Read Chapter One Parts One, Two and Three

Chapter Two Parts One, Two and Three

Chapter Three Part One and Two

John Wurdeman, Georgian Soul Music

Pheasant’s Tears was born in 2007 when Georgian, Gela Patalishvili, a farmer from a family of Georgian winemakers from Kakheti, and American artist and folklorist John Wurdeman, decided to set up a joint winemaking venture together in order to promote Georgian wines and gastronomic culture. One balmy summer evening a couple of years previously, John had been painting a view from a vineyard near the highway near the village of Tibaani, when he was espied by Gela who was driving back on his tractor from a day in the vines.

Gela called out: “My name is Gela Patalishvili from Bodbis Khevi. Come visit me for dinner.”

John responded: “Why, thank you, but we don’t even know each other. Why am I being invited?”

To which Gela replied, “If you are painting in this place, you must be as crazy about these vines as I am!”

During this dinner and in subsequent discussions Gela explained that various of Georgia’s precious traditions were in danger of being lost and forgotten, from its ancient polyphonic music to its unique wine traditions and qvevri making.

They decided to collaborate, and thus Pheasant’s Tears was founded to celebrate Georgian traditional wine-making, the country’s myriad native grape varieties, and organic farming practice. And, over the years, because of John’s consuming drive, imagination and devotion, it came to represent so much than just the wine itself.

It is fair to say that John fell deeply in love with Georgia and its people. It is a beautiful and rugged small country, with rugged and generous folk, and a rich cultural history, for whom hospitality is an article of faith.

John is a painter, a singer, a poet, a passionate and spiritual man and soul-brother of Les Caves de Pyrène.

John had studied at the Maryland Institute, College of Art in Baltimore before transferring to the Surikov Institute of Art in Moscow where he finished his MFA. He first visited Georgia in 1995 to research its tradition of polyphonic singing, and the following year bought a house in Signaghi, a heritage village famous for the arts, with glorious views towards the snow-capped Caucasus and located in the very heart of the wine region of Kakheti.

The name Pheasant’s Tears was chosen by John and Gela in order to honour the wines of Georgia. According to the OED, the word “pheasant” ultimately comes from Phasis, the ancient name of what is now called the Rioni River in Georgia. It passed from Greek to Latin to French (spelled with an initial “f”) then to English, appearing for the first time in English around the year 1299. The Latin name for pheasant is Phasianus colchicus colchicus– Colchis or Colhidas being an ancient name for Georgia. “In our region where we grow our vines, in Kizikh, there is an old saying that “only the finest of wines can compel a pheasant to cry tears of joy”. Pheasant’s Tears is a short way to pay a big compliment to wine, but only in our tiny part of tiny Georgia!” remarks John.

John is truly indefatigable, constantly travelling both within and outside Georgia, an ambassador for its growers (who are his friends), and the deeper culture of the country. He attends many international natural wine fairs, is closely involved with the event called Zero Compromise in Tbilisi, promotes food and wine through Pheasant’s Tears Restaurant and Wine Bar in Signaghi, The Crazy Pomegranate (which is housed in the winery itself) and Poliphonia in Tbilisi. He has just opened a small boutique hotel with a ranch attached to it. The Travelling Roots company, which he is associated with, organizes visits to wineries, takes in Georgian arts and crafts, and creates travel schedules to feel the beating heart of the country.

John is a painter, a singer, a poet, a passionate and spiritual man and soul-brother of Les Caves de Pyrène.

Digression: Of Tamadas and Gaumarjos! (2013)

While browsing and sluicing wines at Azarpesha wine restaurant in Tbilisi we were introduced us to the role of the tamada. The tamada orchestrates the festivities – he must be a man of humour with a capacity for verbal improvisation and the wisdom of a philosopher with the ability to seamlessly weave a thought into a prayer – and vice versa. John Wurdeman was our host with the most on this first night – the toasts were eloquent and generous and rained down thick and fast. We raise our glasses to the vine that puts its roots into the earth (the temporal/physical) and presents itself to the sun (celestial/spiritual), a synthesis embodied in the very wine itself. We are enjoined to celebrate the different kinds of love, friendship old and new, to participate in a prayer for peace and to recognise the inestimable value of family, tradition and culture.

Poetry is, first of all, a branch of divine wisdom,

Conceived by and known by the godly edifying to all who hear it.

It pleases the ear of the listener if he be a virtuous man.

A poem uttered with surfeit of words lacks grace and excellence.

