Continued from Chapter Two, Part One. Read Chapter One Parts One, Two and Three here.

Digression Concerning the Art & Nature of wine transformation

Science commits suicide when it adopts a creed.

—Thomas Huxley

The subject of wine (not just the wine itself) is sometimes in danger of becoming an intellectual dead-end due to the rigorous-to-the-point-of-being-hamstrung appliance of science in almost every facet of our understanding and appreciation of wine. Not just applying it to the manufacture of wine where nature must be driven out with a chemical pitchfork nor to the juice which has been cleansed of natural yeasts, but to our opinions that must be perfectly formed, proved on the very anvil of logic. All is for the best in the best of all fearlessly symmetrical, bravest-of-brave-scientific-worlds.

Reductive wine science

In reality wine has become a quasi-discipline (for want of a better word) foundering on the rocks of faux-science. Journals abound with articles written by scientists and science groupies whose sole objective seems to be to atomise wines and strip them from their natural and human context. Facts are not science any more than the dictionary is literature. This leads instead to an interesting polarisation between those people who will always have an emotional response to wine, who feel wine on the pulses, for whom the smell and the taste of wine conjures shapes, colours and memories and elicits personal pleasure, versus those with a propensity for uber-dissection, who value functional rightness and wrongness -to the point of self-righteousness, who believe that the language of wine should be forever couched in the finite, numerical language of science rather than that of the over-vivid imagination.

Take the subject of faults and flaws. Many are happy to subscribe to any research that is done under a microscope in a laboratory as if by switching off the emotional response you will inevitably arrive at an objective truth about a wine. You can also study a painting under a microscope, but that is not the whole picture any more than an x-ray of someone can inform the observer what that person is truly like on the inside. Meanwhile, ascribing a name to a wine characteristic – be it VA, brett, reduction, oxidation –has become the default aesthetic of the wine trade, a means of filtering out the unusual or individual. Never mind that many so-called faults are relative flaws and may actually enhance the wine. Wine – to certain professionals – is the sum total of its obvious faults (or lack of them) and the self-appointed cognoscenti have arrogated to themselves the unofficial title of faultfinder generals. And taste arbiters. Wine, to use the ghastly cliché, must be fit for purpose. According to many opinion-formers wines are better when they are made in a specific style. As with the models there is a perfect (and therefore a perfectible) shape (albeit that these models are Rubenesque to say the least). So much so that you can ascribe marks, award medals and effectively add value to the product. As soon as one calls into question the validity of these value judgements and dispute the very nature of faults and flaws, then the quixotic baby beats the nurse and quite athwart goes all decorum. Eternal verities and hierarchical systems go out the window – undermining the whole system of classification. But farming, winemaking, opinion itself has never been static. What our ancestors enjoyed drinking would probably be considered faulty today, and what the critics laud now, might well be regarded as undrinkable in 50 years’ time.

This leads instead to polarisation between those people who will always have an emotional response to wine, who feel wine on the pulses, for whom the smell and the taste of wine conjures shapes, colours and memories and elicits personal pleasure, versus those with a propensity for uber-dissection, who value functional rightness and wrongness, who believe that the language of wine should be forever couched in the finite, numerical language of science rather than that of the over-vivid imagination.

“Science, like life, feeds on its own decay. New facts burst old rules; then newly divined conceptions bind old and new together into a reconciling law.” ~ Will James, The Will to Believe and Other Essays in Popular Philosophy, 1910

Yes, our interpretation of faults differs; for some the mere presence of aldehydes, brett, VA and reduction is sufficient to deem the wine in question faulty, while for others it is a matter of degree. I believe that certain wines are so diminished and adulterated by the flavours of chemicals or particular additives that they are also faulty – one might characterise natural faults as sins of omissions as opposed to clumsy oenological faults which are sins of commission. If one substitutes flaws for faults we may then understand that the objective of wine is not to be perfect (faultily faultless, icily regular, splendidly null to quote Tennyson) but to be individual. And vive la difference is surely a desirable mantra. Philosophy? Schmilosophy. We are all philosophers in our pots. Diversity thrives on opposition, the dynamic-creative energy of conflict. The natural wine movement didn’t spring fully-formed out of the head of some vainglorious style guru looking for a fad to peddle but was the result of growers becoming increasingly disenchanted with the same-old, same-old chemical-smelling, chemical-selling wines. Marcel Lapierre used to reminisce that he couldn’t bring himself to drink his own wine. When the growers can’t drink their own products that is a problem we should all be prepared to address.

