Grizzled vets don’t have to grizzle to be accorded that status. But they have to have seen a reasonable amount of wine of all colours and all qualities flow beneath the bridge. I would like to think the more I have progressively drunk the more I understand how I feel about wine, and that my taste has become refined to a particular point. Not refined as in more acute, or better, but in the sense of being more uncompromising and knowing what I want to drink at a given time.

I drifted into wine. As a youth, my knowledge of the subject was slim to none – with slim being out of town. My father had given me homeopathic tasters of Rioja and claret when I was knee high to a grasshopper, but I preferred the flavour of lemon peel soaked in vermouth (don’t ask). Years later at uni, if compelled to drink vino, I gravitated towards the chilliest, most sulphurous Frascati or Orvieto that money could buy for £2,99. Afterwards, under the occasional tutelage of my mother, I ascended in consciousness sufficiently to appreciate the odd glass of Saint-Julien (or was it St Estèphe) and accrue the occasional epiphany as per Alex in A Clockwork Orange: “Oh bliss! Bliss and heaven! Oh, it was gorgeousness and gorgeousity made flesh. It was like a bird of rarest-spun heaven metal or like silvery wine flowing in a spaceship, gravity all nonsense now. As I slooshied, I knew such lovely pictures!” Eventually, getting involved in my family restaurant, I had to take over the reins of a pretty special little wine list and subsequently immersed myself in the subject with gusto.

All wine was beautiful then, because it was novel. And taste was discovering that not all wine tastes the same, that there existed different levels of quality, and thus different levels of response to wines.

My first thought was not “so this is what a natural wine tastes like” – I’m not sure the term existed then, but “wow, that’s different! It’s different and I like it. A lot.”

When I first became truly interested in wine I was instructed to taste in a certain way, to break wine down into its constituent parts and to assess analytically (and dismissively). Cleanliness was next to godliness; true wine would never, and should never, deviate from the “tasting chart norm”. Every professional I knew was educated in the same system and subscribed to its scientific and philosophical certainties. I deferred to my elders and betters, supposing that their experience conferred knowledgeable discernment and because I had always been inculcated to believe that correctness was the final unanswerable proof. Now I realise that complacent conservatism has become systemic. Educators and experienced journalists have told me “I’ve been drinking wine for decades and I don’t expect to have to relearn what is good”. It is naturally upsetting to have one’s preconceptions challenged, but education, if it is to be of value to us, is about constantly questioning and confronting received wisdom. The deference in the wine world to traditional certainties is actually a lazy complicity. Nothing is – or should be – sacrosanct.

Fast forward from my time nuzzling wine text books to a wine epiphany. About 15 years ago, I tasted my first “naturally-made” wine in a Parisian wine bar. My first thought was not “so this is what a natural wine tastes like” – I’m not sure the term existed then, but “wow, that’s different! It’s different and I like it. A lot.” I felt I was being challenged by the wine, that a hundred sensations were taking place in my mouth, that the wine had an energy I had rarely, if ever, encountered. It was alive, as if it had scooped up the soil, the rocks, the plants and churned them into living liquid.

Such experiences serve to realign one’s palate. In some cases, I would imagine that they would deter people from assaying a natural wine ever again! First impressions are certainly important. My curiosity was piqued – how many of these wines existed? Were they all the same? Or equally individual? How come they tasted the way they did and in what ways were they similar and different to the wines I had been drinking all my life? One question leads to many others, and you soon discover that there is a person behind the wine and a story behind that person. You learn about the culture of the region, the geology of the vineyard and the specifics of terroir. You learn about biodynamic practice. And you learn about the winemaking methods. Piecing it all together you begin to understand why the wine is the way it is. One grower leads to another… and another. You taste all the wines – some are wonderful, others are less so, some are straight, others are crazy, some sing of the terroir, others of the process.

The more I taste the more I feel confident in my own likes and dislikes to be able to reject critical certainties. Tasting and drinking wine should be about the wine and one’s responses and not about genuflecting to perceived standards.

Natural wine has enriched my life. Although I have never suspended my critical judgement, however, and don’t simply like a wine because I can call it natural, I do love a wine that tastes natural and pure, raw, edgy, energetic and lively. Sometimes I want fruit, sometimes I seek minerality and structure, sometimes the sensation of spontaneity, and I can find all these attributes in a wide variety of natural wines. Discovering natural wine made me discover a fact so simple that one shouldn’t need to articulate it: that taste is purely (and impurely) a matter of taste, and not something arbitrated by a small commentariat. The more I taste the more I feel confident in my own likes and dislikes to be able to reject critical certainties. Tasting and drinking wine should be about the wine and one’s responses and not about genuflecting to perceived standards.