–The Knight in The Panther’s Skin, Shota Rustaveli

The restaurant has a fantastic collection of traditional drinking vessels and we move seamlessly from draining glasses to toasting each other with wine served in bull horns (called kantsi). These horns would have been cleaned, boiled and polished, creating a unique and durable drinking vessel. For the novice, linking arms and chugging from a vast horn, is a recipe for spilt Rkatsiteli; you tend to end up poking your fellow horny drinker with the sharp end whilst drippily diverting the amber fluid in a southerly direction.

All toasts naturally end with the salutation “gaumarjos” (literally, victory), sometimes followed by “Sakartvelos”. And one toast leads to another and another…and another. And I won’t even mention the chacha. Oh, I just did.

Fire my mind and tongue with skill and power for utterance

Which I need, Oh Lord, for the making of majestic and praiseworthy verses; . . . Generous deeds adorn a monarch as does a cypress Eden;

Even the traitor is won when the hand of the ruler is generous.

Spending on feasting and wine is better than hoarding our substance.

That which we give makes us richer, that which is hoarded is lost.

–Shota Rustaveli

Each person was enjoined to stand up and deliver an encomium. Whereas the Georgian tamada seamlessly slips between the intellectual, emotional and the spiritual, the outsider wrestles to find the right words or simply raises a glass and says cheers. One of our party, Primoz from Croatia, at each banquet – and there were many- stood on a chair and launched into a rendition of “When I Fall in Love” (the Nat King Cole rather than the Doris Day version) in a booming bass voice. That put us all to shame. In subsequent years, I’ve realised that you need to take a copy of Pablo Neruda’s poetry on any trip to Georgia, so you can deliver your emotional-cum-sensual set-piece with maximum lyrical flourish.

But you are more than love,

the fiery kiss,

the heat of fire,

more than the wine of life;

you are

the community of man,

translucency,

chorus of discipline,

abundance of flowers.

I like on the table,

when we’re speaking,

the light of a bottle

of intelligent wine.

Drink it,

and remember in every

drop of gold,

in every topaz glass,

in every purple ladle,

that autumn laboured

to fill the vessel with wine;

and in the ritual of his office,

let the simple man remember

to think of the soil and of his duty,

to propagate the canticle of the wine.

–From Ode to Wine, Pablo Neruda

That always gets them dancing in the aisles.

To coin a cliché, when you spend time with John and his extended family of grower-friends, you are bound to end up with Georgia lodged deeply in your heart. Georgia is endlessly surprising; it clasps you fiercely to its collective bosom. When you meet the people, you feel that they would share their last crust with you and the greatest gift of all, being friendship.

The Creatives

“Alice”

Some write with fearless punkish (and puckish) élan, some with an inquisitive mind and an admirable thoroughness of purpose, some with humour and some with craggy authority, some make you reflect (whether or not you agree with every word) and others make you want to pick up your pen/laptop and write something yourself.

Alice Feiring is my go-to for any nugget of information about natural wine. She feels the pulse of the movement more keenly than anyone and her innate reporter’s instinct leads her to track down and interrogate the story behind the story.

In her own inimitable words:

They’ve called me controversial and feisty but whatever, the fact is that I do find myself leading the international debate on wine made naturally. I found my métier in 2001 when I wrote an award-winning article for the New York Times, “For Better or Worse, Winemakers Go High Tech.” Through researching the topic I uncovered a world of flavor- and aroma-changing additives. “Fraud,” I cried, “Give me my wine back!” And then I went to work.

I have helped to define “natural,” uncovered the abuses of ubiquitous terms like “organic” and provoked readers to share my concerns and passions. Approaching wine from the ground up, I try to work much like an anthropologist to respect and preserve what is indigenous to wines and their traditions. From the ancient vines of the Canary Islands to the qvevris of Georgia, I am attracted to simple, effective century-old practices. I identify wine that unlocks culture and heritage, methods that reflect and relate human stories.

An early attention-getting blogger, in 2008 I wrote The Battle for Wine and Love: Or How I Saved the World From Parkerization. It worked.

I followed that up with Naked Wine in 2011, a narrative romp through the history and the personalities of vin naturel. In short? It’s about the natural wine. You need to read it. Then in 2016 came the immersion into Georgian wine with For the Love of Wine; my odyssey through the world’s most ancient wine culture. In 2017 the subsoils of the vineyard got elevated in The Dirty Wine Guide, written with the help of Ms. Pascaline Lepeltier, Master Sommelier.

