Read Chapter One Parts One, Two and Three

Chapter Two Parts One, Two and Three

Chapter Three Part One

Kelley Fox: Living for the vines

Oregon grower Kelley Fox farms the Old Block in Maresh vineyard which is now celebrating its 48th birthday. It’s Pinot Noir on its own roots with feet plunging deeply into red jory (volcanic) soils. The whole vineyard has a strong personality; it shoots out urgent growth in the form of riotous wild flowers, plants and weeds, whilst tangly brambles stand sentinel at the roots and suckers thrust hither and yon. You can clip, nip and prune to your heart’s content but the vineyard will always come back and poke you rudely. A special place with warm volcanic energy, each vine with its micro-system of life.

One of the greatest lessons I have learned about real wine is that you can’t push it around. Raiding the alms-basket of words and flinging sundry fancy definitions, reducing it to a pat formula, dilutes the mystery and serves to cheapen the process. Great wine, as one grower observed, takes time – that’s the blood, sweats, tears and fears of the vigneron(ne) added to the myriad complexities of vineyard and vintage. Reducing the flavour profile of a single wine to a punnet of blackberries (or whatever) and a stave of oak is a kind of modern fallacy, as it presumes that the winemaker makes the wine for a narrow expository purpose rather than frees the wine to express something truly original about where it comes from.

Sweet is the lore which Nature brings;

Our meddling intellect

Mis-shapes the beauteous forms of things:

We murder to dissect.

Enough of Science and of Art;

Close up those barren leaves;

Come forth, and bring with you a heart

That watches and receives.

Kelley Fox makes real wine. Real is not a word to take lightly even if the wine is light on its feet. She takes quotidians, imperatives and impositions out of the equation. When you taste the wines, you try to respect the underlying processes and understand the place. For these are living wines, aromatically intense yet graceful, wilful and capricious, tough yet tender. They are palpably impalpable.

A brief biography of Kelley: Having been part of a PhD program in Biochemistry at Oregon State University, studying enzymes, she became General Manager and Winemaker of Torii Mor Winery before working a stage at Gibbston Valley Wines with Grant Taylor. Eventually she became associate winemaker at The Eyrie Vineyards, making the wine for the late great David Lett, and moved on to become head winemaker at Scott Paul Winery in 2005. Her wines are bottled under Kelley Fox Wines and she sources biodynamically-grown fruit from the rather wonderful old Maresh Vineyards in the Dundee Hills and Momtazi Vineyard in McMinnville.

One of the greatest lessons I have learned about real wine is that you can’t push it around.

Kelley is the ultimate hands-on vigneronne, farming the vines herself, foot-stomping the grapes, overseeing every aspect of vinification as well as the nuts and bolts of winery management. Her wines have inspired considerable critical acclaim and admiration from the likes of Josh Raynolds, Jay Miller and David Schildknecht and she and her wines have featured in many other books and articles. Here is Schildnecht’s panegyric on Kelley’s Momtazi 2010 to give a flavour:

“In showing me only now her 2010 Momtazi Vineyard, Fox wanted to demonstrate that even 22 months after bottling it’s still a ‘wild animal’ in need of further taming by time in bottle, behaviour she insists is typical every year for her rendition of Momtazi (from clones 114 and 115 planted in 1998). The brash intensity of this Pinot took me by surprise-not to mention by storm-even after she’d tried to prepare me for it. ‘Did you fine this with horseradish?’ was the first thing out of my scoured and invigorated mouth. The energy and incisiveness on display here is matched by an athletic, sinewy sense of leanness and structure. Sour cherry and red currant, holly berry and juniper-all in distilled as well as raw form; beet root and horseradish, inform the sappy fundament of this remarkable, vibrant, grippingly piquant Pinot. Expect a mouth-shaking and enervating performance for the foreseeable future, and quite probably surplus stamina past 2025.”

Kelley’s wines are the living result of a dialogue between earth and air. She enjoys a tactile, spiritual relationship with her vines and is part of that dialogue herself. Her knowledge of them is profound; she feels the wines (almost painfully) as much as makes them.

As far as she is concerned she exists to release and transmit the potential of the vineyard and does it most effectively when she is able to empty herself of emotion and ego. It is, at times, a painful birthing process, but there are compensations such as working in a spiritually healing environment amongst the flowers, the insects and the birds. All this imbues the hot blood of the wine and she is “the heart that watches and receives.”

