I have just done my last two wine events for the year which involved a mixture of singing for the suppers of others and riding various hobbyhorses in many directions. I enjoy talking about wine, because it requires a certain amount of story-telling and engaging both intellectually and viscerally with the subject matter in a convivial setting. And if you have a receptive audience, one that is willing to listen and understand, the circuit is closed, and even if the wines do not appeal to the common denominator of taste, some connection may be achieved.

There are many variables that affect the tenor of event ranging from mundane issues such as the shape of the room itself – the quality of acoustics, the layout, whether people are sitting at communal tables or in smaller groups to more qualitative ones such as whether their primary reason for people attending is social (an evening with family or friends) – or whether they are genuinely curious to experience or learn about new wines. It is important to be all things to all people, combining the roles of friendly host and quasi-operatic entertainer. You are not there to sell them wine or proselytise but to make people feel comfortable about wine whilst challenging received wisdom, and all the time demythologising the subject. It is important to have wit, to have an easy relationship with knowledge so that it becomes a kind of mood music. This is a balancing act.

The venue for my final natural wine aria was The Sun Inn, a beautiful pub with rooms in the heart of the impossibly picturesque village of Dedham in what is known as Constable country. The Sun Inn holds a series of wine dinners throughout the year, all of which are avidly attended by local people.

