It is very rare that we have the opportunity to take the whole sales team to a country to meet and spend time with all of our growers. This then was an amazing and thoroughly rewarding trip, one which showed why Austria is gaining such a strong reputation in the wine trade.

The personality of the growers who were very genuine, very humble – they talk enthusiastically, but they also listen intently – won everyone over immediately. They are interested in what you have to say and what you think of their wines. They also eloquently communicated their love of being in the vineyards. And no wonder! Visiting in June was propitious timing – the sap was definitely rising in the vines, the rows were covered in wild flowers, plants and grass. All the vineyards had a pulsing energy from the steep dry-stone wall terraced heights of the Heiligenstein with its butterflies and birdsong to the wonderfully overgrown biodynamic Andert vineyard near Pamhagen, in an area reclaimed from the nearby Neusiedlersee. You can only think that good things will come from such places. Diversity is further key to a country’s success – from the rocky vineyards of Kamptal with their bewildering array of soil types, home to Gruner Veltliner and fabulous mineral-edged Riesling, to the wilder vineyards of Styria on opok where Sauvignon and Chardonnay (or Morillon) express themselves so powerfully, and finally to Burgenland where growers seem to have a strong affinity for biodynamics which communicates the life of the vineyard into the wines themselves. And variety of styles and flavours…we tasted light, fresh elegant wines and wines meant for long ageing; delicate pinks, rich, spicy orange wines, juicy reds; wines made in amphorae, foudres, stainless barrels; single vineyard expressions, exotic blends and rare local grapes (Wildbacher). Above all, the wines were self-evidently the result of meticulous farming and natural winemaking and a deep love of the place from which they emanated.

First stop was Weingut M & A Arndorfer in the small town of Strass in Strassertal. The wines do two things – they respect the grape variety, terroir and tradition of Kamptal; on the other hand Martin is branching out and exploring new techniques. He is a master blender, using multiple formats from steel tanks and stainless barriques to small oak, demi-muids and oval barrels.

After attending winemaking school in Austria Martin headed off to Italy to get some practical training. He attributes much of his inspiration to two Italian producers: Ronco del Gnemiz run by Serena Palazzolo where he experienced his first full-bodied whites matured in small oak barrels, and Fabrizio Iuli. With Fabrizio he learned how to make, “complex and straightforward red wines of outstanding quality”. These two wineries sparked his interest in thrilling red wines and his passion for barriques. He said in both cases, he has also found friends for a lifetime.

When Martin returned from Italy, he and Anna moved in together, and not only did they unite their living spaces, but also their love, ideas, passion and knowledge for winemaking starting their own label, ‘M & A Arndorfer’.

The Arndorfer watchword is origin. Martin & Anna also believe that the role of the vigneron is crucial – artisanship thus is the combination of creativity, sensitivity and personality.

“Origin for us though is restricted to the vineyard and the vines. The vines soak up the vigour of the soil and their surroundings and give the grapes their unmistakable character based on their origin. Even though we do not feel bound by tradition, we want to emphasise that the influence of the vineyard is crucial to our philosophy. We are convinced that it is impossible to make two wines exactly the same if the grapes come from different vineyards, regions or countries.”

We think that the most important part of the vineyard is life and balance. Both things are very closely connected with our soils and the work/management we do with the soil. There are lot of little animals and partly very big mycelium in the soil which help the vine to get water and nutrients, but they need their “home” and food. So in our viticulture we try to provide them what they need so they will provide our vines what they need… if we assault our vines (fertilizer and herbicide) we will not have life and balance in our soil.”

They have created different ranges to capture various distinctive yet essential truths behind their vineyards and the grape varieties.

