Concerning a debate and a Q & A session with two producers for the trade organised by Sowine on behalf of Beaujolais and hosted with panache by Queena Wong.

The debate pivoted around the question: “Has Natural Wine Influenced Beaujolais Wine(s)? Speaking for the motion Anne McHale MW, who wrote her dissertation on Beaujolais eleven years ago, and me. On the other side of the argument, Natasha Hughes MW, currently researching and writing a book on the region, and Sean Evans, aka @geordiewineguide and Progression Wines.

The question was certainly open to interpretation and could easily have been flipped to read: Did Beaujolais influence Natural Wine. Yes! QED. Certain producers and their methods proved to be one of the sparks that ignited an interest in natural wine.

To return to the question. On the one side, the story of Beaujolais as a significant region could surely not be told properly without due reference (and deference) to the inestimable influence of natural wine producers. On the other side, one could say that while these producers might have a high profile, they are not the whole story of a region where commercial considerations are paramount if the wines are not to be priced beyond the means of the average consumer. In other words, natural wine producers are the elite, not the makers of everyday Beaujolais wines, a drop in the local Gamay ocean. One might further argue, as one panellist did, that natural wine itself is red herring, being a factitious term and no longer relevant to the practicalities of winemaking.

My thesis is the modern natural wine scene was born in Beaujolais and that its influence as a region producing world-class wines may be attributed to the considerable reputation of the numerous vignerons who work in a low-intervention way. Not only did the first natural Beaujolais producers influence other vignerons within their own region, the torch taken on by the succeeding generation, but according to the history of natural wine and its emergence from obscurity, one cannot underestimate the influence of growers such as Marcel Lapierre on top natural vignerons throughout the whole of France.

Without delving a little into Beaujolais history, and without reference to winemaking culture in the region and throughout wider France, one cannot appreciate the impact that these natural wine pioneers made. The history of wine in every region of the world inevitably concerns the stories of those who took the farming/winemaking risks and made the first steps.

Just to give a perspective on prevailing farming and winemaking methods in France post Second World War. Prior to the war, growing grapes and making wine was part of a wider polycultural artisan activity. After the war, many vineyards were untended, people started moving from the countryside to the city. Agriculture, for efficiency’s sake, was mechanised and, in effect, industrialised and monocultural. Quick chemical solutions were readily available. Artificial fertilisers, systemic fungicides, pesticides, herbicides, a battery of quick-fix palliatives could be easily obtained. These intensive interventions became the norm and contributed to the destruction of microbial life in the soils, serving to weaken the resistance of vines to disease, whilst simultaneously damaging the wider environment. Even to this day, when visiting wine regions, you will still witness some blasted landscapes and wonder how anything living can materialise from the places of sterility.

Wine schools, meanwhile, were teaching technical winemaking using cultured yeasts and numerous other adjunctives. Organic farming (let alone natural winemaking) was not something that got talked about nor even considered feasible. In fact, the AB classification (Agriculture Biologique) wasn’t instituted until 1985.

So, we come to Jules Chauvet, who has been called the godfather of natural wine by aficionados and naysayers alike. We can get hung up on terminology, and although he never used that term himself as far as we know, his influence is hugely significant.

A scion of Beaujolais, Chauvet was born in 1907 to a family who had been cultivating vines in the region for generations. His wine philosophy arose out of a love of nature and respect for authenticity and purity, and his approach was rigorously scientific as he sought to investigate how this notion of “naturalness” in wines might be efficaciously achieved. It is important to note that Chauvet was a winemaker and negociant with an appreciation of the history and culture of his region as well as a scientist (he studied at the school of chemistry in Lyon), and also was a writer and acknowledged expert taster, having trained with parfumiers in Grasse. He was effectively approaching the problem from all angles.

In the late 1940s Chauvet was running a negociant business, buying grapes from local farmers. He began to question the use of chemicals in viticulture and how their application might be damaging vineyards and the grapes and, as a consequence, militating against the expression of terroir.

