Revisiting Taste, Tasters and Tastings

Looking at the glass-twitchers, sniffers and slurpers at one of our recent shindigs made me think that tasting is as much about mood as anything. The more generic the tasting the more you will be seeking correctness and typicity and points of reference in the wines on display; a small-grower-predominantly-natural-wine tasting, conversely, compels one to jettison certainties and open oneself to challenge and excitement. Well, I like to believe so.

Like them or not our tastings are fun; the wines being full of vitality and dare one say, peculiar energy. These wines move by the hour, by the minute, they unfold their charms like beautiful flowers or ravel them up like boorish misers. They are as unpredictable as people and like people you can take them or leave them. What is not appropriate is to dismiss them all as bad or incorrect.

For some wines are as straight as a die, clean-fruited, simple. Others are linear, and yet others are multi-dimensional and complex. Some flirt with the edge of conventional wisdom (!) and would only be loved by the fiercest adherents of all things natural, and some might even be unacceptable to lovers and loathers alike; we expect to find more than the odd – very odd sometimes – bottle that is stinky or downright unpleasant. Do a handful of wrong ‘uns undermine the case for the natural defence? Of course not, any more than all tastings will inevitably contain wines that are imperfect, unbalanced or downright undrinkable. We should never judge the many on the basis of the few.

And whilst we never court critical endorsements of natural wine, we would, however, expect each wine to be tasted on its merits, in the spirit of open-mindedness and enquiry. Those who come to our tastings largely want to be engaged, to describe their impressions and to interact with us – for wine tasting is nothing if not a social activity as well as an opportunity to expand one’s horizons. A few may prefer to keep their own counsel, focusing purely on the objective, dredging Les mots justes from the lexicon of conventional precision, whilst a tiny minority still would sigh and roll their eyes and retreat into their critical carapaces as every wine confirms their preconceived notion that natural wines are up to no good, no how.

A mind that questions everything, unless strong enough to bear the weight of its ignorance, risks questioning itself and being engulfed in doubt. If it cannot discover the claims to existence of the objects of its questioning—and it would be miraculous if it so soon succeeded in solving so many mysteries—it will deny them all reality, the mere formulation of the problem already implying an inclination to negative solutions. But in so doing it will become void of all positive content and, finding nothing which offers it resistance, will launch itself perforce into the emptiness of inner reverie. –Emile Durckheim, French Sociologist

This could be the perfect description of the wine cynic, but is perhaps not the best analogy, as the cynic does not normally interrogate his or her opinions but tastes to reinforce an existing prejudice. It is an empty exercise, because such tangible dislike of wines is based on a pseudo-scientific belief that wines dovetail into neat categories – this is correct, whereas that is not so. Once you have painted yourself into these Manichean certainties, you cannot row back, profess doubt or even admit that there may be a relative position.

All life is a dispute about taste and tasting –Friedrich Nietzsche

So sue me for quoting Nietzsche! Taste, as the man says, is necessarily subjective and since people are individuals and not machines, they are also flawed. So taste is flawed or a flawed concept. You could get a machine to measure wines for undesirable chemical abnormalities; but who decrees what is desirable? The machine has no sense of taste or higher aesthetic purpose. Were I to program a tasting machine I would ask it to pick out higher than average sulphur levels and to assess where additives had obviously influenced the taste of the wine, for a wine made in a factory or a laboratory is so far removed from the vineyard, the grapes and the wine grower that it ceases to be a living product. Which is a fault in my book. Thus my criteria as to what makes a wine desirable or drinkable may openly contradict another person’s.

“It is good taste, and good taste alone, that possesses the power to sterilize and is always the first handicap to any creative functioning.”

So far, so relatively obvious. The rational (and intuitive) approach embraces wine by judging in the round. It is deductive as well as inductive, using all the information available to arrive at a conclusion rather than relying exclusively on imperfect sensory apparatus. It is creative as well as responsive. Yes, a tasting is many things; but in conventional circles it is often foremost an extension of the ego of the taster, it is the super-analysis of the wine in the glass at the time, rarely the contextual understanding of that wine, by which I mean, hearing the story behind it, talking to the grower, discovering the intention. Since wine is the product of natural interventions and human decisions, the more information we have, the keener our final assessment. Objectifying the process makes for an interesting yet unreliable game; the palate of the taster qua taster, trained or otherwise, becomes the sole (and arbitrary) focus. A priori knowledge is rejected, the here-and-now exalted, whilst the potential inherent prejudices of the taster (which calibrate his or her palate to “twitch” in a predictable fashion) serve to undermine all pretence of professional objectivity. This is the tricky contradiction inherent in tasting.

