Boy number twenty unable to define a wine!

“Girl number twenty unable to define a horse!” said Mr. Gradgrind, for the general behoof of all the little pitchers. “Girl number twenty possessed of no facts, in reference to one of the commonest of animals! Some boy’s definition of a horse. Bitzer, yours.”

“Quadruped. Graminivorous. Forty teeth, namely twenty-four grinders, four eye-teeth, and twelve incisive. Sheds coat in the spring; in marshy countries, sheds hoofs, too. Hoofs hard, but requiring to be shod with iron. Age known by marks in mouth.” – Hard Times, Charles Dickens.

This is not an important wine article. In fact, let’s be serious, wine articles are rarely important. But there are plenty of itches we need to scratch and some are in public. This is to do with my dislike of tasting notes, especially the more orotund, whimsical and fulsome examples. (Disclaimer: I am not a killjoy)

I, as many others did, learned at the font of a well-known wine school, whose gradgrinding methodology sucked the very protoplasm of joy out of the wine tasting experience. We learned that wine was the sum total of its parts of smell and taste (and sight), and that each part could be broken down into smaller parts, and still smaller parts, in order to be scientifically apprehended. And, as humans, we could aspire to be sheer instruments of apprehension, our senses honed in order to be imprinted on. We would have tasting negative capability. We could be less human, so we would be more accurate. I exaggerate a mite, but they certainly inculcated an idea of what was correct/incorrect into our responses to wine.

And so, a tasting note would be constructed. Not written, mind you, but constructed. But even a single word is itself a clunky thing. And a group of words bolted together, clunkier still. Even the Bitzer-est amongst tasters, needs to select one word over another to carry the descriptive load. What is essentially an objective exercise, soon becomes riddled with subjective choices.

You can tell who has attended wine courses and absorbed good “tasting note practice” by the kind of autonomic approach to tasting notes. Some produce notes with the ease of athletes trained to do a repetitive task. Some love the format as its structure allows them just enough wriggle-room to insert something graphic or poetic into the customary strait-laced jargon and thus show off their individual palate, just as dwellers in a row of identical terraced houses will all paint their doors different colours as an assertion of their respective individuality.

Just as Milton moved through the gears from translating to pastoral and classic to the freedom of the “Miltonic” epic, tasting note neophytes apprentice as angelic robo-recorders before becoming full-fledged creative soloists.

With confidence and cockiness, tasting notes can be pushed further and further into loftier realms. The rainbow must be spun, the almsbasket of words ransacked for rare descriptors, the most exotic fruits plucked from the air or the bush, baffling similes and tortuous metaphors incanted in the name of originality. We are all William Blakes in our cups, only without the songs of innocence and with enough experience that shows that a little learning can be a dangerous thing. Yes, these are the tasting notes that are heavily fined with ego.

I am not going to talk about wine as industrial fermented grape juice. Wine, roughly speaking, is the amalgam of terroir, farming, transformation and time. It is as complex as the myriad root systems that delve and connect into the underground web of microfauna and flora. For all our knowledge of scientific process, we know very little of what makes a wine in nature, yet we are happy to pontificate about the end result as if it can be so easily captured in a few “choice” words.

Wine doesn’t exist to kowtow to the ego of the taster desperate to show off their verbal gymnastic/contortion skills. Or does it? What about freedom of speech, after all? Why should not these wine prestidigi-tasters have the opportunity to parade their word-orgasms? Why not allow a little verbal ostentatiousness into the sullen and mundane world? Because it is annoying, and not a little egocentric. So many tasting notes are not about trying to penetrate to the heart and soul of the wine, nor are they about communicating an experience of a bottle or a glass of wine with others. They purport to parade the genius of the tasters above the wine, allowing them to revel in their sense of cleverness. The orotund tasting note doesn’t bring others closer to the wine, because it is couched in a way that doesn’t attempt the describe the wine in question. It is that analogy in the back pocket, buffed and rebuffed, polished to glittering precision and then released to the applause of the attendees of the masked ball.

