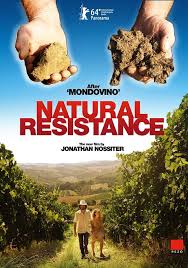

During walks through the vineyards and relaxed gatherings with a group of alternative Italian wine growers, he trades experiences and arguments. What looks like a bucolic paradise, where intelligent people produce wine according to time-honoured and organic methods, is actually revealed to be a battleground. The DOC association, which is supposed to look after the interest of independent vintners, promotes winemakers who produce vast amounts in a standardised quality; and the agricultural industry with its hygiene regulations excludes traditional methods of production. With the help of a film curator friend who contributes treasures from the archives, the documentary compares the restoration of this cinematic heritage with wine culture and reveals surprising connections between intellectual nourishment and bodily sustenance.

–Précis of Natural Resistance by Jonathan Nossiter

Natural Resistance begins in the home of vintner couple Corrado Dottori and Valeria Bochi of La Distesa in Cupramontana (Marche region). They look relaxed and healthy in the beautiful natural healthy environment of the vineyards and talk about their choice to opt back into the bucolic life. The lure of the land and the past.

“I wanted to go back to the wine I had as a kid when I came here… my dad’s old farmhand (would) give me wine that was only grapes and a little sulphur. I drank it and was happy. It was the wine of Cupramontana.”

This sentiment is echoed by Giovanna Tiezzi & Stefano Borsa in Colli Senesi. “Instead of saying “the wine of Giovanna and Stefano”, I prefer saying it’s the wine of Pacina.” That sensitivity to origin, a sense of place and a sense of time, shapes the activity of the vigneron.

One rarely speaks about emotion in wine but wine transports us to many places, including the past. One yearns to drink wines that unlock memories and pleasurable sensations. And the growers want to be reminded of their roots (as intertwined with the roots of the vines themselves). The wine not just comes from a place; it comes from home.

The relationship between the farmer and land is a nurturing one.

“It’s the land that speaks. We’re midwives. Our power lies in respecting completely only what nature gives us. And understanding nature’s time.”

That relationship is based on respectful farming, rebuilding and revitalising after taking from the earth, for what farming was always about was the stewardship of the land as opposed to a predatory exploitation of nature’s resources. Understanding that we need to nourish the soil, protect eco-systems and environment for the health of the vineyards (and other crops) and for our own health. Ecosystem is not merely a buzz word – it connotes promoting and preserving a living, breathing, regenerative earth that works in rhythms and cycles

Natural wine harmonises with these rhythms – it is not solely about creating a product, tracking the taste of the mythical consumer or satisfying some misconceived appellation rules. It is a way of life.

And this brings us to terroir.

Terroir-vision – more than location, location, location

Matt Kramer once very poetically defined terroir as “somewhere-ness,” and this I think is the nub of the issue. I believe that “somewhereness” is absolutely linked to beauty and that beauty reposes in the particulars; we love and admire individuals in a way that we can never love classes of people or things. “Beauty must relate to some sort of internal harmony; the harmony of a great terroir derives, I believe, from the exchange of information between the vine-plant and its milieu over generations. The plant and the soil have learned to speak each other’s language, and that is why a particularly great terroir wine seems to speak with so much elegance.”

Randall Grahm continues this theme: “A great terroir is the one that will elevate a particular site above that of its neighbours. It will ripen its grapes more completely more years out of ten than its neighbours; its wines will tend to be more balanced more of the time than its unfortunate contiguous terroir. But most of all, it will have a calling card, a quality of expressiveness, of distinctiveness that will provoke a sense of recognition in the consumer, whether or not the consumer has ever tasted the wine before.”

Expressiveness, distinctiveness: words that should be more compelling to wine lovers than opulent, rich or powerful. Randall is talking about wines that are unique, wherein you can taste a different order of qualities, precisely because they encapsulate the multifarious differences of their locations. Like so many French growers he posits that the subtle secrets of the soil are best unlocked through biodynamic viticulture: “Biodynamics is perhaps the most straightforward path to the enhanced expression of terroir in one’s vineyard. Its express purpose is to wake up the vines to the energetic forces of the universe, but its true purpose is to wake up the biodynamicist himself or herself.”