With this in mind to taste the wines properly is to try to sense them. With so much matter to decipher in the liquid, the tools of language can be clumsy implements. True understanding lies in allowing the wine to reach out to you, unveiling its subtle art/magic by degrees, rather than straining to organise it into pat flavour compartments. The process of understanding is every bit as biodynamic as the culture within the vines, for it involves self-understanding as one of the preconditions for tuning into the natural frequencies of the wines themselves. And this process of open understanding makes the wines nourishing, even healing.

Kelley’s wines are the living result of a dialogue between earth and air.

The wines are beautiful. Not in the sense of being conventionally pretty. Their feet (particularly in Maresh) stand in the volcanic red clay soils after all, but in the more provocative sense of the word. They challenge, they elicit a reaction, they connect you to different places. For me they call to mind the passage in Lines A Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey where the poet Wordsworth is dimly conscious of an animating presence that makes sense of his surroundings.

And I have felt

A presence that disturbs me with the joy

Of elevated thoughts; a sense sublime

Of something far more deeply interfused,

Whose dwelling is the light of setting suns,

And the round ocean and the living air,

And the blue sky, and in the mind of man

There is no winemaking formula as such. No commercial yeasts or enzymes or additives. The fruit is harvested in the morning on favourable dates by taste or feel rather than analysis, hand-sorted at the winery. There is no cold-soaking and no pump-overs but Kelley personally does “whole-body” pigeage on the caps. Each block is fermented separately. The Maresh and the Momtazi bottlings so far have been 100% free-run and the wines are pressed at dryness in a modern basket press and both the free-run and press wine are settled-separately-before barrelling down. Malolactic fermentations are spontaneous and bottling is about 11 months post-picking and on biodynamically-favourable dates. Normally the wines are not racked once the barrels are filled at harvest until assemblage/bottling.

The personalities of the vineyards are undeniably and understandably different and Kelley channels them into their final forms. Maresh is on the volcanic brownish-red jory soils of the Dundee Hills – I can attest to their colour since my shoes are now permanently coated by the iron-hued dirt. The vines, planted on original rootstock, are almost venerable – one 2.29-acre block from 1970 is dry-farmed, another single acre block, similarly farmed since 1978. They teem with raw energy and the entire vineyard seems to emit a heady perfume.

Momtazi Vineyard, meanwhile, is in the foothills of McMinnville. McMinnville AVA is a blend of geo-climatic factors that make it unique among Willamette Valley AVAs. Specifically, the area encompasses the land above 200 feet and below 1000 feet in elevation on the east and southeast slopes of the foothills of the Coastal-Range Mountains. Geologically, this region’s soil profile is dramatically different from the other AVAs in the Willamette Valley. The soils are primarily uplifted marine sedimentary loams and silts with alluvial overlays. Beneath is a base of uplifting basalt. Clay and silt loams average 20-40 inches in depth before reaching harder rock and compressed sediments, shot with basalt pebbles and stone. Pinots tend to have a great backbone of acidity and tannin to balance the dark fruits, spice and earth. The Momtazi Vineyards are biodynamically farmed and have a brilliant energy. The place is bright and full of life.

To the wines. From the taster’s perspective I could swallow and regurgitate a lexicon of descriptors (step away from the boysenberries!), but that would be to miss the point. Having said that many have written eloquently and brilliantly about the wines – not least Kelley herself. For me they are strong yet infinitely nuanced –on Maresh I get wild briary fruit interwoven with crunch of souring rhubarb and orange as well as background aromas of mint, wild herbs, earth, fennel, peppercorns and smoke. The herbal tannins lend a medicinal note and the beautiful natural acidity creeps up on you. Momtazi was beaming when I tasted it– there an initial exoticism on the nose (say Turkish delight – is this associative) leading into deeper aromatics of cool, crushed minerals. The wine had a fine depth and cutting edge with saline crunch and beautiful shape and whooshes with sour crunchy black cherry fruit. It is kinetic, salty, sappy and tonic, bursting with life. When I say is, I mean was. The wine does not obey human rules and will always have the last laugh. Both the wines will move in the glass, both the wines will keep something back. With their tautness and coiling energy, they straddle the divide between abrasiveness and elegance.

From the taster’s perspective I could swallow and regurgitate a lexicon of descriptors, but that would be to miss the point.

