In the first two parts of this piece about grape varieties and original styles we examined how local regional grapes were beginning to make a comeback. Here we consider the reputation of various commonplace grape varieties and ask whether the modern penchant for style is at the expense of substance (and soul).

Fashion and make-up

Quality is invariably in the eye of the beholder. In the original grape compendium, Vines, Wines and Grape Varieties, Chenin is not considered worthy of a place at the high table of noble grape varieties – yet Semillon is. Which begs several questions. Firstly, if one great wine (according to the critic) is made from a particular grape variety, does that mean that the grape variety is inherently capable of greatness? Or are freak incidences of great winemaking (or exceptional terroir) – exceptions that prove the rule? Moreover, is not the overall picture complicated by the fact that greatness in wine is always determined by the end product rather than any intrinsic properties of the grape variety? Which might lead one to speculate how much of Chardonnay’s nobility is due to its upbringing on active limestone soils, or, if you stripped away the new oak garnish from Tempranillo, whether it would be perceived as such a premium grape. And do not old vines always play a part in the quality of the wines? And where do clones and rootstocks fit in? And viticultural methods? When you add the art of nature to the science of winemaking, the actual grape seems to be just one small variable in the overall equation. Yet though the final wine may be the integration of myriad complex components, the grape variety is often the sole marketing peg on which the reputation of wines is hung.

What’s in your grape?

Take Sauvignon (take it, I say), a supremely popular grape that stands out from the crowd due to its, ahem, distinctive aromatic methoxypyrazines. How does Sauvignon come to have this particular formulaic identity? Formula winemaking – take high yielding, early machine-harvested grapes, a cold stabilised must which is then fermented with cultured yeasts, heavily sulphured, filtered and fined. The result is all about the externals rather than the substance, like the flower without its stem.

The countervailing approach is to treat the Sauvignon as a grape capable of delivering great flavour. This may be achieved by working selectively and proactively in the vineyard to secure grapes that are richer in matter and to use a lighter touch in the winery. Farming organically or biodynamically, reducing yields, harvesting later and by hand, fermenting (by terroir) at ambient temperatures with indigenous yeasts, perhaps allowing the malolactic fermentation, not filtering and only adding a modicum of sulphur dioxide, will yield a wine that is the polar opposite of the confected Sauvignon described above.

Ironically, many in the trade would claim that the natural versions are unrecognisable as Sauvignon, whereas it should be argued that this is what Sauvignon really tastes like rather than the chemical facsimiles of a wine, wherein the grape variety and terroir nuance have been thoroughly suppressed.

Fade to Grigio

If the differences outlined above between Sauvignons are as chalk is to cheese then nowhere is this more manifest that in the Pinot Gris/Pinot Grigio dichotomy. This prolific grape trades on image, but what that image is, is anybody’s guess. The version in Alsace is golden, rich, waxy and spicy, a wine for food; on the flipside, milquetoast wines from the same grape variety are produced in Veneto, Lombardy and in the south of Italy. Tesco, for example, list 40 + examples of Pinot Grigio on their web-site. It is as though the grape variety is being marketed through its transcendent neutrality. It is the cold-filtered lager of the wine world.

Go to Friuli, however, and you will still find the traditional ramato wines, wherein Pinot Grigio, having been fermented with the grape skins, acquires a coppery tinge, delicate floral notes and an almost granular texture. That the neutral stuff is marketable because it has moved so far away from the original style of the grape variety (some might contend the wines have moved away from wine altogether) says much about the limited commercial outlook of the wine world.

Trace of origin and typicity naturally vanish with elaborated winemaking. For when, say, a white wine is made in such a clinical way with cultured yeasts, cool-fermented and strip-filtered to name but three of the denaturing processes then the grape variety does not matter a jot. Thus a Colombard from Gascony tastes identical to a Fiano from Campania or a Verdehlo from Australia.

The culture of flavour

Before wine was transported across the globe, before oenologists arrived as plenipotentiaries of good taste to declare what was correct or commercial, dictate how the vineyards should be managed and what techniques were necessary to polish the wine to an agreeable shine, wine was usually made for the table (or local tables) with grapes that were locally grown. These grapes would simply be harvested as and when, co-fermented, the under-with-the-over-ripe. There was no critic to please, no standards board to satisfy, no world market to track.

