The cuckoo in Wordsworth’s poem heralds the coming of spring, and whilst the cuckoo chants her merry song, one may also discern a more discordant vernal sound – that of a winemaker or critic exploding messily into print about natural wine.

This is a subject that lies dormant over the winter months, but, as the sap rises and animates the foggy brain matter, critical opinions burgeon in order to bombinate in the vacuum of wine magazines.

The mutterings are the undammed rage against the lack of the machine, the idea that wine can become popular without the tools of marketing, without the appliance of science, without the imprimatur of panels and focus groups. It is raging against the freedom to choose, against the viral impact of social media, where individuals are free to like what they like and advertise what they like.

The latest attack piece came from someone from a winery that makes some of the most pluperfectly anodyne wines that it has ever been my dubious privilege to taste. When milquetoast is too strong (or weak) a word to describe a wine as thin as the homeopathic soup that was made by boiling the shadow of a pigeon that had starved to death, then you have this winery’s Pinot Grigio. There are worse wines, admittedly. This PG adheres to a commendable Platonic ideal of dullness that is remarkable, and effortlessly encapsulates anti-beauty and non-originality with exquisite precision in a bottle. It is functional, to say the most. Robotic wine was created to serve a purpose – to be faultily faultless, icily regular, splendidly null – and all to a price point. Real, natural wine comes from a vineyard, a person, a feeling and a series of natural transformations. It was born to live a unique life.

Challenging orthodoxy is healthy in that it sets debates in motion and serves to change habits.

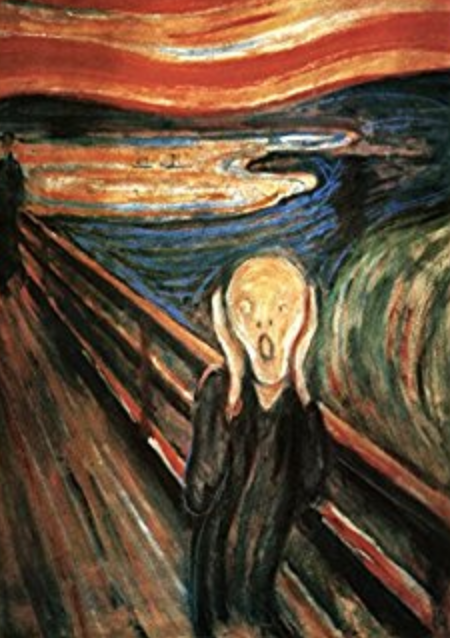

There are various plausible explanations as to why certain people might explode in baleful wild verbal ferments. I would love to blame the biodynamic calendar and cyclical lunar influences for such hairy-faced behaviour. I rather think though that some commentators feel threatened, as if you were about to remove one of the building blocks of their philosophical universe. The idea that there might be more things in heaven and earth etc than their narrow world view could encompass is unconscionable. When having a pop, science is invariably invoked, by critics of natural wine, as a kind of moral arbiter. Like zealots citing Scripture. Natural wine = bad science. Equals wrong in every way. Equals QED. Science is not, however, about using chemicals as voodoo silver bullets to cure faults in wine, it concerns the knowledge that we gain from sensitively observing nature. It is not about knowing the chemical formulae behind transformations and being able to recite by rote what goes on at an atomic level, it is about knowing in your mind, and feeling on your pulses, what is necessary to help to make wine that tastes alive, that captures the song of the vineyard.

Those who believe that all is for the best in the best of all scientific universes, and believe in controlled outcomes in winemaking, often subscribe to other forms of economic and political control in their world view. They might believe in the power of the brand, or the inevitable passive acceptance of the consumer to the stimuli of marketing gimmicks and perceived trends. The world is their petri dish. The natural wine phenomenon is a curse for these people – for starters, its proponents view wine as a healthy, natural beverage (look, no additives). The consumers of natural wine are wont to interrogate the provenance of what is in their bottle – the farming methods that realised the grapes for the wine, the additives that have been used to alter or modify the colour, flavour or texture. The desire for additive-free food and drink is not a bad thing! Challenging orthodoxy is healthy in that it sets debates in motion and serves to change habits. But it does undermine certainties, such as there is a correct way of making wine, that wine is a standardised product that must be deemed clean and correct by a panel, that without such eternal verities the world of wine and its unwitting consumers would be thrown into endless confusion.

It is possible to divide the anti-natural brigade into various categories of hydrophobic reactiveness. Firstly, there are the panjandrums, loftily dismissive of the phenomenon. They feel irked by the existence of natural wines but would rather not lend credence to them by engaging in a war of words. Dignity forbids. Their palates are attuned to a classical wine-style, so will never appreciate (let alone taste) greatness in a natural wine. The same might be said of those who can only listen to one style of music or enjoy one school of painting.