He focused on various aspects of farming and winemaking in his research:

- Carbonic maceration. Chauvet conducted extensive research on carbonic maceration, a technique commonly used in Beaujolais. His work helped winemakers understand and refine this process.

- Stable fermentation without sulphur dioxide.At a time when sulphur dioxide was used liberally in winemaking, Chauvet developed techniques for fermenting wine without added SO2. This was a radical idea that laid the groundwork for today’s natural wine movement.

- Rejection of chaptalization.Chauvet was against the practice of adding sugar to increase the alcohol content, seeing it as an artificial manipulation of the wine.

- Native yeast fermentation.He encouraged the use of native yeasts for fermentation, believing they contributed to the wine’s sense of place.

- Chauvet’s studies on the microbiology of wine fermentation provided valuable insights into the role of native yeasts and bacteria in winemaking.

- Respect for terroir. Chauvet believed that wine should be an expression of its place of origin. He advocated practices that allowed the characteristics of the vineyard to shine through in the finished wine.

Chauvet’s became mentor to Morgon’s Marcel Lapierre in 1981 (Marcel having taken over the family domaine in 1973) as well as his friend, Jacques Néauport. This small group, quickly augmented by other growers, explored Chauvet’s ideas and began to put them into practice.

A particular taste paradigm informed the decision to make wine more naturally. Lapierre himself wanted to rediscover the original taste of Beaujolais, the type of wines his forebears might have been making and drinking fifty years ago, rather than the modern de-natured and frankly highly-sulphured interpretations of Beaujolais. The aim was to produce fresh, drinkable, nourishing wines with integrity, without additives.

Some of the greatest producers in France would cite Chauvet and Lapierre and the methods of likeminded producers in Beaujolais as inspirations for their vinicultural approach. And one may say that without the first wave of Beaujolais producers, the growth of natural wine as a whole would have been considerably slower.

Credit also must be given to Kermit Lynch, an American importer and writer, who coined the phrase “The Gang of Four,” a reference to a group comprising Marcel Lapierre, Jean Foillard, Guy Breton and Jean-Paul Thevenet, who were sharing ideas and working to a similar agenda. There were more than four, but the sobriquet stuck, and it became a great marketing term!

Lynch helped to promulgate the work of these vignerons and their fellow-travellers, in particular, and the reputation of Beaujolais, in general. Each region, of course, needs its heroes and flag-bearers. Just as one swallow (of Gamay) does not make a summer, it may be simplistic, at first glance, to view the fortunes of an entire appellation as resting on the shoulders of a tiny few, yet equally one cannot deny that the calibre of the work of such producers was instrumental in transforming the critical perception of an area that had hitherto become synonymous with nouveau wines and traditional brasserie liquid fodder.

