Continued from Chapter Two, Part Two. Read Chapter Two Part One, and Chapter One Parts One, Two and Three here.

Terroir and the good, the bad and the ugly grapes

In the way that humans like to impute value to systems and impose hierarchies of taste certain arbiters have determined that some grape varieties are inherently more aristocratic than others. Hence, Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Chardonnay & Riesling have enjoyed noble repute, whereas, Carignan, for example, was long judged to be a base grape only capable of making base wine. Associated with vatted plonk du midi, dismissed cursorily by famous wine writers (you know who you are) as “a workhorse variety”; “not capable of greatness”; “should be grubbed up in favour of Syrah”; “the bane of the European wine industry”; and “only distinguished by its disadvantages”, Carignan was truly one of the mal-aimés.

Carignan is a more efficient vehicle for terroir than Syrah and Grenache particularly on the poor schistous soils (worked by maso-schistes) that characterise much of the Roussillon and eastern Languedoc.

In fact, Carignan was (and is) peculiarly suited to the Catalan wine-growing country (and, more generally, to warm Mediterranean climates elsewhere). Hardy low-yielding bush vines with deep root systems penetrating the bare rocky soils yield grapes with the substance to make interesting, terroir-driven wines. A few years ago, some growers grouped together to extol the virtues of wines made from this grape, (www.carignan.com) and, in time, wine writers began to concede that Carignan was much more than an honest dobbin and was capable of producing splendid results in the right hands and with the right methods.

Bad appellations

The appellations, however, have yet to catch up with what’s going on. Although many producers in the Languedoc believe its glory lies with old vines of Carignan, often dating back more than a century, the AOP will not allow for a 100% varietal Carignan. Benjamin Lewin MW writes in Decanter Magazine: “The authorities’ hostility to varietal description extends to appellation rules that wines must be blended, usually from three or more varieties. So, some of the best cuvées of the Languedoc are monovarietals, labelled as IGP or Vin de France, such as Xavier Ledogar’s La Mariole, from 100-year-old Carignan vines.”

Carignan is a more efficient vehicle for terroir than Syrah and Grenache particularly on the poor schistous soils (worked by maso-schistes) that characterise much of the Roussillon and eastern Languedoc. As Andrew Jefford writes in The New France: “The greatest wines of the Languedoc never taste easy or comfortable; they taste as if handfuls of stones had been stuffed in a liquidiser and ground down to a dark pulp with bitter cherries, dark plums, firm damsons and tight sloes.”

Some of our favourite Loire white wines come from vineyards grown on schist. You’d be able to pick them out easily.

René’s thumbprint

Anjou Bonnes Blanches 2007 René Mosse! Bang!!

Yeeahh!

Grrreat Chenin!

You getting the honey notes, membrillo, and right at the end, those typical floral tones?

Yeah. Typical schist terroir!

Yes, you see how rich it is but with such fantastic natural acidity.

It certainly has René’s thumbprint. You’re not going worry about getting that wrong.

Oh, Anjou…when it’s like this…

Oh-oh. I believe I made a teeny-tiny little mistake…

The Mosse is in this carafe. You’ve been tasting the Savagnin from Ganevat.

–Mimi, Fifi & Glouglou, Michel Tolmer

When you talk about granite you think of the northern Rhone (well, I do), although its presence manifests itself as well in wines from the Roussillon, Corsica, the Auvergne, Beaujolais and Alsace. And the Swartland, of course.

#meltedgranite

Time and Thought were my surveyors,

They laid their courses well,

They boiled the sea, and baked the layers

Or granite, marl, and shell.

Does the expression Syrah on granite send shivers of appreciation down your spine? Some things were meant to be – rhubarb and custard, Hall & Oates, port and authority, Syrah and granite.

Wines that knock you on your Cornas

The knowledge that a wine is rare and produced in finger-counting quantities, ratchets up expectation and sharpens one’s faculties. I have been fortunate to try Hirotake Ooka’s (Domaine de la Colline) Cornas twice. On both occasions I rolled every mineral atom of this dark purple liquid around my mouth ensuring that it visited and left its calling card in each nook and cranny of my palate.

Does the expression Syrah on granite send shivers of appreciation down your spine?

