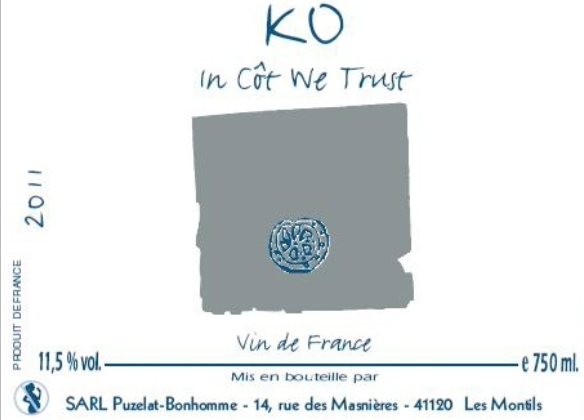

The other day I was trying a wine called In Côt We Trust from the stable of Pierre-Olivier Bonhomme. I remember (back in the time) my first encounter with this Malbec. It was wild, sanguine, hog-roast kind of wine, high on funk, natural wine red in tooth and claw.

I wrote at the time: In Côt We Trust hails from the same whiffy stable of wine as Olivier Cousin’s Grolleau. When you taste it the metaphorical impression you receive is that the wine has escaped its surly bonds and is drunkenly staggering around the place happy to pick a fight with every wine you’ve tasted and every expectation that you hold. Most of the Malbec I’ve come to grips with, even the beefier specimens, have a ramrod up their backside; this version is soft, sweet and smoky with that smell of just-finished fermentation. It seems raw, unfinished, lacking in structure and yet at the same time is very moreish. Its strength is that it tastes so real; that may also be its weakness.

Blood and guts mingle with guts and blood – pitch this Côt at a civet of venison or hare or a game pie or some lamb’s sweetbreads. And stand well back…

This is natural wine at its most ebullient, its blue-purple colour is pricklier than Gore Vidal after a few drinks, exhibits aromas of peonies (I guess), kirsch and caraway and has a gutsy palate flaunting pepper, punchy tannin and stiletto acidity. Climb into this Cot with alacrity…

I’m still partial to the occasional sweaty-bretty, especially when the bacterial element manifests as subtle seasoning rather than the main event, but the reds that now appeal most to my palate have a cool tension. The updated Bonhomme Côt ticked that box with its elegant restraint, stony fruit notes and almost graphite-fine finish. This is not to say that I will forever eschew what Gerard Manley Hopkins described as

…all things counter, original, spare, strange;

Whatever is fickle, freckled (who knows how?)

With swift, slow; sweet, sour; adazzle, dim…

Tastes change for a variety of reason. Some of the earliest supporters of natural wine, have become the most histrionic refuseniks because they perceive them to be unpleasant tasting and faulty. Ironic, because the wines are a lot straighter and cleaner now and more acceptable to a wider range of palates. This might be termed tactical taste, switching horses in mid-stream. Another reason may be that our palates become habituated to a certain style of wine – familiarity breeds contentment – our taste is rooted in the tried and trusted. Opposed to that, the individual who is forever abandoning a previous taste “position”; palatal contrarianism you might call it, as if trying to assault the palate with the shock of the new.

Some of the earliest supporters of natural wine, have become the most histrionic refuseniks because they perceive them to be unpleasant tasting and faulty. Ironic, because the wines are a lot straighter and cleaner now and more acceptable to a wider range of palates

Taste is fluid. It is dependent on the wine and, perhaps more often, the mood. My first encounters with raw natural wines were as a true novice. I had no reference and therefore was entirely open to the novel aromas and flavours that I was experiencing. Often one is in analytical mode, dissecting wine on every aspect of appearance, smell and flavour, and consciously or unconsciously marking it according to normative values. But taste is also what feels good or right at a given moment. And since the way we feel changes constantly our tastes may change accordingly.

*

Interested in finding out more about the wines of Pierre-Olivier Bonhomme? Buy online here or contact us directly…

Retail: shop@lescaves.co.uk / 01483 554750