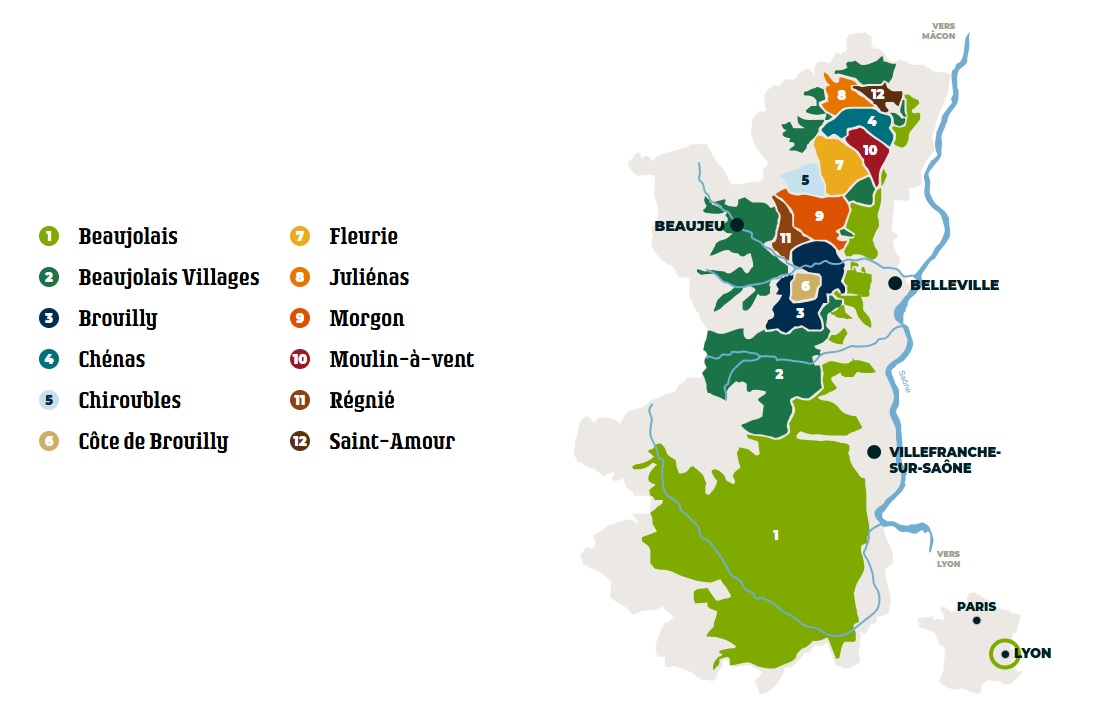

In terms of the evolution of the popularity of Beaujolais and the coinciding upsurge in interest in natural wine, the next significant period arguably took place around the recession of 2008-2010, a time of economic turbulence for the wine trade, when sommeliers and wine buyers started to cast around for wines that over-delivered on quality for the price. In short, alternatives to Burgundy (in particular) which was pricing itself out of the reach of many consumers. Evidence for this increase in interest in quality Beaujolais is anecdotal, but personal experience of selling Beaujolais at the time, suggests to me that there were multiple engaging factors. The cru system of Beaujolais could be “sold” as analogous to that of Burgundy, with the wines presenting an attractive value-alternative to those of its northern neighbour. Morgon and Fleurie had strong name-recognition already and were must-haves on every wine list. Perhaps there was less snobbery about Beaujolais, precisely because the cru system implied higher quality wines.

Concurrently, interest in natural wines was exploding with the growth of wine fairs (bringing together producers from different regions), and a pulsing bar scene in Paris which was attracting interest all over the world. A new generation of drinkers not beholden to the old certainties nor caring about received wine wisdom were spending money on unpretentious wines that they felt like drinking. In this counter-cultural, the so-called noble varieties were a matter of opinion, rather than written in stone and with these younger consumers seeking fun wines unencumbered by new oak and extractive winemaking techniques, characterised instead by easy fruit and clean flavours, the wheel turned sharply, and Gamay became somewhat the flavour of the day.

Yes, Gamay was trendy! Beaujolais wines generically became a fixture in wine bars (and natural wine bars). Moreover, the best examples found their way onto the wine lists of Michelin-starred restaurants. Suffice to say that as more quality-driven winemakers emerge from a region and discover commercial and critical success, it helps pour l’encourager les autres. As so many notable producers were working in a low-intervention manner, this would certainly have a “positive” knock-on effect on the practices of others.

Although the region as a whole has not had a proportionately high number of organically certified producers in the past, many have worked according to the precepts of HVE (“Haute Valeur Environnementale”) and Terra Vitis. This is a start. The number of organic producers has climbed dramatically and purportedly exceeds 300 (citation needed, as Wikipedia would say) or 15% of all producers. This has risen from a mere 5% a few years ago and would suggest that what was set into motion by a tiny handful of vignerons in the early-mid 80s has now blossomed (for various reasons) into something meaningful, a powerful momentum, if not a specific movement. If this progress to organic conversion continues at this pace for another decade, one might surmise that at least 30% of producers in the appellation would be certified organic, or in conversion.