Let us examine those wines that inhabit the reckless wilder shores and that tend to alienate those who believe that cleanliness is next to godliness. These wilder wines can be alive, joyously, bacterially alive, mutating, unveiling, clamming up, moving, growing and decaying. They do not have a steady-state existence, nor are their transformations always obvious, inevitable or explicable. The vigneron will help to shape and to set the wine on its transformational journey, be it a long journey or a short one. The other side of the story is the wine denatured by chemical intervention in the vineyard and winery, homogenised and pasteurised by process. This wine was never alive, any more than the soils of the vineyard where it originated and have been subjected to herbicides, pesticides, fungicides and chemical nutrients, were alive. This wine can never be transformed because it has been given all its artificial DNA by the winemaker. Then there are the wines in-between, which retain the life-message of the vineyard, where oenological intervention has not entirely thrown out the baby with the bathwater.

Something from something

Here’s the rub. Nothing can come of nothing. The Roman poet and philosopher Lucretius expressed this principle in his first book of De Rerum Natura Principium:

Principium cuius hinc nobis exordia sumet,

nullam rem e nihilo gigni divinitus umquam

Transformation is integral to wine. In certain vineyards where the soils are hot and teeming, the humus sweet and friable, where grass, plants, herbs and flowers thrive, there is natural exchange between the vine and its environment. This is the life in the wine.

The natural wine movement didn’t spring fully-formed out of the head of some vainglorious style guru looking for a fad to peddle but was the result of growers becoming increasingly disenchanted with the same-old, same-old chemical-smelling, chemical-selling wines.

Life amongst the vines translated into life in the wine, recalls Ovid’s observation, when he writes in Metamorphoses: Omnia mutantur, nihil interit (all things are but altered, nothing dies).

No species remains constant: that great renovator of matter

Nature, endlessly fashions new forms from old: there’s nothing

in the whole universe that perishes, believe me; rather

it renews and varies its substance. What we describe as birth

is no more than incipient change from a prior state, while dying

is merely to quit it. Though the parts may be transported

hither and thither, the sum of all matter is constant.

Why is this so important? Stefano Bellotti of Cascina degli Ulivi describes the very roots of transformation in wine in Jonathan Nossiter’s Natural Resistance:

A single plant of wheat – a single plant – cultivated naturally, penetrates up to 12 metres with its roots. And produces up to 5 kilometres of ancillary roots. A plant of wheat as it is cultivated today, agro-chemically, penetrates into the soil only 5-10 centimetres and produces only a few 100 metres of subroots. So, that’s a reduction 100 times of the root system.

What dialogue can a plant have with the mineral world, when its ability to penetrate with its roots is so compromised, thanks to mistaken agronomic methods that cause desertification? In the case of wheat, we have a plant that no longer nourishes us. It produces intolerances, allergies, the need for dietary supplements, etc.

Before, if you ate bread, it was bread. People could live nearly on bread alone. Because bread contained nearly everything man needs. We know that’s no longer true today.

When we talk about wine, we’re talking about a plant that should be able to penetrate deep into the soil. And it’s by definition a terrestrial plant. So, among all the fruits, grapes should be the richest in mineral salts. That’s why wine is wine. Because mineral salts are transformed into aromas during fermentation. So, everything from the mineral world – the latent flavours – are transformed by the magic of fermentation into actual flavours. If we take a plant that should work at a depth of 50-60 metres, but thanks to a senseless agronomic method, works at 60 cm… – because today vines work at a depth of 50-60 cm., depending on the soil – they’ll obviously lack everything that makes a grape a grape, or a Cortese a Cortese, etc. So, you have to reconstruct in the winery tastes which are more or less recreated and standardised.

