As well as places for retreat, prayer and ascetic contemplation, monasteries have historically been associated with, amongst other disciplines and crafts, reading, writing, scientific research, farming and winemaking.

Telavi Monastery

GELATI – the monastery with no ice cream

Gelati, aka The Monastery of the Virgin, was founded by the King of Georgia David the Builder (1089-1125) in 1106. The Gelati Monastery for a long time was one of the main cultural and intellectual centres in Georgia with an academy that employed some of the most celebrated Georgian scientists, theologians and philosophers, many of whom had previously been active at various orthodox monasteries abroad or at the Mangan Academy in Constantinople. Among the scientists were such celebrated scholars as Ioane Petritsi and Arsen Ikaltoeli. Due to the extensive work carried out by the Gelati Academy, It was known as the time as “a new Hellas” and “a second Athos”. The Gelati Monastery has preserved a great number of murals and manuscripts dating back to the 12th-17th centuries. In Gelati is buried one of the greatest Georgian kings, David the Builder (Davit Agmashenebeli in Georgian).

Popularly considered to be the greatest and most successful Georgian ruler in history, David succeeded in driving the Seljuk Turks out of the country, winning the major Battle of Didgori in 1121. His reforms of the army and administration enabled him to reunite the country and bring most of the lands of the Caucasus’ under Georgia’s control. A friend of the church and a notable promoter of Christian culture, he was canonized by the Georgian Orthodox Church

Humane treatment of the Muslim population, as well as the representatives of other religions and cultures, set a standard for tolerance in his multiethnic kingdom. It was a hallmark not only for his enlightened reign, but for all of subsequent Georgian history and culture.

David the Builder died on 24 January 1125, and upon his death, King David was, as he had ordered, buried under the stone inside the main gatehouse of the Gelati Monastery so that anyone coming to his beloved Gelati Academy stepped on his tomb first, a humble gesture for a great man.

With its beautiful frescoes, mosaics, and excavation of ancient qvevri cellar (which looked like fossilised qvevri catacombs!) it is no wonder that this is a UNESCO World Heritage site. The setting is striking with the monastery complex perched high on a bluff with spectacular views towards the distant range of mountains. The monastery is still very active as a place of worship as well as a magnet for tourism.

IKALTO – The historic groves of wine academe

Ikalto is a village about 10 km west of the town Telavi in the Kakheti region of Eastern Georgia, known for its monastery complex and the Ikalto Academy. The Ikalto monastery was founded by Saint Zenon in the late 6th century, one of the 13 Assyrian Fathers, a group of monastic missionaries who arrived from Mesopotamia to Georgia to strengthen Christianity in the country. They are credited by the Georgian church historians with the foundation of several monasteries and hermitages and initiation of the ascetic movement in Georgia. One of most significant cultural-scholastic centres of Georgia, the academy itself was founded at the monastery during David the Builder’s reign by Arsen Ikaltoeli (Ikaltoeli meaning from Ikalto) in the early 12th century and trained its students in theology, rhetoric, astronomy, philosophy, geography, geometry, chanting, as well as more practical skills such as pottery making, metallurgy, viticulture and wine making and pharmacology. According to a legend the famous 12th century Georgian poet Shota Rustaveli (The Knight in The Panther’s Skin) studied there.

One could easily imagine the monks studying here; it is a tranquil place, very cool, green and sylvan, throstling with birdsong. On the day we visited the air was damp, mist clung with to trees and slopes. Which made me feel very much at home.

ALAVERDI – Mona-vinfication

Qvevri catacomb

Qvevri catacomb

The Alaverdi Cathedral is located on the Alazani Valley, near the village Alaverdi (Akhmeta region), 20 km from Telavi. Joseph, one of the thirteen Assyrian fathers, founded a monastery in the middle of the 6th century. He is also buried here.

