It’s not just dog eat dog. It’s dog doesn’t return other dog’s phone calls. (Woody Allen)

Morals? Can’t afford them guv’nor. (Alfred Doolittle, Pygmalion – George Bernard Shaw)

Those are my principles and if you don’t like them I have others. (Marx, Groucho)

I was musing the other day how there is often a disjunction between the way we conduct ourselves in our private and social lives and the way we do business. Business is a Darwinian environment, where sentiment is absent and exploitation is rife. Bad practice is not only accepted it is actively encouraged. What is also striking is that when certain people behave with an iota of propriety they are lauded to the skies for it. Multi-national corporations and supermarkets receive awards for green initiatives or ethical behaviour. Credit where it is due although ethical behaviour should be the sine qua non of every business. Examples of good corporate practice also ignores the less appealing aspects of big business behaviour: from encouraging over-consumption (and thus exploitation of the planet’s dwindling resources) to pushing their suppliers to the limit by screwing down the prices, late payment and throttling with red tape.

I strongly subscribe to the Golden Rule, which underpins the teachings of every single major religion on earth.

The Golden Rule or ethic of reciprocity is a maxim, ethical code, or morality that essentially states either of the following:

- One should treat others as one would like others to treat oneself (positive form)

- One should not treat others in ways that one would not like to be treated (negative/prohibitive form, also called the Silver Rule)

The Golden Rule is arguably the most essential basis for the modern concept of human rights, in which each individual has a right to just treatment, and a reciprocal responsibility to ensure justice for others. A key element of the Golden Rule is that a person attempting to live by this rule treats all people with consideration, not just members of his or her peer group. The Golden Rule has its roots in a wide range of world cultures, and is a standard different cultures use to resolve conflicts.

“Here certainly is the golden maxim: Do not do to others that which we do not want them to do to us.”

Zi Gong asked, saying, “Is there one word which may serve as a rule of practice for all one’s life?” The Master said, “Is not RECIPROCITY such a word?

—Confucius, Analects XV.24

Alternate “Golden Rule”

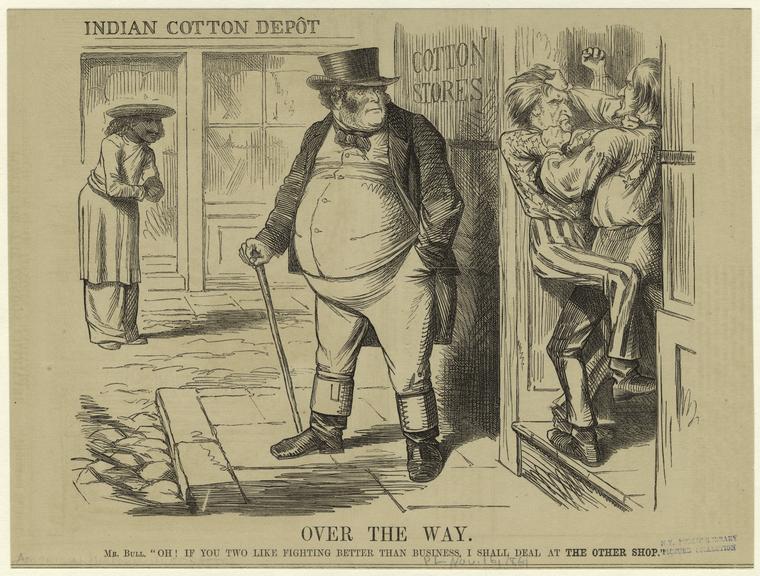

An alternative, more realpolitik definition of the “Golden Rule” cited in business and politics, with a distinct twist on the expected religious/moral definition, is “He who has the gold, makes the rules.” Citation of the Rule under this meaning is often meant to make a naive, weaker party aware of the dynamics of an interaction in which one party has greater resources and therefore greater power than another.

Why shouldn’t businesses adhere to the Golden Rule? We hear of good business practice, but is it possible, in the real dawg-eat-dawg world, to run a business holistically and economically effectively at the same time? I am inclined to think so. What holds people back is their distrust of others, the feeling that they are going to be stabbed in the back, or the front, and the over-cultivation of a sense of self-preservation and the profit motive. Most businesses are structurally set up to chip away at costs in order to improve profit margins rather than dedicating themselves to providing excellent service. To run a lean operation is an admirable objective, but when the cuts go through the bone into the very marrow of the operation, then the ethical foundation of the business crumbles. Without moral imperatives, partnerships are sacrificed, quality and passion – considered a sentimental distraction – are jettisoned, all of which leads to bad business practice which in turn fosters ill will, the loss of staff (who are the most valuable asset of any business) and the diminution of the product that the business is selling.

The Golden Rule can exist within the capitalist model, because it is to everyone’s financial advantage that we follow best practice and create a sustainable (by which I mean an ethical) economy.

Positive Reinforcement

“Each time you live up to the Golden Rule, your reputation is enhanced; each time you fail, it is diminished,” writes author and speaker Fred Reichheld in an article in Harvard Business Review.

As it turns out, rising above the situation and treating others decently is just as important in the business world as it is in our personal lives. A cut-throat business strategy may work at first, but as Robert Axelrod observes, over time it will, ironically, “destroy the very environment it needs for its own success.”

Building your business sustainably involves not stepping on others to climb the corporate ladder, treating your team, your customers, your vendors, and competitors fairly.

As wine importers (dealing with artisan growers) and as suppliers (dealing with restaurants, retailers and wholesalers) it is commercially sensible and ethically important for us to understand the business and livelihoods of the people that we are dealing with.

Henry Ford recognized the value of this simple concept. “If there is any one secret of success,” Ford is quoted as saying, “it lies in the ability to get the other person’s point of view and see things from that person’s angle as well as from your own.”

Scrunch or be scrunched – Mr Boffin, Our Mutual Friend

And so to prices and not just the recent currency surcharges but the principle behind any increase. These are not in the control of wine merchants but are influenced by two respective volatile climates – namely the weather and the economy. Upward pressures include, inter alia, the size and nature of vintages, the cost of raw materials, increasing transport costs, increasing wage costs and the (mis)fortunes of the pound against other currencies. Most suppliers will absorb the greater part of a price increase as they wish to remain competitive and not inconvenience their customers. You might think that those who purchase wine would appreciate its real value and also the market pressures that drive prices up (mainly) and down (occasionally). Adhering to The Golden Rule would involve customers understanding these economic rhythms and maintaining a loyal and productive relationship with their suppliers. This is not invariably the case, however, as business is inevitably auctioned off for money and suppliers seek to undercut each other in order to grab a diminishing piece of the financial pie. All of which sets a very bad precedent, for it creates adversarial relationships based on zero trust, leads to corners being cut, and goes on to affect the whole supply chain.

Challenging necessary price rises may be topical, but endemic behaviours include avoiding payment, not communicating intentions, not appreciating quality and not rewarding exceptional service. We all understand about cash flow and margins; observing The Golden Rule involves refining and even disciplining your business strategy, ensuring that you don’t bite off more than you can digest, whilst respecting the terms and conditions of a contract. If an arch-capitalist like Henry Ford can see the benefits of treating people in the business supply chain with respect, then others may wish to re-evaluate their business practice. In the final analysis, business is about people and not about numbers and spreadsheets. The most successful restaurants – in our experience – are run by people who care deeply about what they are doing. The businesses that go to the wall may have been started with the best of intentions, but eventually lose their way because the people that run them spend all their energy on making deals and cutting corners rather than focusing on what makes an enterprise really successful.

Pingback: The Thin Veneer of Civility: Non-Wine Thoughts for 2017