Dialogue with the mineral world, complex root systems providing nourishment to the grape through the vine, latent flavours becoming actual flavours – natural wine is about realising all this potential. Transformation is not taking and changing for the sake of it – it naturally renews and varies its substance. The growers that work with the land, who, having used its resources, help to re-animate it, by allowing it to replenish itself, are simultaneously custodians, interpreters and gentle shapers. This is no way a kind of neglect, it is far easier to destroy than to rebuild, to exploit rather than work in harmony with. Eventually, when good practice is followed, the healthy labour in the natural vineyard (using the word labour in both its meanings) progresses through assured rhythms and cycles – the transformations are not brutal and short, rather the vineyard is a living record of the year and the wine that issues from its grapes bears the significant imprint of that vintage.

The winemaker captures – then liberates…

Some of our favourite wines have an aerian quality to them as if the vignerons have been channelling, translating and transforming, rather than constructing rigorous templates and working by objective analysis to create a common product.

Thinking inside the box

And now let use return to our laboratory-bred sheep. It is wonderful to understand the physical, chemical and micro-biological processes that describe molecular transformations that make wine what it is, but it seems that this self-same knowledge relentlessly drives the oenological desire for controlled outcomes. To achieve these outcomes, you must remove the natural elements from the equation and thus the wine becomes denatured through manifold interventions, its original identity stripped for reshaping, in short, a kind of vinous plastic surgery. “Nature hath given you one face and you make yourself another.”

Elena Pantaleoni of La Stoppa expounds on this subject, again in Nossiter’s film, Natural Resistance:

The first year they teach general chemistry. Then organic chemistry. What it’s made of. Then they teach you how to make wine. So, what is wine? They explained that wine is a series of things… that are obviously not natural. You take the grape and work it so that it becomes a product, basically, like Coca Cola.

Because errors are not admissible, they teach you. You can’t make an error. So natural wine, for them, is an error. You have to know exactly what you want. Then do it. And you need to be capable of achieving the predetermined product.

They teach you an industrial approach, the marketplace. They teach you how to make a saleable product.

They don’t teach you history. They don’t teach why you make wine. Or who did it before and how. No, they tell you: “today you plant.” And to get maximum yields, you need to do this, that etc. This is the right way to plant. If you have this kind of soil, you do this. That way you’re sure to have “X” production.

Various natural vignerons have encountered this strident scientific didacticism that preaches the one true winemaker’s path. Bertrand Celce of wineterroirs.com describes Rene-Jean Dard’s education at the hands of oenological Jesuits.

Rene-Jean Dard had already a long experience in winemaking as he had helped his father… His father made wine for the family consumption and a little bit for sale. The teaching in Beaune was for conventional, additives-loaded winemaking, and the only time they had a course about organic management, that was to mock it and warn about the risks. Actually, that’s in the school that Rene-Jean learned about SO2, his father having never used any in his winemaking. SO2 was one additive amongst many other that he was taught to use extensively in Beaune.

Natural vignerons celebrate terroir for what it is. The way they communicate with that terroir is what gives the wines their personality. Their activities are dedicated to converting nature to…nature. When we drink their wines, we are drinking a transformation that is not formulaic or circumscribed, but natural and imprecise.

Terroir rocks!

#liquidlimestone

…Mark these rounded slopes

With their surface fragrance of thyme and beneath

A secret system of caves and conduits

That spurt everywhere with a chuckle

Each filling a private pool for its fish and carving

Its own little ravine whose cliffs entertain

The butterfly and lizard…

In Praise of Limestone, WH Auden

Kimmeridgean

This is very Kimmeridgean.

Ah, you find that?

Oh, yes, typical Kimmeridgean.

That’s funny. I’m getting more of the Turonian.

Turonian, are you crazy? It is anything other than Turonian!

Well, I’m definitely getting the Turonian.

What’s wrong with your nose? Can’t you smell that we are right on the money with superior Jurassic?

Well, matey, that’s your opinion, I say that it is from the Cretaceous period, and that it is blindingly obvious.

The salty, iodine notes. It can’t be anything other than Kimmeridgean!

Pfff…

And…don’t you think it could be Senonian?

Senonian – you’re talking total and utter nonsense!

That’s the stupidest thing I’ve ever heard anyone say ever!