Wine is not just an object of pleasure, but an object of knowledge; and the pleasure depends on the knowledge. —Roger Scruton

If someone judged us on appearances and first impressions; by the way we dress, the colour of our skin, our initial behaviour, we would naturally feel aggrieved. And yet some tasters affect to judge wine absolutely in this fashion. The more complex, unknowable wines are too often rapidly dismissed and the less immediately agreeable ones are slapped down. The mutability of wines made without additives makes them tricky customers, by definition; you have to give a little to take a lot, or relax and recalibrate your palate. Once you do so the wines make sense; its characterful nature becomes a function of the wine itself rather than a loose adjunct of style. Wines do not exist to make the life of the taster easier; they may be edgy, nervous and prickly to a fault; that is their nature. The empathetic taster confronts such wines on their own terms.

My major memory of the best tastings is not of the wines in their many glories, but, a small handful of tasters, half a dozen say, who came up to me variously and commented on the wines and the tasting. Nothing specific other than they were all smiling and bubbling like a refermenting pet nat (or like any refermenting natural wine, for that matter). Imagine going to a gig of a band you barely know and you end up dancing in the aisles to the encore – that was the feeling. Yes, wine tastings can be fun, irreverent and engaging; the agenda is always about the individual wines in question; the taster is invited to leave his or her baggage at the door for maximum pleasure.

The average wine tasting, nevertheless, is the most cursory examination of the contents of a bottle. What you taste is one beesip from one bottle at one moment amongst many other beesips, sans food, in glorious (usually-humourless) isolation and minus any spirit of enquiry. When you drink a bottle of the same wine with another person you are sitting down – often with plates of food – unwinding yourself into a state of openness and anticipation. You are relaxed, yet focused, and despite not being in default work mode your instinctive faculties are sharpened; you are spurred by thirst and the desire to enjoy yourself.

The journey starts at the end

Accept what life offers you and try to drink from every cup. All wines should be tasted; some should only be sipped, but with others, drink the whole bottle. —Paolo Coehlo

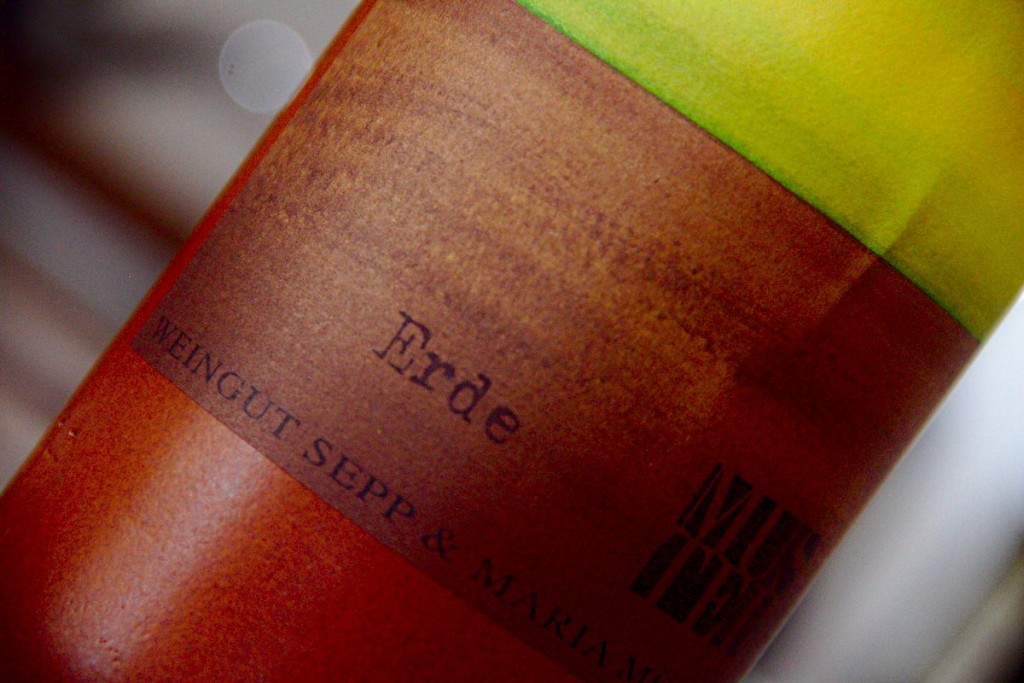

The other week I met a friend of a friend at Terroirs. I asked her if she was amenable to trying an unusual wine. She declared herself willing and so I ordered – and we drank – a bottle of Sepp Muster’s Erde from southern Styria in Austria. I can only describe the experience as beautiful, for the wine took us on a wonderful sense-ravishing journey. Initially, it detained our attention with its striking orange colour, inviting us into a nose hinting of orange blossom, elderflower, wild mint, golden plum and apricot skins. The wine had moved by the second glass, its palate revealing honeydew melon with delightful pickled ginger and dried cumin, then changing once more slowly becoming leaner and more reserved, impressing now on the stones and mineral salts (the opok showing through here). By the final glass the Erde was tightly wound, more intense and spicy, the minerals shooting through the fruits themselves. My companion and I looked at each other and simultaneously mouthed the word: “Wow”.