Translations of my books have appeared in French, Spanish, Slovakian, Italian and Georgian. In the midst of all of this, in the middle of the 2013 storm, Hurricane Sandy, I launched The Feiring Line, the natural wine newsletter.

I first met Alice at The Real Wine Fair in 2012 where she was curating a small selection of US natural wine growers (she also presented a seminar there), but I had written to her out of the blue after I had stumbled across her on-line blog The Feiring Line. Faring? Firing? Fired up and curiosity-tickled, I sought out a copy of her magnum opus, The Battle for Wine & Love, the reading of which resulted in a lot of furious head-nodding in recognition on my part. Here was someone who told it like it was. Feisty and firing from the lip. Feisty Feiring.

Alice has become associated with the politics of natural wine. Or wine, as we prefer to call it. It shouldn’t be contentious to call on people to stop making dreck and stop drinking dreck, to try to address the subject of chemicals in farming and additives in vinification, to discuss the value of the autochthonous and the artisan, and to understand that many vignerons have undertaken a journey of discovery (and self-discovery), but she initially attracted quite a bit of opprobrium. Whilst Alice has never been afraid to cut through the pretention and vested interests in the wine industry, she is equally an eloquent and impassioned champion of vignerons who put their soul (and their soil!) into their wines.

Alice Feiring is my go-to for any nugget of information about natural wine. She feels the pulse of the movement more keenly than anyone and her innate reporter’s instinct leads her to track down and interrogate the story behind the story.

She has written several books – not all of them igniting a firework under Robert Parker’s derrière! The Dirty Wine Guide is an original take on wine appreciation. We often think of wine in a very square way. For example, we might group wines by their countries, wider region or respective grape varieties. This book takes us back to the vineyards where wines originate and digs both deep into the soil as well as into our very responses and thought processes when we taste. By doing so it raises intriguing questions, rather than dealing in absolute certainties, and shines a new light on the age-old terroir debate. Lucidly written and insightful (with an excellent contribution from fellow-traveller Pascaline Lepeltier formerly of New York’s Rouge Tomate and now Racines). Where soil meets soul – literally.

Alice has written several blog posts on our behalf castigating French wine stupidity. There’s plenty of material to choose from. She’s adept at pricking the pomposity of certain male bastions (Michel Bettane, A Tragedy is the title of one such blog). She is not about venting negative criticism for the sake of it – albeit the wine establishment constantly rises to the bait.

She has also helped to bring Georgia to the wider wine consciousness (she is revered by the growers there), and her support of certain wine regions and vignerons has acted as a clear encouragement to proceed further (both for consumers and the growers themselves). With resonant and original opinions, Alice is certainly one of the most stylish and readable wine writers, recognised in the number of awards and citations that she has received and the huge amount of respect that she has garnered throughout the wine trade and beyond.

Review of For The Love of Wine: My Odyssey Through The World’s Most Ancient Wine Culture

Alice Feiring has been championing the wines of Georgia since she first tried a bottle of the amber stuff in 2011. For her, it goes deeper than reviewing wine qua wine. For The Love of Wine is both journey into, and an evolving love story with Georgia, its people and culture. She brings to life an ancient, yet increasingly vital, country in which food, wine, farming, friendship, Orthodox religion, mysticism, art and poetry, ancient and recent history, are woven into the pattern of everyday life.

Through Alice’s beautifully-written book, we discover a country where wine is written into the very cultural fabric of a society, and suffuses the very souls of the people who live and work in Georgia.

As ever with Alice, hers is no mere objective travelogue. Observations are pointed, opinions matter. But more than simply inveighing against the corrosive effects of globalisation and dull chemical-ridden industrial winemaking, Alice taps into the rich and ever-renewing energy of a people and their cultural story. For The Love of Wine describes series of visits in Georgia, and each chapter showcases a different producer, and often a different region of her discovery. Georgia, we learn is not one country, but many – different grapes in different regions, different styles of winemaking, different family traditions, different styles of cuisine. There are asides, amusing and poignant anecdotes and a sense of emotions being stirred at each encounter. Whilst giving us the lowdown on the country’s colourful history and winemaking she paints vivid character portraits of her favourite growers. With a few judicious strokes – Alice’s economic style is quite brilliant – these people are alive and talking. Each chapter finishes with a recipe.

Growers pour their wines for her, families share their food with her and recount their stories. Alice is family. Hospitality is ritual reality in Georgia. Hospitality is also love. Thus, we are enjoined to realise that these recipes are more than a mere list of ingredients, they are an affirmation of love, of spiritual togetherness, of family. We experience all this through her eyes and are complicit in this love story.