Alaverdi was the main church and place of worship in Kakheti in the 8th-10th centuries. The present day cathedral which replaced the older smaller church of St George was built in the first quarter of the 11th century, when the King of Heret-Kakheti Kvirike III (1009-1037). Later the Bishop of Alaverdi is mentioned in the sources at the time of David the Builder. In the period of political disintegration of Georgia (the 15-th – 18-th centuries) the Bishop of Alaverdi – Amba of Alaverdi, who was granted the honour of Metropolitan, was in fact the head of the church in the Kingdom of Kakheti. The title “Amba” was given to the Bishops of Alaverdi, because they were heads of a monastery as well. The existing documents show the special position occupied by successive Bishops of Alaverdi and the respect with which Kings of Kakheti treated them.

Despite several restorations, the Church retained its original forms. It is a strict, harmoniously built monument of grand spaces and integral composition.

Alaverdi, as the principal church of Kakheti, was the burial-place of the King of Kakheti. The Alaverdi Cathedral also became a significant cultural centre, home to scribes and bookbinders.

“Kakhetian” vinification method in a large nutshell

So we have seen the qvevris everywhere; what distinguishes the vinification and gives the Kahketian wines their strong identity?

After pressing, the must is poured in the qvevri and with it the so-called chacha, that is, the marc (skins, pips, stalks). As a rule, the chacha is added in its entirety, but sometimes the winegrower decide to jettison a portion of it (for example the greener or more immature parts such as the unripe stems). It all depends though upon the quality of the grapes and the character of the wine that they intend to produce.

During the alcoholic fermentation, which normally lasts about 10 days, the qvevri remains uncovered in order to immerse or plunge the “cap” of marc that floats on top of the wine, allowing the release of polyphenols and other compounds contained in those skins, pips, and stalks. By burying the clay vessel, the temperature of fermentation is maintained at a relatively equable 20 ° C, without any other special interventions.

At the end of the fermentation, the solids precipitate to the bottom of the vessel, making it possible to fill the qvevri through the aperture, and covering loosely with a lid, in order to allow the evaporation of the excess carbon dioxide during the malolactic fermentation. Only after the yeasts are exhausted (usually around mid-December) is the qvevri fully sealed. This is done with clay or wax and the qvevri is buried under a layer of soil or sand to ensure a better thermal insulation. For another three or four months, the wine matures in contact with the chacha and the lees, a process that takes place at a relatively constant cool temperature (between 12 and 15°C), made possible because the qvevri is buried underground. And the wine continues to be enriched with the substances deriving mainly from the skins, stems and the lees.

Having said that, the pips, which are the first to settle at the bottom after fermentation, thanks to the fusiform shape of the amphora have only limited contact with the wine, and this prevents the excessive release of the bitter tannins.

Crazy qvevri golf course in Ikalto

In March or April, the wine is removed from the solids and transferred into a fresh qvevri. Here, a second sediment is deposited at the bottom, and in about two months (usually between May and June) the wine is poured back into another clean qvevri, but this time it is fully clarified. It is customary to allow the wine to mature in qvevri for an additional 2 to 3 years, but it can also age for over 20 years. During maturation and in spite of the hermetic closure, a slow oxidation of the wine occurs through the porous walls of the clay qvevri, but also a limited evaporation. About every fifteen days the level is checked and if necessary topped up, so that the vessel is always full to the brim.

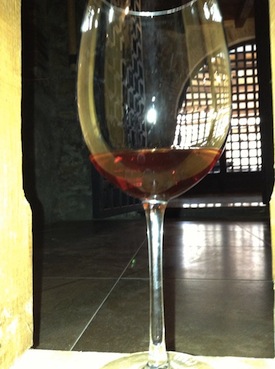

The wines produced using the traditional Kakhetian method are a style to themselves. The first intriguing thing one notes is the colour: dark, almost orange, between tea and amber, sometimes with a pinkish tinge. However, the characteristic that really sets them apart is the high content of polyphenolic compounds, extremely rare in other white wines, which often exceeds 2,000 mg/l. This content is more typical of red wines, but in the European white wines the polyphenols rarely reach 300 mg/l.