Mimi, Fifi & Glouglou, Michel Tolmer

A few years ago, I was in Portland (Oregon) surrounded by a group of wine enthusiasts who indubitably knew their Charmes from their Perrières, and their Senonian from their Turonian. I was invited to inspect someone’s treasure trove of fine wine, and duly selected – to her evident approval – a bottle Dauvissat Chablis 1er cru. A great vintage, and a legendary single vineyard wine from a legendary grower.

The wine from De Moor seemed to have a pulsing electricity, a brilliant energy, as if every living organism in the wine was flowing (racing almost) with the same purpose in the same fine line.

The wine was uncorked; the congregation murmured appreciatively at its unalloyed backwardness. Fifteen years on, and the fugitive chalky-limestone signature was encased in a liquid carapace, coiled forever in upon itself…

One has to cast aside the reputation for greatness and feel what the wine is doing in the glass. For me, this Chablis was barely unveiling an illusion of terroir. Instead it was monolithic, hardened by the high addition of sulphur to the wine. I mentally compared it to one Chablis Coteau de Rosette from Alice & Olivier De Moor. The wine from De Moor seemed to have a pulsing electricity, a brilliant energy, as if every living organism in the wine was flowing (racing almost) with the same purpose in the same fine line.

Their wine has energy, purity and natural balance in a light and delicate framework. Cool and understated like yer very best Chablis. As we know, wine connoisseur Sly Stallone, prefers Chablis because “it is the purest expression of the Chardonnay grape.” Who are we to disagree with the Rimbaud of wine criticism?

Tears of limestone joy…

We love wines that have nerves of steel, or as we sometimes call it, #attentiontotension. 1902 Plantation Aligoté by Alice & Olivier de Moor is one such paregoric potion. This wine is made from very old vines – vines that are unusual as they pre-date the ravages of phylloxera in the region. The vineyard is near the village of Saint-Bris-le-Vineux and covers barely half a hectare. The records show that the vineyard was planted in 1902 – hence the name – on rocky Kimmeridgian and a subsoil that alternates between mother and clay rock.

Kimmeridgian? Turonian, surely!

Feck off!

The De Moors have farmed their vines organically since 2005, a rarity in the area. Rigorous deep pruning, sensitive de-budding and careful canopy management with manual leaf thinning are all carried out to control the yields and ensure the best, most expressive grapes. Wild grasses are allowed to grow between the rows and they work the vines using a horse.

Winery work is straightforward with a wild yeast ferment in oak barrels, (malolactic occurs naturally) before the wine matures in old oak for eleven months. No fining or filtration and minimal use of sulphur – only a tiny amount added at bottling and none during vinification.

Fermented and aged in old oak the 1902 an Aligoté to age, extremely tight and high in stony acidity with citrus fruits and herbal aromas, very dense and long. This winespeak does not do justice to a wine which shimmers with authority – it has dense – or intense – transparency in the way that only wines with “perfect pitch” acidity can seem to glisten. Then the nose – glacier water buffing up a river stone, gorse flowers drenched with sea spray, all nostril-arching brilliance and then into the palate – linear, citric (juice plus pith), tears-of-chalk-stony, with tensile strength and just a smattering of lees spice. Liquid steel, this wine is an exhilarating skate across the palate. To coin a phrase, it takes you hither and Yonne. You can also drink it at 18.59.

There is something about limestone. Talk to Franz Weninger in Burgenland and you will notice that his enthusiasm for this soil type is infectious. For him Blaufrankisch-on-chalky-limestone soils acquires a fluidity and energy that balances the natural power of the grape variety in this particular part of Austria. Limestone, of course, comes in many forms and in many different soil mixes, allowing for incredible differentiation and variety in the wines. Jean-François Ganevat makes plot-particular Chardonnays, vinified according to their soil types, and aged in either small barrels or demi-muids. The differences are profound – a Chardonnay and a Savagnin from the same vineyard will taste more similar than two Chardonnays from different vineyards.

Thierry Germain’s white Saumurs skid effortlessly on their respective classy limestone chassis. His Insolite, made from 80-year-old Chenin vines, is as keen as a whippet with mustard on its nose, with refined mineral fruit to boot, its purity testament to biodynamic viticulture and the paring back of the winemaker’s interventionist role.

