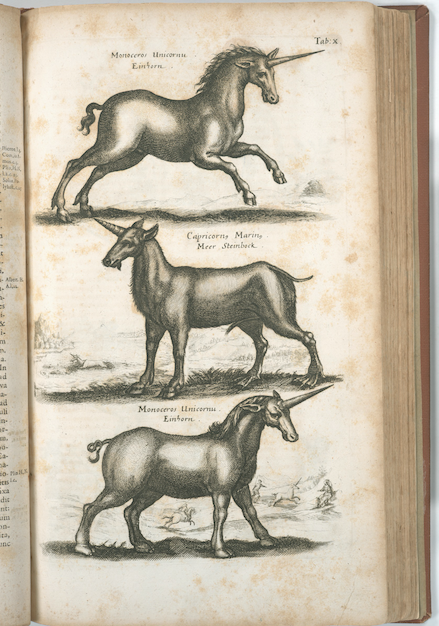

There are wines which are so rare because to make them requires nature to smile on the vineyard and for the vigneron still to feel that the quality of the wine justifies a specific micro-vinification of the grapes. These are the unicorns, the hens’ teeth, the unicorns’ teeth, even. Their beauty arises from their singularity; when you drink them, you don’t feel that you are drinking one of a series, but one of one.

2015 PM Mitohnealles, Andert-Wein

Scroll back a couple of years to my first trip to Burgenland. We were taken to the small plot of vines that comprise the Gemischter Sotz, a field blend of various white grapes. The location of the vineyard is in itself unremarkable, being a flat piece of land that was once under water (the marshes around here were drained some time ago) although some of the boggy, low-lying areas still host an extraordinary variety of birds. This small vineyard is humming with life. They have installed a box in a lone tree at one end of the row of vines for falcons to nest in. Herbs and grasses grow bountifully– spring onions, leeks, fennel, wild garlic, oregano and countless other herbs, edible (as it turns out) flowers and weeds. Michael stops and stoops occasionally plucking a plant and enjoins me to nibble this flower or that leaf. Whether it is the effect of the sun beating down and the earth warming up but even the bitter leaves taste nourishing. Pesky deer are kept away by the old-fashioned expedient of a wild boar’s hide draped over the wires. A flock of mixed sheep (including a rare local breed) are grazing in neighbouring pasture, whilst cockerels, guinea fowls, ducks and geese gabble loquaciously in the adjacent pen.

Michael repairs into a hut and brings out a loaf of sourdough bread – baked by his neighbour – a water buffalo wurst and some homemade wild boar prosciutto and we have an impromptu picnic of meat, herbs and edible flowers washed down with a wine that feels like it had sucked up the very lifeforce from the soil.

The wine in question was rich, golden-orange with a sweet-salty smell and then a nose of wild herbs, honey, sun-burnished fruit. It was – as they sometimes say – the wine of the moment. This is, Erich said with a smile, our PM – our Puligny-Montrachet. Penetranter Mistkerl.

We yearn to recreate such vivid moments, and certain wines have the capacity to dial a hotline to our memory banks. The other day I revisited PM (the 2015 vintage) at Brawn, where I was having lunch with Chad Stock and Bree Boskov MW. The wine had been sitting in a carafe for around twenty minutes and the colour seemed to be changing subtly by the moment as if animated by a response to the very light of the day. A burnished sunset of a wine, its deep hues were captivating, glowing, almost throbbing with primal energy.

The nose, or whatever we choose to call it, was (sweet)meaty and a little bit smoky, the palate is smooth and almost velvety with suggestions of pink grapefruit, yet also salty with a bitter almond note on the finish. A wine that sits on the mother of lees and skins, starts off tightly wound in its own skin, its aromatics initially reserved, then gently exudes a kind of warmth as of orchard fruit baked with sweet spices in the oven. And all Andert’s wines have a faintly medicinal bitter, fennel-inflected after-taste. This may to be do with the fact that the vines share their space with wild fennel and many other plants and herbs that have the same anise profile. They also possess what we like to describe as “natural energy”. Easy in themselves or with a relaxed intensity, not inviting judgement, but utterly and vitally redolent of the vineyards from which they are born.

And the grape variety of the PM? Petit Manseng.