Olivier Pithon articulates a similar holistic credo. “I discovered… the sensitivity to how wines can become pleasure, balance and lightness. The love of a job well done, the precision in the choice of interventions, the importance of tasting during the production of wines and the respect for the prime material, are vital. It may sound silly, but it’s everything you didn’t learn at school that counts. We never learn that it’s essential to make wines which you love. They never speak to you about poetry, love and pleasure. It seems natural to me to have a cow, a mare and a dog for my personal equilibrium and just as naturally comes the profound desire and necessity to fly with my own wings or to look after my own vines. Ever since then, I’ve had only one desire: to give everything to my vines so that then they give it back in their grapes and in my wine. You must be proud and put your guts, your sweat, your love, your desires, your joy and your dreams into your wine. Growing biologically was for me self-evident, a mark of respect, a qualitative requirement and a choice of life style. It’s economically irrational for a young enterprise like mine but I don’t know any other way to be than wholly generous and natural.

I don’t do anything extraordinary. I work. I put on the compost. I use sulphur against the vine mildew and an infusion of horse tail for the little mildew that we have. This remains a base. As time goes by, through reading, exchanging ideas, wine tasting and other experiences, the wish to take inspiration from the biodynamic comes naturally. Silica and horn dung (501 and 500) complete the infusions of horse tail, fern and nettles which I use. My goal is to make the wine as good as possible by getting as much out of the soil as I can, whilst respecting our environment and considering the problem of leaving to generations to come healthy soil: “We don’t inherit the land of our ancestors; we lend it to our children”.”

Terroir – because one word is so freighted with meaning, because the critics perceive it as a “concept” appropriated by the French (the word is French after all, and a reflexive mot-juste!) and given a quasi-mystical, pantheistic spin, people will argue in ever-decreasing circles whether it is fact – or fiction. Who deniges of it? As Mrs Gamp might enquire. If you are a New World winemaker the word may have negative connotations insofar as it may be used as an alibi (by the French mainly) covering for lack of fruit or bad winemaking technique. The same people believe that terroir is solely associated with nostalgia for old-fashioned wines and a chronic resistance to new ideas. This is a caricature of the idea (terroir is not an idea), as if the term was invented to endorse the singular superiority of European growers. It is not old-fashioned to pursue distinctiveness by espousing minimal intervention in the vineyard and the winery, rather it denotes intelligence that if you’ve been given beautiful, healthy grapes that you translate their potential into something fine and natural. It is not old-fashioned to talk about spirit, soul, essence, harmony and individuality in wine even though these qualities cannot be measured with callipers. The biodynamic movement in viticulture and the Slow Food philosophy are progressive in their outlook and approach. Underpinning all their ideas are the notions of sustainability, ethical farming and achieving purity of flavour through fewer interventions. And so we return to the matter of taste. We say, as an intellectual truth, that every country or region naturally has its own terroir; however, not every vigneron has an intuitive understanding of it and, as a result of too many interventions – the better to create a wine that conforms to international models – the wine itself becomes denatured, emasculated and obvious. Eben Sadie, a South African vigneron, articulates his concern about interventionist winemaking: ‘I don’t like the term “winemaker” at all’, he explains. ‘Until recently it didn’t exist: now we live in a world where we “make” wines’. Eben continues, ‘to be involved with a great wine is to remove yourself from the process. In all the “making” the virtue of terroir is lost’.

Kelley Fox, a vigneron in Oregon, espouses a similar credo:

My wines are the two vineyards (the grammar is intentional-they are those vineyards), Maresh and Momtazi. Both volcanic soils. I love working with the young volcano energy here. My approach comes from a conscious intention of emptiness- a state of no-self. I wrote somewhere, that I am not Pygmalion. I have exactly zero goals for the wines other than strong transmission of the place and the year, etc. The wines are themselves and are free. I can write about them like this, because these things have nothing to do with me.