Your tasting note is both good and original; but the part that is good is not original, and the part that is original is not good.

And if the tasting note purports to be serious then it is ridiculous, and if it is intended as a joke, then it is a tired parody of one.

Let’s look at different kinds of tasting notes. I have referred to The Bitzer, that pure neutrality of fact, that calibrated nothingness, that leaves us none-the-wiser in terms of what the wine is about. There are other tasting note archetypes:

Of cucumbers and cola

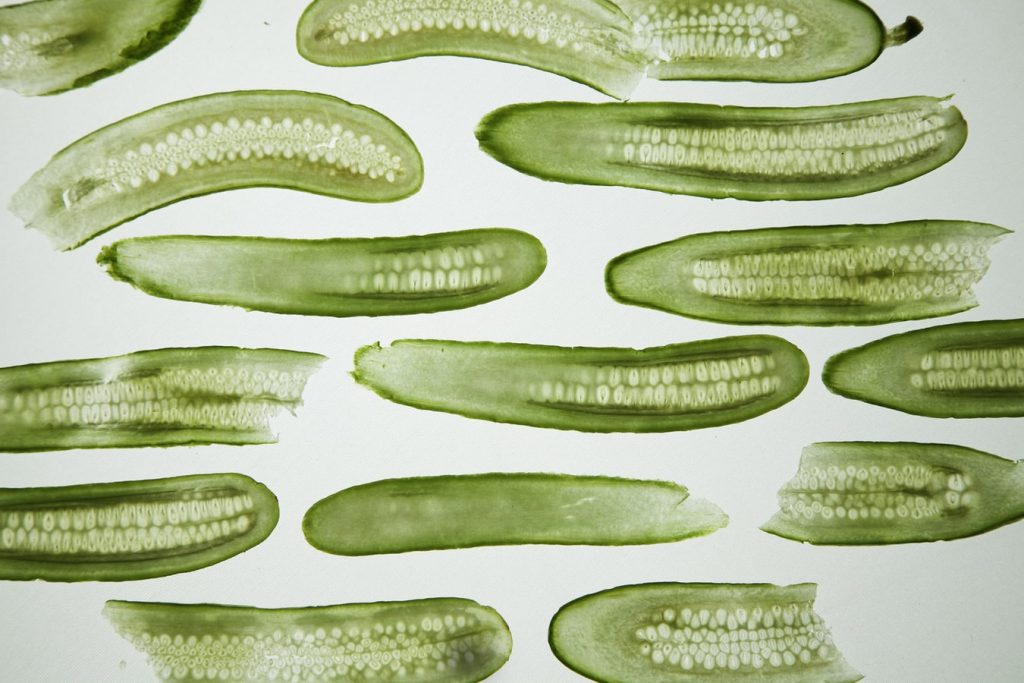

I once read this simple statement: “It tastes of cucumber”

Bearing in mind the fact that cucumbers don’t grow on vines, what can we say about this? That it is odd that the primary aroma or flavour would remind us of cucumber? It is not beyond the bounds to think that a cool refreshing wine might conjure associations (as in the kinetic sense of coolness) similar to cucumber, it is something else to distil the entire essence of the wine into the notion of a cucumber. On the other hand, our brains work in very particular ways, and if our imagination is wandering down a strange back alleyway in the neural network, it is more than possible that we may discover an extraordinary buried association. And if that neuro-chemical association is so powerful that smelling instantly bring the memory of cucumber into the part of the brain that processes our instant responses, then there is neurological basis for this comparison. There are more cucumbers in heaven and earth…

If we make an allowance for cucumbers, then there are, of course, an infinite number of others associations knocking around in our grey/pink matter waiting to be triggered. If someone says that a wine tastes of coca cola, what then? Is that the unkindest cut of all that the taste makes them think of coke, or is it, in fact, quite a common occurrence in that many tasters experience and talk about flavours of cola (leaves, cubes, coke) in wines. However much it horrifies me to think that wine could be thought to taste like coke, there are wine styles which are the result of a combination of ripe fruit and confected winemaking and are more than reminiscent of cola (in a generic sense) and even certain brands of cola (in a specific sense to certain individuals who have consumed that brand of cola).