Research shows that the source of polyphenols is mainly found in the seeds (around 47%) and stems (42%) and only a small part in the skins (about 11%). It seems that this absolutely unique method of long maceration of white wines with stems has a crucial influence on the character of the traditional Kakheti wines. The stalks are the source of the valuable flavonoids, and enrich the wine with several aromatic compounds (complex esters, aldehydes, terpenes, aromatic alcohol etc.).

The high content of polyphenolic compounds makes the traditional Kakheti wines relatively insensitive to oxidation and unfavourable changes in microbiological conditions (mainly due to the antiseptic qualities of the flavonoids), and this in turn allows the winemaker to limit the sulphuring of the wine to a minimum.

See no evil, hear no evil, taste no evil

See no evil, hear no evil, taste no evil

Back to the present day…

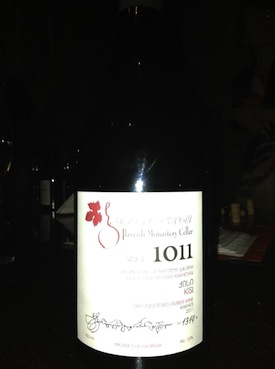

We ate a beautiful meal at refectory tables in a large hall, toured the Monastery’s wine museum, inspected the qvevris and enjoyed a small tasting with the twinkly-eyed Father Gerasim. The grapes for the wines are donated by members of the Alaverdi congregation – needless to say the vines are farmed organically and the wines made naturally.

We tasted a superb apricot-hued Rkatsiteli, a precisely engineered wine with classic nose of tea, apple and green plum compote, wild herbs, jasmine and ginger; a tender pink-hued strawberry-fruited Rose Rkatsiteli which was lovely and, finally, one of the best Saperavis I have tried, as black as a friar’s robes, thickly laden with cherry, currant and berries, wonderfully sapid and tasty, with relaxed astringency.

The wines seem to glow in that dark cellar as if it lit from within.

That wine seemed, strangely, to gather and amplify the remaining light. I asked the bishop (a former architect) what words he might use to describe it. “Golden wine,” he said, after a pause. “Gold is a thing of great value. When the painters were choosing colours, gold would give the most depth of impression. The wine has spring aromas, but at the same time those of golden autumn, because it has passed through those periods. You can even feel a bit of winter freeze in it, a coolness experience. If gold could have an aroma and a flavour, this would be it.” And then his iPhone rung. —The one and only Andrew Jefford

A qvevri groupie from Croatia!

A qvevri groupie from Croatia!

BODBE MONASTERY – Nino & Gvino

Bodbe Convent, home to the relics of St Nino, is situated in eastern Georgia (Kakheti), two kilometres south of the delightfully small town of Sighnaghi. The convent has a terrific view of the Alazani Valley and the snow-capped mountains of Caucasus. Except when it is obscured by cloud or heat haze.

Nino was associated with The Grapevine Cross also known as the Georgian cross and which is a major symbol of the Georgian Orthodox Church, dating from the 4th century AD, when Christianity became an official religion in the kingdom of Iberia (Kartli).

Saint Nino is traditionally depicted holding a grapevine cross. It is recognisable by its horizontal arms drooping a little. Traditional accounts credit Nino, a Cappadocian woman who preached Christianity in Iberia early in the 4th century, with this unusual shape of the Georgian cross. The legend has it that she received the grapevine cross from the Virgin Mary (or, alternatively, she forged it herself on the way to Mtskheta) and secured it by entwining with her own hair and came with this cross on her mission to Georgia. The familiar representation of that cross, with its peculiar drooping arms, did not appear until the early modern era, however.