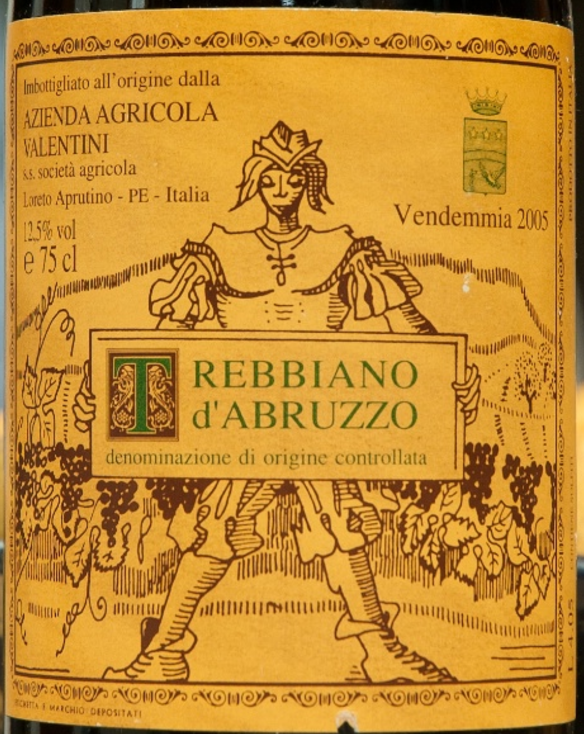

2003 Trebbiano d’Abruzzo, Valentini

And then we drank the Trebbiano d’Abruzzo from Edoardo Valentini, a man once known locally as the “Lord of the Vines.” This resolute old-timer, when he was alive, always disregarded all modern conventions and wrapped his operations in a shroud of mystery, fervently guarding his production techniques from outsiders. His Trebbiano took on uncommon colours, aromas, depth, complexity, and ability to age. Valentini’s wines always display a startlingly natural character, their individual quirks only enhancing their profound charm.

The Trebbiano d’Abruzzo seems to hail from another planet; no-one has a clue why the wine is the way it is – we’ve found that its optimum drinking period is 10-15 years from vintage. Francesco, Edoardo’s son, expounded his theory to us. In the 1950s with the industrialisation of the Italian wine industry, the Trebbiano Toscana was imported into Abruzzo to supplement the local version. Being a more robust, high-yielding variety with bigger grapes it eventually entirely replaced the indigenous Trebbiano of Abruzzo (and thus became known itself as Trebbiano d’Abruzzo). The Valentini family, using records dating back to the 1860s, discovered the properties of the original Trebbiano and using massale selection (over a period of 40 years!) in one vineyard of 2.5 hectares have essentially recreated the old Trebbiano with all its unique qualities.

Indigenous grapes, the channelling of terroir, espousing singularity and identity, the rediscovery of traditional techniques (of farming, of winemaking), all give colourful diversity to the often-monochrome world of wine where commercial relevance and reputation are continually bruited. The grape variety itself is one small element in a larger picture. Respected, and linked to its place of origin, its purpose is more than a functional “varietal”, it is that which provides cultural variety, embodying the very specific DNA of the locale and the growing season.

That Valentini’s wines from Abruzzo excite even more debate (amongst the privileged few who have sampled them) is a rare quality in itself: to some the wines are a testament to passion, obsession, individuality and purity, a reconnection to terroir, to others they are “quasi-defective”. One journalist told me that the Trebbiano gave her “goosebumps”. (Good goosebumps!) The great thing about Valentini’s wines is that they are constantly changing in the glass, shyly revealing then retreating into the shell, always suggestive, never obvious, inevitably very mineral, certainly very strange – and, because they are released with bottle age, they exhibit intriguing and offbeat secondary and reductive aromas. We are inculcated to respect transparent cleanness, and to accept the notion that a wine that is not clean must, ipso facto, be faulty. This view is an immaculate misconception. Some of the greatest wines are borderline mad and downright impertinent. The genius of the wine that does not surrender its secrets in the first aromatic puff is also often missed; I suppose if people want absolute consistency they won’t venture beyond the tried and trusted; if they want to be touched by greatness they will risk drinking something that defies easy categorisation. We tend to search for exactitude in wine that does not exist in nature and evaluate it by a pernickety sniff and a suspicious sip. Wines, however, can evolve, or change in context; you can no more sip a wine and know its total character than look at one brushstroke of a painting or hear a single musical note in a symphony and understand the whole. In other words, with certain wines, we have to drink the bottle, to see if our initial judgement was correct. And the truth can be hard to drink.

The wine, best after years in a cool cellar, shows a kaleidoscope of flavours that are creamy and crisp at once, ranging from freshly toasted hazelnuts to coconut shavings, and has an underlying bracing acidity that lends it an uncanny capacity to age. But let’s pour a glass of this beautiful wine and test the evolution. Give it a little time to open and out comes that elegant, minerally nose with ripe citrus aromas. Take a sip and experience how full and mouthfilling it is, how piquant and almost fat (but not quite). Note how refined the flavours are, how intensely they are rendered by its swathe of acidity, the sort that gives wines like this great potential for improvement with age. Observe how long the minerally finish is with its notes of hazelnut and liquorice. Today, the wine was not so shy; it was fluid and free with a lick of honey, beamish and agreeable. Young, but not in a nervy, wrought way, but in peak athletic condition.