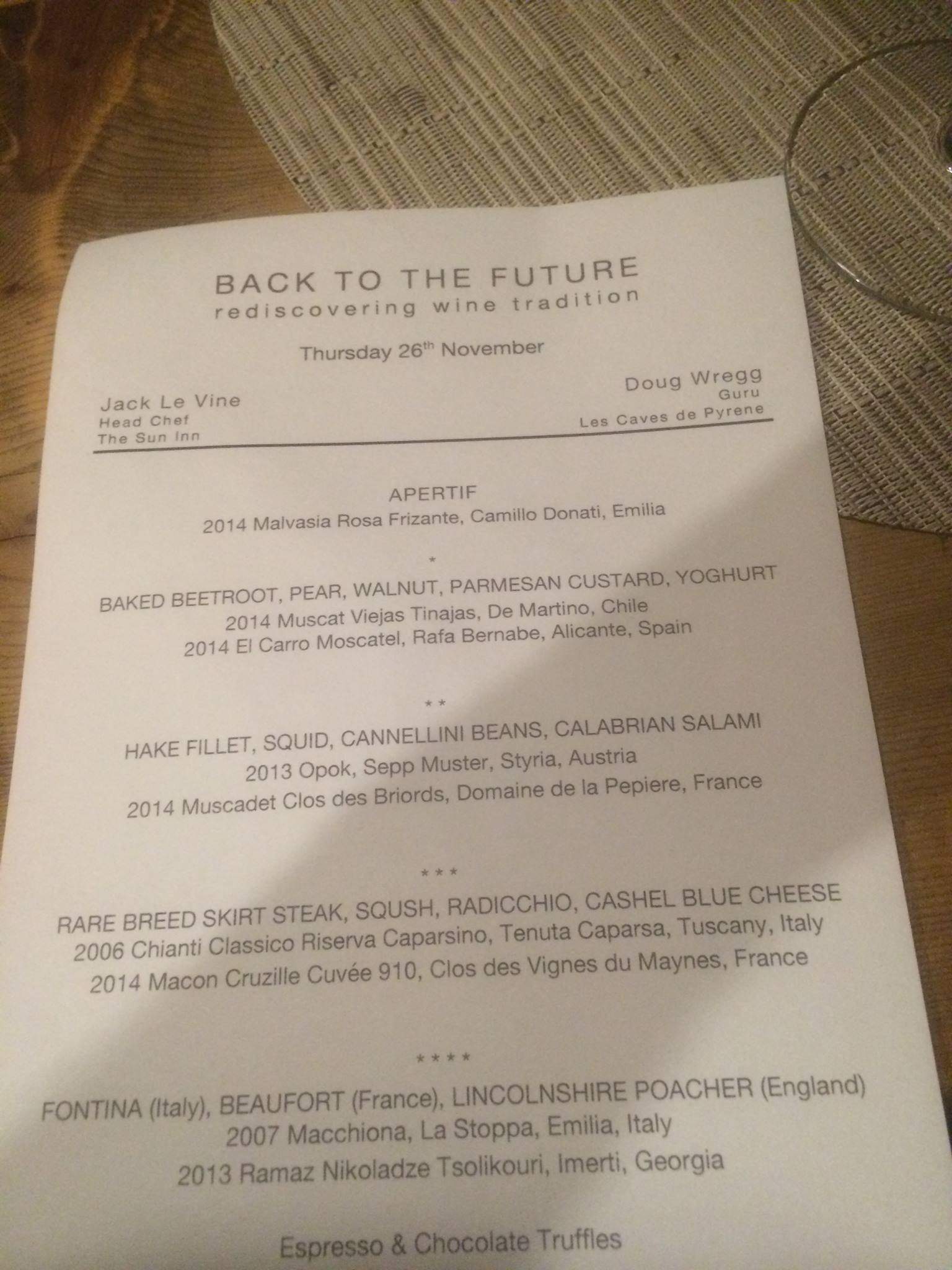

I selected the whimsical theme “Back to the Future with Natural Wines”. It is useful, if a wee bit glib, to have themes as it then behoves you to wind each digression back into one semi-coherent thesis. Often a theme emerges from the thicket of vaguely related ideas. Thus it was we began with an ancestral method sparkler. I could talk about how wines got their bubbles before the champagne roadmap came into place, highlighting the difference between the non-manipulative pet nats – no liqueur de tirage, no filtration, no dosage, no artificial temperature controls, the wine of the vintage and the fruit versus the art of blending and the thickening autolytic process of methode champenoise. Artlessness versus art. We teed off with the Malvasia Rosa Frizzante from Camillo Donati – turbid, gently aromatic, a perfect advert for the drinkability of natural wines. The ancestral method focuses more on the quality of the grapes (Donati only makes sparkling wines) rather the autolytic process and manipulation of grape juice to become a vehicle of bubbles.

Proceeding to the De Martino Tinajas Muscat where I spoke about original grapes (Muscat of Alexandria – as enjoyed by a certain Cleopatra), the history of Chilean viniculture (introduced by the Spanish missionaries who settled Itata and Maule and brought the original vines), traditional farming practices (using horses and old-fashioned hoes), ancient winemaking methods (fermenting and ageing in amphora) and extended maceration (using the grape, the whole grape and nothing but the grape). All this is given extra piquancy by the fact that this family winery had been making avowedly modern wines for the last decade and after deep consideration decided to abandon the commercial safety-first approach in favour of making wines that were sensitive to the region, used indigenous yeasts, did not rely on oak for flavour, were neither alcoholic nor extractive and were fundamentally gastronomic. Looking backward to look ahead, rediscovering a lost wine culture and then adapting it; this is about using traditional knowledge and awareness of local culture and history to renew your wines. It is the empirical approach to making wines more natural.

De Martino’s wine is normally a safe bet, pushing the charming aromatic credentials of the Muscat grape with its notes of jasmine, orange blossom, quince and grape jam yet revealing an extra textural dimension on the palate being herbal and spicy with just a hint of “bite” and some granitic crunch and surprisingly lacy acidity.

Juxtaposed with this was another version of Muscat/Moscatel from Rafa Bernabe’s Vinedos Culturales range – a project where Rafa explores his more natural side. My intention was to show that wine should reflect its place of origin and that the grape varieties are conduits for terroir, accents within the wine rather than the sole driving force.

El Carro, from low yielding bush vines planted on French rootstock on the sand dunes by a Mediterranean lagoon, spends nearly 10 days on skins but seems different in every respect to the De Martino version – more turbid, more phenolic, more bitter (orange oil) and with a strongly smoky reductive accent. In some circumstances people may be more forgiving of a wine that disconcerts them, but here the arrant perversity of the wine, – which was not at its most harmonic – created the feeling (amongst more than a few guests) that natural wines were, perhaps, a con trick, at best, possibly foreshadowing a long evening where they wouldn’t have anything enjoyable to drink!