Over the years wine has become political subject. That’s life, human nature and commerce -and I am part of that world. As well as the job I do every day, I associate wine with relaxation, friendship and laughter. On the whole, it is a lovely world to be involved with. Through wine I have met some truly remarkable people, all of whom have changed my life in one way or another.

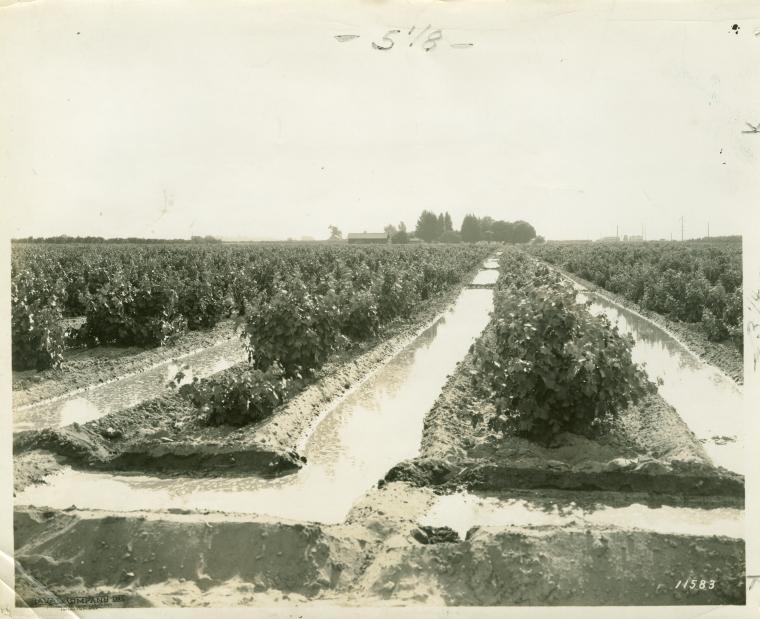

Over the period of my personal journey I’ve witnessed a lot of changes in the wine trade. One is the attitude towards organic wines. Back in the day organic practices in the vineyard were regarded by restaurateurs, wine writers and consumers, as quaint and hippyish, the parole of those who knit their own muesli as well as their cardigans, and, as for biodynamics…well that geomantic Steiner-inspired nonsense was strictly for the cows that jumped over the moon.

The notion of organic farming is now entrenched in our culture and biodynamics is practised by several hundred growers throughout the world – brilliant growers who have seen the health of their vineyards improve markedly. It is fair to say that these ethical and practical farming methods have been embraced by a good proportion of the critical establishment. There are many wine companies specialising in wines from sustainable viticulture. It is not just an ethical stance; wines from organically and biodynamically farmed vineyards tend to be more nourishing, more interesting and more complex as befits the higher quality of farming practice.

Back in the day organic practices in the vineyard were regarded by restaurateurs, wine writers and consumers, as quaint and hippyish, the parole of those who knit their own muesli as well as their cardigans.

Selling methods have also changed over the years. When once it was largely based on hierarchical certainty or brand recognition, there were hard commercial forces at play. Now, there are many more intangibles involved – imagination, recognition and excitement play an increasing role in wine-buying decisions. I have always preferred customers to make their own taste discoveries rather than try to indoctrinate them. If they are really excited by the flavour of a particular wine, then they can communicate that new-minted enthusiasm to their customers. I have learned that genuine enthusiasm (plus letting the wine talk for itself) is infectious, and therefore persuasive. If the wine is farmed with spirit/soul and made with love, it is also more likely to evoke a spontaneous emotional reaction.

Working with wine presents you with a choice. One is to view wine as a product much like any other, to buy and sell consistency, to follow commercial trends because wine needs to be consumer-friendly. The other is to buy what you have faith in selling because you would drink it yourself, and sell with passion tempered by technical knowledge; To feel that wine is not an archetypal product, but something crafted by artisans, made with blood, sweat and tears.

The story of Les Caves de Pyrene is for another occasion. Suffice to say that since I joined the company in 1996 we have gone from a business comprising four people selling a few wines from SW France to a few bistros in London and the South East to one employing over forty people, with other companies in Italy, Spain and Australia, and shipping from hundreds of growers from 18 countries, plus owning four restaurants and organising one of the major natural wine growers’ fairs in the world. Without investment. This growth was organic and progressive, rather than aiming for world domination. Our strength resides not just in sound financial practice and the ability to buy and sell, but in sticking to our guns throughout thick and especially thin, and the way we manage to bring our growers, their wines and our customers closer together. That is what makes the journey worthwhile.