Day Two

Gentle advice for those who talk about natural wine

This much I know: always give a talk whilst suffering from mild jet lag, the equivalent state of gentle inebriation that allows your words to float away from you like balloons.

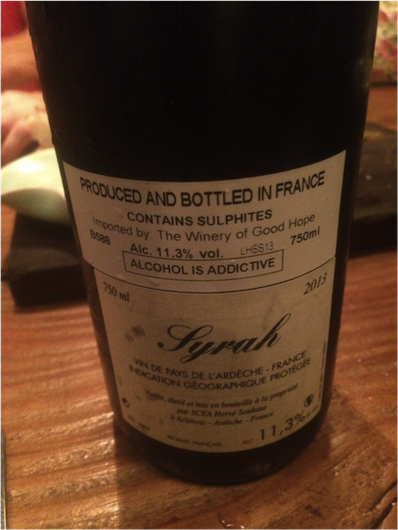

Caroline’s Wine Shop in Cape Town, in conjunction with Alex Dale wearing his importer and wine distributor hat, hosted its second “Natural Wine Tasting,” which was ostensibly the main reason for my visit to South Africa. A small group of South African growers who work in a less interventionist vein were exhibiting their wines, whilst other tables featured a selection of wines from vin nature heroes and groundbreakers such as Jean Foillard, Yves Souhaut, Pierre Breton, René Mosse and Thierry Germain.

I was there to pour and chat about the wines and give a short speech to help to break down barriers surrounding (what is perceived as) a contentious subject. You would like to believe that the truth of these matters is pure and simple. Alas, semantics, personal taste and critical posturing impede clear understanding. Plainly, some are exercised by the very notion of natural wine, and find it a fundamentally alien concept. An unnatural one, in fact. We can ignore this or try to educate people to open their minds at the very least and not to accept some of the wilder generalisations one reads about the growers, their wines and even the people who drink the wines. The wines are not a secret; they may or may not have a reputation, but ultimately they are exposed in the court of public opinion. People will drink them, or they won’t.

All discourse should, one hopes, be informed by the spirit of generosity. Wine, after all, is a subject that should bring folks together, not leave a bitter taste in their mouths. Show the love and welcome them into your world rather than present the binary-opposition universe of false dichotomies, wrongs and inalienable truths. None of us have all the answers, albeit that some people might proffer rigid professional opinions that suggest that they do. I like to drink what I like to drink, you like to drink what you like to drink; somewhere in the middle are the wines that we would be happy to share a bottle of with each other. That’s as it should be; wine as a social lubricant, making people happy, the inclusive rather than the excluded middle.

Remind your audience that you are all on a journey – each journey is relative to who you are, where you start, how far you wish to go, and whom you are influenced by. Your opinions about wine will change as you yourself change. Wines transform. Tastes change. Theories evolve. Wine is not a theory, though, it is an actuality. It is a drink that has been painstakingly crafted, shaped by innumerable decisions in the vineyard and the winery. We need to bear these processes in mind before we pass glib judgement.

Celebrate the differences not only between wines that are made more naturally and those made with chemical interventions, but amongst the wines that are deemed to be natural themselves. But why is this wine different to that? What is it that shapes the wine? Process. A fish will be different if it is steamed or roasted or grilled or eaten raw. And will taste different if we serve it with a rich creamy sauce or season it with salt and pepper or spice. Chicken or lamb or beef tastes different according to what it was fed or grazed on. If a vine grows in this soil or that, enjoys x or y sunshine per year, if you ferment in a small or large tank, use stems or take them off, age it in stainless steel or wood (new or old) or cement, if you add this yeast or that, if the temperature is cold or warm or controlled or not, if the fermentation container has air or the wine is protected by carbon dioxide. Natural wines witness a number of transformations but those who make natural wines are seeking to capture the simple essence of the fruit, the vintage and the terroir. Much wine is a construct – terroir is irrelevant, grape quality is less important than that the process is rigorously adhered to in order to deliver a clean product that conforms to objective standards. Many of the wines that we love have been rejected by tasting panels whose raisin d’être is to protect the commercial reputation of a region or country rather than understand why the wine is the way it is. This means that if you choose not to filter, or sulphur or that you work oxidatively (for example) your wine may well be excommunicated. I am no less a writer or a speaker for having different opinions to the majority, but this winemaker is considered less of winemaker for expressing his or her way of doing things. So much for diversity.