By sharing the culture of Georgia, Feiring seeks to help preserve it. In this way, she mobilizes a kind of cultural jujutsu using the force of globalization — writing a book that will be read internationally, encouraging international distribution of artisanal wines, inspiring international tourism by sharing insights of a unique place — to help make the winemakers’ economy strong enough to support its own local aims and afford its long-standing traditions. Where her writing before has rallied against the homogenizing force of globalization, here she has found a means to use that power for the sake of what she believes in.

—Elaine Chukan Brown, Hawk Wakawaka Wine Reviews

Georgia and her growers are doing a fine job of fulfilling the maxim “Amor vincit omnia”. The love of wine is the life of wine. Through Alice’s beautifully-written book, we discover a country where wine is written into the very cultural fabric of a society, and suffuses the very souls of the people who live and work in Georgia. We understand why growers and travellers go to Georgia and become intoxicated (metaphorically and literally) by what they find. Georgia’s wine traditions have survived religious wars, political upheaval and virtual prohibition. This small country defends its heritage proudly and is a beacon for other cultures to cherish to what really matters – the land, the craftsmanship, the love of wine.

“Sylvie”

The inspiration behind La Dive Bouteille, heralded as the world’s largest annual natural wine exhibition, Sylvie Augereau is one of France’s most prolific wine writers and is a passionate spokesperson for natural wine, to boot. She embodies the good sheer agreeableness of the natural wine world, where having a sense of fun and intellect are easy companions. Sylvie is a reminder to us how much can be achieved with collective good will; one does not have to march to the sound of a political drum to make a big noise.

Here is an excerpt of Christina Pickard’s interview with Sylvie conducted in 2016:

How did you become passionate about natural wine?

Drinking bottles and meeting the people behind the bottles!

Who are the growers whose wines (and personalities) have inspired you?

Of course, Marcel Lapierre, the pope! He made the scorned region of Beaujolais become the first region that one seeks on a wine list, whether to start the meal, to finish it, or even without eating. Anselme Selosse [Jacques Selosse]. He makes the longest wines in the world – with bubbles! And [Anselme] is endlessly thinking and reflecting. Michèle Aubéry [of Domaine Gramenon] embodies the magic of wine. She’s a vigneron who can communicate through the grape; someone who seems to come out from the bottle, like a spirit.

Tell us about La Dive Bouteille. Can you briefly describe the fair? What was the inspiration behind the event? How has it developed?

It is the 17th anniversary of La Dive Bouteille this year! It’s a long story, [how it began], initiated by Catherine Breton the first two years, because she had seen [one of the off-shoot fairs] of Vinexpo. And then I resumed it by reuniting the growers in a barn – they were happy to see each other once a year, particularly when they were misunderstood at home. We could be rebellious, we could be under the radar, we always could sing and dance.

The principle has always been about good wines and good people! And it’s contagious because we bring in thousands of people from around the entire world [to join us]!

Do you think the current system of appellation has any purpose or has it a lost a great deal of credibility with the victimisation of individual growers? Does appellation really defend origin and terroir, and honour tradition?

This role of defending [origin] still exists in some applications thanks to some visionary men and women. Unfortunately, the term is primarily used today to sell large volumes of wine, and small artisans are often denied the appellation because of the facile selection during tastings that exclude wines which stray from the “norm”. But the sad thing is that young winemakers no longer seek this designation, which nevertheless used to defend a sense of origin, and a beautiful notion of the collective.

What is wine journalism in France like? Is the ‘I’ll scratch your back, you scratch mine’ mentality the same there as it is in Britain, where the big brands who wield the most public relations power receive the most attention? Are editors generally up for hearing about ‘unconventional’ wines?

Our great fortune in France is firstly that there is no journalist who is as powerful as Parker. There is a gentle anarchy but very little in the way of a specialist wine press. We only talked about wine at harvest time. But now it is unfortunately only to highlight the supermarket wine fairs! Also, before the big fairs we see rankings of Champagne, because they are the only ones who can really advertise and afford the publicity.

But increasingly the media – as in the specialist as well as the general press – is interested in natural wines, even if it is perhaps with an eye on the Parisian “fashionistas”.

What was it like growing up in the Loire? How has the region changed from when you were a child to now?

It was brilliant! I grew up anchored in the Loire, and then I quickly spent time both down in the cellars and up on the slopes amongst the vines.

