Unicorni-copia!

Look – don’t touch. In fact, don’t even look.

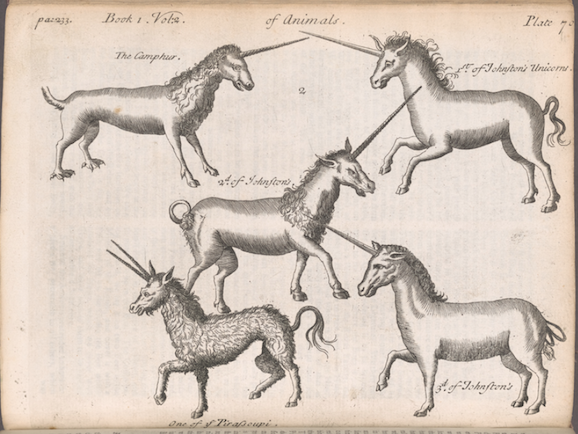

In European folklore, the unicorn is often depicted as a white equine – or goat-like – animal with a long horn, cloven hooves, and sometimes a goat’s beard. In the Middle Ages and The Renaissance, it was commonly described as an extremely wild woodland creature, a symbol of purity and grace, which could be captured only by a virgin. Its horn was said to have the power to render poisoned water potable and to heal sickness. The unicorn continues to hold a place in popular culture. It is still often used as a symbol of fantasy, or rarity and un-obtainability, and, somewhat jocularly, is now applied to rarer-than-rare wines, those that many cognoscenti have heard about, but never tasted.

Purity is a rare enough commodity, and a currency that we prize highly.

In natural wine terms, we would understand it in the sense of wines that are uncompromising, that possess brilliant, unyielding tension, that are probably without the distractions of funk or the presence of clunky oenological tropes. The intention of this wine is always transparent, the fruit and minerals are crystalline, any imperfections and flaws only contribute to its unique beauty. Well, that is my definition.

Purity, by itself, does not ratchet up the prices of such wines. Sheer rarity combined with perception of great worth, creates a market price, which in turn makes the wine in question become a shiny bauble in the grey market and at auction, a potential plaything for collectors.

How many (or how few) bottles makes a wine rare? Once upon a time, Cloudy Bay Sauvignon was so universally desirable that 1.2 million bottles couldn’t slake the world’s demand. The perception was that because the wine was allocated, it must be rare and therefore that gave it a certain mystique. The demand for brand, however, is not the same thing as the desire to buy the tiny hand-crafted production of a producer’s single wine, one that is entirely dependent on vintage, on the whim and feeling of the vigneron(ne), and the ultimate singular beauty of the product.

Knowing the journey, the circumstances of the unicorn wines in question, makes us appreciate the wine for what it really is. Price, or reputation, should never be what determines our response to the wine. If the wine is expensive, then that must be because of the sheer effort and cost to make it, rather than artificial demand ramping the price to a level that is as vulgar as it is unaffordable. Such wine is constantly traded, rather than drunk for pleasure, does not merit “unicorn” status.

The demand for brand is not the same thing as the desire to buy the tiny hand-crafted production of a producer’s single wine.

The allocation system creates an intense desire to possess something for which there is obvious demand. If you tell a person that they can’t have something, then they want it even more. It’s human nature. At Les Caves, our preferred course of action is to try to spread the love, to give as many customers the opportunity to have (or to sell) a particular rare wine. We are therefore dealing in crumbs. With more vintages being wiped out by terrible climatic events, with special cuvees needing to be blended into other wines just to make ends meet for the grower, those wondrous wines that celebrate the best of the vintage and the highest craft of the vigneron, seem to be rarer than ever. Added to this the fact that the market for such wines grows bigger and thirstier each year and that we are competing with many more countries for much less wine, at the same time as having many more customers wanting to buy the little we do have and you have a definition of the imperfect uni-corn-storm.

It is nigh impossible to keep the existence of unicorn wines a secret from the indefatigable Google sleuth. Give a unicorn bottle to one person and that fact will be broadcast around the world within a few seconds with resultant torchlight processions marching to your door demanding equal consideration.

The phenomenon of social media has also ensured that – in many cases – unicorns are a means to an end, to post about, and to generate likes, vicarious label-love, as well as biblically impure envy and lust. These posts are as if to proudly proclaim: “I have achieved the unobtainable”. They are part of the humorous gastro-pornography that pervades our media channels.

Unicorns are beautiful creatures; you do them a service by demythologising them rather than engaging in practices that perpetuate the holy (and wholly pretentious) pricing that makes them so elusive.

What of the wines? Does the reality always live up to the myth? At some point you need to pop the cork on your unicorn (unicork?). Exalted expectations are not invariably rewarded. Beauty is latent rather than immediately apparent, wine can easily disappoint, and you might not be in the right frame of mind to appreciate the wine. A wine that takes us unawares, that creates wonder and delight… is not this the unicorn that crept up on us in the forest, the magic we are seeking, the glimpse, the glimmer of something fine and pure, where no notion of value, no thought of label-snapping, interferes with our pure enjoyment?

There are unicorn wines where we have too few bottles to sell to restaurants in any meaningful way. The best solution is to sell to friends and ask them to share with their friends or to let our bars have the wines and ask them to sell the wine at a small very-friendly cash mark-up. This is not an exercise about making money off the reputation of a wine. Quite the reverse, it is about sharing bottles, restoring the wine back to its original purpose as social drink. Unicorns are beautiful creatures; you do them a service by demythologising them rather than engaging in practices that perpetuate the holy (and wholly pretentious) pricing that makes them so elusive.