We begin with Vorsgeschmack (Foretaste), a symbiosis of the two star grapes of the Kamptal. Martin and Anna describe the wine as the beginning of a friendly talk, the prelude to a meal and the gateway to simple pleasure. A blend of 80% Grüner and 20% Riesling with the former from clay on loess soils raised in old barrels, whilst the Riesling is from old vines on primary rock but with an early pick to preserve freshness this fruity and floral white is then fermented in stainless steel. Indigenous yeast ferments are used for all the wines. The wine is balanced, the Riesling give a little aromatic zip to the solidity of the Grüner. Strasser Weinberge is the next range, comprising a Grüner and a Riesling. These wines are, in effect, vineyard reserves from the best vineyards in Strass. The Gruner is based on grapes selected from three vineyards: Strasser Gaisberg, Wechselberg and Hasel, each producing grapes which are totally different in style and taste as a result of their diverse soils and microclimates. Thus the final blend “reflects the whole village of Strass in all its complexity and variety”. The Riesling is from Gaisberg and Wechselberg on those particular primary rock soils that confer mineral tones as well as finesse and elegance to the final wine.

Certain vineyards are singled out for special treatment. The lesser-seen Roter Veltiner grows in a plot planted in 1979 on the south-western slopes of the Zobinger Gaisberg. Although the variety itself possesses low acidity, a combination of old vines and mineral soils (these being on primary rock) gives lovely textural depth to the wine. Notes of mandarin and honey are unveiled as the wine warms in the glass. Grenzenlos is also a single vineyard, this time from the Strasser Wechselberg, their oldest Grüner vineyard, planted in 1959 on clay soils with gravel and chalk. After five years ageing in stainless steel the wine spends another six months in bottle to relax. This is notably elegant and shows the personality of the grape variety in its most naked form. The upbringing of the wine runs counter to the Arndorfers belief that Grüner prefers a gentle sojourn in oak barrels.

Die Leidenschaft, Martin & Anna’s passion line, pushes the boundaries that bit further. The wines are fermented and matured in small barrels without stirring. The Grüner, for example is really spicy and herbal, the stunning Riesling from the cru vineyards with its honeyed golden plum fruit has to be sipped slowly and appreciated.

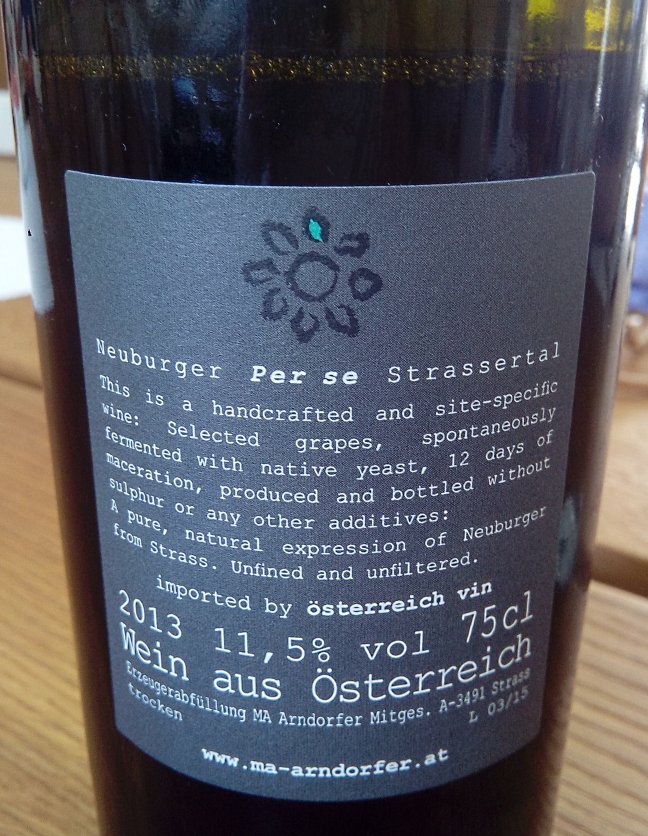

Finally, there is the natural range which reflects the playful side of the vigneron’s nature. Here one tastes a Müller-Thurgau Per Se from old vines grown on primary rock, an aromatic skin-fermented (for 12 days) orange-tinged wine made without filtration or sulphur in stainless barrels. Its companion is a truly wild Grüner (also called Per Se) with 14 days on skins and aged in old barrels with 16 months on the lees. A medicinal wine with notes of wild herbs and fennel. In the spirit of further craziness we tasted a beautiful pale pink wine called Rosa Marie which is Zweigelt fermented on Grüner Veltliner skins, to which the appropriate response is “why not?”

