During the time of the year that people would like to re-invent themselves, some thoughts about what Donald Rumsfeld might call the certain uncertainties of the biz we are in. Uncertainty is healthy, chaos is energy and revolution pushes the boundaries.

Until recently people have tended to revere institutional reputations from the Royal Family, politicians and church leaders to scientists, writers and self-proclaimed experts in a particular field. Now, there are no sacred institutions, no area of expertise that cannot (and should not) be challenged. Reputation in the wine trade, for example, is often garnered by banking “wine experience” and clings to those rare avians who voluntarily taste many hundreds of wine in a day yet still preserve the “compos mentisness” to be able to express an authoritative opinion on everything. To be fair, the wine trade rewards those who do the hard yards, study their subject diligently and (more or less) accept received wisdom. Those who speak with authority, or who have acquired a forum to ventilate their opinions, on the other hand, have no monopoly on correct thinking or good taste for one’s wine education never ceases. As Frank Lloyd Wright said with justifiable cynicism: “An expert is a man who has stopped thinking – he knows!”

One rarely comes to wine with fully-fledged opinions, but, as one seeks expert status, one quickly learns to discover and absorb those orthodoxies espoused by respected commentators and writers in the trade. The more intelligent will see these opinions for what they are, as subjective opinions, rather than universal truths engraved in tablets of stone.

The opinion formers, rightly, would prefer to be characterised as cicerones, guiding people to acquire better taste and demystifying wine. To reach this status they must be viewed as experts, and to be considered an expert one should have clearly laid-out ideas of what is right and wrong and good and bad in wine. This crystallising of opinion about wine creates a kind of clarity, but may also serve to over-simplify the reality. Over time certainties become deeply entrenched prejudices whilst amour-propre replaces open-mindedness and the willingness to admit there are more things in heaven and earth etc. etc.

Knowledge is never simply about weighing up how much you know. It is the thirst for enquiry and the imaginative ability to explore issues in the round. And there’s more to it than that. Michel de Montaigne in his Essais noted that It is a dangerous and serious presumption and argues an absurd temerity, to condemn what we do not understand. As I have said previously it is easy for the critic to criticise the artisan who makes the wine. But there are reasons why things are done and turn out the way they do, and if we can liberate ourselves from our preconceptions we can give a more educated assessment as to the qualities of the wines and the winemakers.

Education is not to reform students or amuse them or to make them technicians. It is to unsettle their minds, widen their horizons, inflame their intellects, teach them to think straight, if possible. The same should apply to wine, but wine courses inculcate a narrow curriculum. Meanwhile, wine growers, particularly those who work naturally, believe, like Einstein, that education is what remains after one has forgotten everything one learned in school. Living and experiencing winemaking is valid; booksmarts only take you so far.

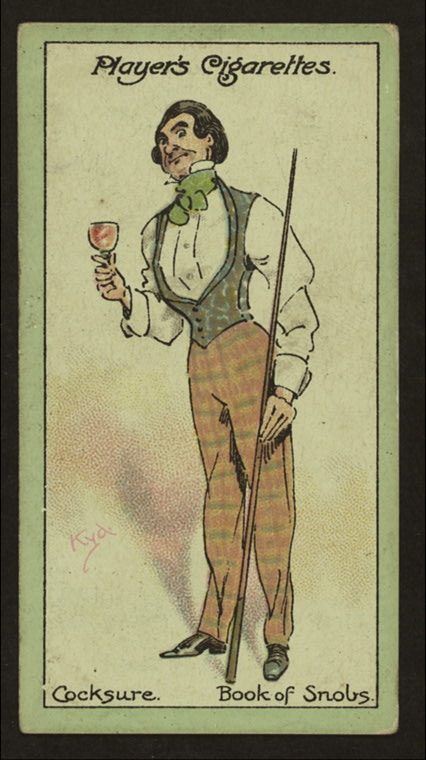

If we are honest the wine trade is still a magnet for vestigial snobbery. Man, proud man, drest in a little brief authority, most ignorant of what he is most assur’d, feels the need to assert his authority by derogating others and creating hierarchies of “good taste.”

The earlier stages of the dinner had worn off. The wine lists had been consulted, by some with the blank embarrassment of a schoolboy suddenly called upon to locate a Minor Prophet in the tangled hinterland of the Old Testament, by others with the severe scrutiny which suggests that they have visited most of the higher-priced wines in their own homes and probed their family weaknesses. The diners who chose their wine in the latter fashion always gave their orders in a penetrating voice, with a plentiful garnishing of stage directions. By insisting on having your bottle pointing to the north when the cork is drawn, and calling the waiter Max, you may induce the impression on your guests which hours of laboured boasting might be powerless to achieve. For this purpose, however, the guests must be chosen as carefully as the wine.

–The Chaplet – Saki (H.H. Munro)

So, what price is humility in the wine world? One doesn’t have to recant all one’s dearly-held conservative beliefs to become a tad more open-minded. As Ben Franklin observed: “For having lived long, I have experienced many instances of being obliged, by better information or fuller consideration, to change opinions, even on important subjects, which I once thought right but found to be otherwise.”

Being part of the mainstream is, of course, no guarantee that one is either correct or on the side of the angels. Bertrand Russell thought that the fact that although an opinion might be widely held “(it)… is no evidence whatever that it is not utterly absurd; indeed, in view of the silliness of the majority of mankind, a wide-spread belief is more likely to be foolish than sensible.”

When certain subjects are broached (particularly the whole natural wine thang), the quality of debate is degraded as a kind of quasi-rationalism takes hold, which then metamorphoses into vapid snobbery at best, and a didactic intolerance at worst. Those who engage intelligently with new sensations and new ideas help to move the debate forward; the true wine expert gives a fair hearing to those who hold opposing views, while the snob, informed or otherwise, retreats into the bunkered mentality where all is for the best or the worst in the best or worst possible worlds.

John Stuart Mill has the following philosophical take on this:

“The peculiar evil of silencing the expression of an opinion is that it is robbing the human race; posterity as well as the existing generation; those who dissent from the opinion, still more than those who hold it. If the opinion is right, they are deprived of the opportunity of exchanging error for truth: if wrong, they lose, what is almost as great a benefit, the clearer perception and livelier impression of truth, produced by its collision with error.”

Ultimately, good taste is intuitive, natural, and empathetic; snobbery is misanthropic, over-evaluative, affected. The love of anything can bring out the best or the worst in a human being. Wine, being the product of nature, should evoke happiness, laughter and good will towards other people, not drive us to distance ourselves from them because we think we understand and appreciate it more. The fact that your sense of smell is refined and that you may be able to insure your palate for a gazillion dollars is irrelevant: the literary examples of Hannibal Lecter, Des Esseintes, Jean-Baptiste Grenouille and Tarquin Winot illustrate that those who possess gilded taste buds can themselves be possessed by contempt for others. Taste – good taste – holds a mirror to your soul, and, as such, has a moral component.