Don’t be afraid of the word natural. “Nothing in life is to be feared; it is to be understood” (Marie Curie). Natural is a word – as such, it doesn’t bite. One doesn’t need to define or defend it. Natural is a fluid rather than fixed term, implying towards a natural methodology. It is also an inclusive rather than exclusive term, not a few people in a club, but suggesting a general philosophical approach towards making wine. If you’ve got the grapes (literally and figuratively speaking) you can do it. Different growers will have their different ideas where they might be on the spectrum, they may even disavow the term, but follow the practice, but most of the time they are pragmatically getting on with making wine rather than agonising about what to call it. It seems logical to them to work naturally; it is the way they live their lives and part of what they believe. If biodynamics is the holistic/wholehearted version of organic viticulture, then natural winemaking is its logical extension in the winery, a course of action motivated by a desire not to get in the way of the wine. The process is not about succeeding in making something precise, it is the very nature of the journey and the nature of the nurturing – so to speak. The wine will have its own life eventually, be poured and consumed thirstily by some, or pored over and criticised to death by others.

Yes, the expression natural wine suggests putting the vineyard and the wine ahead as opposed to the deterministic results-based approach of the oenologist qua oenologist. It is a part-empirical, part-intuitive approach to process and transformation. Because wine is perceived as having value, it is consequently exposed to scientific and hierarchical evaluation. Remind them of all the natural unprocessed things they eat and drink in their world, how simple transformations may be and yet the food and drink can be so delicious – be it unpasteurised cheese, sourdough bread, ales and cider or raw fish. All these have a pure function, which is to nourish us – yet I have never rated a loaf of bread out of 100 or compared tuna sashimi with mackerel. You might as well say that one tree is better than another or this sunset is better than that.

Remind them also what is denatured and processed – how the food lacks mineral sustenance since the advent of invasive chemical-based farming. Critics question the authenticity of natural wine because some of the wines do not conform to what they believe wines should taste like. They question every aspect of the winemaking, because they see wine as a means to a commercial end. Perhaps we should pose our own questions.

Firstly, do we need wine at all if it means plundering natural resources and creating desert monocultures simply in order to make cheap chemical grape juice? Is adding chemicals to wine not tantamount to saying that the wine could not exist other than in a chemically stable environment? What does that say about the quality of the wine? If wine is so denatured by addition and manipulation then is not origin irrelevant? And, by that logic, appellation also? Why is consistency more valued than singularity? Why is making wine to a fixed recipe always seen as the correct method?

Many natural vignerons trained in winemaking schools where they learned method, order and structure. They were not allowed, however, to question the received wisdom. They were told to farm with chemicals. They were instructed to make wine in a specific way. As one grower says: “Learning is everything they didn’t teach you at school. It’s about being free to think for yourself.”

Talk about terroir – it is a primal force in their lives. When we speak to growers we surely assume that they are proud for their wines to represent the best of their country, their region, their farms and themselves – given this why would you obfuscate the sense of origin through excessive intervention?

Winemaking is too often viewed as a necessary corrective rather than a sympathetic accompaniment. Like giving birth – it might be the most natural process in the world, rather than an illness or a medical condition. If all is well with the patient (the vines and the wine in this scenario) then the vigneron should only act as the midwife. If complications arise then she must be the doctor or the surgeon, intervening to help the wine through its difficult labour.

Natural winemaking then is bringing forth information about the vineyard, the soil and the microclimate and the endemic yeast populations. The approach sustains, supports, accompanies and channels. The wine is the simple beauty-in-truth that is crafted anew every year according to the raw dictates of nature rather than the recipe-led approach which views grapes as the precursor of winemaking correction and enhancement.

Enjoy your wine. You should be happy to be drink it and feel no need to defend it.

Risk reaps rewards. Humankind progresses not in increments, but in leaps and bounds.

