Attitudes to natural wine are similar to hard-wired attitudes towards Brexit. People don’t want to listen to substantive and nuanced arguments or to understand that its increasing popularity in historical attitudes to culture and farming. To followers of the wines, espousing a natural wine credo is an assertion of cultural identity. Natural wine has become synonymous with caring about the environment and valuing provenance and authenticity (another buzzword). By positioning itself against the corporate, the industrial, the commercial imperative, the artisan nature of the winemaking enterprise has an implied political status. Those who oppose the idea (or actuality) of natural wine do so for a variety of reasons. The chief amongst them is the dislike of the word “natural”, which is viewed either a meaningless term (how can wine – as a manmade product – be natural?) or an unfairly morally-loaded one (implying that all wine not deemed natural must ipso facto be unnatural). Some opinion-formers, journalists and people who work in the wine industry also believe (often without evidence) that natural wines, by their nature are naturally flawed. However we define our terms. or set our standards, ultimately the wines are the wines after all, made by individuals and the result of a thousand decisions (to coin a phrase) as well as uncontrollable circumstance. Each wine deserves to be drunk on its merit with an open mind as well as an open heart, not to be viewed as the product of ideology.

By positioning itself against the corporate, the industrial, the commercial imperative, the artisan nature of the winemaking enterprise has an implied political status.

Many people talk about wine as if it were merely a commodity. I am fond of quoting an English MW who declared solemnly to me that wine was “a product for a purpose.” Commodities are necessarily measured against normative values, so the wine is always deemed good or bad, great or awful, fulfils a useful function or has no commercial relevance. Our need to judge is rooted in the desire for social acceptance, to be part of a peer taste group. We can go to courses which teach you how to taste wine, what to look for and how to measure quality. We can read illuminating journalism or buy books about the subject. Whilst there are few who would deny that taste is personal, there are rules and frameworks by which good taste may be measured. Rarely, though, is the human element in all this mentioned—those special qualities that really matter for a person to taste deeply: intuition, empathy, openness, and a capacity not to over-deconstruct wine into its component taste atoms, but rather the ability to reimagine the wine as an energetic whole.

We are given certain equipment to help us taste, the formal wine language, the signposts, the rigid framework into which we are meant to pour our impressions. What is the purpose of this? Is this to enable us to communicate what we may taste by creating a common idiom, and, if so, is not the effect to reduce our impressions of wine to the broadest of brush strokes? Where do natural wines fit into this formulaic scheme? With their oft-changing aromas and flavours, many may fall outside the classic taste spectrum and may be dismissed by tasters unfamiliar with the style (or who are looking for something classical that they will not find). It is often not that they are faulty – a common assumption amongst classic tasters – but that they are analogue wines, if you like, in a digital world?

