The other day I was asked to do a pithy tasting note for a somewhat bland wine (let’s be generous) for a pub list. As well as the difficulty of trying to remember what a wine tastes like that you haven’t tried since forever, it is also being in the mood to have the wherewithal to summon up a bunch of words that have not trampled into the oblivious ground by excessive use. Reader, I make my Merlot sound exactly like Pinot Noir. And somewhere in wine heaven, a whole bunch of angels clapped their hands on their seraphic brows and… fainted.

The (very) average tasting note is a cold template. Or derives from a Venn diagram of word families. Or is at the end of a flow chart of colour, aroma and taste options. Words in boxes. Or clouds. When I string the words together, I have various options, but in the end, in the interests of not being pretentious or über-graphic and frightening the horses, the note evolves into something abstract and quasi-objective. The wine could be anything.

Flashback. A minor minion-judge at The Decanter World Wine Awards, I am sitting here at a table in front of a flight of wines from Jurançon and Gaillac. It is about twelve years ago. I obediently churn through one wine after another. My first tasting note is a cornucopia of impressions, a ransacking of the hypothetical fruit salad bar. My second one itemises the remaining fruits in the galaxy. The third wine elicits some fuzzy catch-all wine terms. Thence to abbreviations (e.g. OTD = oaked to death) and finally a notation of ticks and question marks and emoticons. Having appended my impressionistic marks, I sit back, relieved to have negotiated another tranche of mediocre wines. Steven Spurrier suddenly appears in a puff of smoke, alights at our table and requests our marks, which we dutifully yield. He randomly selects someone from the panel to read out their notes. Each volunteered person has scripted a fluent WSET-wrought story, replete with trade-jargon curlicues. Spurrier then turns to me and asks for my considered tasting note for a particular wine. I glance down at my tasting sheet and realise to my horror that I have scribbled?! in lieu of coherent chapter or verse. I can’t even recall what colour the wine was. I improvise a verbal note with the most indeterminate terminology I can muster. The wine is varietally-correct, has appealing berry fruit character. Elegant and well-constructed, it possesses moderate-to-good-length. Steven smiles. Evidently, this is an ecumenical tasting note.

In the unlikely case that I am ever called again to testify about a wine, I have a couple of sneaky descriptions in my back pocket.

For a red, I would revert to pure Schildnechtia: “…displays a gorgeous, distillate-like herbal and floral profusion atop a rich, deep pool of ripe but fresh black raspberry and dark cherry, with resinous evocations of rosemary, fennel, black tea, and marjoram; berry seeds and cherry pits; as well as a tactile sense of seemingly schistic, crushed stone impingement and pungent smokiness, all leading to a finish of terrific tenacity not to mention a brightness, verve, and sense of levity uncommon for its vintage.”

Boomshakalaka! As the Goblin king (played by Barry Humphries) says when Gandalf stabs him in the stomach: “That’ll do it!” It would take a team of eager sixth formers a month of Sundays to unpick all the rhetorical tropes from this gravid prose, but I refer my honourable friend to the “seemingly schistic, crushed stone impingement and pungent smokiness” passage and doff my sincerest chapeau to this pluperfect platonic echt Schildnechtness.

Words are rough tools no matter how they are combined and with what kind of authority they resonate. Traditional wine descriptors such as “elegant,” “refined”, “varietally-correct” and so forth, cast an obscure patrician shadow over a past-time (i.e. drinking) that is essentially hedonic in nature. I feel like the worst offender in this respect. Language is made to fit over experience like a straitjacket. High-concept terms embodying classical notions of balance and proportionality, implying that every wine should conform to particular architectural precepts, create a remote hierarchy and places man or man’s system before the wine – as if the whole notion of taste was merely part of some Platonic classification.

When wine ventured into the televisual medium in 1980s and 1990s, its amusingly presumptuous language needed to become more demotic. Television would surely provide the platform to relate wine to the consumer’s experiences. The small amount of air time it was given, however, had the peculiar effect of infantilising the subject, whilst paradoxically making it even more obscure. Wheelbarrows of ugli fruit indeed! Talk about going off on a tangelo. Making wine-tasting sound fun may have been a good wheeze, making it over-ripe for parody… a kind of ignoble rot.