Martin & Anna are proud to live and work in Kamptal, especially in the Strassertale. Despite the long history of winemaking and viticulture, it doesn’t inhibit their personal approach. Martin will not dismiss the past: “Talking with the older generation provides a way of learning and understanding about the vineyards of our village; to see pictures of the vineyards from the past is very inspiring.”

For example, why was the vintage 1947 so outstanding? Maybe the sun, maybe the small crop, maybe the pruning, maybe the” trellising system”, maybe crushing the grapes in the vineyard, maybe not having a tractor, nor herbicides and fertilizers, or maybe a little bit from everything. Anyway, I think it is good to learn from our history and use the experience from older generations, but combine it with the knowledge of the present time. The cheapest thing we can do is keep thinking about our work and our decisions…History gives us a bigger background for this idea…

Is the region, or perhaps other winemakers, ever resistant to change or new ideas?

The question is: what are new ideas or changes? Most of the wineries certainly want to produce wines that show the character of the origin – village or single vineyard – to show a very typical wine from the region. Sometimes people call it traditional. I got the impression that there weren’t many growers prepared to innovate in the winery like the Arndorfers, Alwin & Stefanie Jurtschitsch, Matthias Warnung and Matthias Hager. Whilst embracing tradition in one sense they have liberated themselves from it in another. Here are growers working with, for example, skin contact, long ageing, unusual formats (eggs, stainless steel barrels, wood of all shapes and sizes), low or no sulphur. The wines look outwards whilst capturing the historic terroir of the Kamptal.

The brace of entry level wines called Handcrafted effectively flouts the appellation rules that determine that wines of origin must be filtered. These are indeed wines from Strassertal but are considered atypical because they are unfiltered. And being unfiltered they are more vinous, need much less sulphur and have a more intense character. One is reminded that appellation rather than defending quality and the expression of individuality now perversely protects the notion that wines from a region should be similar to each other.

A long lazy lunch ensued in the courtyard of Arndorfer’s where we tried those 15s already in bottle plus several tank samples. It’s a vintage of generously proportioned yet harmonious wine; it also illustrates the advantage of having many components to blend together. Terroir does not always have to be a single vineyard definition, but may refer to the different aspects and different accents conferred by different vineyards and even different parts of the same vineyard.

Riesling, for me, is the standout grape of the Kamptal with its mouthfeel and ripe clean fruit given that bit of extra by the complementary combination of lees and the cooling minerality. Arndorfer’s Die Leidenschaft was a very fine example; Austrian white wines (Gruner and Riesling) can be superficially serious and somewhat overblown with either too much alcohol or too much residual sugar. Martin’s work with different fermenting and ageing formats ensures that the wines are in contact with the lees, that a textural balance is maintained. He is also looking for essential drinkability and a fine line of acid. The wines therefore are never cloying.