Words are words for all that and I will always have a special emotional relationship with Maresh. The vineyard is ornery – in clearing suckers and excess vegetation from the base of the gnarly vines I grasped many literal nettles and bumbled into brambles. I inhaled gorgeous natural smells. Each vine cradles its own micro-system – some were a floral and vegetal riot. As Thoreau said:

Nature will bear the closest inspection; she invites us to lay our eye level with the smallest leaf, and take an insect view of its plain. She has no interstices; every part is full of life.

She once wrote: my 2013’s have some of the wilful, moody, unpredictable, taunting, tricky, stormy, and rainbow-y energy of September. Never have I seen so many rainbows during harvest, and the baseline for rainbows in this beautiful land is always high. There appears to be a lot of light inside the darkness in the sky lately and it is exciting in the extreme. And today is the start of my (sweet) sixteenth vintage!”

Each vintage is a year of discovery; the vineyard, whilst true to its personality, sings a different song.

Mirabai, named after the Hindu mystic poet, was the first wine I tried from her. I loved its pinkish-red colour, its leanness and stone-fruit sparseness and al dente quality yet with something lovely and lingering shot through with cherries, citrus and saline flickers.

Kelley’s wines are very real, very individual and yield their secrets in their own sweet time. As a vigneron she responds to the vineyards and honours them in the wine. Every time I drink a bottle of Maresh I am instantly transported there. Terroir is about creating such deep, subliminal connections between people and places.

There’s more. The wines are free. They have their light and their dark, their inner seams and outer delineations. They are strong without being heavy – and above all, they need time, their time.

Wine of wine,

Blood of the world,

Form of forms, and mould of statures,

That I intoxicated,

And by the draught assimilated,

May float at pleasure through all natures;

The bird-language rightly spell,

And that which roses say so well:

Wine that is shed

Like the torrents of the sun

Up the horizon walls,

Or like the Atlantic streams, which run

When the South Sea calls.

Water and bread,

Food which needs no transmuting,

Rainbow-flowering, wisdom-fruiting,

Wine which is already man,

Food which teach and reason can.

Wine which Music is, —

Music and wine are one, —

That I, drinking this,

Shall hear far Chaos talk with me;

Kings unborn shall walk with me;

And the poor grass shall plot and plan

What it will do when it is man.

Quicken’d so, will I unlock

Every crypt of every rock.

I thank the joyful juice

For all I know;

Winds of remembering

Of the ancient being blow,

And seeming-solid walls of use

Open and flow.

Once the wines are made, Kelley detaches from them. As the Georgians might say “she puts them on their feet.” She might deprecate the notion of being a winemaker. She is a combination of artisan, a communicator, a sensuous individual. She feels and understands natural beauty; she is brilliant, charismatic (yet reserved), loyal and respectful. The wines reflect that – they make no concessions and are not polished to an easy sheen. They are what they are and isn’t that the essential message of terroir?

Nothing stays the same, Kelley is working with Pinot Noir from Hyland vineyard; she makes a scything Pinot Blanc from Freedom Hill Vineyard, a sinfully delicious Pinot Gris maceration from Maresh. She is inspired by nature, but also by the wines she loves to drink.

The wines are free. They have their light and their dark, their inner seams and outer delineations. They are strong without being heavy – and above all, they need time, their time.

If you love Kelley’s wines (we’ll call them her wines for the sake of argument), as I do, you’ll learn a valuable lesson in humility. She makes make them for other people to experience what she experiences. You understand that the great wines have a natural arc of development; that the vineyards, the rows and the vines themselves are individuals and that wine is a kind of fluid music where the rhythms are always changing. If you have the wherewithal to tune in you may hear a unique song.

On my trips to Oregon Kelley has also been my Beatrice, a cicerone conducting me hither and yon. I cannot thank her enough for her patience, her understanding and her humour.

The Saffron

The saffron of virtue and contentment

Is dissolved in the water-gun of love and affection.

Pink and red clouds of emotion are flying about,

Limitless colours raining down.

All the covers of the earthen vessel of my body are wide open;

I have thrown away all shame before the world.

Mira’s Lord is the Mountain-Holder, the suave lover.

I sacrifice myself in devotion to His lotus feet.

