The process of fermentation in winemaking turns the must (grape juice) into an alcoholic drink called wine. During primary fermentation, yeasts transform sugars present in the juice into ethanol and carbon dioxide. The most common yeast associated with winemaking is Saccharaomyces cerevisiae which is favoured due to its predictable and vigorous fermentation capabilities, tolerance of relatively high levels of alcohol and sulphur dioxide as well as its ability to thrive in normal wine pH (between 2.8 and 4). Despite its widespread use which often includes deliberate inoculation from cultured stock, S. cerevisiae is rarely the only yeast species involved in a fermentation. Grapes brought in from harvest are usually teeming with a variety of “wild yeast”. These yeasts often begin the fermentation process almost as soon as the grapes are picked when the weight of the clusters in the harvest bins begin to crush the grapes, releasing the sugar-rich must.

Other ambient yeasts that live in the winery itself may be involved in the fermentation process.

Natural wines are made with wild or ambient yeasts.

The nature of fermentation is determined by temperature and speed as well as the levels of oxygen present in the must at the start of the fermentation (oxygen is useful for certain yeasts). Fermentation may be done in stainless steel tanks, which is common with many white wines, in an open wooden vat, inside wine barrels and inside the bottle (during secondary fermentation, for example).

Fermentations may temperature controlled (using thermos-regulated tanks), running cool water through pipes, or having a winery with air-conditioning. The structure and composition of the cellar itself will have an effect on the nature of the ferment.

Fermentation can be halted by means of reducing the temperature of the must or by the addition of grape brandy (fortification).

Fermentations may also stop when the yeasts are unable to complete the task of consuming the sugars in the wine (usually as a result of nitrogen-deficient musts). Using a culture yeast strain or adding nitrogen to the must are ways of resolving stuck ferments.

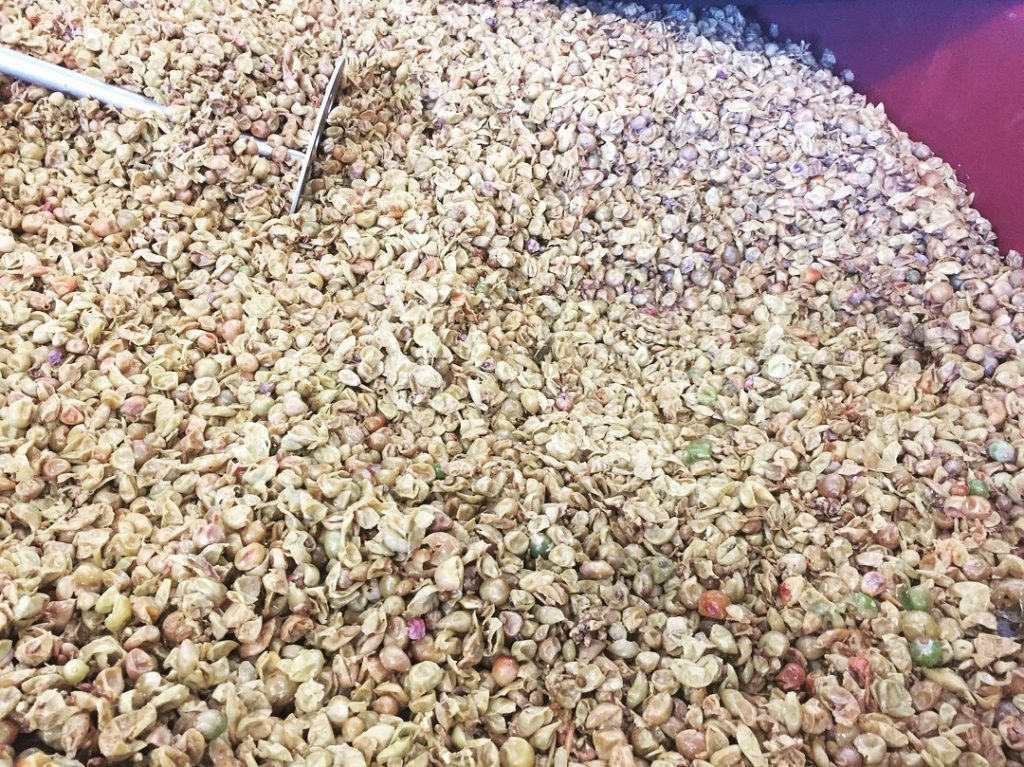

As well as the primary fermentation, other forms of fermentation include carbonic maceration (whole clusters of grapes being stored in a closed container with the oxygen in the container being replaced with carbon dioxide). Unlike normal fermentation where yeast converts sugar into alcohol, carbonic maceration works by enzymes within the grape breaking down the cellular matter to form ethanol and other chemical properties. The resulting wines are typically soft and fruit.

Malolactic fermentation is a secondary fermentation, where malic acid, naturally present in grape must, is converted by bacterial reaction into mellower lactic acid. Most natural wines undergo the secondary malolactic fermentation.