Natural wines can and will surprise you. For example, they may be fresh and light on their feet, yet many of them age wonderfully well, conserving their intrinsic shapeliness. The protection is not attached to the outside – a thick veil of sulphur, an impenetrable grid of tannins, the armour of oak, but resides in the very health of the juice itself. The natural structure is within. Stored correctly they can last for many days even after being opened. Even if the rulebook tells you the opposite. It seems that there are so many microbiological transformations that simply caricaturing (or summarising) the end product shows a failure to engage with something living.

The world of natural wine and natural vignerons has never stood still, but turns more quickly because it is not weighed down by expectations and regulations. When wings are not clipped growers can fly, are free to explore their own space and make the wines that they feel comfortable with.

A humble wine taster takes prescriptive wine theory with a pinch of salt, casts aide preconceptions and endeavours to taste in the round. We’ve been inculcated to tick boxes, to judge against a norm, to look for what is wrong. We must recognise that wine is more than the sum of its perceived faults. Purity is never pure. Flaws are the distinguishing marks of an individual wine. That wine may be a liquid that can evoke an emotional reaction and does not require anatomical dissection. Ask them to respect wine for what it is and for what the grower may be trying to achieve, to see through falsity and meretriciousness and to gauge whether the wine is alive, vital, mutable and provocative.

Wine is composed of volatile aromatic properties. If they help the wine to come to life by forming an unlikely bridge to terroir, they are the map on which the story of the vintage is drawn. This is an original hand-written map, not a facsimile.

Natural wine makes us re-examine the so-called certainties that we were all inculcated to believe. It leads us to investigate how wine is made from scratch. How important it is that the vineyard be given the wherewithal to produce the grapes that form the building blocks for the wine. How the vinification should respect the nature of the grapes and help to capture the singular sensation of terroir or the unique quality of the fruit. What we have as a result is wine of different shapes and sizes. It comes from different places and is made by different people – this is the diversity of nature and human nature.

The Natural Wine Tasting

I was positioned behind a table of Loire wines stroking my imaginary René Mosse beard, grinning cheekily like Pierre Breton and being gently jovial like Thierry Germain.

We start with Thierry’s Saumur Blanc Insolite from vines that have plunged their roots deep into the chalky-limestone soils. One might describe them as sunlight held together by water pierced by stone. There is incredible vitality on the palate with perfect balancing acidity. The wine is paean to Chenin Blanc, a snapdragon on an anvil, and drinking it will give your goosebumps goosebumps.

Mosse’s Chenins are a different proposition. They are broader, more lactic and honeyed. The equivalent of a Cornish cream tea with scones. The Savennières has more intense, almost volcanic quality in the texture of the wine with searching length and smokiness on the finish.

The Breton Vouvray La Dilettante is tenderness embodied, bonny and bright with primary aromas of quince and honeydew supported by a ripple of quenching lime acidity.

The reds showed equally well. From Breton there was the buoyant Trinch!, cheerfully purple and succulent (not a tasting term I use often), whilst the Chinon Beaumont, from a vineyard with 50-year-old-plus Cabernet Franc vines, felt deeper and more earthbound with thick-skinned dark fruit and a dusting of herbs. Thierry’s baby Saumur-Champigny had a lilting freshness and pure energy – violets and irises rose from the glass, whilst the tongue greeted a crisp crack of currant fruit. No sulphur on this wine at all.

No-chemical wines. Nothing here to frighten the horses or agitate even the most of crustafarian of critics. For natural wine is not an idea, a straw man to set up and knock down for the sake of argument, but something real and crafted. Every wine is different; some are wonderful, some are rubbish – according to your taste or point of view. When they hit the mark they are so delicious; it was noticeable that wherever I went in South Africa to taste and drink, the low/no intervention wines were always the first bottles to be drained.

Postscript: After the Natural Wine Tasting we went to the Pot Luck Club, a super cool restaurant on the top floor of a converted biscuit mill in the Woodstock area of Cape Town. The brainchild of Luke Dale-Roberts, who also works at the world-renowned Test Kitchen, this is a vibrant with equally vibrant fusion food.