Terroir is about such respect for nature; you can obviously force the wine to obey a taste profile by artificial means and it will taste artificial. The great growers want to be able to identify Matt Kramer’s “somewhereness” in their wines, the specific somewhereness of the living vineyard. Yes, these wines have somewhat of the something from a particular somewhere, or to put it more reductively, they taste differently real.

Protecting Diversity

Respect the grape vine and respect the terroir and butterflies may emerge from lumpen caterpillars. Camillo Donati, a biodynamic natural vigneron who farms vineyards south of Parma, describes his approach to unfashionable Trebbiano, one of the most widely planted white varieties in Italy “… at that time winemakers used to plant Trebbiano for its distinctive generous productivity. Today, it has almost disappeared from our area, unfairly snubbed as a light wine of little importance. In 2004 I had my first experience in making wine from this kind of grape and, once easily overcome perplexities about its poor reputation, I noticed, as usual, how Nature, and Vine, in this particular case, is very generous if we only manage to accompany it with humility, deep respect and a lot of love along its seasonal cycles. The result is an astonishing wine, to say the least, likeable, graceful, and, at the same time, with its definite and determined scents and tastes.”

And then is the Trebbiano d’Abruzzo from Edoardo Valentini, a man once known locally as the “Lord of the Vines.” This resolute old-timer disregarded all modern conventions and wrapped his operations in a shroud of mystery, fervently guarding his production techniques from outsiders. His Trebbiano took on uncommon colours, aromas, depth, complexity, and ability to age. Valentini’s wines display a startlingly natural character, their individual quirks only enhancing their profound charm.

Edoardo Valentini’s Trebbiano d’Abruzzo seems to hail from another planet; no-one has a clue why the wine is the way it is – we’ve found that its optimum drinking period is 10-15 years from vintage. Francesco, Edoardo’s son, expounded his theory to us. In the 1950s with the industrialisation of the Italian wine industry the Trebbiano Toscana was imported into Abruzzo to supplement the local version. Being a more robust, high-yielding variety with bigger grapes it eventually entirely replaced the indigenous Trebbiano of Abruzzo (and thus became known itself as Trebbiano d’Abruzzo). The Valentini family, using records dating back to the 1860s, discovered the properties of the original Trebbiano and using massale selection (over a period of 40 years!) in one vineyard of 2.5 hectares have essentially recreated the old Trebbiano with all its unique qualities.

Indigenous grapes, the channelling of terroir, espousing singularity and identity, the rediscovery of traditional techniques (of farming, of winemaking), all give colourful diversity to the often monochrome world of wine where commercial relevance and reputation are continually bruited. The grape variety itself is one small element in a larger picture. Respected, and linked to its place of origin, its purpose is more than a functional “varietal”, it is that which provides cultural variety, embodying the very specific DNA of the locale and the growing season.

Diversity and the individual

Stefano Bellotti explains how vineyard selection is designed to control outcomes.

Vines have always been reproduced by plant selection called “Massale”. They took from each different plant in a vineyard. So they reproduced not an individual, but a diverse population. In the last decades though, they reproduced “clonally”. Because these vines are very old they’re a massale selection. There’s not a single plant that – it’s all Dolcetto, but not a single bunch is like another.

Every plant has its own shape.

They chose the fattest and most productive clone. And they cloned only that. Look at the difference between these bunches. This from that. You see it’s the same type from the leaf and colour of the shoot. From the leaves and the colour of the shoot, they’re the same. It’s all Dolcetto. That one there’s also different. The grapes themselves are fatter. This bunch is smaller, less productive.

But the grape is fatter. So this grape will be juicier than the others. The resulting wine, if they were all like this, would be they’d have less colour and tannin. Instead, a little of this one, that one, the other… it creates harmony. It’s a kind of population selection. Like when the Germans decided to remove the Jews, Gypsies, homosexuals and Communists… it was a “clonal” selection.

…To be continued in Part 2…

Pingback: Natural Resistance: The struggle for the soil and soul of wine. Part 3