Weingut Jurtschitsch is a very important winery in the Kamptal, with a rich history. The press house is from the 16th century and they have an enormous 700 year-old natural, cool cellar that used to belong to a monastery. Here you can wander through almost endless passageways with an extraordinary array of barrels and foudres (one was 27,000 litres!), glass demi-johns, small terracotta qvevri and (pride of place) a beautiful ceramic egg. The atmosphere here is tranquil; this is a place where great things can happen.

Having being run by the three brothers Edwin, Paul and Karl Jurtschitsch, the family-owned winery has now been passed on to the younger generation, to Alwin Jurtschitsch and his partner Stefanie Hasselbach. This family business succession has been prepared thoroughly. The couple travelled around the world, gathering experience in New Zealand and Australia, most notably with James Erskine in the Barossa. Working as interns in famed wineries in France, they got to know the French school of the Old Wine World. They had terrific fun and learned a lot. Now, they feel they can put the ideas and the experience they have accrued into practice back home in the Kamptal. When you talk to Stefanie and Alwin there is a twinkle in their eyes – they are constantly bouncing ideas off each other.

A first step was the change-over to an organic cultivation of the family-owned vineyards. They farm organically not only for the wines they are making today, but also to preserve their vineyards for future generations. They are best known for their single-vineyard wines that are fermented with their own wild ambient yeasts and gentle, traditional vinification methods.

Alwin would consider himself to be a scientist but he starts with a holistic (and environmentally-conscious) ethos. He observes the vines and understands the importance of a long-term approach in the vineyard. He and Stefanie reduced the number of wine-growing sites so that they could concentrate on the first-class appellations of the Kamptal. But all was done seamlessly with a great deal of sensitivity and respect for tradition. The wine philosophy also underwent a transformation: “Our wine style became more ‘polarising‘, characterised by the idea of terroirs without compromise”, says Stefanie Hasselbach.

They produce wines which let the vineyards and soils speak for themselves, even about the winegrower who cares for them. “Yes, we are farmers”, Alwin Jurtschitsch stresses, “this is our work, our tradition and handcraft in the best sense of the word.” In the cellar, all this is turned into a work of art. The Grüner Veltliner wines interpret the Kamp Valley’s spiciness at its finest, while the Rieslings impress with their crystalline minerality. More on these anon.

Alwin and Stefanie took us on a swift tour of the Heiligenstein vineyard. This steep Austrian hill is one of the world’s great Riesling sites and merits the abused epithet “iconic”..

Whilst voguish Grüner Veltliners thrive on the loess soils lining the Danube River, wherever enough primary rock reveals itself (as we saw with the Arndorfer vineyards) that becomes a preferred location for Riesling. The Austrian climate is decidedly continental; it’s colder in winter and warmer in summer than in Germany, for example, and the grapes can get significantly riper. Sweet Austrian Rieslings do exist, but generally speaking, the national style is dry, with the extra sugar fermenting out to produce more alcoholic, fuller-bodied wines. The Austrian government’s moratorium on chaptalization and strict yield limits ensure that this potential power is always focused and intense, never blousy or fat.

Nearly all the great spots for Riesling are in Niederösterreich, the most north-eastern of the nine states of Austria, where the Alps peter out into the great Pannonian Plain of Central Europe. This is the slice of land along the Danube that includes the wine regions of Wachau, Kremstal, Kamptal, and the vast Weinviertel. The Wachau certainly offers up Rieslings of remarkable quality, the Kamptal is considered by some to be Austria’s Burgundy, with its greatest grand cru vineyard that of Heiligenstein (if we must use the terminology of cru in vineyards for the location is only potential energy, the kinetic energy is given by the method of farming).

The terraced slopes of the Heiligenstein dominate Kamptal’s eastern landscape. This place was originally documented in 1280 as Hellenstein, or “Hell’s Rock”—most likely in reference to the hot temperatures of summer days and possibly to the steepness of the slopes – reminiscent of the Mont Damnés in Chavignol. Long farmed by monks (whose chapel still marks the hillside), the name was changed by the resident clergy to Heiligenstein, or “Holy Rock,” around 1500 for obvious political reasons. Here, the warm winds from across the eastern plain are tempered by cool evening breezes from the Waldviertel forests and the Manhartsberg mountains to the north, prolonging the growing season and guaranteeing physiological maturity. The terraced vineyards of this 30 degree slope face south toward the plain where the Kamp River joins the Danube. Although rain is plentiful the growing season is generally dry, which allows organic and biodynamic farming—flags flown by many a local grower – although it was noticeable there are irrigation systems everywhere.

The soil, dating back 270 million years to the end of the Palaeozoic era, is worthy of study on its own. Before the Alps were formed, Sahara winds blew desert sand onto the original banks of the Danube. As the river, which was more like a sea at the time, receded south, gravel was deposited; that gravel now lies deep beneath a complex mixture of weathered crystalline slate, maritime sediment, volcanic rock, and the desert sand. Heiligenstein is more of a sandstone conglomerate than primary rock (as is found in the Wachau), jutting up to about 350 metres feet in elevation and above the adjacent hills, to catch the full effect of the sun’s rays. The pitch is too steep for loess to have accumulated—though that soil type is found at the base and is the home for some spectacular Grüner.

