the human existence. And today wine, with its 8,000 heritage, is part of Georgia’s singular cultural identity.

Wine permeates religion, art and everyday culture in so many countries.

Over the centuries vine farming helped to subtly shape the landscape. The vines were part of the landscape, however, one element in a polycultural whole. The post-war industrialisation of farming practice has witnessed a change towards a monocultural approach to farming. Wine is viewed as a product, for better or worse, and farming is the brute means of production. This leaves a political (and ethical) choice -to use and abuse the land to grow grapes to make a certain product, or to treat the land with respect, to put back in as well to remove, so the land is healthy and the environment is stewarded. This choice is not simply about whether to apply organic farming methods, but a deeper one about respecting the environment, assisting in the regeneration of the land and looking to the future.

Back to Natural Resistance. The movie presents the struggle of the artisan vigneron for the life and soul of the land, their land, against a bureaucratic machine (for want of a better word). The central governance where decisions are taken in secret for the so-called “general economic good” is reminiscent of Huxley’s definition of necessarianism as a kind of gross unthinking materialism. Indeed, modern agricultural methods with its battery of chemicals and interventions might surely be described as metaphor for the machine – an impersonal crushing entity, compacting the soil into neat dead impermeable asphyxiated blocks.

The depopulation and consequent industrialisation of the countryside has its roots in utilitarian philosophies such as Frederick Winslow Taylor’s Efficiency Movement. In his treatise The Principles of Scientific Management, which inspired the 1921 dystopian novel We by Yevgeny Zamyatin, Taylor writes: ‘In the past the man has been first; in the future the system must be first.’

His prescription for success is simple: ‘It is only through enforced standardization of methods, enforced adoption of the best implements and working conditions, and enforced cooperation that this faster work can be assured. And the duty of enforcing the adoption of standards and enforcing this cooperation rests with management alone.’

And thus we have government-sanctioned short-term approaches to farming based on efficiency, of squeezing the land until the pips squeak and until it can yield no more.

Where is the resistance being channelled? If you are young like Corrado and Valeria you can be optimistic, and retain the spark of revolutionary idealism. If you are older and weary of the perpetual struggle and banging your head against the brick wall of dumb bureaucracy, the drip-drip effect may erode the will to resist.

We have government-sanctioned short-term approaches to farming based on efficiency, of squeezing the land until the pips squeak and until it can yield no more.

There is hope. Natural wine, as I’ve written elsewhere, is not a movement with applied rules, but it has become a force of perceived opposition. The natural vineyard, if you like, is an amorphous collection of vignerons, winemakers, merchants, retailers, and drinkers, who are not prepared to be told what to make, what to think or what to drink. For them the DOCs and appellations rather than being the solution have become part of the problem.

Stefano Bellotti observes:

‘Because the DOCs are a common patrimony that we share in each region.

– To have to quit– But it’s no longer a common good. It is no longer. Let’s hope it can become once more a common good. The fact is we’ve had to become revolutionaries. I never would’ve imagined that. I’m not a revolutionary by inclination, for sure.

The polluters told us: “if we don’t pollute, we can’t produce.”

They sold that as modernity. As inevitable. Today it’s clear, our approach is a condemnation. They see it as a condemnation. So they want to save face and try to prove that their techno-scientific method is superior to ours. In fact they have all the weapons, legislative, legal etc. and all the power, – so that if we don’t unite – they have all the weapons to get rid of us, one after the other.

If my farm starts to lose, 50.000 – 100.000 euros a year in fines, along with other problems, like simply the time that’s wasted, then my farm will go under. Every car that pulls up in our courtyard, we’re terrified that it’s going to mean another fine. Between NAS, ASL and The Anti-Fraud Bureau, that could reach 150.000 euros this year. With a budget of 550.000, that will inflict its damage.

Small farmers are free by definition. So that means trouble. There’s nobody in a society freer than a true farmer. And, so, by definition, they’re extremely dangerous.’

Continued in Part Two…