His Cornas is a youthful beast to put it mildly. The grapes are grown on decomposed granite soils, harvested by hand, and macerated in tank. After natural fermentation the juice spends 24 months in old barrels before bottling. On opening, this wine tastes like dry granite-scrapings with an afterthought of blackcurrant. Day two, mirabile dictu, it transmogrifies into a sheer beauty, billowing bountifully from the glass, with floral-fruity aromas and lovely smoked blueberry fruit underpinned by crunchy acidity. This is a beautiful natural red, so precociously purple, interfusing sweet floral (violet, cherry-blossom) aromas with hedgerow fruits and herbs. There’s also the characterful Syrah note of marinated purple olives, here a sweet note, there a bitter one and mineral salts in abundance. A young unmediated wine with the wisdom of centuries of terroir. Rarer than rare. When I say is, I mean was – we may never see its like again.

On my second encounter the wine tarried a wee while in a carafe. It was more integrated, fruit and minerals inextricably intertwined, or rather interwined.

It is sad that few people understand naturally made individual wines. Technology has progressed to the point that far too many wines lack the taste of the place of their origin and resemble one another. Terroir, more than anything, is an expression of finesse and complexity.”

–Gérard Chave, as quoted in Robert Parker’s Wines of the Rhône Valley, 1998 edition

