2) Don’t get hung up on semantics. “Natural” is a reasonable enough adjective to employ for a style of wine-making. There are some growers at the margin who may try a zero intervention cuvée; most attempt to limit chemical interventions to an absolute minimum and operate according to the dictates of the vintage. The more conventional winemaker will make wine according to a specific formula with a menu of predetermined interventions throughout the process. I think natural describes the spirit in which growers work rather than something too precise – and it is a holistic approach guiding the wine from vine to glass.

3) If you’ve had a bad example of a so-called natural wine, get over it. There will be plenty of bad examples. There are countless examples of terrible conventional wines that you would pour down the sink with equal alacrity. Don’t conflate the two entirely separate issues – one is about good and bad winemaking and what is about the very nature of what is faulty. These arguments are not the exclusive parole of natural wines.

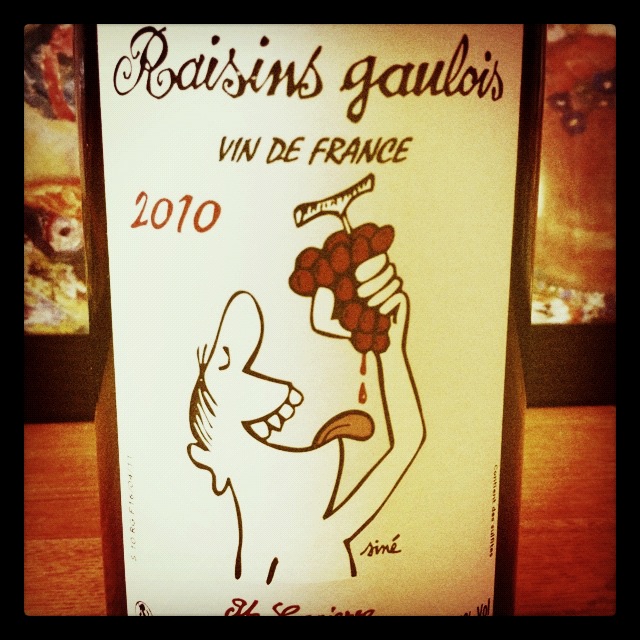

4) Conventional wine gave us sulphurous Beaujolais Nouveau and thermovinification. Natural wine gave us Marcel Lapierre, Jean Foillard, Guy Breton, Jean-Paul Thevenet, and, since then, several dozen other growers making world class Gamay.

5) The godfather of natural wine was Jules Chauvet. He was a winemaker, but also formerly a research chemist, micro-biologist and widely considered one of France’s greatest tasters. A swivel-eyed fanatic? No-one really thinks that.

6) Try to avoid repeating the chestnut that natural wines are more expensive. Than what? If anything the winemaking process tends to be cheaper because it is bound to cost less when you use no chemicals in the winery. A contributing cost factor is that natural wine is not made on an industrial scale and that it comes from organic or biodynamically farmed grapes which is a more labour intensive process. Great grapes cost more money because they involve quality control of the highest order. In any case though this notion that the wines cost more is a fallacy. Strip away the marketing budgets from brands and the differential is slight. Nowhere is this more clearly illustrated than in Champagne.

7) There are 50-odd allowable additions to wine to make it more stable and suitable for markets. Most consumers don’t know this and most wine writers don’t question whether this is desirable. Do we actually know what goes into the wine? Would we be less likely to buy a wine if there was a long list of chemical additives on the label? Winemakers who criticise natural vignerons need to look closer to home and state what degree of chemical intervention is acceptable and what is not.

8.) There are over 400 so-called natural wine growers making wine in a wide variety of styles; there are hundreds of wine shops, wine bars and restaurants dedicated to these wines and there are hundreds and thousands of people drinking and enjoying these wines every day. Please don’t patronise by telling them that they don’t know what they are drinking.

9) Wine is treated as something entirely separate to food because it undergoes transformations. Cheese and bread also (amongst others) undergo transformations. Why are the interventions in wine sacrosanct? Why, because it is made with the help of man, does it have to be man-made? Do unpasteurised cheeses, natural ciders, real ales get the same critics hot under the collar because of their naturalness? Of course not.

10) Stability is held aloft as a virtue. How dull would the world be if we were all alike, if artists and musicians created their works for a middlebrow audience, if every bottle of wine was safe and neutral because each winemaker worked to the same oenological formula. It is natural to be creative and it is creative to be natural.

Years ago (like the 1980s) I worked out that I preferred small producers who hand-picked their grapes and who were artisan or boutique. At the time I didn’t have a name for it and perhaps, even today, we might call them authentic or artisan, or natural and so forth. The word for me does not matter; the wine does. Why I like CdP is that it has a bunch of wines that make sense to me. If you want industrial wines, then go and buy them in a supermarket.

Late last year I was on a flight back from Tokyo to London on an airline other than Air NZ (which has reasonable wine for a long haul flight) and what I got in my plastic receptacle was a bunch of chemicals from the bottom of a vat that was highly toxic. I marched to the back of the plane and told the staff not to serve the wine to anyone else and explained why; I also complained to the airline and received no response. The problem with industrial wines is that they are ‘adjusted’ for regularity and killed on the spot.

I teach, and one of the things I have to teach my students is that there are no correct answers, and their individuality matters more than pro forma correctness. It is the same with wine; take a risk, drink something different, try things from the list. How many people, for instance, have tried the Bressan Schioppetino? It is a really good wine; half way between a syrah and a pinot with a white pepper nose; black almost to the rim, very clean and pure, very fine and precise rather than heavy; really lovely wine.

Buy a case of a dozen different wines; try them and learn: it is that simple.

Thank you for sharing Mark, we wholeheartedly agree!

Look, I haven’t even read this article yet, just glanced at it. And I see that photo, the one near the top with all the people eating. What a lot of shady looking characters they are.

Shady indeed. All trying to pull the wool over our eyes, clearly