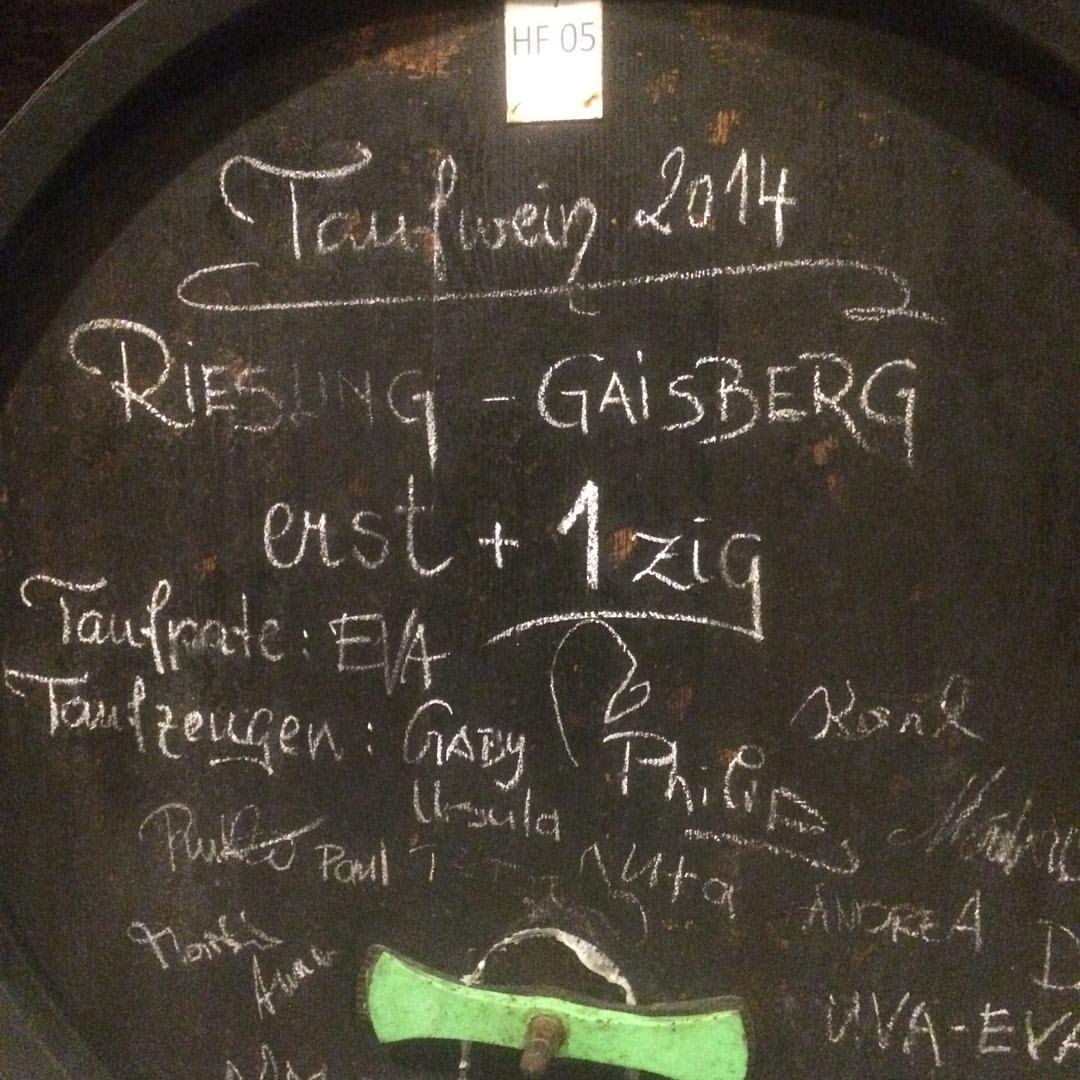

After our lengthy lunch – of seconds, thirds and fourths, we climbed heavily into various vehicles and puttered up to the south west facing terraces of Gaisberg vineyard which overlooks Strass. It was a beautiful day with excellent visibility. We walked along one of the back rows of vines next to an exposed earth bank which showed the remarkable diversity of soil types even with 30 metres or so, a mosaic of brown clays, schists, granitic sand, patches of chalk, gneiss and amphibolite. The vineyard itself was teeming with plant life and grasses, and, receiving the full force of the sun in the late afternoon, was full of light. About a kilometre away was the flank of the Heiligenstein, where Jurtschitsch own some smallholdings and our next port of call.