Meanwhile, Raisin Digital, an app that has its finger on the pulse of the worldwide natural wine scene, lists no fewer than 111 practising natural producers in Beaujolais – 60 more than Bordeaux and even more than Burgundy. This is way more than a quorum. Without wishing to make comparisons between producers within the region, even a dispassionate observer might admit that the natural Beaujolais vignerons listed in the app are very highly regarded in the trade, with wines featuring on top lists.

Now to define the term “natural wine”. This is a rabbit hole to the centre of the earth and, as panellists, we didn’t have time to get down and dirty with this topic, although Sean made an excellent fist of trying to “undefine” it.

The term “natural” is emotive for some, provocative to others, but, quite simply, indicates a positive no-chemical approach to farming and winemaking. Absolute definitions are not particularly useful here. Those who seek to codify natural wines and protect the term from being abused are imposing precise definitions on living wines and prescribing actions on producers who surely need to make up their own mind on how best to make a wine every year. Applying appellation-style designations is all very well, but you have to make allowance. The caricature of natural winemaking as laissez-faire meets lazy-fare is the opposite of the truth. To make natural wine, you must be vigilant and accompany the process.

Wine is the product of cultured vineyards and the transformative process of winemaking. How the final wine comes to be is the question. Here there are myriad choices which distinguish a naturally made wine from a conventional one. A natural vigneron will focus on farming, because without healthy grapes unassisted fermentation will be much more difficult. Farming is more than one vintage in isolation. It involves creating the preconditions for healthy vines by nurturing healthy soils; it requires an understanding the climate and the vagaries of weather. In short, it is the evolution of a holistic approach that applies the best of organic, biodynamic and regenerative practices (i.e., those most appropriate to the vineyard). Conversely, the more a vineyard is treated with chemicals, the more the vines gain a kind of drug dependency.

The main tenet of natural winemaking is the preference for native ferment. The idea behind this is that indigenous yeast populations (found in the soils, the vineyards, carried in on the grapes, and present in the winery itself) work, in form of creative tension, in each vintage to make a singular wine. Other factors that may determine how the wine turns out will include the nature and composition of the vessel in which it is fermented, the ambient temperature of cellar, the temperature of the fermentation itself and several winemaking decisions on destemming, settling, racking and so forth. Natural is not hands-off winemaking – unless the wine tells you that you can take a step back. No vigneron wants their wine to be spoiled by careless (in)actions. Given that conventional wine allows many dozens of additions to the must, adjustments and corrections, copious manipulations only serve to denature the wine (some more than others).

Sean argued that the term natural wine was now redundant, that people don’t talk about it, that it was an artificial term that was effectively meaningless. It was a dead term, pushing up the daisies, it had ceased to be. Anne pointed out quite reasonably that Sean had found a clear definition for natural wine on his site. She made a compelling case for the linkage between natural wine producers and the increasing quality of Beaujolais wines. It could be argued that those who intervene less on the chemical front, are more intuitive winemakers. They are not using a one-size-all-recipe, but taste throughout the process and adjust, as necessary.

The death of natural wine has been solemnly announced by certain wine commentators since 2011, when the infant movement was in its cradle rather than crawling to the grave. As a freshly minted phenomenon then, it undoubtedly excited a huge amount of debate and no little controversy, but now the growers and their wines are entrenched, wine bars & restaurants, importers and retailers make their living from selling natural wine without fear or favour, we discuss these matters far less – and even the controversy around the subject seems more than a touch manufactured and histrionic. Journalists and bloggers have tended to describe natural wine as if it were a structured movement, ascribing a single overarching motivation or agenda to embrace the work of hundreds and even thousands of vignerons. Some vignerons, of course, may strongly identify as “natural” and be happy to be called such; others will disdain the term (after all, who wants to be codified or thought to be following fashion?) – and yet work in almost identical idiom. If it suits us to call them natural, then we will continue to do so as the spirit of the wines themselves and the endeavours behind them are what matters.