The Loire makes humble people. Some also say the people are too modest. Even our Charly Foucault never claimed that he made the greatest Cabernet Francs in the world. Yet it is here in the Loire that biodynamics, [helped in part by] François Bouchet who worked this way in Burgundy, received widespread press. In the Loire we have not been able to defend our grands crus. It often took people from elsewhere to wake them up. Today the Loire is one of the most dynamic regions, with rich and varied vineyards. Even the Burgundians and the Bordelais visit us in order to understand wine more fully, and perhaps to re-learn the humility that makes great vignerons.

What made you decide to make your own wine?

[After my travels] I then had the opportunity to write. I love it. But I was missing the vines; the outdoors; nature. And above all the nature in a fantastic vineyard site that I had been waiting on for 15 years, with very old vines dominating over the Loire. One day, the opportunity came to me, as the grandfather who owned them was getting very tired. And now I spend most of my time in these vineyards. It was not the desire to make wine but the desire of the vineyards themselves!

“Michel”

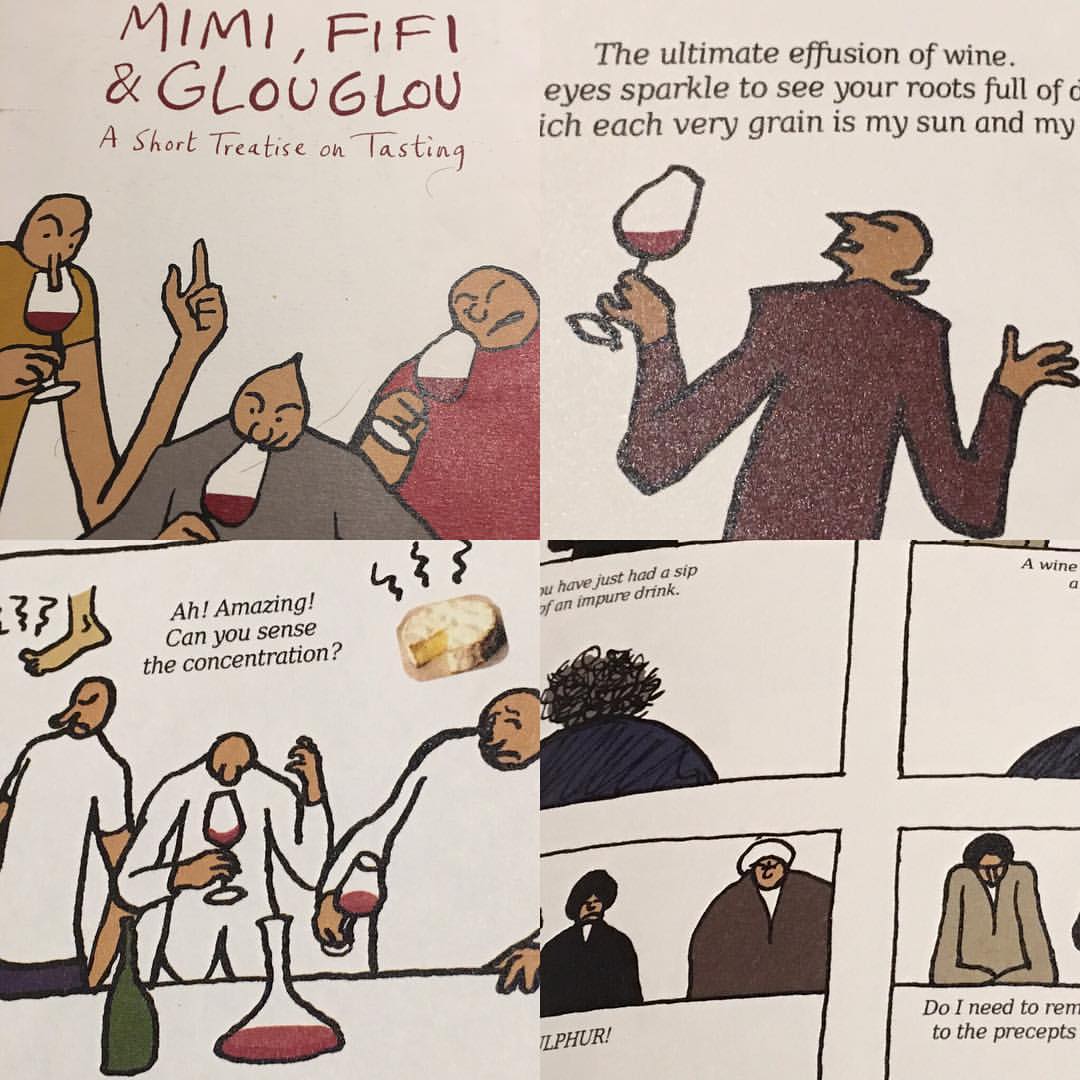

Michel Tolmer is the artist that illustrates Sylvie’s world of natural wine bars, wine fairs and the Parisian “bobos” who think, drink and talk natural wine. He compresses their lovable foibles into his cartoon creations: Mimi, Fifi and Glouglou.