Above, and tongue-archingly beyond. Clos Romans is Chenin Blanc rooted in the walled clos of a priory that dates back to the 11th century. Conventually pure as the advert for a certain brand of mineral water used to say, annoyingly. The soil consists of a 30cm layer of sandy clay over Senonian-era limestone bedrock called Pierres de Champigny. It’s the same rock that was used to build the Château Champigny. Germain acquired this historic site in 2007 and has been steadily replanting at a density of 10,000 vines/hectare. He practices selection massale, mixing plants to ensure he does not get a mono-dimensional profile of this terroir. Volumes are tiny with handpicked grapes whole-bunch-pressed and then fermented for two months in a single 400-litre oval cask for nine months on lees.

The vine’s roots burrow down through the limestone, towards Parnay’s famous troglodyte dwellings below. This is dramatically tense, crystalline, mineral-bound and soaringly pure Chenin, with dazzling, earthy and stone fruit notes, fine, old vine structure and a lifted, saline finish. It is epic Chenin where the limestone seems to have wept tears of joy into the wine – all raging purity and longer than the collected works of Proust. Saumur’s lease hath all too long a date.

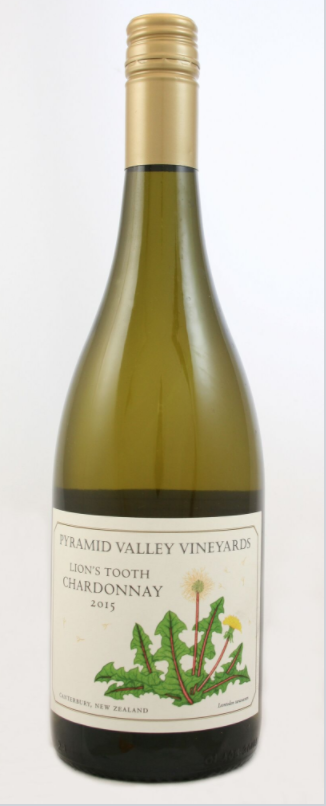

Pyramids-upon-lime

Our third illustration of lime-wine originates in Waikiri in Northern Canterbury in New Zealand. We’ve had a soft spot for this region’s limestone-active soils and the vines they support ever since we used to import the wines of Danny Schuster. Danny adored a penetratingly high acid Chardonnay that he made from limestone-rich soils. As he was wont to say (again and again) “I like my fish with lemon juice not sugar.”

The home vineyards of Pyramid Valley are not far away from Danny’s old lemon juice haunt. Mike and Claudia Weersing were perfectly attuned to the message of the vineyard. “Whatever means, methods, mentality we believe should produce a truer, more transparent and authentic wine, we invoke here. Our plant density is the highest in New Zealand, our yields austere, and the vineyard environment – embracing soils and plants and animals and insects and above all, people – is lavished with care.”

Mike continues: “Wine to us is a genie, genius loci; our task is to coax it from its stone bottle. Wine’s magical capacity for evoking site, we consider an obligation, as much as a gift. Every gesture we make, in the vineyard and winery, is a summons to the spirit of place. Biodynamics, hand-based viticulture, natural winemaking – these are all means we’ve adopted better to record and to transmit, with the greatest possible fidelity, this spirit’s song.”

To record and transmit, with the greatest possible fidelity – this is worth repeating. Wine can be this summons to “the spirit of place”. Or put another way, the terroir is the elemental spirit, the vineyard is the music, the wine is the interpretation and the vigneron is the conductor.

The two Pyramid Valley Chardonnays show how small terroir difference may be amplified and further articulated during the transformation from grape to wine. Field of Fire presents a glorious nose of baked peach, pastry, and yellow flowers – acacia and fennel blossom. Lush on entry, but quickly turns streamlined, from stony acidity and girdling phenolics: great volume and energy, condensing and accelerating on the palate.

Lion’s Tooth Chardonnay, on the other hand, has flavours of yellow peach, ground almonds, and lemon curd. With an intense kind of inwardness, the wine seems to fold in upon itself, condensing to an astonishing saline core. Enormous force and length, with alternating assertions of golden flavour – ripe pear, toast, flower honey, nuts – and chalk-hard structure.

As objective markers, tasting notes are notoriously unreliable, but it is commonly agreed that the difference between one Chardonnay and the other, is marked. Which says so much about the personality of the vineyards and the different types of minerality that the respective limestone soils confer.