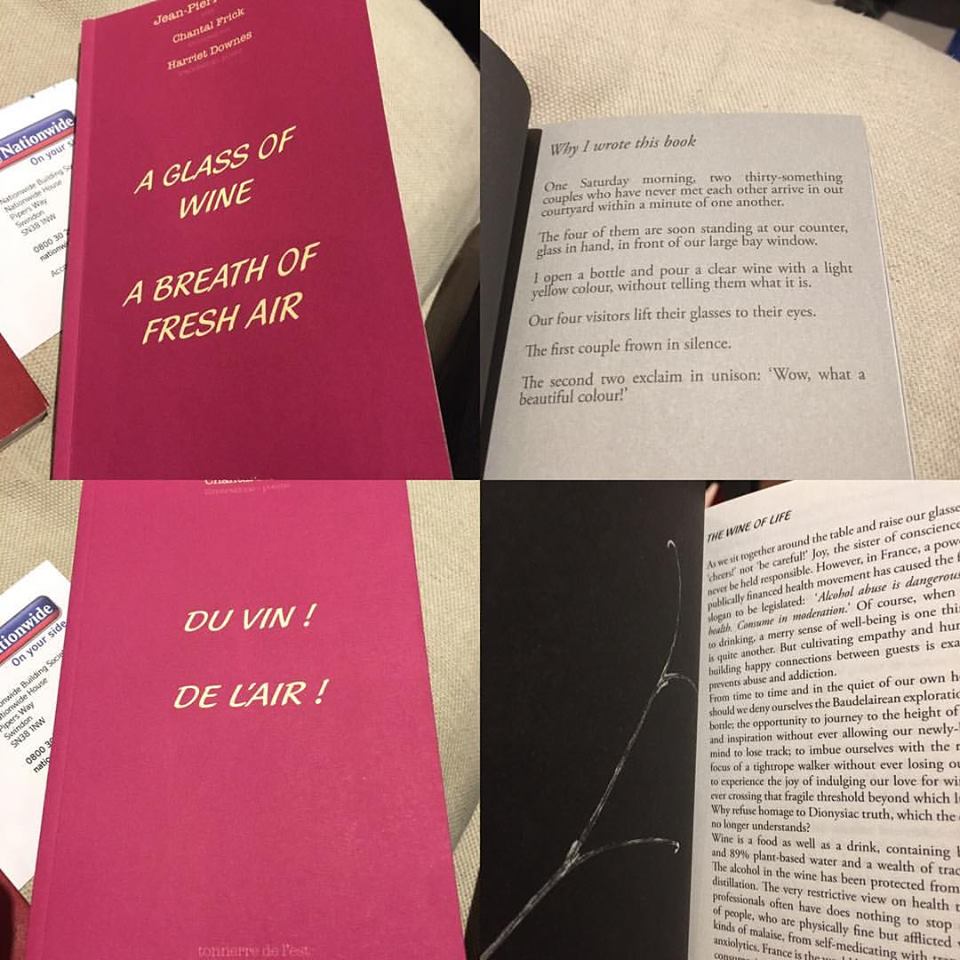

Jean-Pierre Frick begins his mini-thesis Du Vin de l’Air by describing two extreme types of taster: the academic and the adventurer. The academic, or professional, deconstructs wines on the basis of acquired knowledge. For them tasting is a matter of professional decorum, since they are tasting not just for themselves, but for knowledge itself, a knowledge that will be codified and organised and brought to bear at a later date. The adventurer, meanwhile, is intuitive; he or she prefers to sense the wine rather than judge it right or wrong. Normative values do not apply – the here-and-now is what matters; the very experience of tasting which excites the imagination and arouses the emotions.

For a further exploration of this subject, head HERE.

Taste and tasting are something we don’t talk about much when the teaching of wine trades almost exclusively in certainties. The historical and cultural context of wine is also ignored in favour of science. Uncoupled from both the context and our emotions, our attitude to wines becomes necessarily two-dimensional, almost functional.

Wine Culture, Winemaking

Certain wines have been prized throughout history; the wines from a particular region or even a village may have acquired a certain reputation for one reason or another and would be traded (and therefore have perceived value) or drunk by nobility. Before wine was a commercial commodity, it was simply a drink for the table. Not just special occasions, but for thirst and for food. In an agrarian society (and most societies were), many families would own or tend vines and make their own wines. They were farmers, not winemakers, there was no audience, no critics nor judges to calculate the responses of, and the wine travelled no further than from the vine to the cellar to the table.

It is often not that they are faulty – a common assumption amongst classic tasters – but that they are analogue wines, if you like, in a digital world?

Thousands of years ago in Georgia a culture was created around wine or rather wine was subsumed into every aspect of Georgian culture. It became an integral part of hospitality, ingrained into the very spirit of the country, and indeed was strengthened and perpetuated by the great monasteries. Wine assumed both a real and a sacramental role. For all that, the winemaking tended to be simple as all ancient winemaking was – whole berries placed into underground clay pots – skins, stems and pips – the wine fermenting with its marc (cha-cha), and remaining in the subterranean vessels until needed. Wine was sustenance, naturally grown, naturally made. As God and nature intended.

Things began to change with industrial revolution, a rising population that needed to be fed and a consequent push towards greater productivity, which led to the industrialisation of farming. After the war in Europe many left the land for the city, skills were lost, smallholdings were subsumed into the greater monoculture. Wine was something that could be made on a much larger scale to supply emergent markets. Chemical fertilisers, herbicides and pesticides became easily available. The winemaking also changed with yeasts and enzymes, and all sorts of chemical and biological agents that would ensure consistent results.

The result of this was vineyards devoid of microbial life, barren monocultures. Given this, oenological intervention became even more essential with techniques such as cold stabilisation, super-controlled ferments, inoculation, clarification agents, and epic additions of sulphur dioxide, all-in-all denaturing the wine as far as possible to ensure maximum stability. This was the vicious circle; grapes were the precursor for the process rather than being the vital element with the process respecting that.

The lack of productivity and fertility in the soils was something that concerned a lot of farmers. The first step was to restore life to the soil; only then would the preconditions be achieved in order to create a balanced environment for the vine to flourish. Enter Steiner, although his lectures and writings were not targeted at vine-growing, they still had applications and specific remedies and provided a philosophical framework for farmers to work within.

To be continued…

Stay tuned for Part Two, coming soon!

*

Interested in finding more about what’s sweet? Contact us directly:

shop@lescaves.co.uk | sales@lescaves.co.uk | 01483 538820

Spot on! It’s a tragedy that now we also have “label drinkers” among people who prefer natural wine – or rather the people who drink natural wine just because it boosts their image. Wine should first and foremost suit your own personal taste. Why drink something you don’t like? And why feel ashame liking something that others don’t? For me, I say – bring some brett and VA on! It makes the wine more interesting. More analog. And I respect if you don’t agree.