The implication of the epithet natural, which causes some to bridle, is that conventional wine is the antithesis of what real (my italics) wine should be. Not at all. It is not a moral judgement on two different types of wines.

Nor does it mean that natural wine is “wine made by nature alone”. Whatever that entails. It goes without saying that nature is an integral part of the process and that working in harmony with nature is a precondition of natural winemaking. As well as farming with minimal (or zero) chemical intervention, natural means that the transformation of grape juice into wine is carried with the minimal denaturation. Ophélie Dutraive and Anaïs Pertuizet, the two producers present at the debate, reinforced this point; both desired to make the best wine (and a wine they felt proud of) with the least intervention possible. They also communicated the pleasure they derived by working outside in the vines. It would seem wholly counter-intuitive to have this visceral attachment to your vineyard, farm diligently throughout the year, and then entirely change the nature of the wine by means of chemical superimpositions.

—

One question posed to the panel to ponder on prior to the talk was: “Do you see a relationship between the rise in the quality of Beaujolais wines, the premiumization of the region, and the emergence of natural wines in the region?”

Although rooted within the wider region, and the villages wherein they work, a vigneron is not merely a Beaujolais vigneron, but can also be a sensitive, creative and thinking person with a world view. The wine world thrives on exchange (of ideas). Young vignerons attend wine schools, then travel, do stages in other countries or regions, drink wine, talk about wine and constantly imagine and re-imagine how they might make their own wine. Growers in Beaujolais naturally influence each other, influence others outside their region, and are themselves influenced. Consider also how winemakers pour their energies into their wines. Being farmers rather than oenologists, they would surely want to showcase the work they have put into nurturing their vines over the year. Of course, you can use an array of technological equipment to make wine, but the human touch is what makes wine unique. Premiumization, in this case, if we choose to call it thus, is the collective effect of individuals making great “personal” wines, thereby raising the reputation of the region as a whole.

A second question for the panel was the following: “There is sometimes a somewhat caricatured schism between natural wines and non-natural wines. Does Beaujolais open new perspectives from this point of view? We note, for example, that the winegrowers associated with natural wines in Beaujolais are almost all AOC and not Vin de France. Doesn’t the region show us a more fluid continuum in styles and approaches?”

Natural wine vignerons recognise that the expression of terroir (which was Chauvet’s original objective) is more important than agonising about the precise quantity of sulphites that may be used during winemaking. Where acknowledgement of terroir specificity exists, there are the preconditions for a sophisticated cru system. Natural vignerons tend to talk about the soil, the aspect of the vineyards, the micro-climate and preserving what the grapes gather from their surroundings rather than talking technique. Technique is important, of course, but it is the means rather than the end, the way to preserve what the terroir provides.

If terroir is communicated through the cru system, then that is fine (and desirable). Having said that, growers may choose to make more experimental styles. The labels of these wines may be playful and make a virtue of the idea or feeling behind the wine rather than reference origin. These wines are often labelled Vin de France. Whether from a cru or a simple Beaujolais or Vin de France, quality is paramount, and the best wines show a mirror to what is possible with an amalgam of genius and hard work.

To address again a point made by my fellow-debaters, the so-called natural producers, the Gang of however-many, their descendants, and acolytes, represent a small (yet undoubtedly increasing) percentage of Beaujolais production, yet their quality-driven efforts have propelled the reputation of their region into the international mainstream. Yes, the natural wine scene is constantly changing, not just the parole of hipster wine bars now, but embedded everywhere that people drink wine seriously. It is not enough to make natural wines and assume they will be easily sold into a niche audience. To appeal to a wider audience, the wines have also to be good enough.