Weingut Jurtschitsch is a very important winery in the Kamptal, with a rich history. The press house is from the 16th century and they have an enormous 700 year-old natural, cool cellar that used to belong to a monastery. Here you can wander through almost endless passageways with an extraordinary array of barrels and foudres (one was 27,000 litres!), glass demi-johns, small terracotta qvevri and (pride of place) beautiful ceramic eggs. The atmosphere here is tranquil; this is a place where great things can happen.

Having being run by the three brothers Edwin, Paul and Karl Jurtschitsch, the family-owned winery has now been passed on to the younger generation, to Alwin Jurtschitsch and his partner Stefanie Hasselbach. This family business succession has been prepared thoroughly. The couple travelled around the world, gathering experience in New Zealand and Australia, most notably with James Erskine in Adelaide Hills/McLaren Vale. Working as interns in famed wineries in France, they got to know the French school of the Old Wine World. They had terrific fun and learned a lot. Now, they feel they can put the ideas and the experience they have accrued into practice back home in the Kamptal. When you talk to Stefanie and Alwin there is a twinkle in their eyes – they are constantly bouncing ideas off each other.

A first step was the change-over to an organic cultivation of the family-owned vineyards. They farm organically not only for the wines they are making today, but also to preserve their vineyards for future generations. They are best known for their single-vineyard wines that are fermented with their own wild ambient yeasts and gentle, traditional vinification methods.

Alwin would consider himself to be a scientist but he starts with a holistic (and environmentally-conscious) ethos. He observes the vines and understands the importance of a long-term approach in the vineyard. He and Stefanie reduced the number of wine-growing sites so that they could concentrate on the first-class appellations of the Kamptal. But all was done seamlessly with a great deal of sensitivity and respect for tradition. The wine philosophy also underwent a transformation: “Our wine style became more ‘polarising‘, characterised by the idea of terroirs without compromise”, says Stefanie Hasselbach.

They produce wines which let the vineyards and soils speak for themselves, even about the winegrower who cares for them. “Yes, we are farmers”, Alwin Jurtschitsch stresses, “this is our work, our tradition and handcraft in the best sense of the word.” In the cellar, all this is turned into a work of art. The Grüner Veltliner wines interpret the Kamp Valley’s spiciness at its finest, while the Rieslings impress with their crystalline minerality. More on these anon.

Alwin and Stefanie took us on a swift tour of the Heiligenstein vineyard. This steep Austrian hill is one of the world’s great Riesling sites and merits the abused epithet “iconic”.

Whilst voguish Grüner Veltliners thrive on the loess soils lining the Danube River, wherever enough primary rock reveals itself (as we saw with the Arndorfer vineyards) that becomes a preferred location for Riesling. The Austrian climate is decidedly continental; it’s colder in winter and warmer in summer than in Germany, for example, and the grapes can get significantly riper. Sweet Austrian Rieslings do exist, but generally speaking, the national style is dry, with the extra sugar fermenting out to produce more alcoholic, fuller-bodied wines. The Austrian government’s moratorium on chaptalization and strict yield limits ensure that this potential power is always focused and intense, never blousy or fat.

Nearly all the great spots for Riesling are in Niederösterreich, the most north-eastern of the nine states of Austria, where the Alps peter out into the great Pannonian Plain of Central Europe. This is the slice of land along the Danube that includes the wine regions of Wachau, Kremstal, Kamptal, and the vast Weinviertel. The Wachau certainly offers up Rieslings of remarkable quality, the Kamptal is considered by some to be Austria’s Burgundy, with its greatest grand cru vineyard that of Heiligenstein (if we must use the terminology of cru in vineyards for the location is only potential energy, the kinetic energy is given by the method of farming).