For all that, if a wine that is ultimately the result of tectonic plates shifting, oceans falling, thousands of years of geology, hundreds of years of agriculture, the lifetime experience of a farmer and the magical microbiological transformation of grapes into sophisticated wine, can be described simple as a “cola cube”, then something is wrong!

Is that any more ridiculous than when I talk about notes of cinnamon or ginger? Or someone else steel, or horse manure.

Wines do have identifiable chemical and microbiological compounds that can be easily detected by humans: rotundone (pepper) sotolon (curry powder), to name but two, and these will give rise to powerful associations amongst certain tasters as the smells/tastes activate certain receptors in the brain. And there are others and we ourselves can access hundreds and thousands of taste memories which will provide the raw material for our tasting notes. Easily-accessed memories are not a reliable guide to what a wine tastes like; they are merely rough equivalences, like saying: “This sort of reminds me of…” It is easier to compress a comparison into a Jolly Rancher or a cola cube than to dig deeper and find the right words to describe what a wine is really about.

Having said that a tasting note is a balance of the quantitative and the qualitative. The association is one element of the whole and the real part of the wine qua wine is each property that makes it real and vinous. The journey to find your inner cucumber is something separate and very personal and you have to decide whether it is intrinsic to the wine or just that you are wired for weird. The properties of rotundone, for example, are part of the wine – in that they can be measured and accounted for – and the perception of them can be included in tasting notes. A more complex tasting note would feature a balance between the extrinsic and intrinsic elements of the wine, but that requires a sensitive approach that can merge a certain methodology with the ability to describe personal impressions in such a way that it doesn’t seem like an extended trip.

“Schildnechtia”

Taffeta phrases, silken terms precise,

Three-piled hyperboles, spruce affectation,

Figures pedantical – William Shakespeare

The word-piling approach, where the tasting note takes on a life of its own and screams into a vortex. As the momentum builds, new verbal passengers board the sentence and move around the clattering carriage, clauses give way to sub clauses; random commas, colons and semi-colons are deployed as safety harnesses; crafty rhetorical flourishes creep in; the groaning fruit trolley appears laden with almost infinite choice – and before you know it – you are being overwhelmed with verbiage, and plastered with adjectives and adverbs. Yet despite all the careering and careening and verbal cocktail-shaking, you somehow remain on the tracks. And then you go for a lie down.

Schildnechtians will leave no stone unturned, no choice word unused. Nothing is unwrung, the tasting note squeezed to complete its wrinkled servitude. Most professional notes go here by the way, imbuing even the simplest wines with complex architectonic linguistic framework, as if to say unofficially: more is more. The more berries I can fling at this wine, the better, the more the berrier. QED. We can all dance around the mulberry/boysenberry bush of that sentiment.

Analogy in a digital world

The far-fetched analogy, like a metaphysical conceit from John Donne or George Herbert involving compasses or pulleys, dragging the idea kicking and screaming back into the centre of the poem, or, in this case, the ludicrous extended wine metaphor, whose sheer fancifulness makes us smile and by smiling we partly concede the brilliance of its stupidity. Example: “This wine is like two honeybees copulating in front of a sunset in Sherwood Forest.” Note that the more detailed and offbeat the circumstantial element of the metaphor is, the more brilliant the overall effect. Or, is it more what Pooh-Bah said: “merely corroborative detail, intended to give artistic verisimilitude to an otherwise bald and unconvincing narrative.” Yes, in reality, the far-fetched analogy is a total brain fart, but we occasionally applaud its execution. An Italian producer once expressed total bewilderment regarding some tasting note for his wine. “Wine is made from grapes. How is that about grapes?” Well, we now know that AOP stands for Appallingly Overcooked Platitudes.