And all things counter, original, spare, strange;

Whatever is fickle, freckled (who knows how?)

With swift, slow; sweet, sour; adazzle, dim…

Puzzlement – we can work with that. I didn’t want to apologise for the wine nor defend it either. It is important to understand that each wine has its place and its peculiar taste whether we enjoy it or not. This is not so much a question about natural wine in general as one natural wine. There are so many wines that so many people would not drink that not liking something is perfectly okay. However, some might assert that wine should be an understandable product, and if you can’t understand it, then it does not deserve to exist. This is a view propounded by, amongst others, Michel Chapoutier, who was once quoted as saying that natural wines – as he perceived them – should be destroyed rather than sullying the reputation of the appellation. We shall return to this mutton later.

The next brace of wines paired with a fish dish including a Muscadet Vieilles Vignes Clos des Briords from Domaine de la Pepiere. Deriving from a special parcel, “granit de Château-Thébaud,’ made from organic, hand harvested fruit, spending a long time on the lees, the Muscadet exemplifies the move towards single vineyard terroir expression and the notion of cru communale. It seems in this region the more artisan organically-minded growers are leading the way and putting quality above quantity.

Most people think of Muscadet as a bland wine, something generic and anodyne. That orthodoxy which market regions and appellations as brands rather than the respective endeavours of individuals effectively dumbs down wine and lowers expectation across the board. In the future, I suggested, consumers will seek originality, points of difference in our wines, and desire purity of terroir expression, rather than be content safety-first product-for-a-purpose winemaking. That Muscadet can have vaulting ambition and transcend its prosaic image is surely a good thing, but no surprise given that real hand-crafted wines are a consequence organic farming, indigenous yeasts, lengthy lees-ageing to intensify flavour and texture.

Sepp Muster’s Opok white from Styria, the other fish partner, is also a wine born of a particular kind of respectful farming, its roots in a very particular soil type, and nurtured through patient vinification and a slow maturing process. Natural wines such as this have their own sense of deep-rootedness. They have found themselves. What they lack in immediacy they make up by having a solid serious core. We see this also in the wines of Sepp’s fellow vignerons Strohmeier and Tscheppe, who embrace the purist notion that wine should be composed purely of “grapes, love and time”. No falsification, no modifications, just the most intense expression of vineyard and vintage.

The feedback was more positive for these two wines suggesting that people favoured the more primary crispy-crunchy fruit (citrus & salt) rather than the secondary bruised/oxidative style of wine. Our palates have different shapes, and are calibrated to recognise certain aromas, flavours and textures as being more “winey” (for want of a better word). By starting with more challenging wines I threw my audience into the deep end, whereas a more logical approach would be to start with more commercially recognisable styles and ramp up the waywardness over the course of the meal!

Cometh the meat dish, cometh the reds.

It is always wise to have a banker at the wine dinner. I don’t mean someone who wears a pinstripe suit, makes and fritters away fortunes in the City, but a wine that possesses old-fashioned down-to-earth virtues. We call them square wines, or wines which you can see coming. Communicative wines.

Chianti Classico Riserva with some bottle age ticks most of the comfort boxes, although Paolo Cianferoni’s sanguine wines never compromise. Paolo started to make wine with his wife Gianna in 1982. Farming is organic and winemaking methods are intended to express the strength and nobility of the Sangiovese grape. All the Chiantis ferment with their own yeasts for a long time in cement before being transferred to a mixture of old barrels – Slavonian, American, Hungarian and French. The Riservas always need time and are usually released after several years in bottle. 2006 was a stellar vintage; the wine has upfront plum fruit with some deep woody notes at present and some wild herbs and spice in the background.

Opposed to this in every sense was a wine that I feel captures the will o’ the wisp uncertain appeal of natural wines. (I will explain that further). But first a story about Macon Cuvee 910 from Clos des Vignes du Maynes.