The terraced slopes of the Heiligenstein dominate Kamptal’s eastern landscape. This place was originally documented in 1280 as Hellenstein, or “Hell’s Rock”—most likely in reference to the hot temperatures of summer days and possibly to the steepness of the slopes – reminiscent of the Mont Damnés in Chavignol. Long farmed by monks (whose chapel still marks the hillside), the name was changed by the resident clergy to Heiligenstein, or “Holy Rock,” around 1500 for obvious political reasons. Here, the warm winds from across the eastern plain are tempered by cool evening breezes from the Waldviertel forests and the Manhartsberg mountains to the north, prolonging the growing season and guaranteeing physiological maturity. The terraced vineyards of this 30 degree slope face south toward the plain where the Kamp River joins the Danube. Although rain is plentiful the growing season is generally dry, which allows organic and biodynamic farming—flags flown by many a local grower – although it was noticeable there are irrigation systems everywhere.

The soil, dating back 270 million years to the end of the Palaeozoic era, is worthy of study on its own. Before the Alps were formed, Sahara winds blew desert sand onto the original banks of the Danube. As the river, which was more like a sea at the time, receded south, gravel was deposited; that gravel now lies deep beneath a complex mixture of weathered crystalline slate, maritime sediment, volcanic rock, and the desert sand. Heiligenstein is more of a sandstone conglomerate than primary rock (as is found in the Wachau), jutting up to about 350 metres feet in elevation and above the adjacent hills, to catch the full effect of the sun’s rays. The pitch is too steep for loess to have accumulated—though that soil type is found at the base and is the home for some spectacular Grüner.

Heiligenstein’s mix of ancient soil and rock is exactly the kind of fuel that feeds Riesling’s hunger for minerality. Given its geological structure, the wines are always very mineral-driven and well structured. Others note that the wines are dense and yet extremely fine, with a kind of showy nobility; all agree on their cellar-worthiness. Riesling ripens later than Grüner; it is tempting to go for a powerhouse style, but all the growers we visited were seeking a certain tension in their wines.

The Jurtschitsch plots on this fabled hill are inspiring places to walk. They have created small heathland zones to attract insects and creatures and restored the terraces using local stone. From the healthy soil beneath your feet, the cheerful birdsong to the vivid light bouncing off the rocks off the terraces there is a brightness and palpable energy in their vineyards.

And while the sun continued to beat down on the Heiligenstein Alwin, Stefanie and Martin cracked open several bottles (or volumes) of Fuchs und Hase Pet Nat. We stood and talked and drank and generally gawped at the incredible views before duty and cellar tasting called.

Back to the winery to sample their special project called Entdeckungen. The winery is a vast cave and is currently being reconfigured. There are lots of barrels and towering old foudres but also ceramic eggs. Alwin and Stefanie intend to work more and more with eggs.

Wildly aromatic and expressive, unfiltered and unsulphured, the wines possessed a raw juice quality. One was instantly transported to those vineyards, vibrating with life. Alwin wants his wines to vibrate in the same way. The specific terroir is one thing – Alwin, Martin Arndorfer and Matthias Warnung see the vineyard and the soils as the beginning of the process, the evolution of the wine’s identity. All the minerality from carefully nurtured soils naturally communicates itself and has to be allowed to communicate itself, but the wine’s complexity is filtered through other natural processes and winemaking decisions, shaped, for example, by the interaction of the ambient yeasts (and the subsequent ageing period on the lees) and also by the very container in which the juice ferments and matures. The extraction of flavour from the wine is not about forcing the issue but moving in different formats, thereby discovering different “taste-shapes”.

The three wines we sampled were very different. Belle Naturelle is 100% Grüner Veltliner from Langenlois. “We are not allowed to write any specific origin or appellation on the label as our Austrian “Quality-Wine-Law“ cannot handle any unfiltered or skin fermented white wines.” This wine was fermented whole bunch in a big open top wooden (red wine) fermenters. The fermentation was pretty hot and quick and the juice stayed with the skins for two weeks before racking into used oak barrels where malolactic fermentation finished. The fruit is where the skin of a ripe golden pear meets the flesh and then comes some bitterness and white spice from the lees.