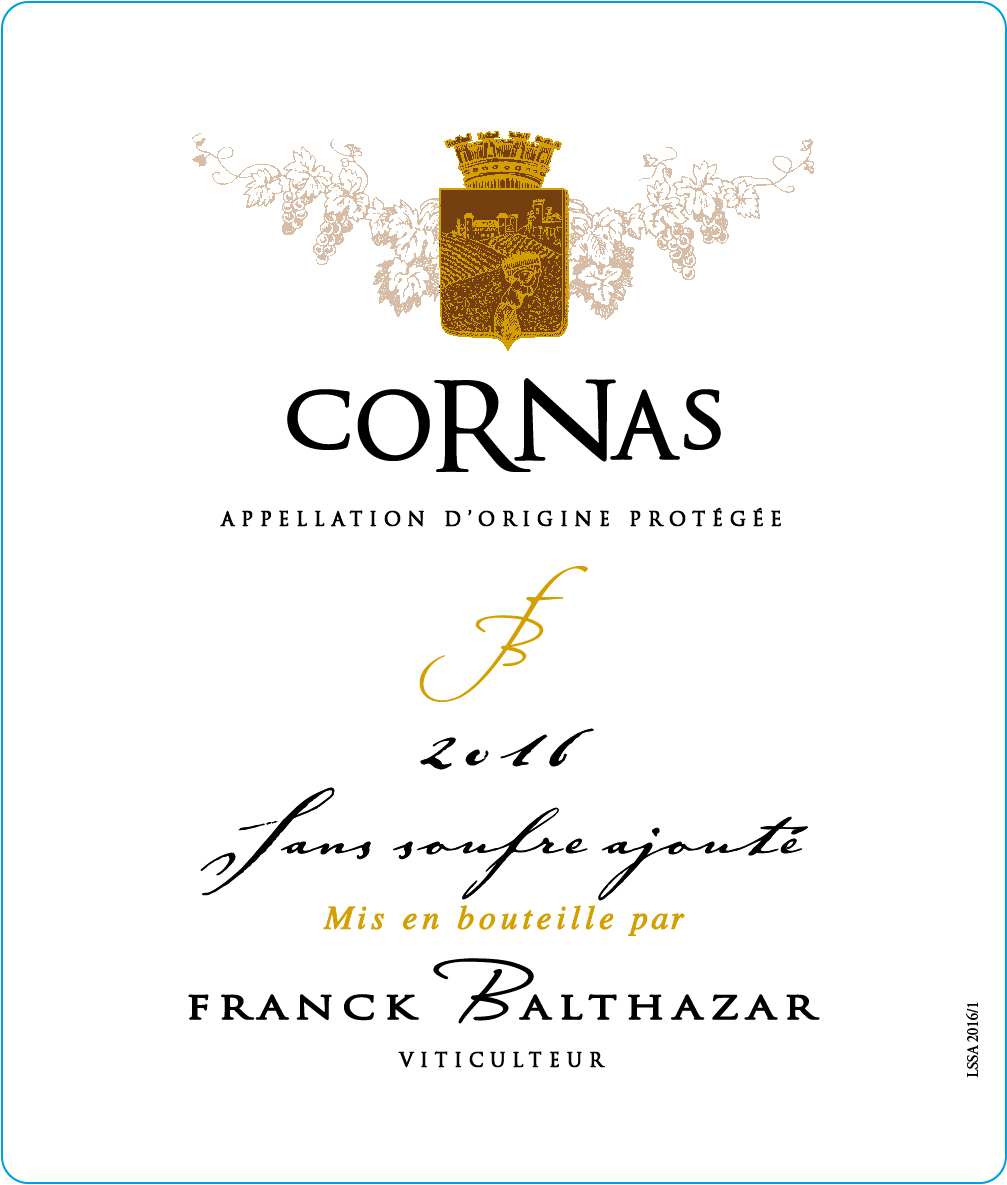

Digression: Decanting Balthazar Cornas

Illustrious Hermitage is spoken with a regal drawl, all languorous and timeless, Côte-Rôtie, with its pleasing assonance and alliteration, trips authoritatively off the tongue, then there is Cornas. Not Corn-ah, mind you but the stubby peasant finalising of “ass.” This tiny rustic island of world-class Syrah floats at the southern end of the northern Rhone. Even the wines seem more rustic without ameliorating Viognier or Marsanne giving that softening floral lift to the liquid. Great terroir meets uncompromising winemaking and the relative success of such vignerons as Clape, Verset, Michel and Juge encouraged others to return to this appellation. One of those was Franck Balthazar, who left his engineering career in 2002 to take up the classic farming and winemaking methods of his father René. A dozen years later, Balthazar is now making some of the most expressive, and rigorously traditional, wines in Cornas.

The Balthazar domaine dates back to 1931, when it was founded by Franck’s grandfather Casimir. Franck names ones of his cuvees after him. René took charge in 1950 and followed his contemporaries Auguste Clape and Noël Verset into domaine bottling on a small scale in the 1970s. All the while he continued to sell most of his wine in cask—as Casimir and so many others of his generation had done—to the local cafés and bistros.

Franck now bottles all of his traditionally-made tiny production. The domaine’s vineyards are planted on the steep slopes of the hillside amphitheatre exclusively to Petite Syrah, the ancient local clone whose small, olive-shaped berries produce a wine of greater aromatic complexity than modern clones.

Farming is organic, of course, and he ploughs between the vines with his horse. In the winery the recipe is simple – whole cluster, native yeast fermentation in concrete vats; manual cap punching; and ageing in old, neutral demi-muids before bottling without fining or filtration. The aging in demi-muid rather than the smaller pièce is fundamental to the domaine’s philosophy. As René Balthazar told Rhône wine expert John Livingstone-Learmonth, “We raise the wine in 600-litre demi-muids because they keep the wine’s perfumes better than the 225-litre casks.”

A key to the superb quality and character of Balthazar’s Cornas are the domaine’s great holdings. These include not only half-century-old vines in Mazards but a 1914 planting of Petite Syrah in the revered Chaillot vineyard, acquired from Noël Verset. Balthazar is also slowly expanding the amount of land under vine; a true son of Cornas, Franck has created terraces and planted vines on previously overgrown land on the steep Légre slope above Sabarotte—demonstrating the Cornasien willingness to develop a backbreaking site for the reward of the aromas and flavours that only Syrah grown here can express.

Franck’s flagship wine is the Chaillot bottling, from the fruit of century-old Petite Syrah vines that create a wine of stunning depth, concentration and complexity. Grapes are harvested by hand from granite-rich soils, about half coming from the ex-Verset parcel and then are fermented whole bunch with stems, with manual punch downs. From here, the wine is moved to 600-litre demi-muids, where they are aged for about 18 months before bottling.

The Chaillot is dark purple and its highly perfumed nose reveals mineral-accented blackberry and blueberry with a background of exotic Asian spice and floral notes. The palate is densely packed but energetic with initial explosive dark berry preserve flavours, before secondary notes of cured ham, Kalamata olive and candied violet and cracked peppercorns kick in. Superb concentration, finishing with bright mineral cut, slow-building tannins and superb persistence. This wine manages to be dense yet aerial, combining heat and coolness in equal measure.

We’ve also managed to secure a tiny bit of the sans soufre Cornas. From younger vines this wine reveals a touch more agility to temper the ink-dark fruit, but it is still so satisfying and complete. The tannins have that medicinal astringency which nourishes rather than dries out the palate. Amongst the bristling blackberry and black currant fruit there is a seasoning of roasted wild thyme that is simply delightful and makes this so moreish.

Younger vines, maybe. The song of terroir remains the same.

#vulcanicity

Love, my territory of kisses and volcanoes and wine.

Enamoured by thorns

I vanish into the vines

Blood turning into honey in the rusty old block

When she burst into blossom

We were on the volcano.

Her voice was silent, like love it came out of mouth

Turning into a petalled coronet.

The end of it was more than

The tremble of a white flower on a vine.

More than the wine-coloured day

It was hot memory of joy

Frozen in the curve of the glass

Melting my mind.