Such experiences mingle beautiful hilarity with clarity in a kind of epiphany. The wine exudes glamour, charisma, celebratory joyfulness. We owe it to ourselves (as well as to the vigneron and her wine) to be receptive. Increasingly, I try to experience wines more completely, by not insisting but rather sensing them, not itemising my impressions as if I were searching out a shopping list of qualities, but casting judgement aside, tasting inside out, exploring personality, viewing flaws as textural variations within the whole rather than diminishing faults. I want to dive into the internal story, engage with origin. I am into mutability and playfulness on occasions. I like simplicity and singularity, wine as haiku, the miniature of grace and purity. I like structure, but I don’t always need structure. Wilfulness is also fine. Energy, tension, cut and crunch. Juice gushing over my tongue. All this.

Suspending over-acute critical faculties is an important part of this receptiveness. My instincts are my real processors. If the wine possesses life then I am not above it, not grafting my preconceptions nor opinions onto it, not showering it with real or metaphorical points. For I know nothing except that which I know. When I’m tasting I need respond to the wine as the wine itself– to understand what it was intended for, be it juice for gulping, or a liquid vinified slowly and carefully in order to age gracefully. I should factor in other variables in my determinations, such as the weather, the calendar, my mood, whom was I tasting with.

The act of tasting places us in a necessarily artificial situation. Whilst I’m sure that oenologists do make wine to withstand critical scrutiny, many artisan wines were never intended to be mercilessly magnified in this fashion. Wines, real living wines, take their colour from the context. As mentioned, one’s perception and appreciation of wine (for example) varies considerably according to the person you are experiencing it with. There is one master of wine with whom I have never tasted a bottle that did not exhibit some technical flaw, as if the very act of dissection served to infect the very nature of the wine itself! Conversely, when I taste with certain people the wines always seem to sing. It is oddly as if the generosity of spirit and predisposition to find pleasure activates a life-force in the wine, whereas the deconstructive analytical tendency discovers a wine that is indeed the sum of all of its faults. Negativity is toxic. So is cultivated indifference. Positivity is the biodynamics of the spirit!

Wine does not have to be put into words or formulae

When you are open-minded you respond spontaneously. When I encountered my first natural wine twelve or so years ago in a Parisian wine bar I was shocked (in the best sense). The wine was primal and raw. It probably had high VA and doubtless a number of other jagged faults– but was it high, and too high for what? For my enjoyment of wine? Assuredly not. I knew nothing of the wine nor the grower, but I felt the difference, the ridiculous jolting energy, the fermented wildness in the glass and I still remember all this as if it were yesterday.

Yet, from chemical analysis to scoring, wine is presented as a “numbers game”. A grower such as Craig Hawkins harvests when he is happy with the taste of the grapes on the vine. Intuition and experience are his guides. His assessments are incorrect, apparently, because his tolerance for acidity is too high. At least according to one well-known wine writer. The numbers apparently don’t stack up, thus the wine is inherently wrong. And I’m wrong too because I love the wines and so are the tens and thousands of other consumers who seek out and drink Craig’s wines. For Craig read hundreds of vignerons who work according to their feelings instead of orthodoxy.

There is a lovely scene in Jonathan Nossiter’s Natural Resistance in the vineyard of La Stoppa, owned by Elena Pantaleoni, wherein we are invited to the table to enjoy the company of friends, family and work colleagues as they have lunch. As the meal progresses and the wine kicks in (it is a golden-hued skin contact wine that seems to capture and then radiate out the sunlight) the mood changes from intellectually passionate, to serious, to confidential, to teasing. We can see that wine is the catalyst for, and the background to, the discussion, the emptying bottles showing that the proof of pleasure truly is in the drinking.

Elena’s niece (who is studying oenology) remarks that all they teach you at wine college is to use this chemical or that. They never teach you history, culture…Wine is a scientific problem to be solved, it exists as a series of equations and finite options, and viewed as set transformations achieving settled objectives. The divide between families and friends drinking the fruits of the vineyard that they are sitting in and enjoying freewheeling discussions about wine (the politics, the culture, the people, the actuality of the wine) and the gospel of narrow chemical prescriptions as preached by wine schools could not be wider.