And the best natural Beaujolais wines are breaking through perceived price ceilings. That may be as a result of the exalted reputation of certain producers, and supply-and-demand, combined with meagre yields in certain vintages. If these higher prices help consumers perceive that the hand-crafted has greater intrinsic value than the mass-produced, then it is not a bad thing in itself, although undoubtedly we would prefer that wines are not priced on the basis of their reputation.

If we simply left brand Beaujolais to the supermarkets to popularise, the image of all wines from the region might be synonymous with the lowest common denominator – whether valid or not. Such was the impact of Beaujolais Nouveau on the wider perception of what Beaujolais wines were all about. Even the more dynamic and innovative producers and their terroir-driven wines would be lumped into the general category of “brand Beaujolais”. It is reductive to try to explain wine with simplistic branding and slogans, much to advertise the diverse range of growers, winemaking choices and wines on offer and talk about quality. There are ten current crus and a host of wines outside the cru system. Within certain crus there are different terroirs, different farming practices, and winemaking choices. Each wine is what it is. Each wine can exemplify Beaujolais or its cru in its own singular way. That is a nuanced view, but a positive message to convey, and those that work with the wines (importers, retailers and wine buyers) should help to educate their customers about this.

Sean said, (rightly) gesturing at a table where wines from various Beaujolais were available to taste prior to the debate, that wines represented on the night were the tip of the iceberg (as in not representative). Natasha, with her statistical overview of Beaujolais production, made the same point.

Without wishing to sound over-proverbial, the tip of the iceberg is the visible part of the iceberg. And this iceberg is rising further into view. Most wine regions have a perceived hierarchy of quality whether as part of a cru system or a critically reputational one. Those growers who are the outliers, the risk takers, and who have a clear vision for their wines may well be in the statistical minority, but their efforts (and successes) will always cause a ripple effect. In Beaujolais, as we have noted there are 111 (and counting) producers working in the low-intervention idiom, primarily in the defence of appellation, but also to help make wines that are more fluid, more lovely, and truer to their terroir. (Of course, there are exceptions and individuals make wines according to their nature.)

Organic farming, natural winemaking are not just trendy labels to adhere to. The idea of working with respect for the land and not putting chemicals into wine is not a new idea. Two generations ago, wine was made for personal consumption. It was called wine. Ever since wine became a commercial product for all, the human requirement to put things into boxes, define them and rate them and rank them, created the need for an appellation system, designed originally to impose minimum standards and defend quality, and to assist as a driver in the marketing of a region. Those who market the region may want to convey a story that can be easily digested by an audience. The truth is always more layered. An understanding of the natural wine dynamic is critical, however, to understanding the fortunes of the region and the path that many younger producers have chosen to pursue post Chauvet and the so-called Gang of Four.

On reflection, the question up for debate, never offered a binary choice in the classic sense of one side is right and the other wrong. My point is that one cannot disavow history and culture even if outcomes are serendipitous rather than planned. You can certainly say that statistically a natural wine trend looks insignificant in the context of the production of millions of bottles of conventional wine. Alternatively, you can assert that the region’s reputation was enhanced by a few growers, that overall there is a perceptible change in farming and winemaking practice, that the rise in organic farming and low-intervention winemaking in the region is exponential, with the added caveat there is still a way to go. You can argue that the premise of the question is wrong in attributing change to natural winemakers when the idea of natural winemaking is a questionable one and so hedged with relative definitions as to be meaningless. Semantics aside, I think we can say that natural wine is a thing, a reasonable way of describing the practice and the spirit of vignerons and their wines. The influence of these natural wine producers on farming and winemaking methods within Beaujolais (not to mention outside) is clear. It is surely equally undeniable that the high profiles of such growers have helped to change the perception of Beaujolais over time into that of a quality wine-producing region.

Thanks to Sowine for organising this debate, to Queena for moderating it so ably, and to my fellow panellists for their brilliant and articulate presentations both for and against the motion.