There are wines from vines nestling on, or near volcanoes, and volcanic wine where the soil bears the structure and historical imprint of ancient lava flows. As for the former, Etna is still belching forth the good stuff. Santorini’s volcanic origins are given the full Jefford in the following:

Few wines taste of disaster and catastrophe… [one of the most evocative] was born of a volcanic explosion, many times more powerful than Krakatau, which blew the heart out of one of Greece’s Cycladic islands. The exact moment remains conjectural, but recent radiocarbon dating of a buried olive branch suggests sometime around 1614 BC: the wine is the Assyrtiko-based white of Santorini. It is, for me, the most pronounced vin de terroir in the world. In no other wine can you smell and taste with such clarity the mineral soup and bright sunlight which, gene-guided, structures the grape and its juice. As an unmasked terroiriste, there was no vineyard I was keener to visit…

Santorini has some of the world’s oldest vine roots…in the world’s youngest soils. When you taste a Santorini white, you are tasting a collision in plate tectonics…Like a geological slipped disc, Santorini is where the pain keeps erupting…

Salina, Pantelleria, Tenerife, Iceland (only kidding). Elsewhere, volcanic terroir influence may be detected in some of our Auvergnate reds (Domaine No Control’s Magma Rock does what it says on the tin, as does the Maupertuis Pierres Noires), in certain cuvées from Filippo Filippi in Soave, Andrea Occhipinti’s Alea Viva, Rosso Arcaico from Lazio, and various whites and reds from Campania.

As for Oregon. Many millions of years ago marine sediments were laid down on the floor of the Pacific Ocean and these gave rise to the following soil types: Willakenzie, Bellpine, Chuhulpim, Hazelair, Melbourne and Dupee. After this were the basalts that originated as rivers of lava erupting from volcanoes on the east side of the Cascades flowed down the Columbia Gorge toward the sea, covering the layers of marine sediment on the floor of the emerging Willamette Valley with layers of basalt. The Willamette Valley continued to buckle and tilt under pressure from the ongoing coastal collisions, forming the interior hill chains that are typically tilted layers of volcanic basalt and sedimentary sandstone, such as the Dundee Hills and Eola Hills and resulted in the famous red volcanic clay soils such as Jory, Nekia and Saum.

Kelley Fox farms vineyards in the Dundee Hills and McMinnville. A transient personal feeling about Kelley’s wine. The first sensation (what I smell, when I taste) is the strength of the terroir. There is a Gaelic expression Is Blath an Fhuil – “the blood is strong” – and I feel the sanguine vitality of the respective vineyards pulsing in the wines. Kelley Fox disappears into her wines (for want of a better expression); hers is a reclusive, generative presence – she understands her wines whilst detaching from them. Meanwhile, the taster needs to approach with an open mind and an open spirit; in other words, not burdened by preconceptions of what Oregon Pinot Noir might or should be. When you drink a bottle of Momtazi or Maresh you should embark on a journey – these wines embody everything that is wonderful and intriguing (and occasionally frustrating) about Pinot Noir. They carry the darkness and light equally in their souls, sometimes they are temperamental and sometimes they beam with pure energy. What I love most of all is their opaque transparency. The oxymoron is justified; the wines are limpid, sans veneer, whilst the fruit is dark, volcanic, throbbing. There is deep-rootedness, but not heaviness, textural completeness but not obviousness, flowers, herbs, earth and sky, all rolled into a whole.

Maresh and Momtazi. Authentic and true to themselves. The truth is in the tasting. In lieu of knowing the wines, you can certainly “feel” them.

Once the wines are made, Kelley detaches from them. As the Georgians might say “she put them on their feet.” She might deprecate the notion of being a winemaker. She is a combination of artisan, a translator, a midwife, a sensuous individual. She feels and understands natural beauty; she is brilliant, charismatic (yet reserved), loyal and respectful. The wines reflect that – they make no concessions and are not polished to an easy sheen. They are what they are – isn’t that the essential message of terroir?

Terroir – Earth Rocks

Terroir has never been fixed, in taste or in perception. It has always been an evolving expression of culture. What distinguishes our era is the instantaneousness and universality of change. Before, the sense of a terroir would evolve over generations, hundreds of years, allowing for the slow accretion of knowledge and experience to build into sedimentary layers, like the geological underpinning of a given terroir itself. Today layers are stripped away overnight, and a new layer is added nearly each vintage.