#hotschist

There’s more to terroir than having vines planted in sexy soils.

Only the crumbliest… flakiest… schists.

Tell me where is terroir bred

Or in the heart or in the head?

How begot, how nourished?

–With apologies to Will Shakespeare

How indeed?

Bonny Doon loveable loon, Randall Graham gives his sage two cent’s worth:

“…we love and admire individuals in a way that we can never love classes of people or things. Beauty must relate to some sort of internal harmony; the harmony of a great terroir derives, I believe, from the exchange of information between the vine-plant and its milieu over generations. The plant and the soil have learned to speak each other’s language, and that is why a particularly great terroir wine seems to speak with so much elegance.”

Continues Grahm: “A great terroir is the one that will elevate a particular site above that of its neighbours. It will ripen its grapes more completely more years out of ten than its neighbours; its wines will tend to be more balanced more of the time than its unfortunate contiguous terroir. But most of all, it will have a calling card, a quality of expressiveness, of distinctiveness that will provoke a sense of recognition in the consumer, whether or not the consumer has ever tasted the wine before.”

Expressiveness, distinctiveness: words that should be more compelling to wine lovers than opulent, rich or powerful. Grahm is talking about wines that are unique, wherein you can taste a different order of qualities, precisely because they encapsulate the multifarious subtle differences of their locations. Grahm, like so many French growers, posits that the subtle secrets of the soil are best unlocked through biodynamic viticulture: “Biodynamics is perhaps the most straightforward path to the enhanced expression of terroir in one’s vineyard. Its express purpose is to wake up the vines to the energetic forces of the universe, but its true purpose is to wake up the biodynamicist himself or herself.”

Although he eschews the BD word, Didier Barral has 25-hectares of biodynamically-farmed vineyards in Faugères on acidic schist soils in which a little of everything grows. Everything starts from the soil which must be made as healthy as possible.

His photographic album of the vineyards might be entitled: My Favourite Bugs or A Diet of Worms – or even A Riot of Worms, for it reveals astonishing diversity of benevolent creepycrawlydom, indicative of a thriving, living soil.

Didier is clear that terroir concerns the whole living picture. “Nowadays, farmers feed the planet but destroy it at the same time. Sometimes they think they are doing the right thing by ploughing too often for example, which eventually damages the soil structure. We have to observe nature and to understand how micro-organisms operate. Then we see that tools and machinery can never replace the natural, gentle work of earthworms, insects and other creatures that travel through a maze of tunnels, creating porosity and aerating the soil, making it permeable and alive. There’s grass in our vineyards and amongst the grass, there are cows and horses: a whole living world that lives together, each dependent on the other and each being vital to the balance of the biotope.”

As someone once wrote: “We abuse land because we regard it as a commodity belonging to us. When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.”

This is an extraordinary micro-climate where the mountains on one side and the proximity of the garrigue which shelters fauna and flora create the preconditions for an excellent terroir. Didier is adamant that cow manure is the best, and not having delved too deeply into these matters, as it were, who are we to say otherwise? His photographic album of the vineyards (we’ve all seen it) might be entitled: My Favourite Bugs or A Diet of Worms – or even A Riot of Worms, for it reveals astonishing diversity of benevolent creepycrawlydom, indicative of a thriving, living soil. Natural solutions prevail: small birds make their nests in the clefts of the vines (these nests lined with the horse hair that has been shedded) and they prey on the mites and bugs that are the enemies of the vine.

A perfectionist in the vineyard, Didier also believes in natural vinification. Triage is vital for the quality of the grapes which makes or breaks the wine. He dislikes carbonic maceration as he believes that it explodes the fruit and leaves nothing behind it. The fermentation is done with wild yeasts, pigeage is by hand, long macerations are followed by ageing in wood, and the assemblage (all grape varieties are vinified separately) follows eighteen to twenty-four months later. No filtering or fining, these are natural products, lest we forget. As Paul Strang writes: “He scorns the modern bottling plant, deploring the use of filters and pumps which interfere with the natural qualities of the wine. All you need is a north wind and an old moon.”

The variegated shattered schists of the Languedoc-Roussillon produce some astonishingly fine wines.

To be continued in Part Three…