Heiligenstein’s mix of ancient soil and rock is exactly the kind of fuel that feeds Riesling’s hunger for minerality. Given its geological structure, the wines are always very mineral-driven and well structured. Others note that the wines are dense and yet extremely fine, with a kind of showy nobility; all agree on their cellar-worthiness. Riesling ripens later than Grüner; it is tempting to go for a powerhouse style, but all the growers we visited were seeking a certain tension in their wines.

The Jurtschitsch plots on this fabled hill are inspiring places to walk. They have created small heathland zones to attract insects and creatures and restored the terraces using local stone. From the healthy soil beneath your feet, the cheerful birdsong to the vivid light bouncing off the rocks off the terraces there is a brightness and palpable energy in their vineyards.

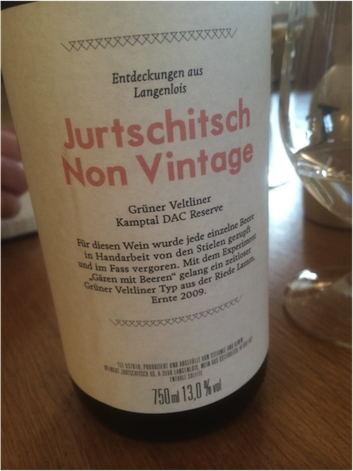

Back to the tasting room to sample their special project called Entdeckungen. We tried the Amour Fou (Grüner), Pot des Fleurs 2011 (Grüner also) and Quelle (Riesling). Wildly aromatic and expressive, unfiltered and unsulphured, the wines possessed a raw juice quality. One was instantly transported to those vineyards, vibrating with life. Alwin wants his wines to vibrate in the same way. The specific terroir is one thing – Alwin, Martin Arndorfer and Matthias Warnung see the vineyard and the soils as the beginning of the process, the evolution of the wine’s identity. All the minerality from carefully nurtured soils naturally communicates itself and has to be allowed to communicate itself, but the wine’s complexity is filtered through other natural processes and winemaking decisions, shaped, for example, by the interaction of the ambient yeasts (and the subsequent ageing period on the lees) and also by the very container in which the juice ferments and matures. Alwin and Stephanie use huge foudres, smaller barrels, stainless steel barrels, small tanks, demi-johns and there – in the cellar – raised on a plinth was a gorgeous Flowforms ceramic egg (see photo below). The extraction of flavour from the wine is not about forcing the issue but moving in different formats, thereby discovering different “taste-shapes”.

Liberated thinkers question every aspect of vine growing and winemaking. They are no longer slaves to convention (that convention is, at most, two generations old). Many vignerons are cultural archivists, resurrecting grapes, wine styles and traditions that were abandoned in the post-war dash towards chemical farming and flavour-stripping winemaking techniques that resulted in commercial homogeneity. They are not harking way back for the sake of it, but are conscious that history has a wider sweep than 50 or 60 years, and that to understand the future firstly you need to understand the past.

The journey of single wine comprises many steps and interesting detours. Matthias Warnung worked with Craig Hawkins who worked with Dirk Niepoort. His sensibility is similar, but his approach is necessarily different. Kamptal is not Swartland, after all. However, his mind set and approach is at variance with other local growers. With Alwin and Stefanie you have a further element in the equation. They have taken over a winery with a famous name, one that trades on its traditional image. Although it would be tempting for them to renounce everything in the immediate past you have to build on what is there already. And so they have created their own separate project to pursue their wine dreams and fantasies and will gently guide the mainstream wines into a more natural idiom. The Arndorfers are also custodians of the family business – the transformations in winemaking must be subtle rather than alienating. They have created their own label, which they have further subdivided into four further bands (rather than brands), according to the style, the feeling behind the wine, and the degree of experimentation involved.

Standing on the Heiligenstein, looking around, one can sense the past, the present and the future. The sense of place, elevated above the valley, with its amazing historical background, is powerful. Some of the walls that support the terraces are crumbling, some of the vineyards have been engineered to make tractor work easy. Some of the most stunning vineyards with the oldest vines are being abandoned – or maltreated. With love and nurturing this glorious patchwork of vineyards might be resurrected integrated into a fully biodiverse environment. This requires patience, a labour-intensive approach and an understanding of the vineyard as an organism. These qualities (embodied in the work of Alwin and Stefanie as well as Martin and Matthias) are intrinsic to the ethos of natural winemaking, which is not about neglect and abandonment, but rather a serious investment of time and effort in creating the physiological preconditions to get the best possible material from the vineyards. Thereafter, you can channel the sacred juice with all those inherent complex mineral components towards the complete wine. Or rather the wine that feels and tastes complete in itself. Terroir is about the history and the natural environment; by helping to revive that terroir in the vineyard, the vigneron may rediscover its underlying signature in his or her wines.

The talk in Austria is not so much polarised natural and conventional, but centres on tradition. The modernists have taken the word and moved it on. They look back because without the history of the vineyards and the sense of place there is nothing to draw on. However, they are seeking to interpret their patrimony in a more dynamic fashion – working without chemicals in the vineyards, reviving the health of the vines, using natural yeasts ferments at ambient temperature and slowly raising the wines until they find their own balance.