Three differently-sized-and-shaped chaps, brimming with bonhomie, joie de vivre and je ne sais quoi as well as a sociopathic nerdiness that makes them drink wine, think wine, talk wine and dream wine. They are the three musketeers and occasional superheroes of wineupmanship; if a little learning is a dangerous thing then they have a lot of little learning. Tasting is their metier, and blind tasting their delicious boot-camp. For all that they pretend to use the finely-calibrated senses and the pelagic profundity of their knowledge, second-guessing is all part of the armoury, as is sneaking a prior peek at the bottle. Although they are deadly serious at times, they are also les wind-up merchants par excellence – and it is far, far better that someone else fails in their attempts to discover the wine than that you succeed in the same endeavour. Occasionally pretentious themselves, they loathe pretention in others, and no matter how busy they are, and how literally drowning in an ocean of work, there is always time for a three-hour lunch with another bottle of Chiroubles before the attack of poire Cazottes.

Michel is the author, illustrator and puppeteer of our three heroes, casting them forth on their vinous peregrinations. And although Mimi, Fifi largely revolves around the Paris natural wine scene, that demi-monde of wine bars and tastings, it also touches on wider themes, portraying a largely male world, where hobbies becomes professional obsessions. In this world, knowing/unveiling the identity of the wine is akin to a sexual conquest; conversely and perversely, there is extreme stickling for the rules and rituals of engagement. Just as the wines are pure, so it is with the purity of the quest. For the authentic wine lover in search of the wine grail, the wine must not only be the wine, it must also be the precise vintage.

For all the humour, there is also deep affection. The spirit of copinage prevails. Human vanity being what it is, wine reveals who we are in our cups, but it also serves to bind us together.

It was my good fortune to be asked to translate the first Mimi, Fifi and Glouglou book called A Short Treatise on Tasting (thanks to Eric’s recommendation). I loved the characters; they reminded me of Eric, Philippe and myself when we played blind tasting games, the little epiphanies that we would share, and the silly mistakes we would make. Les Caves de Pyrène and copinage go together… like a carafe and a reductive wine. Not a great analogy, but I’m struggling for one.

“Heidi”

As well as the people who influence or support us, there are those who have become part of our ever-extending family. Heidi Nam Knudsen is one. Her wine buying education began at Whole Foods, then she became manager at Ottolenghi and Nopi, followed by group wine buyer, before moving to Farmacy. Recently, Heidi co-founded A Thousand Decisions, a wine course focusing on natural winemaking and growing methods. Heidi’s acquisition of wine knowledge has always gone hand-in-hand with her passion (and in her case the word is justified) for service and education.

Louis, chevalier de Jaucourt describes hospitality in the Encyclopédie as the virtue of a great soul that cares for the whole universe through the ties of humanity. Judaism praises hospitality to strangers and guests based largely on the examples of Abraham and Lot in the Book of Genesis. In Hebrew, the practice is called hachnasat orchim, or “welcoming guests”. Besides other expectations, hosts are expected to provide nourishment, comfort, and entertainment for their guests, and at the end of the visit, hosts customarily escort their guests out of their home, wishing them a safe journey.

Heidi’s acquisition of wine knowledge has always gone hand-in-hand with her passion for service and education.

The business of hospitality has become more about business than hospitality. Heidi has always viewed hospitality in its original sense.

Over the years she has developed a strong personal relationship with many artisan growers and fearlessly lists wines that she loves. Because she believes in them. Her uncompromising principles have occasionally led into conflict with bottom-line bean-counters and managers who are prepared to cut corners. For Heidi the parole of the restaurateur is not to part customers from the maximum amount of cash, rather to encourage those people to return over and again by making them feel appreciated and stimulated by their dining experience. She is determined to empower people who buy wine and is adamant that knowledge of provenance guides us towards making the right moral decisions.

Demythologising wine has become a cliché, but that is what Heidi is engaged in. If this makes her sound overtly sanctimonious, she is the complete opposite, being humble, friendly, loyal and deeply supportive.

Check out our 2018 interview with Heidi here.

Stay tuned for Chapter Four!