Freier Loser is Grüner from the Loiserberg Vineyard. “Freier” means “free” or “liberated“. 2014 was a difficult year to get ripe and healthy berries, the volumes of high quality non- botrytis grapes being very limited. In the end Alwin and Stefanie made a single barrel which they left on the full lees until April. The wine is closed at first with a tension between lees reduction and oxidation which is most intriguing. From the colour you would think that this is a full-on skin contact wine, but this is not the case. The minerality is fantastic but you need to be prepared to roll it around your glass and in your mouth to discover the nuances.

Pot des Fleurs is fermented whole bunch in a Georgian qvevri of 550 litres and matured for 6 months on the skins. Afterwards the wine was racked into an old 500 litre barrel for 11 months. This is the most opulent of the wines redolent of fruits roasted in the oven with sugar and spice.

Liberated thinkers question every aspect of vine growing and winemaking. They are no longer slaves to convention (that convention is, at most, two generations old). Many vignerons are cultural archivists, resurrecting grapes, wine styles and traditions that were abandoned in the post-war dash towards chemical farming and flavour-stripping winemaking techniques that resulted in commercial homogeneity. They are not harking way back for the sake of it, but are conscious that history has a wider sweep than 50 or 60 years, and that to understand the future firstly you need to understand the past.

The journey of single wine comprises many steps and interesting detours. Matthias Warnung worked with Craig Hawkins who worked with Dirk Niepoort. His sensibility is similar, but his approach is necessarily different. Kamptal is not Swartland, after all. However, his mind set and approach is at variance with other local growers. With Alwin and Stefanie you have a further element in the equation. They have taken over a winery with a famous name, one that trades on its traditional image. Although it would be tempting for them to renounce everything in the immediate past you have to build on what is there already. And so they have created their own separate project to pursue their wine dreams and fantasies and will gently guide the mainstream wines into a more natural idiom. The Arndorfers are also custodians of the family business – the transformations in winemaking must be subtle rather than alienating. They have created their own label, which they have further subdivided into four further bands (rather than brands), according to the style, the feeling behind the wine, and the degree of experimentation involved.

Standing on the Heiligenstein, looking around, one can sense the past, the present and the future. The sense of place, elevated above the valley, with its amazing historical background, is powerful. Some of the walls that support the terraces are crumbling, some of the vineyards have been engineered to make tractor work easy. Some of the most stunning vineyards with the oldest vines are being abandoned – or maltreated. With love and nurturing this glorious patchwork of vineyards might be resurrected integrated into a fully biodiverse environment. This requires patience, a labour-intensive approach and an understanding of the vineyard as an organism. These qualities (embodied in the work of Alwin and Stefanie as well as Martin and Matthias) are intrinsic to the ethos of natural winemaking, which is not about neglect and abandonment, but rather a serious investment of time and effort in creating the physiological preconditions to get the best possible material from the vineyards. Thereafter, you can channel the sacred juice with all those inherent complex mineral components towards the complete wine. Or rather the wine that feels and tastes complete in itself. Terroir is about the history and the natural environment; by helping to revive that terroir in the vineyard, the vigneron may rediscover its underlying signature in his or her wines.

Dinner was at Esslokal in Hadersdorf, a restaurant on the tranquil main square of the small town. We had the whole restaurant to ourselves (they opened specially for us). The dishes were interesting and pretty filling including Grammelknodel mit Rieslingspeckkraut; Roastbeef vom Kalbstafelspitz, Erbsen, Radieschen, Sonnenblumenol, and Kuhsuppe mit Dinkelfritatten und Wurzel Gemüse, and demob-happy we sank a few beers and supped some of Matthias Warnung’s excellent Etsdorf Blauer Zweigelt Rosé and Blauer Portuguieser. For the team it was a grand day of humour and hospitality, breathtaking views and darn good food and wine.

Pingback: 2016…..so far! Look back in languor.

Pingback: 2016 in a grape pip