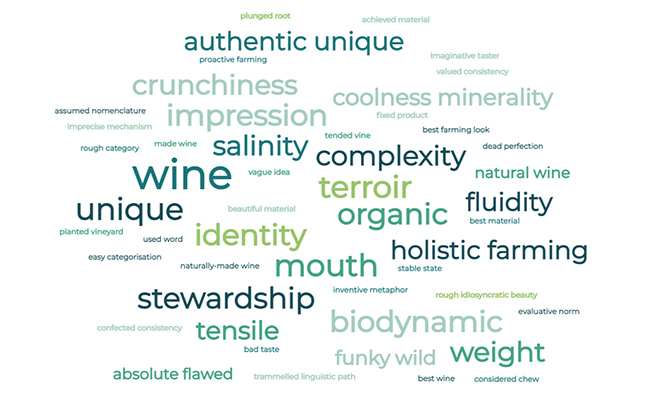

If I were to create a woolly word wine cloud to encompass the language I use when talking and writing about wine – and natural wine, in particular – it would surely precipitate a shower of fairly random terms, some that are recognisable and others that are obscure, somewhat vague and definitely personal.

I have grouped these into very rough categories.

Unique, individual, independent, singular, pure, real, identity, authentic…

This word cluster details that which we value about naturally-made wines. It refers to the idea of wines that are hand-crafted and of circumstances that cannot be replicated, and wines that should be celebrated for their singularity. The descriptors also stand as a political and philosophical response to a wine world where homogenous, pasteurised, industrial, commercial products still dominate and confected consistency is valued over real personality.

Flawed, wabi(sabi), relative vs absolute…

The determination of what is flawed and what may be faulty is certainly contentious. One person’s flaw may be another one’s fault. For the oeno-angelists, all flaws are inadmissible and they would outline a dichotomy between good and bad taste, right and wrong, accuracy and clumsiness. The wineyverse is not so Manichean, however, and the lines in the sand are not so clearly defined. There are both improving flaws, imho, and those that perhaps too cracked for purpose. I have written about wab-sabi elsewhere and suffice to say, that what gives wines their rough idiosyncratic beauty is not some notion of dead perfection, but rather the fact that wine is a living liquid, one that is evolving and not coldly compressed into a permanently transformed and stable state.

Farming, terroir, organics, biodynamics, regenerative, stewardship, holistic…

Wine is made in the vineyard. This is a wine truism. We are talking though about more than the means of production, such as irrigating vines to produce grapes to yield the material to make a fixed product. This is fundamentally about the region, and the very particular place where the vineyard is planted, the soil below and the sky above, the nurturing of nature, the way the vines are tended in order to express the best/truest sense of that place in which their roots are plunged. The methods by which the best material is achieved and vine strength enhanced, involve various forms of proactive farming with respect for biodiversity paramount in the equation. Farming is an environmental prescription and the best farming looks to the long term, always replacing (and more) what it takes from nature.

Wild, native, free, liberated, natural, raw, mutable, funky…

Some of this nomenclature is assumed by artisan wine fairs, wine companies and natural wine bars to illustrate the philosophical overtones of naturalness. When it describes the specific winemaking process, it highlights the low-intervention approaches and those transformations that occur naturally without the corsetry of chemicals and a battery of oenological trickery and tropes. The wines themselves are without maquillage, they may be also protean, restlessly shifting in the glass or decanter, defying easy categorisation. And the vigneron(ne) is the accompanier and the midwife, nurturing the wine to a form of self-realisation, endeavouring not to denature the beautiful material that the vineyard yielded. In terms of taste, we have a vague idea of what “funky” is (although like flawed, there is a spectrum of funkiness), although liberated, natural and raw are more to do with a feeling about the wine, that it is both elemental and fine at the same time, that the primary sensation is that the wine expresses to its utmost something of origin and not at all that it has moulded into a specific shape for a specific purpose. The zero use of sulphur, sans safety net, for good or bad (that’s another argument) allows the wine to be unchained.

Textured, weight, impression, mouth-filling, layered, complexity…

Wines may describe many shapes in one’s mouth. Some are as fine gliding lines, while others have amplitude. These words are used when the wine warmly spreads out and coats your mouth, bathes your tongue, gums and teeth. These are the wines that you are reluctant to swallow instantly; they deserve that extra considered chew.

Minerality, salinity, flinty, crunchiness, nacreous, coolness…

Minerality is a taste impression associated with terroir and the origins of wine. It gives the wine its unique (that word again) accent. Are we tasting rocks and stones or a form of mineral salts (in the same way that we might taste minerals in mineral water)? Minerality confers a defining element to the wine in question, providing its bone structure, if you like. The impression of minerality can be intensified by reductive winemaking or low ph, but in the end it is probably a combination of the properties of the vine and the soil and a vigneron who understands how to harness the latent energy.

Nerve, tension, tensile, dancing, darting, ricocheting, coiled, reserved, energetic, fluidity…

These are some of the tactile qualities that excite us when we taste natural wines. We are talking here particularly about the kinetic properties and potential of the wine, the oft interplay between holding back and release, a glissading quality as the wine courses across our tongues. It is the opposite of the fruit explosion. It is linear. Or linear + an x factor.

—–

Language is an imprecise mechanism with which to describe all the subtleties encoded in a glass of wine. A scientific taster would dutifully record their impressions with a dispassionate “camera eye,” creating a kind of digital photofit version of the truth. The words would be satisfactory in themselves, concrete equivalences, evaluative norms if you like. Everything calibrated and verifiable. Words striving for objectivity.

An imaginative taster would bring their baggage to the party and deviate from the trammelled linguistic path by approaching wine in a more subjective way. Feelings would be evoked; shapes would be sensed, pleasure would be expressed, energy would be tuned into. It would be fuzzy, a word-gallimaufry.

The best wines encourage us to reach beyond the language of the textbook. We may thus resort to inventive metaphors and similes and our own private lexicon of terminology (that perhaps we alone understand). I often say that I know what I mean when I utter or write words such as natural, wild, free, energetic and minerality as a form of shorthand for a group of descriptors. The fact that we can’t always precisely put our finger on a wine is something really to be cherished.