Mirabai

Craig Hawkins: Beyond the Swartland Revolution

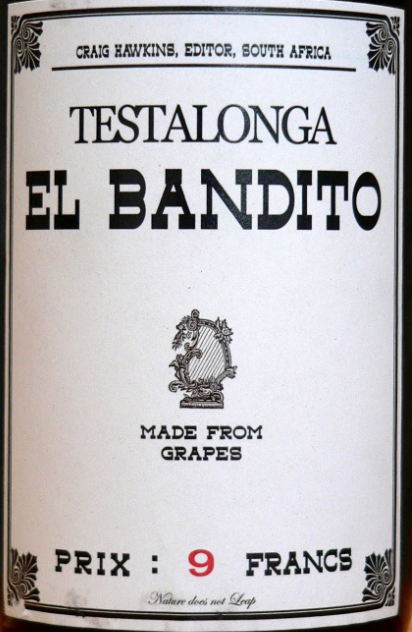

In 2009, I was told about a young grower in South Africa who was pushing the envelope in a notoriously conservative wine culture. He was working at Lammershoek at the time as head winemaker, but had started to make a tiny bit of wine under his own label called Testalonga El Bandito. His first vintage was 2008 and the wine was a skin-contact Chenin.

Eric, Philippe and I met a fresh-faced Craig Hawkins at Terroirs where he showed us his maiden voyage. I adored the bottle with its the wanted poster label and Prix 8 Francs. The wine itself was extraordinary, burnished amber and phenolic, thick with leesy spice, dried fruit and a lemon-sour finish. This was still, relatively speaking, the early days of orange wine.

Craig recalls:

“My very first memory of Les Caves was being introduced back in [2009/10] to all the wonderful natural wines that you had at Terroirs. Sitting in the back-left corner of Terroirs facing the street and you opening so many new bottles that I had never tasted. I met you for lunch at around 11:30 and left closer to 18:00 being already two hours late to a tasting at which I was supposed to be pouring my “day-job wines”. It was awesome…I remember feeling completely uplifted and energised, and knowing for certain then exactly the wines I was going to produce and how I was going to go about it.

“Another great memory also happened at Terroirs, I don’t really get nervous but it was the most nervous I have been in a long time, and that was sitting at the first table on the right as you come in and meeting yourself (Doug), Eric and Phillippe and tasting my first vintages of El Bandito with you. It was a good meeting as it is now the reason I am doing what I am doing today.

“When you guys came out to SA in 2014 and that night at that dodgy club in Cape Town called Deco Dance was a great one, with everyone on the pole, and then sharing a room with Carlo as I had nowhere to sleep. And Eric and Phillipe singing “La Framboise” around the fire. That was a good memory.

“And, finally, my very first Real Wine fair in 2012, It was like being in a dream and having happy hour where all the wines from your natural wine portfolio were around the edge of the room and the banquet tables in the middle, and you could just help yourself and drink and eat. The mackerel was amazing.”

Proust had his madeleines, Craig had his mackerel!

“I remember feeling completely uplifted and energised, and knowing for certain then exactly the wines I was going to produce and how I was going to go about it.”

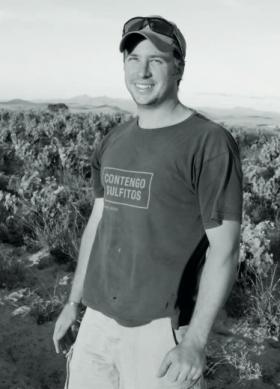

I visited Craig, Carla and family twice. The first time was on a trip for the entire sales team to South Africa in January 2014. We arrived in the Swartland on a scorcher, walked amongst the tiny ankle-high bush vines, whilst Craig darted around and popped grapes in his mouth. “Picking these rows next week,” he announced.

Eric was incredulous. The acidity in the grapes was puckering.

Craig smiled confidently. “It’ll be fine. I’m happy.”

We then went to the Observatory Vineyard. Craig had given the unkempt vines a new lease of life. “Pruning with a hangover on my day off!”

To the winery which Craig had imprinted with his personality. It was cool in every sense, ambient winemaking to a rock track score. In one room was a big cement open tank, at the bottom of which was a barrel. This was Craig’s notorious underwater wine. Again, Eric challenged him at every turn. What was the rationale behind fermenting wine under water? Craig shrugged and smiled: “Because I want to know what happens when you do it.”

Later, we tasted the wine out of bottle (as opposed to diving into the tank and sucking it out with a long straw). It was delicious, damned delicious. Eric narrowed his eyes. I could see him thinking: “This guy is crazy. But he is crazy in a good way.”

A Life in The Day of a Vigneron (2015)

No time to wallow in jet lag for it was out into the searing heat of noon to meet the toiling Craig. The previous day he and Carla had racked up 18 sweaty hours in the winery. [He was currently plying his craft at the old Observatory Winery, a compact building not that much larger than a garage with a dedicated barrel room and a small winemaking facility].