The number is a reference to the year when Vignes du Mayne belonged to the monastery at Cluny, which itself was under the management of the Benedictine Order. In that same year the Duke of Aquitaine gave away the monastery to Abbed Bernon, who laid the foundation for the powerful and influential Cluny monastery. The monks living at Vignes du Mayne, harvested grapes and musts, which later were transported, to the monastery, where the wines were raised.

This Macon from this historic vineyard (which was probably the site of a Roman vineyard a thousand years before that) brings us back to rationale of terroir, which was, and still is, finding the best locations to plant vines. We see this especially in Burgundy with the small parcels of vineyard on various slopes denoting geological and climatological distinctiveness.

In 2010, the anniversary vintage – as it were – Julien produced a ‘medieval’ wine, blending grapes from all his parcels together, as would have been done originally, treading by foot and eventually transporting the wine to the abbey on carts pulled by Charolais bulls.

This is a field blend of Pinot Noir, Gamay and Chardonnay, each component yielding subtle tones whilst creating a beautiful ensemble. The Pinot is pure cherry, crunchy redcurrant, the Gamay provides wild berries, a hint of sous-bois and dried fruit. The Chardonnay is the spine of the wine with its acidity and pounded shell minerality giving extra energy and seasoning to the whole.

There are wines that come to you. Then there are wines that you have to listen very carefully to discern what they are saying. They are truthful rather than flattering. Trying to describing the Macon is like translating music into words.

Whereas the Chianti Riserva was widely favoured with the beef, the Macon, to me, had more verve and was a better match. The conventional wisdom is to match powerful flavours with power, but the rustic simplicity of the dish would also allow the beautiful elegance and sheer vitality of the Burgundy to shine as well.

And so to our final odd couple to accompany the cheese course: Macchiona La Stoppa from Elena Pantaleoni and Ramaz Nikoladze’s Tsolikouri, my little Georgian postscript to the dinner.

Elena Pantaleoni’s father, a printer, bought the property in Rivergaro, Emilia in 1973. The vineyards were predominantly planted with international grape varieties such as Cabernet Sauvignon, Pinot Noir, Chardonnay and Sauvignon as was the fashion at the time. The old bottle labels show the Italian names, “Pinò” and “Bordò. At the time, these varieties symbolized “quality” since local varieties were used to make “local” wine.

Elena and her winemaker, Giulio Armani, decided that the climate was too hot to make the best of those varieties. They began replanting those vineyards with indigenous varieties: Barbera, Bonarda, Malvasia di Candia, Ortruga and Trebbiano and in 1996, they began using organic agriculture; La Stoppa was certified in 2008. And, in the cellar, they moved to ever more natural methods. For about ten years, they tried selected yeasts, but they didn’t like the results, then changed to indigenous yeasts, long macerations on the skins, only a tiny amount of sulphites at bottling, no filtration and for many of their wines, a year of aging in wood or steel followed by at least two years of bottle aging. Time is a priceless ingredient of La Stoppa wines. “Some people say they don’t have time,” Elena has said, “but it takes time to make wine well.”

Notably, all La Stoppa wine is labelled IGT even when it qualifies as Colli Piacentini DOC. Why? Because Elena doesn’t believe that the bureaucratic controls of the DOC/DOCG system have any capacity to evaluate the quality of her wine. Instead she points out that the DOC/DOCG/DOP labels, which are supposed to be guarantors of the origin of food and wine, are ironically being accorded to products that have little or no connection with the terroir.

Appellation is debased when it protects special interests and promotes homogeneity at the expense of regional differentiation and quality. The notion of typicity is interesting because in appellation terms it seems to promote wines that conform to a common denominator style, whereas in reality it should refer to wine that expresses “unto itself” its full natural potential. Wine is the life in the liquid not the title on the label.