People in the mainstream visual media worry that wine is exclusive – and therefore pretentious. By reverting to a language largely composed of sound-bites they trample over the nuances of the subject matter. Wine has not been served well by the written word either; the lengthier wine columns in national newspapers have all but been pruned to nought by editors who are unable see the relevance of wine as a cultural phenomenon. Restaurant reviewers ignore the very existence of wine as a fundamental part of their meal, yet lavish detailed descriptions of every dish they taste. This sin of omission stems from an inability to talk familiarly about wine, as if its language was some kind of obscure dialect known to a chosen few. As for wine books (in this country at any rate), they are the rarest of birds and in danger of extinction, virtually consigned to the academic backwaters of the trade. A very few honourable exceptions apart, those that manage to get published tend to be contractual “rehashing” of existing work. Self-published and crowd-funded books now appear to be the only way to advancing the sum of serious and informed writing about different aspects of wine.

The counterweight to this is the burgeoning social media scene which has allowed self-expression and created a positive blogjam of uninhibited opinionation. Ideas may be freely explored without editorial restraint in the blogosphere. However, more writing does not betoken better writing.

Now there are thousands of wine reviewers out there – professional and amateur – people who desire to prove their expertise by tapping into the received linguistic wine discourse. Wine courses instruct their students in method, how to cultivate a rigid language of tasting notes and to objectify wine as if it were a liquid to decode in as prosaic a way as possible.

The point of words is to communicate impressions and share experiences, yet I rarely read an official wine description that chimes with my real experience of tasting wine. So many of them seem to be raided from the almsbasket of officially-recognised terms as if we all must feed from the same denominator of experience.

—–

When we talk about tasting, we talk about human reactions. To adapt Brillat-Savarin: Tell me what you taste and I will tell you what you are.

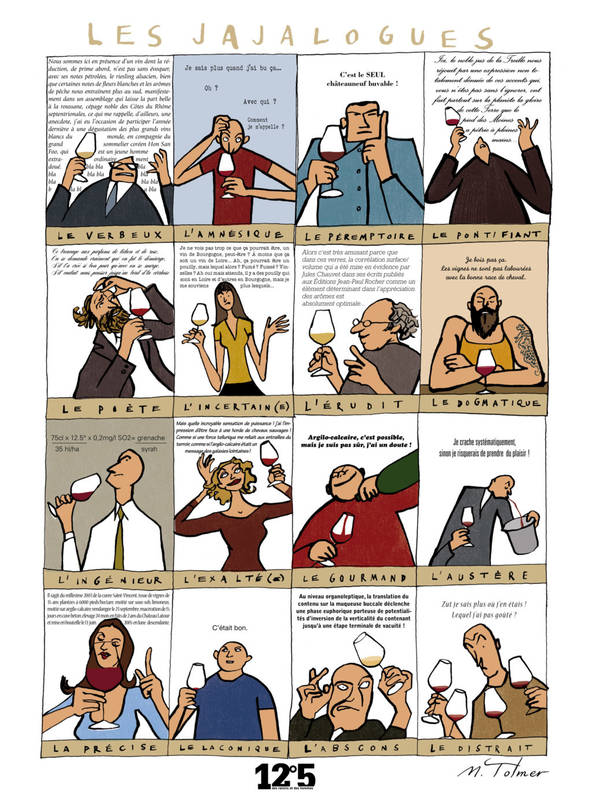

Our good friend Michel Tolmer brought out a wonderful poster last year. In French it is Jajalogues, in English The Moenologues, a witty representation of sixteen babbling and not non-babbling taste-archetypes from the natural wine world – and beyond. Or are they based on real people? Of course, they are – we’ve all met The Verbose, The Dogmatic, The Opinionated and The Laconic in real life, and, if we are honest, we see more than something of ourselves in these tasters.

“Les Jajalogues” by Michel Tolmer.

The Verbose. You know that guy – duelling on Bordeaux vintages; he raises your 82 with a 45. A Colt 45. He has put his wine girdle around the earth many times and met all the opinion-formers. He wears his pseudo-erudition like a clanking cow bell and will prattle on, contradicting himself regularly. He veers into verbal cul-de-sacs as he become intoxicated – with the sound of his own voice and perhaps with something else…

The Amnesiac. This guy – timid, and so overwhelmed at the possibility of getting it wrong that he disappears into his own mini-vortex of confusion.

The Opinionated. Stand back for the blast of unalloyed confidence. A man, of course, a man, who fixes you with a glittering stare (a monocle would add to the effect), grasps metaphorical lapels (his/yours), wags a large baton-like forefinger in your face and pronounces his own inalienable wine truth. You’ve been told.