These were undoubtedly simpler times! Fast forward to contemporary arguments about the nature of typicity. Oenologists will argue that typicity and terroir may only be truly captured by clean winemaking. Natural vignerons, conversely, believe that such cleanliness is sterile, denaturing the liquid, uncoupling the wine from everything that gave the grapes their original distinctiveness and edge. These latter growers are often frustrated by appellation authorities and tasting panels that connive in the counsel of imperfect perfection. Defending local grape varieties, using historical artisan practices, attempting to capture the soul of the land and the spirit of the vintage seem to be less important to some than upholding a pseudo-scientific notion of varietal correctness (which is varietally fake).

The move towards natural wines, especially the use of very low or no sulphur, is a force directing vignerons away from appellations. As Benjamin Lewis wrote in a recent article for Decanter:

“When the authorities criticised Patrice Lescarret for ‘oxidative notes’ in his Gaillac wines, he replied: ‘Who are you to suppose that you hold the key to the sacrosanct typicity? Who authorised you to prevent the consumer from experiencing the real taste of wine? Who taught you to taste?” Received authoritative wisdom creates stifling bureaucratic norms and embodies Pope’s aphorism that “a little learning is a dangerous thing”.

The powers that be base their approach on standardisation (rather than standards). Preconceptions rule rather than knowledge, imagination, wisdom or wit. The South African wine standards board is particularly deficient in these qualities, challenging any wine that does not conform to its incredibly straitjacketed interpretation of correctness.

Regional identity

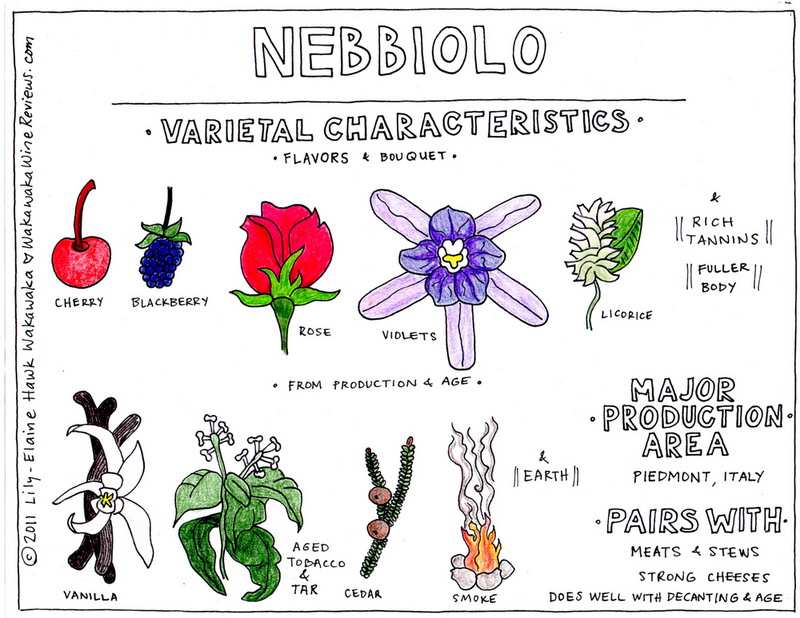

Certain regions proudly claim certain grape varieties as their own: Nebbiolo is naturally associated with Piedmont, Pinot Noir with Burgundy, Gruner Veltliner with Wachau and so forth, and it is generally considered that the most authentic flavours of those grapes may be discovered by drinking examples of wines made in those respective regions.

That the physical and cultural roots of grape varieties are intertwined is an attractive notion, but it is pretty clear that we are not drinking the same wines that previous generations enjoyed. There are myriad reasons for this. The way the vines are trained is different, farming equipment and techniques have changed, different clonal material is being used, winemaking technology has introduced a host of novel interventions and correctives, the size, shape and substance of the vessels that the grape juice is fermented have been rejigged. And tastes have changed; indeed the very rationale of drinking and assessing wine has completely altered over time. What may have been deemed a drinkable wine a hundred years ago might now be summarily dismissed as unpalatable; meanwhile the desire to classify and stratify has created a new hierarchies of taste. The wine is now measured against highly specific critical and commercial norms and is expected to conform to them.