As I enter the cool respite of the winery I hear the second-hand destemmer chugging away near the entrance. It is a minimalist gizmo-free environment; in the far corner against the wall are a couple of big plastic tubs where the destemmed grapes are loaded from a receiving tray (scooped in with a bucket and cupped hands), whilst against the opposite wall a medium-sized stainless-steel tank wherein the Chenin has already begun its super-sudsy ceiling-to-flor ferment. On the left and through a low doorway into the relative gloom of the barrel room where each of the barrels is awaiting the bounty of the new vintage. Already chalked on the heads are the names of the cuvees: Cortez, King of Grapes, Redemption, Serenity and Mangaliza (which we might call “the pork barrel.”)

Carla is already busily washing the lug boxes or caisses in a plastic bath. Each one has to be cleaned of leaves and other grapey detritus and subsequently stacked in threes in the sun to dry. Craig, meanwhile, is scrupulously hosing down all the equipment. “I don’t want a single grape on the floor.” “I love tidiness in the winery. Winery work is 90% cleaning”, he laughs ruefully, as we enjoy a refreshing beer later. Being so hands-on gives one an intimate, almost visceral relationship with the wines.

Often Craig is taking apart bits of equipment and reassembling it, cudgelling, cajoling and cursing. Instinct and experience are the guides when the little things become the major irritants.

Whilst much of this may seem like common-sense this is winemaking at the fine margins, requiring a modicum of luck as well as good judgement. For want of a screw – or a screwdriver – the whole process can grind to a halt. A power cut (and there are many) or a broken piece of machinery means that you are reliant on others which is not easy when you pride yourself on your self-sufficiency. Often Craig is taking apart bits of equipment and reassembling it, cudgelling, cajoling and cursing. Instinct and experience are the guides when the little things become the major irritants.

A vigneron needs to be organised; having a clear idea in his or her head and sticking to it is paramount. He or she also has to multitask like crazy. Finally, it is essential to be adaptable and have a plan B and even a plan C. One poor decision or unforeseen circumstance will create a domino effect on the activities for the rest of the day, and when you are splitting your precious time between two wineries, borrowing equipment and needing to transfer your limited resources from one place to another, things can quickly spiral out of control.

After emptying the grapes into one of plastic tubs and giving Carla a hand cleaning the cases we stacked and strapped the crates and tubs on the back of a trailer with some wooden pallets. It is crucial to have the correct number of cases otherwise the harvesters who are paid by the box won’t be able to earn their full reward. We jump into the vehicle and bump along the dusty road, ferrying this cargo between the two winemaking facilities.

Craig currently buys the grapes from various sources as he works with a wide palette of grapes and is always looking for the best single vineyard expressions of the grape varieties in question. He works the old Observatory estate vineyards with the bush vines of Chenin (which goes into his clean skin Cortez Chenin), Muscat (making the skin contact Sweet Cheeks) and Harslevelu (possible wine next year). Grenache and Syrah come from another farm around 20 km away. The other grapes come from vineyards adjacent to their current home. All are farmed organically, using manures from their small herd of cattle.

After dropping off the plastic tubs and the cases we drive back to the other side of Malmesbury to look at some of the vines that Craig is renting from a farmer. The grapes look good, the terroir is koffie klip over clay. We walk along the rows, examining the bunches. The land belongs to a farmer that Craig can trust to work in the right way, rather than one is who going for the highest yields.

Craig is a perfectionist. He counters the myth that natural vignerons embody the lazy in laissez-faire. Contrariwise, this is intense stuff, hands on, fingers in, white knuckles everywhere – nuts and bolts as well as logic, intuition and timing. What we may eventually taste is a romantic lover’s meeting at the journey’s end, but the wine does not happen by accident. Nor is he afraid to change his approach – according to the vintage, according to the vineyard and according to the matter within the grapes. Decisions and revisions. The empirical natural approach. He is still finding himself in this regard, and still discovering the wine. When you are a vigneron you are happy to celebrate the differences in all your wines – they are your children, so to speak, for all that.

We love Craig because he reminds us of us of simple truths. He started making natural wines to satisfy an urge and soon discovered that these were the wines close to his heart, wines that challenged him, but also the wines that he wanted to drink. He has moved from being shy to having confidence in his opinions – without ever sounding cocky.

Get to know Craig better, and in his own words. Check out our Q&A with him HERE.

Read the third and final part of Chapter Three here!