The Pompous. Even more rarefied in his ridiculousness, another chap who loves the sound of his voice. The words may be beautiful in intent, but not in the way they are randomly strung together. For the pompous man, wine is the only art form, it is history and culture bound together, and perhaps only he has a direct line to its metaphysical profundity. In the end, his utterances illustrate that the cosmic potential of wine overwhelms even the most resonant attempts to describe it.

The Poet. Here’s a noble languorous fellow with demi-glazed eyes as he drinks deep from the Pierian spring, gives a quasi-consumptive cough and rhymes roses with cirrhosis. His words, aerial effusions soar, this noble inheritor of Rimbaud, only to fall with a thump to the earth as spiritual intoxication is subsumed by real intoxication, the heir of the doggerel that bit him.

The Uncertain. She drinks white wine. She knows it’s white, but its origin confuses her. There are Pouillys and there are Pouillys. But which is which?

The Erudite. His forehead is high and sloped, a phrenologist’s dream-playground. His glasses perched on the bridge of his long nose (what a schnozz!) make him look as if he is gazing into an endlessly deep font of knowledge. He smiles at something that only he understands, but something that he thinks is blindingly obvious to all of us. We smile back, uncomprehendingly. What on earth is he talking about?

The Dogmatic. A burly guy. He has a beard and a tattoo of some grapes on his left arm. The tattoo says Pinot. Do hipsters drink Pinot – surely it should be Pineau d’Aunis? Or maybe it is an ironic tattoo? French hipster-chic? He is magnificent, adamantine, a not-to-be-argued-with, holier-than-holy dude who will not deviate from the pure faith. He is Mr Triple Zero, who wears his hair-shirted vest with unsmiling pride. Yes, the plough horse must have provenance and the cow crap must be local. Nothing else will do.

The Engineer. He sees wine as the product of precise chilled mathematical construction in which everything is related to everything else. He takes no joy in this, but he approves of the harmony involved. Taste is irrelevant.

The Excitable. She has been reading too much DH Lawrence recently. The wine arouses her sexually and cosmically. It is making love to her. We retire and leave her to her effusions.

The Gourmand. He’s laconic. He will say something about the wine, because that is what is expected in polite company. But it is important to pour another glass to be certain. And then another…

The Austere. We all know the austere taster. The person who desires to be in the frigid taste zone, the human merciless-magnifier, who confidently believes that their palate is calibrated to be the perfect receptor of taste, and that their opinions are logical to the point of Vulcan emotionless objectivity.

The Precise. Her palate is refined to the nth degree and she is terrifyingly accurate in her analysis. Each sniff abstracts all the information from the glass and her memory, a computer-like repository of facts, sends back all the available data for her to make her authoritative Wine PHD pronouncements.

The Laconic. The laconic. C’est moi aussi. He likes it. I like it. It’s good. Enough said.

The Abstruse. It is not enough for some people to enjoy wine, but to dress up that enjoyment in the opaquest manner possible. Wilful obscurantism meets the need to be taken super-seriously. The guy is drinking wine, but he wants you to know that his drinking is elevated way beyond the usual realms of gustatory need.

The Distracted. The one who is so keen to compare and contract and conduct complicated blind tastings that he becomes terminally confused, forgets which wine is in which glass, what he tasted, and doesn’t know what the hell is going on any more.

Some tasters that you know are not confined to a single comic strip box. I am four or five of the above. At least. A lot of us like to channel both Dr Jekyll to Mr Hyde (two of my favourite wine tasters). And a miscellany of other equally strange characters too. We also may take our tasting colours from the company that we are with, in order to be more socially amenable. It does not do to evince levity at an en primeur tasting – get out the prayer mats and incense – whereas at the dinner party The Austere and The Engineer are not the most welcome guests. Wine tasting can be a patchwork quilt of every human action and reaction and emotion: social butterflying (Instagram); one-upmanship; confusion; humility; reminiscence; erudition and hilarity. From primal to aesthetic, from approving grunt to spinning a fine web of words.

Now back to that milquetoast tasting note for Merlot. Or was it Pinot? Make it pithy. Without taking the pith.

An accurate list you’ve got here! Though Domaine les Caizergues suggests one other: The Francophile. When the pressure of expectant party guests awaiting her “expert” verdict loosens her grasp of the English language, in a panic she declares that this particular Languedoc cuvée has notes of “Flaubert”.

To experience said “Flaubert” notes, order from Domaine les Caizergues today!