–Jonathan Nossiter, Liquid Memory

Let’s return to our definition of terroir. Scientific definitions abound about the various liaisons between microclimate and soil composition, but they can only scratch the surface of the philosophy. One basic formulation is articulated by Bruno Prats in his article “The Terroir is Important” (Decanter 1983): “When a French wine grower speaks of a terroir, he means something quite different from the chemical composition of the soil…The terroir is the coming together of the climate, the soil and the landscape.” Even this definition seems conservative. In a wider sense terroir embodies the general notion of “respect”: respect for the land and the environment, respect for history, respect for culture. It concerns the wine’s interpretation of place as opposed to the concept of the varietal which tends to be about a nominated or fixed interpretation of a grape in order to obtain an instantly recognisable “international” style. Terroir is a progressive notion feeding on the positive elements of tradition, the age-old intuitive alliance forged between Nature and Man. As Nicolas Joly observes in his book Le Vin du Ciel à la Terre, the creation of the first appellations controllées resulted in “une connaisance intime de terroirs fondeé sur l’observation et l’experience de plusieurs generations de viticulteurs. Une experience qui avait conduit à l’union de tel cépage et de telle parcelle. De ces justes mariages devaient naitre des vins donc l’expression était originale car intimement liée à leur environnement et donc inimitable.”

or

“An intimate knowledge of soils based on the observation and experience of several generations of winemakers. An experience that led to the union of such grape and plot. From these unions were born wines, so their expression was unique because the grapes are intimately related to their environment and therefore inimitable.”

If, scientifically speaking, terroir is the interrelation of soil structure, microclimate, local fauna and flora, we should be able to dissect flavour components in a wine to the nth biochemical degree to see if we can discern whether the wine has physically interpreted its terroir. I believe that this approach goes against the grain (not to mention the grape). I am reminded of something Pierre Boulez once said about great art, but could equally apply to wine: “A landscape painted so well that the artist disappears in it.” When we taste wine, we get an overall impression, an aggregate of sensations. Terroir is the synergy of living elements; you cannot separate its components any more than you can analyse individually all the discrete notes in a symphony and compare it to the whole. In other words, terroir is greater than the sum of its parts. Experienced vignerons can often distinguish the flavour between one plot of vines and another, for the very reason that they have been brought up in the local countryside and know the fauna, the flora, the soil, when the wind is going to change and so forth. The alliance of instinct with knowledge is a kind of romantic inspiration, an intuition borne of living in the countryside which informs the activity of being a vigneron. So, when you taste a wine of terroir your senses will accumulate impressions, as if you were gradually becoming acquainted with a complex, organic thing. Wines lacking this dimension, no matter how technically accomplished, are cold shadows: they are calculations of correctness. Nicolas Joly uses an expression sang de la terre, where sang has two possible meanings: blood and kinship, implying a natural “blood-relationship” between man and terroir and that the earth itself is living breathing dynamic force. I suspect that many French growers would shudder if you called them wine-makers; they prefer to see themselves as vignerons instinctively cultivating the potential of the grapes and faithfully perpetuating their cultural heritage. To return to our musical analogy the vigneron is the conductor who can highlight the grace notes of the wine by creating the right conditions for the vine to flourish; therein lies the art of great wine-making. It is not how much you interfere in the process but how sympathetically.

New Terroirism?

#stonedeaf ~ no terroir character whatsoever

There will always be a vibrant debate between the technicians and holisticians, the boffins and the poets, but the wheel has begun to turn. I am optimistic that the new generation of “wine-makers” (eek!) is beginning to appreciate the value of interpreting terroir and comprehend that our palates may be tiring of synthetic homogeneity. Also, as more quality wine floods onto the market, there is a sense that terroir might be used to more easily differentiate one wine from another, a sophisticated form of branding, if you like. Throughout the world, the most enlightened growers perceive that the future is in the quality of their terroir and that technology should only be allowed to assist, not gloss over inadequacies nor reduce the wine to a lowest common denominator.

Therein lies the art of great wine-making. It is not how much you interfere in the process but how sympathetically.

Opposing wine grape varieties in a metaphorical beauty contest or arm-wrestle is a monumentally pointless activity. Chardonnay versus Gruner Veltliner, Pinot Noir versus Cabernet Sauvignon and so forth. Far better to oppose soil types: limestone versus clay, schist versus granite, gneiss versus orthogneiss, eisen versus blut, dumb versus dumber. Better still to try to understand that terroir has a far richer meaning than simplistic oppositions.

Terroir is the story of the wine, the arc of events in that story, and all the tiny details that make up the big picture. The last word, which is the first word, must go to Pliny who, many centuries ago, said: “The same vine has a different value in different places.”

Stay tuned for Chapter Three…