Wine styles do change from generation to generation. Nor is this simply an old-world phenomenon. If you are fortunate enough to taste vintages from Australia, Chile and South Africa from the 50s and 60s you will be amazed by how light, fresh (and still tasty) the wines are. But the most obvious example is the once pale clarete of Bordeaux, now transformed into the lush plush, deeply-coloured oak bomb– the combination of long hang-time in the vineyard, micro-oxygenation and new wood – amongst other vinicultural “developments”. Classic burgundy-hued Pinot Noir all but disappeared for a decade or two when multiple winemakers latched onto Guy Accad cold-soak method.

Nebbiolo, romantically associated with tea, tar, roses, spice, aniseed and dried fruits has its singular angularities hammered out by being aged in new French oak barrels. In the end as a winemaker said, the wine should taste of place and not the forest from which the oak was hewn. Autres temps, autres moeurs. Rather than leave the grape juice to find its own feet in its own time, winemakers are “hot-housing” it for rapid and instantly gratifying results.

Extraction = Subtraction

A few years ago I attended a Wines of Chile tasting in central London. Two noble grape varieties, Pinot Noir and Syrah, were being showcased, with a separate table devoted to each. I tasted the table of Syrah and thought them the most impenetrably dark, chocolate-textured wines I had ever encountered. Except then I arrived at the Syrah table and realised that I must have been tasting Pinot Noir all along!

If this sounds like an indictment of the commercial desire to polish and bulk up, then it is. The grape variety as the means to the end of making wine in a-style-to-impress – not to drink for pleasure, not to marry with food, but to wow with its gaudy yet monolithic architectural awesomeness, resulting in wine that is both vast and trunkless (to coin a phrase).

The other week I noted the results of a comprehensive tasting of the wines of Cahors. Most of the top end examples sported bludgeoning abvs of 14 – 14.5%. There was a 15% and even a 16%. The traditional pink-hued, high acid, herbaceous style of Malbec has evidently been largely cast aside in favour of producing a densely-caparisoned faux-Argentinean style.

Commercial, critical and bureaucratic forces serve to mould the styles of wines in the market. Individuals who march to their own beat and are intensely curious about autochtonous grapes, terroir and authenticity provide the countercultural balance. As well as grape growers they become de facto cultural archivists, rediscovering then conserving traditional practices. Indigenous grapes are denominators of local identity in an ever-changing world; vinified sympathetically they are small beacons of originality in the world of homogeneous wine.

Power corrupts. Winemakers now have the power to manipulate the grapes, must, & wine thoroughly. And so, they do. The reasons and temptations are many.

To my palate, the greatness of many wines reputed to be great is real. However, I believe great wines can come from unexpected places and varieties (and from varieties unexpected in certain places). So while grand reputations are often merited, they are also largely accidental. Gaillac once had a very grand reputation. When a great wine is produced there no, almost nobody notices. Just an example. -michael

Thanks for your comments, Michael!

A great series of posts.

I am quite enthusiastic about the return to native varietals both in wine grapes, and across the board in agricultural disciplines. Of note, in the US there is a push to reestablish, or highlight lost varietals of apples that I can guarantee 90+ % of the public here wouldn’t even know existed. Orchards in New York State often have manifold selection in great contrast to the monotony of available green or MacIntosh awash in herbicides and pesticides.

I like to think that many are finally tiring, or tired, of a select few, or an industry, deciding what is, and is not good. It will be interesting to see if it stays, or is merely a passing fancy.

I recently read in a book on Italian native varietals that Valle d’Aosta has been an area particularly involved with highlighting and saving its regional grapes. I’m nowhere as studied on wine as you, or many of your readers, so I can’t say from experience. I find it exciting, however, if it is the case. (It has also peaked my curiosity for the Ner d’Ala grape.

100% agreement with you here: Indigenous grapes, the channelling of terroir, espousing singularity and identity, the rediscovery of traditional techniques (of farming, of winemaking), all give colourful diversity to the often monochrome world of wine where commercial relevance and reputation are continually bruited.