Asseverating that wine is surely made to be enjoyed, to bring people together around a table in the jolliest fashion, seems unnecessary, yet criticism, by constantly arbitrating on personal taste, has (over)colonised our enjoyment of the product. Where wine is appreciated as an artisan product, where deliciousness is prized, where drinking good wine is the catalyst to bright conversation, the seasoning for food, the foundation for camaraderie and the instigator of pleasure, loosening inhibitions and kindling the imagination, then there is indeed truth in wine, albeit you never see it listed in the ingredients on the label.

The final word should go to Christopher Hitchens, a man of many words and almost as much liquor. He bring together the Dionysian, aesthetic and humanistic reasons for drinking.

Alcohol makes other people less tedious, and food less bland, and can help provide what the Greeks called entheos, or the slight buzz of inspiration when reading or writing. The only worthwhile miracle in the New Testament—the transmutation of water into wine during the wedding at Cana—is a tribute to the persistence of Hellenism in an otherwise austere Judaea. The same applies to the seder at Passover, which is obviously modelled on the Platonic symposium: questions are asked (especially of the young) while wine is circulated. No better form of sodality has ever been devised: at Oxford one was positively expected to take wine during tutorials. The tongue must be untied. It’s not a coincidence that Omar Khayyam, rebuking and ridiculing the stone-faced Iranian mullahs of his time, pointed to the value of the grape as a mockery of their joyless and sterile regime. Visiting today’s Iran, I was delighted to find that citizens made a point of defying the clerical ban on booze, keeping it in their homes for visitors even if they didn’t particularly take to it themselves, and bootlegging it with great brio and ingenuity. These small revolutions affirm the human. —Christopher Hitchens, Hitch-22: A Memoir

Affirm the human indeed. It’s nice to abandon logic (to be an uncritic, as it were) and the habit of mind that would “murder to dissect” (to quote Wordsworth) wine and to go with one’s tastes and with what one feels. So many of our responses are mediated through the thick gauze of criticism that we utterly neglect the hedonic, sensuous appeal of the wines in favour of brute diagnostics.

There are faults and faults; it is wise not to be absolutist in these matters and indulge in a tyranny of fault-finding wherein anything that deviates from the designated cleanliness/godliness norm must naturally trigger a disparaging response. We all have our tolerances. Some of the wines that some people laud to the heavens I find undrinkable for so many reasons and I find it reassuring that the opposite is also the case!

Whilst we can merrily agree to disagree about taste it is perhaps unwise to describe– and damn- any and all wines at a wine tasting as unpleasant (because you “believe” it must be so) so as to create an ideological platform from which to attack low/non-intervention wines – when you are in absentia. It is not just absence that makes the mind grow more cynical; we have to ask ourselves whether this is a fair summary or even an approximate depiction of the truth, or simply an opinion cultivated by some critics pleased to flaunt a professional contrarianism. It is the argument used by people who have philosophical difficulty with the mere concept that good wines might be successfully made in such a fashion – resulting in a critical approach that is akin playing the man rather than the ball. As Keats wrote aphoristically in a letter to his friend John Hamilton Reynolds, “axioms in philosophy are not axioms until they are proved upon our pulses.” Opinions, even when they are couched as if they are statements of unvarnished truth, are still opinions, for all that. In the wine world where drinking and enjoyment are paramount these axioms are indeed proved upon our pulses.

Elevating the discourse above the notion of wines as functional microbiological and chemical transformations into a more poetic narrative about vines, place, people, life and love and much more, brings us closer to the real purpose of wine. Respecting this story shows a desire to form a relationship with the wine, otherwise it becomes merely a vehicle for different transactions, a highly processed product with a finite commercial purpose.

Vignerons like Kelley Fox are part of a family of unique storytellers. Wine is her terroir songlines.

My wines are the two vineyards (the grammar is intentional-they are those vineyards), Maresh and Momtazi. Both volcanic soils. I love working with the young volcano energy here. My approach comes from a conscious intention of emptiness- a state of no-self. I wrote somewhere, that I am not Pygmalion. I have exactly zero goals for the wines other than strong transmission of the place and the year, etc. The wines are themselves and are free. I can write about them like this, because these things have nothing to do with me.

“Wine…changing even as we taste it, delivers a message with meaning only in our response. If we are in the right key when we receive it, our eyes will shine and we shall radiate pleasure,” wrote Gerald Asher in The Pleasures of Wine. Yet someone will always put the emptiness into a straitjacket, pour the wine into a mould and not take time to listen the story. Tasting is an opportunity to learn for those who are open-minded, drinking wine an opportunity to experience pleasure for those who are truly tuned in to that possibility.