2014 Bourgogne Aligoté 1902, Alice & Olivier de Moor

This wine is made from very old vines – vines that are unusual because they pre-date the ravages of phylloxera. The vineyard is near the village of Saint-Bris-le-Vineux and covers just half a hectare. The records show that the vineyard was planted in 1902 – hence the name.

Fermented and aged in old oak, this an Aligoté to age, extremely tight and high in stony acidity with citrus fruits and herbal aromas, very dense and long. This winespeak does not do justice to a wine which shimmers with authority – it has dense – or intense – transparency in the way that only wines with “perfect pitch” acidity can seem to glisten. Then the nose – glacier water buffing up a river stone, gorse flowers drenched with sea spray, all nostril-arching brilliance and then into the palate – linear, citric (juice plus pith), tears-of-chalk-stony, with tensile strength and just a smattering of lees spice. Liquid steel, this wine is an exhilarating skate across the palate. To coin a phrase, it takes you hither and Yonne.

2013 Bruyere Houillon Chardonnay La Chaux

Renaud Bruyere and Adeline Houillon started making wine in 2011 from vines located on one of the highest plots in Arbois – in that year a grand total of 250 bottles of red and 700 bottles of a white blend were produced. They have acquired – through buying or renting – some more vines since then, all of which are being converted to the biodynamic farming they implicitly believe in. All the wines are vinified barrel by barrel to reflect the terroir, the grape and the vintage with nothing added whatsoever. Everything is done in used barrels and the wine is topped up.

This is their simple philosophy in their own words:

Nous pratiquons la Biodynamie (sans certification) par idéologie et par « conviction ». C’est une science « unique » propre à celui qui l’exerce. Tout s’inscrit dans l’intuition du moment. C’est une part d’infini qui se dévoile au vigneron attentif!

Pour poursuivre ce cheminement, et respecter le travail d’une année, nous essayons de vinifier de façon naturelle sans aucun intrant, des vendanges à la mise en bouteille. Nous avons Foi en notre population de levures, et voulons un Vin Vivant!

L’objectif est de trouver l’équilibre entre le terroir, le cépage et l’année. Ces trois éléments conditionnent un vin, l’art du vigneron est de composer entre ces différents éléments avec le Plus et le Moins que peut apporter un millésime.

Beautifully clear green-gold white, delicate aromas of churned butter, almond-blossom and sun-ripened apricot skins, lively yet contained on first sip with a leesy prickle, proceeding to dance across the palate with real energy and finishing with an apple-and-citrus snap. Freshness, fluidity, vibrancy and delicacy – a wine that is harmonious and completely comfortable with itself. Living wine.

2014 Fleurie Ultime, Yvonne Metras

Perched at the top of La Madone, whisper it not, are some of the vines that make the Yvon Metras Fleuries. Like Voldemort we do not dare say their names (oops, already done so). These are wonderfully pure, but difficult-to-know wines. And even more difficult to buy. We will bathe in their symbolic glory.

1988 was the first vintage vinified by Yvon Métras at a family domain run by generations of winemakers. He withdrew from the cooperative winery to join the gang of Jules Chauvet’s followers whose leader was Marcel Lapierre. The way the 5-hectare vineyard is cultivated is the same as that of the other disciples: no chemicals, ploughing, severe pruning, low yields and exceptional terroirs with iconic parcels like “Grille Midi” or “La Madonne”. It’s from these parcels that he sometimes vinifies the “Ultime cuvee”, a wine that greatly contributed to his reputation as a top winemaker. Needless to say, the perfectly ripe grapes are hand-picked and vinified with whole bunches before undergoing semi-carbonic maceration. This older vine Fleurie has stones for bones, gripping granitic minerality that chisels the straightest of lines across the tongue. And the merest suggestion of cherrystones and gooseberries. Don’t expect any change from this wine unless you serve it from the carafe.

Ultime is the supernaculum from 120 + year old vines, a wine that needs to tarry awhile in the Seven Sleeper’s Den before you take your date with density (sic). Sometimes, to paraphrase Nicolas Joly, it is more important to be true than to be beautiful. Or to be nice. Or to be understand. The challenge of challenging wines is to find the right moment when their granite physiognomy cracks (a little), to have patience and allow the wine to come to you. Ultime is like reaching the summit of mountain, expecting jaw-dropping views and finding the panorama shrouded in mist and cloud. And then, one time, for a few instants, the mist melts and all is revealed.