There is a subset of the far-fetched analogy which is one with added shock – and maybe some awe. Usually, someone who had dieted on a surfeit of Henry Miller, Catcher in the Rye and William Burroughs and wants to visit something unpleasantly phantasmagorical from their playfully corrupt imagination on the rest of us dumb innocents.

Nothing can come of nothing

The… “it could be anything” tasting note. Often applied to the back label of a bottle, conversely also given to us by growers when they “fill in” our technical spec sheet requests. The latter is the middle finger and that finger is telling us not to even attempt to circumscribe their beautiful wine with facile words. One grower actually used to write in the tasting note box – “it’s good.”

“Words strain,

Crack and sometimes break, under the burden,

Under the tension, slip, slide, perish,

Decay with imprecision, will not stay in place,

Will not stay still” – T.S Eliot

Accepted!

Back label tasting notes are probably zen-computer generated as their all-purpose milquetoastiness that makes one’s eyes glaze over. It is arguable that you could ever finish reading one. There is a strange beauty in a collection of words that satisfies the carnivorous, chicken-eating vegetarian who has indiscriminately purchased a bottle of red, white, other, yeast-flavoured grape juice that was manufactured to be all things to all people. And so, the tasting note should be purposely vague, multi-applicable, endlessly recyclable.

There is room for personality and originality in tasting notes without peacocking. The first thing though is to try to sublimate that ego which wants to wrestle the wine to the floor, put into a chokehold and squeeze the essential meaning out of it. Wine is not a conundrum to be solved or a code or something that requires to be put in a box to justify its existence. It is a fluid, living, energetic thing, changing (when it is good) and evolving, one thing for the moment experienced, another for the moment recollected later in tranquillity. The person who listens to the beat of wine, who sniffs deeply but not deeply, who feels and tries to reflect before coming to a definitive tasting note, is the one who is most sensitive to what the wine has to offer and doesn’t show off.

My intolerance for the tasting notes of others is nothing compared to my intolerance for my own efforts in this regard. I specialise in total incoherence rather than practice any of the abovementioned rhetorical tropes, but I find that every time I describe a wine in terms of a fruit or vegetable or something else, or an overwrought combination thereof, that I have just nailed another butterfly to a wheel. (Metaphorically speaking!). I prefer to abide by the (Dr) Johnsonian: Read over your compositions, and wherever you meet with a passage which you think is particularly fine, strike it out. I don’t want to be fancy and I don’t want to be a soul-dead Bitzer.

My real tasting notes are lodged in some dusty corner of my brain, unformed thoughts and feelings waiting to be summoned into life. The sense of what a beautiful wine is way more vital than the mental energy used to construct the words to be able to frame it – there’s a disconnect which I am uncomfortable to resolve. Now, my notes are floaty-verbal (let the air take them), or if I submit them to social media, the tasting notes are reduced to uncultured apostrophic grunted “wows”. Yes, I have reverted to atavistic discourse.

Which is not to say that I wouldn’t love to read some lovely tasting notes.

Imagine, for moment, a tasting note being confined to seventeen syllables, and that confinement something utterly succinct, tactile and pellucid? Pure nuggets of emotion. Pure to the zenth degree. A poem that is a gentle ripple in space/time and then instantly forgotten. And no less valid than describing a wine as a boysenberry or a dingleberry, or a cucumber, or a copulating bee. Stand by for my first tasting note haiku…

I am working on a new virtual reality system where instead of a tasting note, readers are taken to a place, but in my system it will be an abbey church or temple. Cluny in its splendour compared to the Cistercian purity of the white abbey, Pontigny (near Chablis). Dark El Escorial or Bom Jésus (if you’ve never been to the latter, in Northern Portugal, don’t, it’s way too scary). I’ve also a nice line in Hindu and Buddhist temples and shrines lined up. Pairing wines in this way will surely provide enlightenment in a way no TN ever could. Are you in on this, Doug?

That could work, David. I am guessing that musical correspondences would make the best TNs. Live musical renderings too, as that corresponds with the fact that wine is different from day to day, bottle to bottle.