I also developed Elena’s “slow wine” contention, the idea of “making time for the wine”. As with the Chianti Riserva Caparsino and even the Opok white, Elena’s top wines need time, both in the handling and the necessary maturation, but also in the respect of how we approach them as wines. The 2007 Macchiona is still an infant beast; powerful, gamey wine with notes of bruised black plum, dark cherry and leather and hints of bitter chocolate and port. It is Amarone-like in its intense darkness; a wine for the fireside, and meditative sipping with a sliver of mature hard cheese.

Ending a natural wine tasting with a Georgian wine seems appropriate. When one talks of wine culture, then Georgia and the Caucasus countries are not just where wine originated but it is still informs everyday Georgian existence, a product that is part of the culture at every level. When one talks about the history of a country in terms of its wine, the symbolic power of the qvevri, the endemic hospitality and the fact that Georgia, the birthplace of wine, is now in the vanguard of a wider revolution, introducing techniques of winemaking and wine styles to other countries, then one has a persuasive body of evidence for.

For all that, the Tsolikouri may have played too fast and loose with the majority of expectations. People looked at the golden-amber colour and assumed that it would be a sweet wine, and subsequently felt that the wine was writing visual cheques that the palate was not honouring. And whereas just sniffing it transported me back to the natural beauty of the vineyard and the surrounding smells of sap, wild mint and earth, that “madeleine” moment was peculiar to me. The synesthetic power of wine only works if you have strong memories or associations to flesh out the wine, or, are relaxed, tuned in and therefore sensitive to what lies beneath/beyond the liquid.

Overall, I would say that the assembled folk enjoyed the narrative journey more than the diverse vinous stopping-off points. The wines were perhaps not at their most articulate – normally, they are the bullet points of the thesis. By showing such a variety of styles on the night I had hoped to have a few scattershot hits. However, the wines that might have introduced a wow factor, the slam-dunkers, the epiphany-inducers were not at the feast for our novice audience. Which may be as much to say that natural wines are not meretricious, but demand a degree of extra investment from the drinker.

I topped and tailed my talk by alluding to my first natural wine “epiphany” which occurred in a small wine bar in Paris many years ago when the owner poured me a glass of Olivier Cousin Chardonnay. I had never tasted anything like it before, a wine that was so murky, so wild, so mutable and so alive. It had a natural intensity of flavour and pure energy as if I was tasting it on every part of my tongue at the same time, and although strange, very strange, it was also strangely, shockingly enjoyable. Did I like it? I’m not certain like came into it, but I sure felt it.

The more I taste our “obscure wines” with people (and explain the intention behind them) the more I feel that people are beginning to connect with the wines because they understand why the wines taste the way they do and thus appreciate them for what they are. That is not to say that they are easy wines. You only have to try a Valentini Trebbiano, for example, to understand that real wines are living wines – they taste different on almost every occasion, and, as the man says “Nature does not leap”.

Tastes do change. We are noted as a company for championing the cause of the small grower, for offering variety and for challenging conventional perceptions. The map is being redrawn to reflect quality and interest; more people now want to be stimulated, to experiment and to discover wines which have a story. Trends are illusory and the notion of what will, and what should sell, is based on specious reasoning. Specialist wine companies can help to shift opinion and overcome the restraints of the commercial imperative by sticking to their guns and having faith in growers who make wines with a strong identity. And this is not exclusive to wine; artisan food and drink producers are making a name for themselves, demonstrating that small can be beautiful and successful.

It is said that education is not to reform students or amuse them or to make them technicians. It is to unsettle their minds, widen their horizons, inflame their intellects, teach them to think both within and without the box. Wine dinners could be cosy sermons to the converted or one can use them as opportunities to present an alternative world of wine. So, what price humility? One doesn’t have to recant all one’s previously-held opinions to become a tad more open-minded. As Ben Franklin observed: “For having lived long, I have experienced many instances of being obliged, by better information or fuller consideration, to change opinions, even on important subjects, which I once thought right but found to be otherwise.” In the end a wine dinner is a dinner with wine and a side helping of ideas, and the best way of learning a bit is digesting the ideas through the medium of good wines.