According to traditional accounts, the cross of St Nino was kept at the cathedral in Mtskheta for centuries. During the Persian invasions, it was taken to Armenia and eventually to Moscow. Tsar Alexander I returned it to Georgia at the beginning of the 19th century after Georgia’s incorporation within the Russian Empire. This cross, a symbol of the Georgian Orthodox Christianity, is now preserved in the Sioni Cathedral in Tbilisi, Georgia.

The monastery now functions as a nunnery and is one of the major pilgrimage sites in Georgia. The grapevine symbol remains a powerful reminder of Georgia’s long association with wine-growing.

A busy day in Alaverdi

A busy day in Alaverdi

Well lit qvevri orbited by drinking bowls

Well lit qvevri orbited by drinking bowls

The Final Supra and Farewell to Georgia

A few final thoughts.

30 odd (and not so odd) folk from many different countries came to the Qvevri Wine Symposium in Georgia. Some were writers and photographers, some were winemakers who used clay pots in their vinification, and others were grizzled wine trade pros with a natural swerve to their step. The trip was organised to a t, balancing the needs of education, culture-vulturing as well as copious spiritual – and spirituous – refreshment. One can say without doubt that coming into contact with another culture teaches you about your own.

I have drunk new (new-old?) wine with refreshed eyes, by which I mean I understand better the context and the means by which the wines come about. Whilst I am wary of romantic generalisations I can see that wine in Georgia is a socially cohesive force, inspiring a country’s feeling of collective self-worth.

Also refreshing (for me) on this trip was the absence of snobbery and the notion that value of wine is something that can only be determined by a cabal of vested interests. Wine is celebrated here as part of life rather than deconstructed endlessly. There is a sense in Georgia that having entrenched cultural roots means that you value what you have more, even if what if what you have is very meagre. When the wine culture is so alive it suggests that tradition and modernity are opposing concepts.

In the UK we flatter ourselves that we have a sophisticated, discriminating wine culture. I’m not so certain. Wine is perceived as a commodity, prized as such, and so is perpetually commercialised. The wine trade en masse is forever trying to identify or anticipate the latest trend, never sure whether to lead consumers or second-guess their taste. Magazines are obsessed with brands from the bog-standard to the luxury; wine competitions parcel out points, trophies and other baubles to give critical legitimacy to the industry. Wine is often a controversial subject at the margins, but usually those controversies are shallow and provocative. The talk of wine is the talk about wine industry, a self-perpetuating media-garchy – never has so much been written about so little by so many.

You notice this intellectual and emotional disjunction particularly during a Georgian feast where wine seemingly serves a sacramental purpose. The presence of the traditional utensils, the reverence for the past and the relish for ritual is the manifestation of this. If you listen to the toasts and talk to the growers you will see how wine, so to speak, symbolically seems to permeate every subject, every idea in Georgian discourse. The vine, the qvevri and wine itself are powerful signifiers used to convey and link ideas about mankind, journey, hospitality, friendship, heritage and homeland. Finally, wine is a striking metaphor for different kinds of love and enlightenment, as it has been throughout the centuries (consider ancient poems such as The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam and The Book of the Winebringer).

The grapevine cross

In Georgia I never viewed wine as separate to the food, or apart from the people who made it or those with whom I shared it. Yes, in Georgia, wine is a catalyst, a great unifier. Georgian hospitality is a humbling experience – it is a gift, one that stays with you a long time. It is easy to forget that wine goes much much deeper than the bottom of a glass.

![1045038_509637892424634_587550664_n[1]](http://blog.lescaves.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/1045038_509637892424634_587550664_n1.jpg)

Ladles and jellyspoons

There’s nothing Nietszche couldn’t teach you about the raising of the wrist

The author’s effete attempt to drain the amber dregs.

Pingback: the 2 d Qvevri Wine Symposium in Georgia – Four Monasteries and no funerals: Georgian Adventures | domaine Georgia

Pingback: The Second International Qvevri Wine Symposium | Flow Forms

Hi guys. The “qvevri groupie” is actually from Slovenia, not Croatia. Enjoy!

Primoz Stajer