Most wine is thoroughly denatured, as rather than being a microbiological transformation of grapes and native yeasts into alcohol, it is for the very most part, a succession of chemical interventions, which, by seeking to clean up the juice, serve to filter out any trace of individuality.

Others prefer to explore different avenues of attack. Primarily, they find the semantic connotations of the word natural troubling, as they feel it endows a group of wines with a sense of smug moral superiority. They also object to the word as they believe wine can never, by definition, be natural, because all farming is an intervention, as is all winemaking. The wine did not make itself, ergo it cannot be natural. Quibbling about nomenclature is a trite way of looking at wine when one should be focusing on practice. Most wine is thoroughly denatured, as rather than being a microbiological transformation of grapes and native yeasts into alcohol, it is for the very most part, a succession of chemical interventions, which, by seeking to clean up the juice, serve to filter out any trace of individuality. Natural wine simply seeks to preserve as much as possible the nature of the fruit and the sense of the vintage. The vigneron is not there to alter or compensate but to help to give birth to something. It is the difference between translation and interpretation on the hand and intervention and imposition on the other.

The problem with so many of the contra-natural wine arguments is that they are constructed on base generalisations. The one-wine-fits-all-approach. People, whom I regard as very intelligent, will tell me an anecdote about natural wine they have tasted or, for example, excoriate a sommelier who has proposed something obnoxious to them (in their opinion) and use that as a justification for a wide-ranging critique about the subject. They will speak airily of a natural wine movement and describe a kind of fundamentalism towards the subject that would be alarming – if it were remotely true. It is patronising to assume that people are being seduced by an idea, that they have surrendered up their ability to taste because they are dazzled by the trend. People drink wine for a variety of reasons: to consume something nourishing or tasty or try something which tastes different. Something gastronomic. Something lighter. Something alive. Energetic. Fun. We know that our palates change – who would have thought that orange/skin contact wines with their unusual and often challenging tastes and textures would prove so popular?

We can’t pretend there isn’t a political dimension to the consumer choices we make. Those who seek out natural wines are more likely to care about organic farming and responsible environmental practice. They may also feel that there is a strong case for transparency in wine labelling. By choosing to drink natural wines they are not being persuaded by the authoritative opinions of professional tasters and wine critics. They care more about the grower and what the wine tastes like. If the grower doesn’t receive the appellation for his or her wine, or chooses to leave that appellation voluntarily, the natural wine drinker does not mind. Appellation is not perceived to be about authenticity or holding a mirror to good practice, as it should be, but has come to be seen as a guarantee of (common-denominator) consistency.

As I have said elsewhere, the battle for natural wine legitimacy was won years ago. When the first natural wine producers (re)surfaced in the mid-1980s they and their wines were on no-one’s radar. Twenty plus years on and natural wine culture is endemic: the biggest artisan wine fairs in the world (in every country), countless importers, wine bars, sommeliers, bloggers and, of course, hundreds upon hundreds of growers. This movement, if we can call it that, has been fuelled by social media, widespread travel, work placements, a constant process of exchange. It is what so many growers are doing and people are drinking that we barely need the word “natural “any longer to describe a vine-growing-and-winemaking philosophy that seems intuitively right. Nor is natural wine a static philosophy or approach to winemaking, but rather it is as fluid as the wines themselves and the thoughts and feelings of the people who make the wines.

It is patronising to assume that people are being seduced by an idea, that they have surrendered up their ability to taste because they are dazzled by the trend. People drink wine for a variety of reasons…

I am always puzzled when individuals now go out of their way to climb into the virtual bully pulpit to have their rants. Their histrionics invite laughter rather than respect, for the simple reason that they are constructing straw man arguments against invisible opponents based on fundamental misapprehensions and gross generalisations. Whilst that may add to the gaiety of nations it does not add to the sum total of human knowledge. A few years ago, there was a discernible climate of suspicion in the wine world. When I first started presenting natural wines to professionals I was treated like a callow whippersnapper trying to sell them a pup. These professionals felt that the wines were solely being marketed to have a kind of cultish appeal and that they were basically… crap. The cliché “emperor’s new clothes” was given more airings than was healthy for any cliché. The first part of their contention was wrong (marketed? Really??) and the second was surely a matter of opinion. As we have seen that opinion is not shared by hundreds and thousands of consumers. In the end you agree to respectively disagree and continue drinking what you like. The proponents of natural wine will sell their wines, will open their wine bars, will put on their producer fairs, and those who write about the subject will tell the stories and give their assessments. Plenty of people will make a living from the wines, and, believe me, if the whole thing was con, and the wines were little more than vinegar (as some would have you believe) then all the abovementioned enterprises would fail. And then the wine cuckoos would be chortling.

Such an enjoyable read, like watching an ice cream held up to the sun. So well put!

Thanks, David!